How has belatedness shaped the historiography of the arts of North America? How have projections of belatedness shaped the inclusion or exclusion of African American, Latinx, Caribbean, and Native American art in the canon of “American art,” as well as art from regions outside the Northeast? How have the arts of Canada and Mexico been framed in dialogue with the art of the United States? Has visual studies recentred these hierarchies? In the context of the United States, how has the discipline’s emergence in dialogue with the American Mind school of American studies continued to shape the sub-field’s relationships with the wider field and canons of the history of art? How have narratives of modernist progress in abstraction shaped critics’ constructions of belatedness around artists who retain figuration? How have artists operating outside geographic and cultural “centres” of art production taken up, mimicked, or inverted expectations of cultural belatedness?

Organised by Professor Emily C. Burns (Director of the Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West at the University of Oklahoma) and Professor David Peters Corbett (Professor of American Art and Director of the Centre for American Art, The Courtauld) as part of the ‘Belatedness and North American Art’ series.

Programme

Friday, June 16

12.45 pm – Registration (Reception)

1.15 pm – Welcome and Introductory Comments (Lecture Theatre 2)

1.30 pm – Session 1: Belatedness as Difference

From New Spain to Mexico, Belatedness as a Tool of Empire

Emmanuel Ortega

Always Late to the Party: North American Art, Science, and Epistemological Anxiety in the Twentieth Century

Alexis L. Boylan

2.45 pm – Coffee Break (Research Forum Seminar Room)

3.15 pm – Session 2: Belatedness as Positionality (Lecture Theatre 2)

Tipi and Dome: Indigenous Futurism at Expo 70

Jessica L. Horton

Between the United States, Britain and the Caribbean: A historiography of belatedness

Leon Wainwright

4.30 pm – Reception, all welcome (Research Forum Seminar Room)

————————-

Saturday June 17

10.00am – Registration (Reception)

10.30am – Welcome and Introductory comments (Lecture Theatre 2)

10.45am – Session 4: Belated Inclusions

When did Indigenous art become “American”?

Elizabeth Hutchinson

American Art Historiography, Slavery, and its Aftermath

Tanya Sheehan

12.00pm – Lunch (provided for speakers and organisers)

1.30 pm – Session 3: Belatedness and American Art Histories

The Late Jacob Lawrence

Juliet Sperling

Belatedness, Near and Far

Martha Langford

Yet-to-be-dismantled”: Elizabeth Bishop and Winslow Homer in 1974

Nicholas Robbins

3.15 pm – Concluding Remarks

3.30 pm – Close of Conference

From New Spain to Mexico, Belatedness as a Tool of Empire

Emmanuel Ortega, Marilynn Thoma Scholar in Art of the Spanish Americas and Assistant Professor in the School of Art and Art History, University of Illinois at Chicago

This presentation will trace the ways in which painting practices of central Mexico have always co-opted European styles “belatedly” in the service of empire and nation building. Following a pattern of Novohispanic institutions’ two-hundred-year insistence on Mannerist painting, Romanticism thrived in Mexico well passed its European apogee in the late 1800s.

In his seminal book, Race and Manifest Destiny, Reginald Horseman asserts that the rise of Romanticism in the US “parallels in time the growth and acceptance of the new scientific racialism,” because it was “less interested in the features uniting mankind and nations than in the features separating them” (159). In Mexico, a similar racially driven attachment to Romanticism occurred towards the end of the nineteenth-century—actively opposing the neo-classic conventions previously used to articulate the image of the nation. Spawning from a period where the superiority of a mestizo race was in direct contestation to the “Indian predicament” (the highlighting of a glorious Meso-American past while mistreating native communities), the objectivity that anchored the nation’s history in painting was affixed to a Romantic current of landscape, sentimentally calling on to emotions of a “nascent race.” Both Mannerism and Romanticism, and coeval painting styles in between, show how in the visual culture of central Mexico, belatedness has been used as a hegemonic tool of expression.

