Thank you for welcoming us! We appreciate meeting you today in your London-based studio to conduct this conversation amidst some examples of your work, which is extraordinarily rich in pictorial symbols. Your practice is a lot about traversing between different realms. How do you refer to the idea of the ‘edge’ in your art?

I think that’s probably easiest to start with how ‘Within’ started. ‘Within’ is the paracosm in my head that I depict in my work. Throughout my life, I have been very fascinated by fantasy in many iterations, whether it was the cartoons I watched growing up or the novels I read as a teenager, or even just the music videos I liked. I was always really interested in the whimsical aspects of things. ‘Within’ started when I was about twenty, or rather I became aware of ‘Within’ when I was about twenty years old.

The lore I have created for ‘Within’ goes: I was born a nameless alien thrust into a new existence, like many humans technically are. We are born as a compound of the ancestral coding that makes up our DNA, as well as the compound past lives we’ve lived, all condensed into this new body. In my culture, Yoruba culture, my dad’s culture, they do not name children till the seventh day. So the lore continues that when I was named Olubunmi, that is when Olubunmi comes into existence and begins to live my life with all its specific influences such as my family members, my lived experiences, my growing up in Lagos, all these things that form my sense of self today. However, that foundational being I was, that nameless alien in the first week of my life, [which] I now call Ó, fractures off and retreats into my mind and builds this world now called ‘Within.’ ‘Within’ also doubles across languages. Its equivalent in Yoruba is Ori, which in the culture’s cosmology refers to an individual’s essence or spark of consciousness. It also more literally means ‘head,’ which is perfect because ‘Within’ is situated in my mind, therefore my head is its vessel. The head is actually very important in Yoruba culture. For example, you’re not meant to just let anyone touch your head because it is believed to hold so much spiritual power.

So, returning to the lore and how it manifested in my real life, I was twenty years old, trying to make some art for an upcoming deadline. In those years, I found that when I tried to make art, it was unsuccessful or difficult, but when I just let it flow out of me, it worked. So it was then, in January 2020, that I made this series of portraits of myself, but each with a different mutation. This became the Hybrids Series, and these became the first characters to populate the world of ‘Within’ after Ó.

Could you show us some examples of these characters?

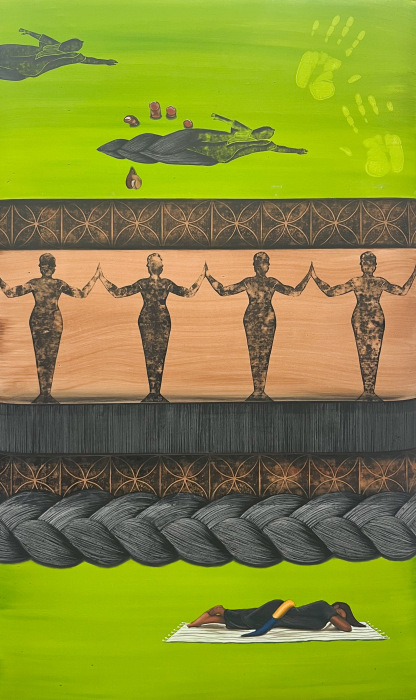

So, I had done six portraits, then an additional two afterwards (Fig. 1). In terms of these eight hybrid characters, each of them featured me with these mutations based on different aspects of my upbringing. These mutations spark different magical abilities in each of the hybrids. For example, the character Aruaro was born with tribal marks on her cheeks, and within these marks are a second set of eyes. When she opens these secondary eyes, she can see spirits and paranormal presences. Then you also have a character like Irunoji, who is depicted as having braids coming out of her eyes. Hair is actually embedded in the terrain of ‘Within’ as a nod to the world being in my head. So Irunoji has the telekinetic ability to manipulate the hair in the world, and thus she is the artist/architect of the world. Although she has these powers, she still enjoys her labour of love. Therefore, in some of my works, you see her building upon or maintaining the landscape. In A Cowrie Appears in The Sky (2022, Fig. 2), she is seen raking through Afro bushes using a larger-than-life comb.

