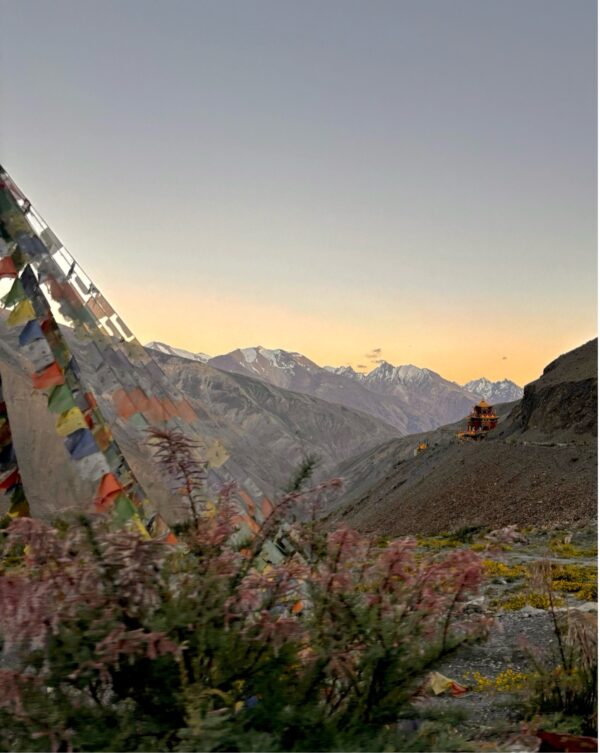

Encircled by a ring of snow mountains, at an altitude of over 4,000 metres, the Tibetan Plateau has fascinated those who live beyond it for centuries.