Emmanuel Ortega is the Marilynn Thoma Scholar and Assistant Professor in Art of the Spanish Americas at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and a Scholar in Residence at the Newberry Library for 2022-2023. Ortega has lectured nationally and internationally on nineteenth-century Mexican landscape painting, and visual representations of the New Mexico Pueblo peoples in Novohispanic Franciscan martyr paintings. An essay titled, “The Sentimental Fantasy of Miscegenation: La Malinche in the Popular Mexican Imaginary,” was published by the Denver Art Museum in association with Yale University Press in March of 2022. His book project, Visualizing Franciscan Anxiety and the Distortion of Native Resistance: The Domesticating Mission is under contract with Routledge.

Always Late to the Party: North American Art, Science, and Epistemological Anxiety in the Twentieth Century

Alexis L. Boylan, Director of Academic Affairs, UConn Humanities Institute; and Professor, Art + Art History Department and Africana Studies Institute, University of Connecticut

Belatedness suggests schedules, progress, a notion that a delay will irrevocably set something behind, or that a distraction threatens to confuse momentum. While belatedness most certainly can be generative, it is often weaponized. Thus, in seeking meaning, authenticity, and authority, narratives emerge about what disciplines and fields can promise the most futurity, the most drive, the most distance from belatedness. All knowledge is not equal, and belatedness becomes the language of disciplinary anxiety about cultural and intellectual authority.

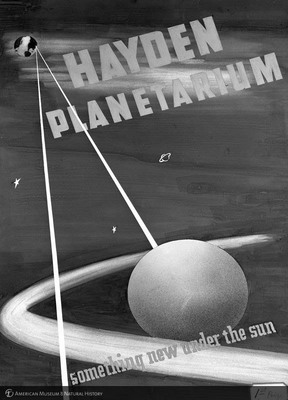

While antagonisms between the sciences and the arts (and humanities) are most typically framed as a divide between “two cultures,” this talk argues that the dialogues concerning belatedness create much of the cultural and epistemological tension between art and science in the twentieth century. These tensions are evidenced in the dialogues surrounding visualizing science at the American Natural History Museum (NYC). Focusing on the Hayden Planetarium and the Rose Center for Earth and Space, I show how these spaces manifested the fear of belatedness as a competition of intellectual and visual authenticities. These projects, which promise a potential to promote the dual potentials of art and science instead expose rivalries for epistemological dominance and highlight the ongoing power and problems of belatedness to our intellectual landscapes.

Alexis L. Boylan is the director of academic affairs of the University of Connecticut Humanities Institute (UCHI) and a professor with a joint appointment in the Art and Art History Department and the Africana Studies Institute. She is the author of Visual Culture (MIT Press, 2020), Ashcan Art, Whiteness, and the Unspectacular Man (Bloomsbury Academic, 2017), co-author of Furious Feminisms: Alternate Routes on Mad Max: Fury Road (University of Minnesota, 2020), editor of Thomas Kinkade, The Artist in the Mall (Duke University Press, 2011), and editor of Ellen Emmet Rand: Gender, Art, and Business (Bloomsbury Academic, 2020).

Tipi and Dome: Indigenous Futurism at Expo 70

Jessica L. Horton, Associate Professor of Art History, University of Delaware

At Expo 70 in Osaka, Japan, space-age pneumonic architecture and immersive multimedia environments heralded the “city of the future.” This utopic futurism, embedded in the Expo’s official theme, “Progress and Harmony for Mankind,” collided with a transnational apocalyptic imaginary shaped by wartime ruins and mounting ecocrises. Attended by a record-breaking 64 million visitors, the first Asian exposition is remembered simultaneously as the apotheosis and death knell of World Fairs. This talk is concerned with the alternative temporalities embedded in Indigenous North American architecture, a standard inclusion in World Fairs since the format emerged in Europe in the 18th century. Against the truism that such features were anachronisms displayed to enhance hegemonic narratives of progress, I consider how a six-meter-tall painted lodge in in the US Pavilion at Expo 70 modelled an Indigenous futurism premised on adaptive continuity, renewal, and reciprocity with a more-than-human cosmos. The Crow Tipi—named for its avian origins and designs—was created by Blackfeet artist Darryl Blackman on commission by the United States Information Agency and gifted to the city of Osaka. Reading the tipi as coeval with the dome, the quintessential architecture of the future c. 1970, opens up new avenues for thinking about World Fairs as relational systems beyond the dialectic of primitivism and progress that predominates in historiographies of North American art.

