My contribution to the Courtauld’s symposium draws on a longstanding research project at Pickering Church (North Yorkshire). I am an historic buildings expert, not a wall painting specialist, but the provocation for what has become a twenty year relationship with the church and its community is a quotation from the great art historian, Sir Nicholas Pevsner. On the one hand, Pevsner highlights the significance of the paintings as one of the most ‘complete’ schemes in the country, offering visitors a powerful experience of the medieval ‘painted church’. He is keen to point out, however that the paintings were ruthlessly restored by the Victorians, but as they ‘were never great art’, it is probably better to see them in their current state clearly than their original brushwork dimly!

As an archaeologist, I am not, perhaps, as concerned with the aesthetics or the authenticity of wall paintings like Pickering as Pevsner. Rather, my interest lies in the intersection of people and buildings and in the methods by which we can reconstruct the story behind the discovery, restoration and conservation of the scheme. And whilst Pickering may be exceptional in the range of sources that survive to illuminate its story, it is not unique. By piecing together a range of published and unpublished primary sources we get an insight, not only into the emergence of art historical studies of medieval wall paintings but also the practices of conservators and other experts in documenting, reporting and reflecting on their methods – something which a number of speakers at the symposium have highlighted is often a gap in surviving records of care – and which the digitisation of the archive will make a powerful contribution to correcting for future generations.

Discovery

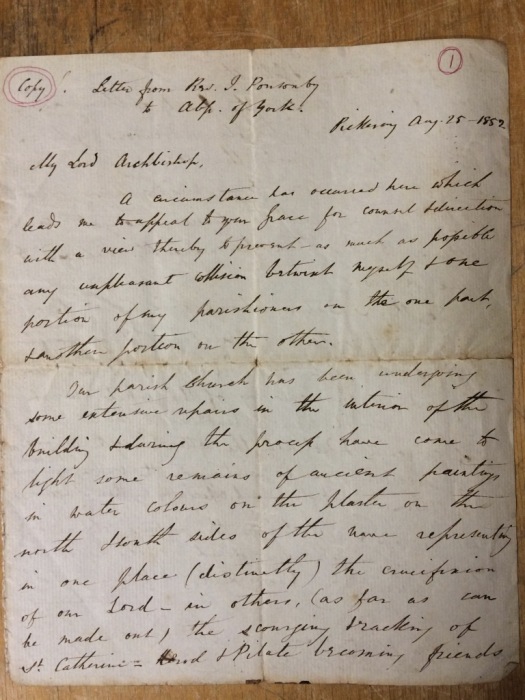

My first reflection would be that we do not always know what survives within parish archives. Pickering still maintains an important vestry archive which includes a remarkable exchange of correspondence about the re-discovery of the paintings in August 1852, between the Revd John Ponsonby and the Archbishop of York, Thomas Musgrave. In it we see the clash of an elderly, conservative clergyman horrified by the appearance of Catholic saints striding across the walls of his church, and the antiquarian interests of his Archbishop, who happened to be President of the York Architectural Society.