My process involves lots of mind maps and storyboards, but I don’t make the works chronological. Each work comes to me quite spontaneously, then I end up piecing them together like a jigsaw puzzle. So it is the piecing together of the last four years of my work that creates this overarching lore. Although this world has arguably existed in my mind since birth, I was not aware of its existence and it was my arrival in the world at age twenty that triggered a domino effect of events. I had been meditating and envisioning a blank space in my mind, as you do. It was in that psychic space that a portal appeared and I went through it and first entered ‘Within.’ That is what is depicted in the work Surfacing (Fig. 3). It was on that first trip that I met Ó, the alien that had retreated into my mind. I call them Ó because it is a genderless pronoun in Yoruba, so it simply encapsulates all those past lives that the figure embodies. On the rare occasions I have depicted Ó in my work, I have shown them as a reconfiguration of the human form (see, for example, The Hand of Ó, Fig. 4). Their body constantly morphs and just keeps shifting around, so that you’re kind of literally seeing all the past bodies. So, that first encounter was frightening because Ó was a strange figure to me then. They ended up snatching a braid from my head, which they’d later use to create the eight hybrids, and that’s when I ran back to this waking reality. However, this world continues in my head both when I am there and not there. I am essentially transported there when I daydream. So, it’s this kind of flickering between those two worlds. It’s a paracosm, that’s the technical term for it.

You have your own Substack for your writing as well: can you tell us more about the relationship between your writing practice and your drawing and visual practice, and how the two collaborate?

I did my undergrad in Fine Arts at Central Saint Martins (CSM). Then, I used to write about contemporary art for my best friend’s blog called A’naala. That ended in 2020. I took a break from writing and didn’t start up again till I did my MA in History of Art and Archaeology at SOAS. I actually only really regained my confidence as a writer and art historian, and that is why I launched my Substack. Prior to all of this I did the Sixth Form IB (International Baccalaureate), here in the UK, which teaches you how to be a good writer. So, by time I go to CSM, where we have to show these portfolios of the works that we have made, I’d constantly have lots of writing, and some tutors would often complain saying, ‘You’re writing too much.’ One even suggested that I could be better suited for the curatorial or business side of the industry because I was so organised.

How discouraging, good you proved them wrong! It’s also quite stereotypical to view artists like that…

I feel like I generally had a disconnect with a lot of my tutors in the UK when I first moved here. Some didn’t see my strengths until later on. For example, the way the course goes in Sixth Form is that you’re encouraged to try out various techniques and experiment and eventually find your thing. So for the first sixty to seventy percent of the course, I was constantly doing something new and not excelling because I’m doing something that I’ve never done before. Eventually, when we were given the freedom to do whatever we wanted after experimenting, I returned to these pastel-on-paper drawings I had started doing at like age thirteen in Nigeria. So, I was an okay oil painter, a decent printmaker, then they saw those pastel drawings and that’s when they were like, ‘Oh wow, you’re actually really good at what you do’—which is why pastel drawing is my default today and the kind of work I always come back to. Even in my mixed media works now, the labour of love really comes in the drawing, for me.

Another kind of disconnect came for me in how my cultural background was understood. One of the things about CSM, really when you come into any international art institution as an international student, you have to do the legwork of introducing yourself before you can then introduce your work, because you naturally have to give them so much background information for them to be able to understand the context your work. So sometimes, when I showed my work then, it was read through a Black British lens, because that’s the mode of Blackness many people here are more familiar with. But I was born and raised in Nigeria. I don’t even have a British passport. I am completely Nigerian, and Nigerianness already has so much complexity within itself that I like to explore. Even to this day, many people viewing my work still do. They sometimes minimise it to only being about race and Blackness, which is present to some extent in my work, but that hasn’t been the sole conversation I am trying to have. For a long time, I actually didn’t even feel well-versed in that conversation because I’d grown up around Black people my entire life, in a largely racially homogenous country, so I actually did not really experience Blackness as a state of difference in my everyday life until much later in my life compared to the lens people usually try to view my work through.

Has that wrong lens being applied to your work changed over the past years, even though you didn’t go to art school that long ago?