Jessica L. Horton is an associate professor of modern and contemporary Native North American art at the University of Delaware. Her first book, Art for an Undivided Earth: The American Indian Movement Generation (Duke University Press, 2017), traces the impact of Indigenous spatial struggles on artists working internationally since the 1970s. Her second book, Earth Diplomacy: Indigenous American Art and Reciprocity, 1953–1973 (forthcoming, Duke University Press) examines how artists revitalized longstanding Indigenous cultures of diplomacy in the unlikely shape of Cold War tours, translating Native political ecologies across two decades and five continents.

Between the United States, Britain and the Caribbean: A historiography of belatedness

Leon Wainwright, Professor of Art History, The Open University UK

In the late 1950s and early 60s, as the British Empire underwent decolonisation, artists in London faced northwest, looking across the Atlantic to the United States. Fascinated by the scale and tone of its industrialised, popular cultures – advertising, music, celebrity – artists paid tribute to the newfound global dominance of America, its ‘centrality’ and ‘advances’, its ‘lead’. But, in that show of transatlantic admiration, there was an opportunity to reassert an exclusive version of national identity in Britain. Pervasive, local anxieties about the diminishing status of Britain were channelled into the cultural field, which made a virtue of Britain’s growing provincialism and belatedness. There was embrace of ‘displaced’ or ‘outsider’ subjectivities, through the celebration of gay, working class and Jewish personalities. The persuasive power of such discourses of inclusion rested, however, on the significant edging out of Caribbean, African and Asian artists of the Commonwealth, and women.

We can explore a vivid register of the geopolitics of this period through the figure of Caribbean-born painter Frank Bowling (b.1934), who migrated multiple times across the Atlantic before settling in New York in the late 1960s. For many decades, Bowling’s work and biography were omitted from the record of British pop, as well as American art of the 1970s. Since those accounts have undergone revision of late, with Bowling being brought into the foreground in each national context, we may come to understand more fully the British, American and Caribbean scenes together: assessing the role of belatedness in the historiography of this period, and exposing discretely told art stories to one another.

Leon Wainwright is Professor Art History at The Open University. A recipient of the Philip Leverhulme Prize in the History of Art, his single-authored book titles are Timed Out: Art and the Transnational Caribbean (2011) and Phenomenal Difference: A Philosophy of Black British Art (2017). He has four edited books and, in addition, the latest volume in the successful series of anthologies Art in Theory: The West in the World (2021), co-edited together Paul Wood and Charles Harrison.

The Late Jacob Lawrence

Juliet Sperling, Assistant Professor of Art History and Kollar Endowed Chair in American Art, School of Art + Art History + Design, University of Washington

In 1978, Jacob Lawrence delivered a high-profile public lecture about his career. He began not with one of his celebrated multi-panel narratives of the 1940s and 50s but with an image of his newest work. “I thought I would start with the latest slide so you can see where I am in this moment,” he remarked as The Studio flashed onto the screen. In the small gouache, the artist ascends the stairs of his studio in Seattle, a city that he had called home since permanently leaving New York in 1971. Lawrence depicted his workspace just as it appeared then, with one exception: in his painting, the window looks out onto a 1943 Harlem street. The Studio is a self-portrait in two places—or times—at once.

This paper takes The Studio’s temporal and geographic collisions as an opening onto the undertheorized entanglements of periodization, canonicity, and identity in the historiography of American art. From the moment Lawrence swapped the New York City gallery scene for a west coast classroom, he became for scholars and critics an artist in his “late period”—even though the transition fell at his career’s mathematical midpoint. But as the painter’s keen manipulation of chronology in the lecture hall and The Studio reminds us, time is relative: Lawrence’s lateness is measured against an American art history set to Eastern Standard Time. Drawing upon theories of art historical periodization (Gombrich, Kauffman) as well as Jacob Lawrence’s own philosophies of narrative building, I argue for a renewed attention to lateness as a subjective interpretive category, ripe for historiographic analysis.