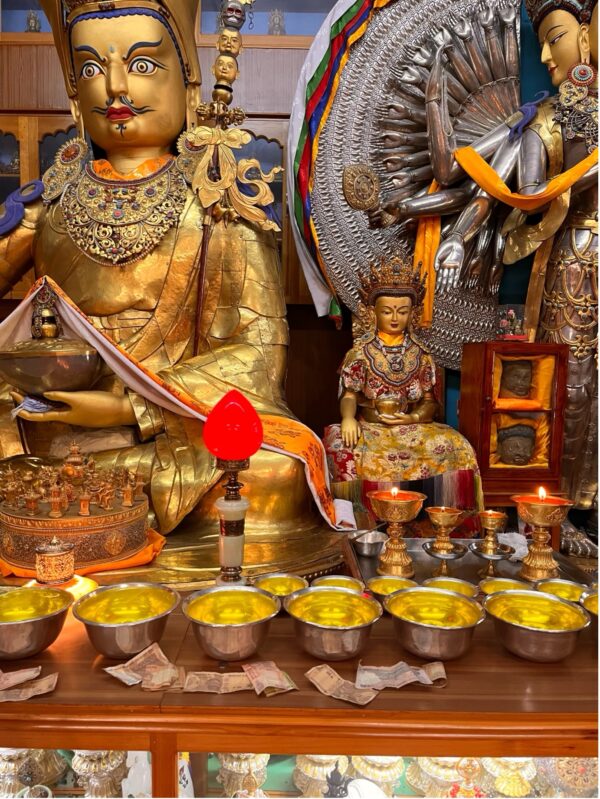

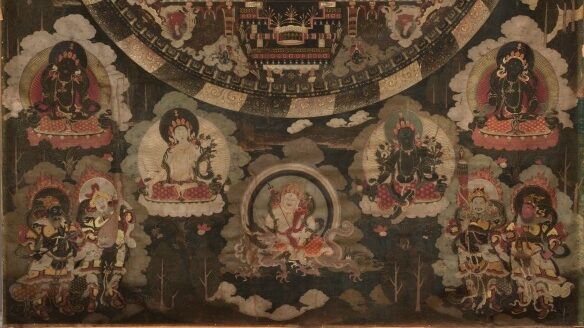

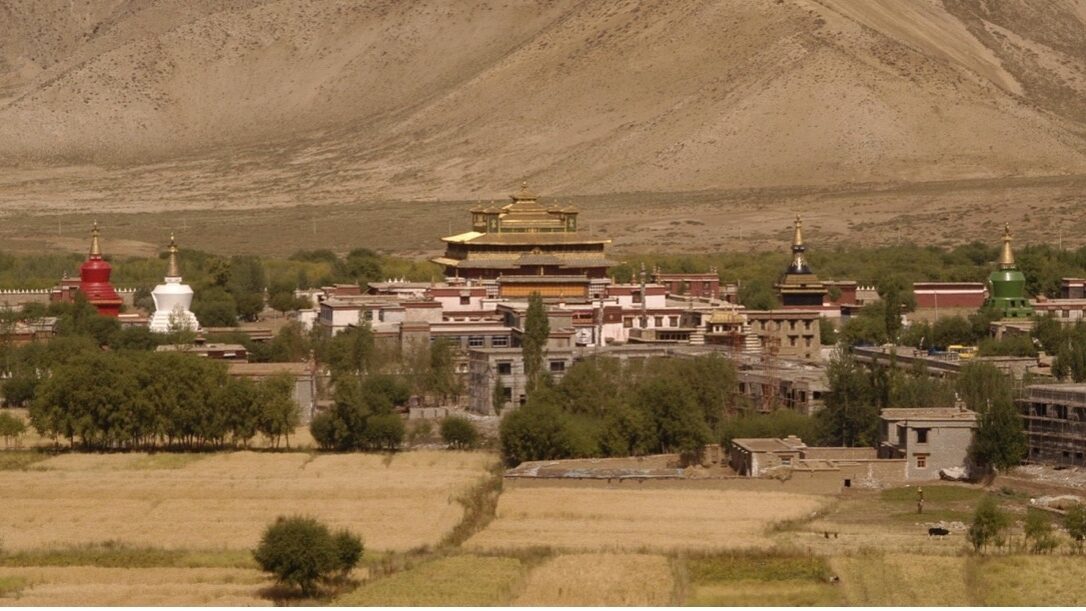

Periods of total isolation ensured the preservation of ancient practices, and the harsh terrain made travel by outsiders extremely difficult if not totally impossible during periods of contact. However, in spite of its unforgiving landscape, the Tibetan Plateau and the Himalayan region are home to a vast array of visually stunning, materially rich, and spiritually meaningful religious and secular art and architecture, formed through centuries of contact and intense exchange with the surrounding regions. Far from perceived total isolation and remoteness, this began with the inherently multi-cultural age of the great dharmarājas of the Tibetan Empire (c. seventh-ninth century CE) and was encouraged and enabled in particular by the sustained dissemination of Buddhism from India onto the plateau across the centuries. Positioned at the centre of the so-called ‘Silk Roads’, Tibet and the Himalayas are therefore of critical importance for understanding the wider story of Eurasian art.

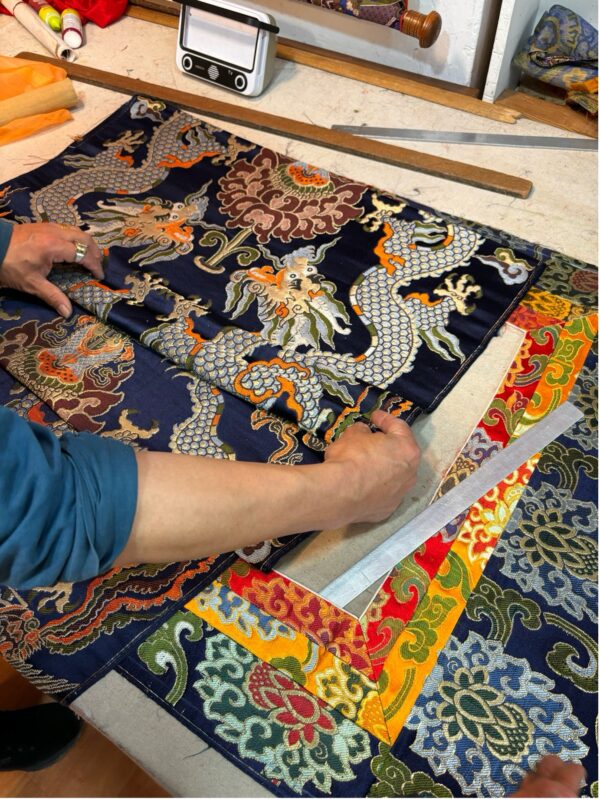

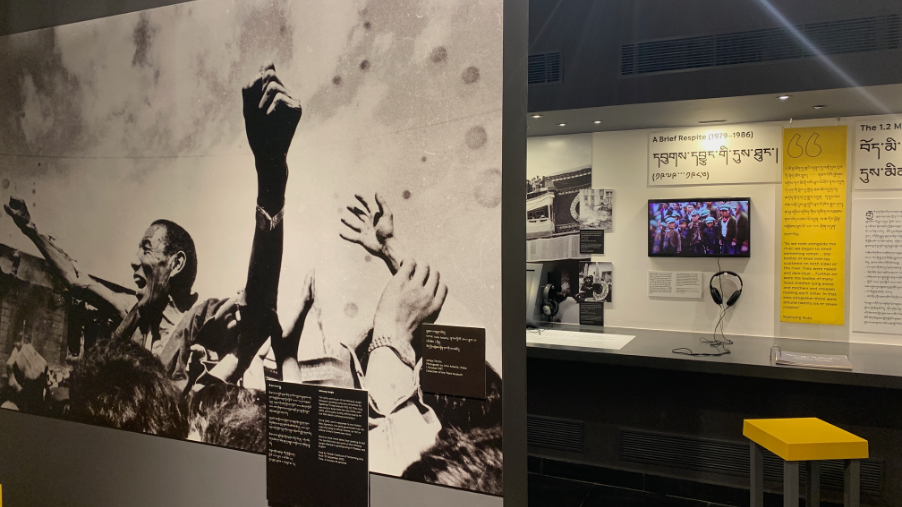

Following the illegal invasion of Tibet by the Chinese Communist Party in 1950, and the forced exile of HH The Fourteenth Dalai Lama in 1959, the art and material culture of Tibet has been systematically targeted and destroyed, especially during the so-called ‘cultural revolution’, inflicted on Tibet by the CCP. This linguistic, cultural and religious repression and colonial occupation continues today, and threatens the continued existence of Tibetan culture within Tibet. However, institutions established by the refugee community in exile work tirelessly to preserve the language, arts, culture and religion of the most peaceful nation on earth in spite of being unable to return home. Alongside new Tibetan refugee settlements in India, the art and material culture of Ladakh, Sikkim, Nepal and Bhutan, among others along the Himalayas, are culturally linked to the plateau through Tibetan Buddhism, while simultaneously having their own distinct histories, and are today important repositories of Himalayan arts.

The sensitive and historically accurate portrayal and representation of Tibetan material history outside of Tibet is therefore of critical importance not only for its own survival, but for the preservation of a historically truthful narrative of global history. This series of lectures aims to address the imbalance in western and ‘global’ outlooks of the History of Art that continue to overlook this fundamentally important region, and draw upon a global community of scholars and experts to inspire others to discover art from the Land of Snows.