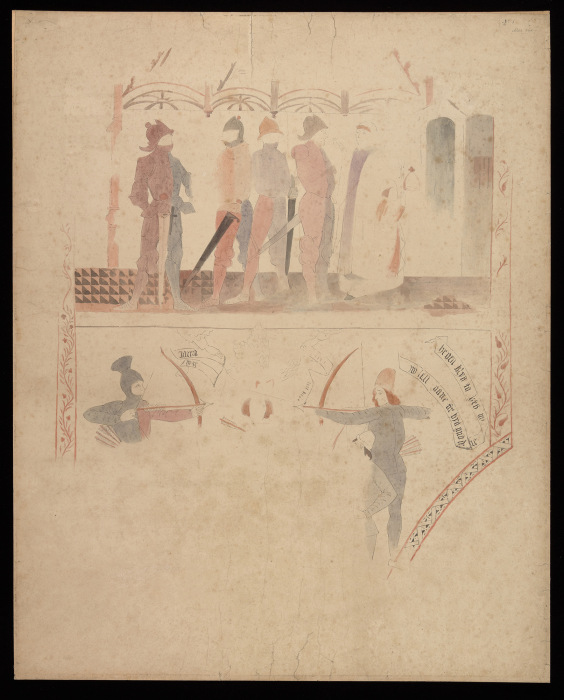

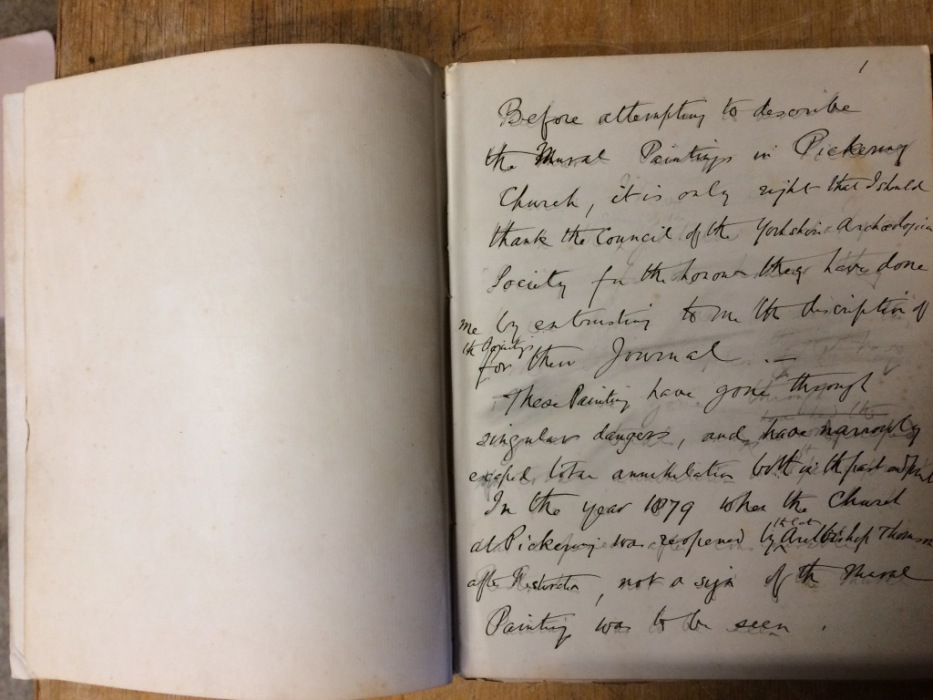

From the Society’s contribution to the Associated Architectural Societies Reports and Papers for 1853, we have a minutely detailed description – and contemporary interpretation of the scheme – originally accompanied by watercolour drawings made by their artist, Mr Bevan. And although these were subsequently lost, we can substitute a series of surviving drawings made by the Scarborough Archaeological Society’s artist, Tom Chambers, for a similar lecture to their society.

Through newspaper articles we can see excitement spreading, as the Archaeological Institute dispatch Mr Spencer Hall, Librarian of the Athenaeum Club, to report on the papers, and local celebrity artists such as Mr Frank Howard write opinion pieces about their national importance and potential to put Pickering on the map.

But these sources also give us an insight into tensions on the ground. Revd Ponsonby is not a popular figure in the town, as the anonymous grumblings of the correspondent ‘Rusticus’ makes clear. He is living a comfortable life, with a secure income, house and curate, but refuses to support local educational initiatives, such as the founding of a Mechanics Institute. And as the antiquarians descend upon the church, they are warned that he has ‘form’ in the ‘wanton’ destruction of other paintings that have evidently come to light in earlier building works. Although his letters suggest his parishioners are divided in their opinion of the paintings, the views of his solicitor and wine merchant churchwardens are clear – the paintings are good for business, even if Ponsonby refuses to preach while they are exposed to view. They also illuminate Ponsonby’s wider concerns about the ‘dangerous days’ being faced by the Anglican Church in 1852: the internal threat he perceived being posed by the Oxford or Tractarian movement to reformed religion; the resurgence of Catholicism in the wake of the ‘Papal Aggression’ of 1850, including the appointment of a new Bishop of Beverley and the establishment of a new Catholic seminary at nearby Ampleforth. Non-Conformism, too, was on the rise in Pickering with new Methodist Chapels under construction.