Juliet Sperling is an Assistant Professor of Art History and Kollar Endowed Chair in American Art in the School of Art + Art History + Design at the University of Washington. For the 2022-23 academic year, she is a Barbara Thom Fellow at the Huntington Library, where she will complete a book about the convergence of vision and touch in American visual culture during the long nineteenth century. Sperling is Chair of the Association of Historians of American Art and a senior fellow and founding member of the Andrew W. Mellon Society of Fellows in Critical Bibliography.

Belatedness, Near and Far

Martha Langford, Distinguished University Research Professor, Art History; and Research Chair and Director, Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Institute for Studies in Canadian Art, Concordia University

Distance of country compensates in some sort for nearness of time; for people do not distinguish between that which is, if I may venture to say so, a thousand years, and that which is a thousand miles from them.

Edgar Wind, “The Revolution of History Painting,” 1938.

Belatedness obtains to “common sense” through a palimpsest of learned borrowings: Wind from Roger Fry, Fry from Jean Racine, and Racine, via his classical education, reaching back to Tacitus, where the link between reverence and remoteness – centre and periphery – informed military strategy in the provinces. In settler-colonial Canada, the mid-twentieth-century campaign to recognize photography as an art form and to institutionalize its practice and education can be pegged to a similar timeline: episodic dignification by Euro-American authorities who came to see and dutifully reported that Canadian modernist photographic practice was coming along nicely, albeit slowly.

Distant from photography’s metropoles, remote even from each other, Canadians’ lack of primacy is a recurring lament of its long Pictorialist period, and it continues to be mentioned through succeeding movements, from social documentary to photo-conceptualism. In a curious about-face, a collective project’s lack of originality might come to be praised, as in 1970, when Peter Bunnell, then curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, spoke at the Ottawa opening of BC Almanac[h] C-B. This fifteen-person collective had created a boxed set of artist’s books, which was exhibited as unbound sheets on the wall and in stacks. McLuhanesque messages in the medium were deskilling and mass communication. Bunnell tried his level best: “The photographs that you see on the wall are not original in any sense, indeed they are copies of the catalogues or of the book, the pamphlet. I think this is an extraordinary thing and I congratulate everyone who had something to do with it.” As Racine said of his contemporary Turkish stage characters: “They are looked upon early as old.” My paper will explore the twinned mystifications of time and territory in the writing of Canadian photography history.

Martha Langford is Research Chair and Director of the Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Institute for Studies in Canadian Art, a Distinguished University Research Professor in the Department of Art History, Concordia University (Montreal), and a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. Her most recent publications are two edited collections, Narratives Unfolding: National Art Histories in an Unfinished World (2017) and co-edited with Johanne Sloan, Photogenic Montreal: Activisms and Archives in a Post-industrial City (2021), both from McGill-Queen’s University Press. She is currently writing a history of photography in Canada.

“Yet-to-be-dismantled”: Elizabeth Bishop and Winslow Homer in 1974

Nicholas Robbins, Lecturer in History of Art, University College London

In 1974 Elizabeth Bishop gave a reading of her poems at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. At the core of the reading was a pair of poems that Bishop wrote about a relative’s paintings of Nova Scotia, where she lived when she was young. These poems, and the others she read, explored an attenuated reckoning with the hold that art has on historical perception: “A yesterday I find almost impossible to lift.” 1974 also saw Winslow Homer’s work shown in major retrospectives in Washington and New York, as well as the publication of an important monograph on his Civil War era work. At stake, as ever, was Homer’s vexed position in periodizing narratives of American art: whether his work should be positioned at the beginning or at the end of a narrative of American art’s relationship to historical reality. This paper considers the poems that Bishop read that day and the works by Homer displayed that year as parallel meditations on the transmission of information from the past. Both artists linger on the animation of environmental elements (ocean water, sprays and fogs, rhythms of frost and thaw) and on reverberating sound as mediums for images of history. In these figurations Bishop and Homer were concerned with fraught communications: historical messages that never quite arrive, or arrive only intermittently, “in snatches, first dim, then keen, then mute.” Like Great-Uncle George’s paintings, Homer’s work was always appearing too early and too late, both “flowing, and flown.”

