As narrated by the classical author Ovid, Atalanta agreed to marry the man who could beat her in a race. Using a ruse Hippomenes dropped three golden apples, received from the goddess Venus, shown in her chariot at top left. Atalanta could not resist picking them up and thus lost the race. Although the story warns against greed for gold and sensual temptation, de Vos imbued his depiction with sensory appeal by adopting an expressive drawing technique that captures the wild race and entices the senses of the viewer.

Maarten de Vos (Antwerp 1532-1603) Atalanta’s Race around 1585 Pen and brown ink and wash with white highlights, on brown laid paper; traces of black chalk or charcoal 203x320mm Samuel Courtauld Trust: Witt Bequest, D.1952.RW.98

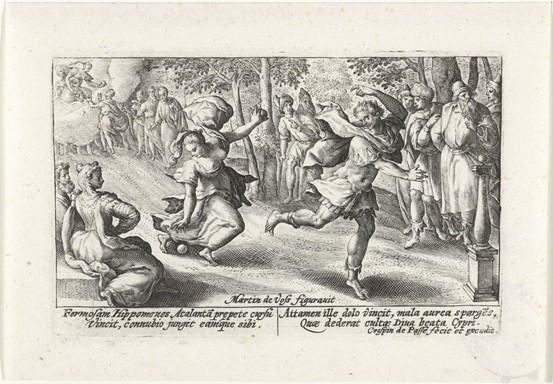

According to the myth of Atalanta’s Race, popularized by the Roman poet Ovid and depicted here by the Netherlandish artist Maarten de Vos, Atalanta would marry any man who beat her in a race, but those who lost would be killed. At the center of the drawing we see two figures in classical dress racing across the picture plane. The male figure leads, reaching for the post indicating the finishing line, while the female figure follows behind, distracted by the golden apple on the ground. Their fast movement is made apparent by the windswept drapery and the instability of their stance. In the background of the drawing, roughly sketched crowds of figures watch, whilst at the bottom left of the drawing are two figures – one female seated, her back to the viewer and a male, bearded character, leaning towards the race – eagerly observing the outcome. At the top left Venus is depicted in her swan-drawn chariot handing golden apples to Hippomenes. Hippomenes dropped these golden apples, which Atalanta could not resist picking up; he thereby won the race and the right to marry her.

In 1602, the Netherlandish printmaker Crispijn de Passe engraved this subject as part of a series of seven prints which treat stories from Ovid’s Metamorphoses as ‘moral lessons’ warning against greed and the pursuit of gold.[1] As Ilja Veldman notes, these engravings were made with the intention of teaching young people to ‘be on their guard when entering the arena of love’.[2] In giving new identities to the gods and heroes of antiquity, artists adapted myths in order to reflect various moral concerns of the day.[3]

Crispijn de Passe after Maarten de Vos, Atalanta en Hippomenes Engraving 81x128 mm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

De Passe’s engraving was not made directly from the Courtauld drawing but rather from a looser, intermediary drawing roughly the same size as the print and now at Winsor Castle.[4] The Courtauld drawing, among the more finished in De Vos’s oevure, seems to be a finished work possibly intended for presentation. Its moral message can be read not only in its subject, the myth of Atalanta but also in its composition and the way in which the figures are drawn. According to Joseph Manca, artists often used weight and stability in their figures to convey a sense of goodness or virtue, weakness of stance connoting moral failing.[5] In Atalanta’s Race the figures of Hippomenes and those watching the race are depicted with shadows which give them physical as well as moral weight, or gravitas. In contrast, the figure of Atalanta appears ungrounded as she greedily reaches for the apples, with no feet on the ground, unstable both physically and morally. The moral weight of the message is also conveyed in the gravity of the composition, the weighted pillar to the left and the figures to the right create a firm pictorial foundation.

De Vos’s expressive and seemingly free style adds to the sensory appeal of the drawing, yet a closer examination reveals a faint black line, most likely a preliminary under-drawing, which undermines the sketchy and spontaneous appearance that de Vos strove to manufacture. While De Vos presents a moralising theme and message that warn against greed for gold as well as sensual temptation, by rendering Atalanta’s breasts exposed and by adopting this voluptuous and expressive drawing style, he also creates a drawing that will appeal to the senses of the viewer.

Like many early modern artists, de Vos employed mythology in order to give moral purpose to his designs that delight the senses.[6] At a time of great change and unrest in the city of Antwerp, Maarten de Vos was the epitome of a ‘modern’ artist, able to adapt his style and apparent political and religious perspective for many different patrons. Textual inscriptions added to the prints after his designs frequently clarified or imposed a moral gloss on his singular treatment of myths. Combining word and image, these engravings fused De Vos’s expressive style with an explicitly didactic message, enhancing his international fame as a designer of sophisticated, moralizing prints.

MR

Footnotes

[1] Schuckman 1995, nos. 1568-1574, each with four lines of Latin text by Willem Salsman. Atalanta’s Race is the penultimate print in that series; Ibid., no. 1573.

[4] Drawing at Windsor Castle, Coll. of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, inv. 14965; see White and Crawley 1994, no. 204.

Bibliography

FINDLEN 1990

Paula Findlen, ‘Jokes of Nature and Jokes of Knowledge: The Playfulness of Scientific Discourse in Early Modern Europe’ Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 43, 1990, 292-331.

MANCA 2001

Joseph Manca, ‘Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning’ Artibus et Historiae, vol. 22, 2001, pp. 51-76

SCHUCKMAN 1995

Christiaan Schuckman, Hollstein’s Dutch & Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Wodocuts 1450-1700, vol. XLV, Maarten de Vos, D. De Hoop Scheffer (ed.), 3 vols., Rotterdam 1995.

SEZNEC 1953

Jean Seznec, The Survival of the Pagan Gods: The Mythological Tradition and its Place in Renaissance Humanism and Art, Chichester, 1953.

VELDMAN 2001

Ilja Veldman, ‘Amorous Escapades with Ovid: the Metamorphoses (1602-04)’ in Yvonne Bleyerveld (ed.), Profit and Pleasure Print Books by Crispijn de Passe, Rotterdam, 2001, 73-84.