Ultimately, Ponsonby defies his archbishop, instructing a local builder, Mr Salton, to plaster over the paintings using a ‘copperas’ mix. The survival of a notebook in the vestry archive, which contains a draft of an article published in the Yorkshire Archaeological Journal (YAJ)in 1895 on the restoration of the paintings by a later incumbent, Revd George Herbert Lightfoot, contains beautiful detail (not included in the published account) that the builder sought to change the recipe to minimise the damage to the scheme.

Restoration

Between 1852 and 1880 there are other stories to be told – not least of the scandalous affair between Ponsonby’s successor, the Revd George Cockburn and a 26-year-old parishioner, Jane Wardell researched by my former tutor at York, Professor Ted Royle as a Borthwick Pamphlet, A Church Scandal in Victorian Pickering (2010). It is a fascinating example of how local history detective work can tell a nationally-significant story about gender and class relations. I recommend it!

The scandal left Pickering Church empty, and the next chapter in the story of Pickering is the story of the restoration of both the church building and its community, followed by the re-uncovering and re-painting of the scheme by the Revd George Herbert Lightfoot in the 1880s. Here, a range of sources survive, from Faculty petitions, plans and drawings, churchwardens’ accounts and Church Commissioners archives deposited in local and national archives, newspaper accounts and, for the first time, photographs and postcards as well as Lightfoot’s contributions to local antiquarian society visits, publications including his YAJ article and guidebooks. Together, they provide a fascinating insight into both the attitudes and methods of Lightfoot and his artistic advisor, Edward Holmes Jewitt of Shrigley & Hunt (Lancs.), one of the leading ecclesiastical art firms of the day.

Pevsner might deem this a ‘ruthless restoration’, but Lightfoot provides an aesthetic and theological justification for wanting to provide his parishioners and visitors with a ‘complete’ and legible scheme through which they could understand the purpose of the paintings and their rehabilitation into a late nineteenth-century century form of religious practice. Comparing the surviving drawings and descriptions allow us to see that Lightfoot and Jewitt did a little more than ‘fill in the outlines’ which had survived Ponsonby’s iconoclasm, drawing on the earlier antiquarian descriptions and drawings but also presumably other examples of fifteenth-century paintings coming to light in churches across the country listed in new sources such as Charles Keyser’s catalogue of paintings. Indeed, subsequent editions of the list reveal the gradual restoration of the scheme over the course of a decade.

The account gives little detail of the materials and methods used by Jewitt, and any attempts to triangulate this with the accounts of Shrigley & Hunt are frustrated by the destruction of most of their company archives in a fire. However, another account book (recovered this time from a store behind the organ in the church) reveals the paintings had to be cleaned in 1902, suggesting that the coatings used to ‘preserve’ the newly painted scheme in the 1880s had created problems only twenty years later, in the very year that Lightfoot died.

Contemporary newspaper and journal accounts from the Yorkshire Architectural Society and Archaeological Institute’s summer excursions in the 1890s also reveal the very different perceptions of the ‘success’ of Lightfoot’s restoration, which can be set against the context of new conservation philosophies emerging from the work of Ruskin, Morris, and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (S.P.A.B.), in the wake of the loss and destruction of ecclesiastical art and architecture in the later part of the nineteenth century. Once again, Pickering provides a lens through which we can understand contemporary debate and the emergence of approaches which continue to influence conservation practice today.