Nicholas Robbins is a lecturer in History of Art at University College London. He is currently writing a book, The Late Weather, about the climate’s scientific, cultural and artistic histories in nineteenth-century Britain. His writing on the scientific and ecological significance of art has been published in The Art Bulletin, Grey Room, and Oxford Art Journal.

When did Indigenous art become “American”?

Elizabeth Hutchinson, Associate Professor of American Art History, Barnard College/Columbia University

In the past two decades, work by Native American artists has been increasingly integrated into textbooks and museum installations offering an overview of American art. This expansion of the canon might be seen as a response to the multiculturalism of the 1990s, a movement that frequently emphasized inclusion without attention to ongoing structures of cultural and political disenfranchisement, dislocation and dispossession. However, the first time Indigenous art was presented as “American” traces at least as far back as the 1971, when the Whitney Museum of American Art presented an exhibition of historical Native American painting and sculpture. Significantly, it occurred while Black Emergency Culture Coalition protests calling for institutional transformation that would bring Black art and artworkers into the centre of the Whitney’s practice. In the early 1970s, Indigenous culture workers in New York City, working in solidarity with the national American Indian Movement, were also organizing for cultural sovereignty. In this paper, I will situate the Whitney’s exhibition within the context of the Civil Rights struggles of the time. As I will argue, doing so offers insight into the art world’s current racial reckoning and offers some possibilities for thinking through what is at stake in “Americanizing” Indigenous art.

Elizabeth Hutchinson is the author of The Indian Craze: Primitivism, Modernism, and Transculturation in American Art, 1890-1915 (Duke University Press, 2009), numerous articles, and exhibition catalog essays on artworks by both Native and Settler artists from the United States. She has received awards for her scholarship and teaching, including fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Council of Learned Societies and, most recently, the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Her current research combines the methods of ecocriticism and indigenous studies to analyze nineteenth-century photography in the American West.

American Art Historiography, Slavery, and its Aftermath

Tanya Sheehan, Ellerton M. and Edith K. Jetté Professor of Art; Colby College

Belatedness: delinquency, lateness, tardiness. Surely this must describe the United States’ recognition of the social and cultural effects of 246 years of institutionalized slavery. Indeed, it was not until 2008—the same year that Americans elected their first Black president—that the US House of Representatives issued a formal apology to African Americans for slavery and Jim Crow laws that supported racial segregation. Yet no form of reparations for the descendants of enslaved people exists in the US to this day, and Black lives remain marked by what historian Saidiya Hartman has called the “afterlife of slavery–skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment.”

True to its cultural roots in the US, the field of American art history is characterized by a similar belatedness. It has been slow to recognize centuries of slavery’s shaping of visual production and has only begun to address historiography’s persistent devaluation of Black lives. This paper explores how historians have attempted to integrate slavery into their stories about American art, and the political implications of doing so. I also look outside the field for models that would advance or critically reframe these efforts. Special consideration will be paid to historical surveys of American art. What could a radical remaking of those surveys look like in the classroom, one that centres slavery across the history of art, as Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project has been doing for American history?

Tanya Sheehan is William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Art at Colby College. She has been a research fellow at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center for African and African American Research since 2012, and has served as executive editor of the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art Journal since 2015. Sheehan is the author of Doctored: The Medicine of Photography in Nineteenth-Century America (2011) and Study in Black and White: Photography, Race, Humor (2018). Her most recent edited books include the volume Photography and Migration (2018) and the exhibition catalogue Andrew Wyeth: Life and Death (2022). Current projects include a collection of essays on modernism and art therapy and a book that explores the subjects of medicine and public health in twentieth-century art by African Americans.