Twentieth-century conservation work

As we move into the twentieth century, a range of sources can be used to study the cycle of conservation interventions in the church at Pickering, every twenty years or so. In 1915, whilst still a student, Ernest William Tristram came to Pickering, drew the paintings and incorporated them into the 1923 landmark Royal Academy exhibition and catalogue, The British Primitives. Ten years later, however, Pickering was not included in Leeds City Art Gallery’s Exhibition of Tristram’s paintings – much to the disappointment of the Yorkshire press. By then, perhaps, Tristram understood the paintings to be more a product of Victorian restoration than medieval artistic production. But he advised and oversaw their cleaning and re-waxing between 1930-36, as he did so many schemes across the country, often with disastrous results for their preservation.

Pickering’s documentation in this period consists of further letters from the incumbent, the Revd Arthur Bundle, seeking funding from the Pilgrim Trust to undertake the work, and attempting to engage the local community in this further conservation work – although the publication of Ponsonby’s correspondence with the Archbishop as part of this history sometimes led to confusion, as an exchange in the street, published in the church’s parish magazine, attests!

The harsh winter of 1947, as well as the impacts of Tristram’s wax treatment of the paintings, led in 1951/2 to a further phase of cleaning and re-painting, this time by Tristram’s successor, Clive E. Rouse. A set of remarkable scale drawings of the paintings made at this time by Janet Lenton, mostly on wall paper, still survive in the church’s old safety deposit box, now in a Solicitor’s office in Pickering. Rouse deployed a new treatment – silicaseal – on the paintings, which was not successful. Just over a decade later he returned, as did Eve Baker, to advise the parish and the Pilgrim Trust’s wall paintings committee on the best course of action. What is fascinating here is the measured consensus of both experts, advising against the more radical proposals of the committee to remove the Victorian over-painting to reveal the ‘authentic’ medieval scheme beneath. Very little, they suspected, would be left, and it was preferable to make the most of the scheme the parish had always known. One suspects that this view was also expressed forcefully to these visiting experts. Rouse’s repainting of the St. Christopher and Christ child figures should be understood in this light.

‘Now we see through a glass darkly’….

In writing the story of Pickering, I wanted to share something of the joy of the detective work involved in researching local and national archives, bringing together such a diverse range of sources to understand not only what happened to Pickering’s paintings, but also why. I suspect that behind many of the schemes of paintings surviving in our churches and cathedrals are equally fascinating insights into the microhistories of local communities, incumbents and national experts coming together to understand and preserve these paintings, and that the Courtauld’s new digitisation project will enable the clues compiled by David Park to be uncovered and to spark new research and storytelling by people helping to care for these schemes today, as it did for me.

But at the heart of the archive is also a treasure trove of comparative material that may help us find new ways of understanding the meaning of medieval wall paintings. The last sources I found for Pickering were the earliest, which shed light on the scheme’s creation – one surviving medieval will, referring to the guild of the Blessed Virgin, the only religious fraternity or ‘service’ we have information for, which survived until its goods were surrendered by Richard Judson, its priest, in 1548. Pickering seems to me to be a design by committee and unpeeling its layers reveals one final hidden meaning which I have tried to make sense of in the final chapter of my recent book.1 This meaning opens up more critical enquiries about the late medieval wall paintings generally, which The Courtauld’s digitisation project will undoubtedly facilitate.

Conclusion

It has been a great privilege and pleasure to research the paintings of Pickering and to have fallen in love with the place and its current community, with whom I am currently working to plan the next chapter in the conservation of the scheme, together with conservation expert and faithful friend of the paintings, Tobit Curteis. The Courtauld’s archive was central to guiding my early research, as was the expertise and encouragement of Professor David Park. It is wonderful to see the archive now moving into the next phase of its life cycle – opening up new opportunities for scholars and the general public, too, to research, understand and help care for, our painted past.

1 Kate Giles, The Wall Paintings of Pickering Church: their discovery, restoration and meaning (Shaun Tyas, 2022), can be ordered directly from the publisher at pwatkins@pwatkinspublishing.fsnet.co.uk.