It has shifted a bit, but that wrong lens is still very much there, with people from various backgrounds. I recently had a conversation with a British-Caribbean friend who is quite politically active, and he’s one of the most radical liberal thinkers I have as a friend, but he made very strange comment to me. He said that he loves my work so much, but that he just feels that it’s not political, and he thinks I could do so much more if I made my work political. I was like: ‘it’s not political to you because we’ve just lived very different lives. You are a man who’s grown up in England in an atheist household, where to speak about certain spiritual cosmologies is not taboo.’ Nigerian audiences, however, occasionally have rather strong reactions to my work, where it’s kind of ‘Oh, you shouldn’t be talking about that, or don’t say this lightly’—and I’m not taking it lightly! I’m studying it. In terms of who was buying my work early on, I didn’t have that many older Nigerians buy my work. Spirituality, religion, cultural theory is very political in the context of mine and many people’s existence.

What was it about the older generation? What was their hesitance?

They usually identify spiritually as Christian or Muslim, and when you can look at the religious imperialism that happened in Nigeria during the colonial era—they deemed all the traditional religions ‘fetish’ and ‘demonic.’ So, you still have remnants of that with older people, but even with people my age, just depending on the environments you grow up in. These people don’t always even like speaking about these traditions, or they speak about them with respect, which I do because I study many religions simultaneously and give them the same amount of respect.

Your own lens on your work is very historically informed. How did you begin engaging with these meta-narratives about spirituality’s entanglement with colonialism? Was it through personal study?

After having had the experience of constantly being perceived as Black British when I was Nigerian, I ended up doing my first Masters at SOAS in History of Art and Archeology, and that’s where I was able to study African art history specifically, and Nigerian art history. In terms of the realities of perceiving me as Black British, that means that art school tutors were constantly recommending Black British artists to me. So being able to go to SOAS and have the art history backing in Nigerian art history, where I was looking at the modernist portrait painters or even the idea of natural synthesis—which was in post-independence Nigeria, where Western techniques were taught, but then because Nigeria had gained independence, artists were looking to reconnect with their traditions. So, they were blending these Western techniques with traditional ideologies. It started in the 1960s, but that still trickles down to how I handle my work today.

I’ve been doing myself and people who truly engage with my work the service of now presenting the research and the work that I’m doing behind the scenes and building the work through my Substack. It’s called In Search of Magic and it’s about fantasy and magical storytelling. Currently I have mostly articles with African cosmologies that I have been looking at, but I also go into fantasy because I love playing The Sims and I love playing video games and I love Marvel movies.

I was hesitant to say that the characters, when you introduced the hybrids, reminded me of superheroes, but I thought I might be simplifying it or putting a Hollywood lens on it.

I actually reference Hollywood, sci-fi films, and comic book culture a lot. Even when I use the braid in my work, there’s so many connotations to that. I use it literally because the world is in my head, and so instead of grass I have hair growing out of the ground of the world. The hair then forms the botany of the world, like creating Afro bushes, for example, like braided hedges. Also, in terms of the idea of cornrows, looking at a pop culture lens. When you usually have aliens arrive on earth, they arrive in the cornfield, in the cornrows. So having the alien Ó and the hybrids live amongst cornrows is a nod to those sci-fi movies. That is why in a work like Surfacing (Fig. 3), you see me arriving to the world amongst the cornrows.

One thing to add to the lore of ‘Within’: after I first accessed the world and returned to my waking reality, the portal between the worlds stayed open. So, when I meet people in my life, versions of them are subsumed into the world. For example, I meet you, and there’s a version of you that lives on in my mind based on my perception of you. So as a result, the humans of my life exist in the world of ‘Within’ as these cross-reality migrants. That migration is what I depicted in my first solo exhibition (Hybrids, 2020; Fig. 1): the works showed how these cross-reality migrants arrived in this braided forest that is at the centre of the world. It showed all the people I have kind of engaged with, some family, some friends, some passers-by sifting through these different braided compositions, trying to navigate their way through this new world. They are all lost in this labyrinth before one of the hybrids comes to bring them out of the wider world.

I usually end up being the one to curate my exhibitions because of how tight the narrative sequence is. I’ve curated all my solo exhibitions, except for one that I co-curated in Lagos (Outside, 2023). I tend to have very little use for external curators for my solo exhibitions because there is only so much wiggle room because the narrative and chronology is so specific and concise. I am also a curator, writer, and art historian in my own right, so curating is part of the art-making for me. I also usually prefer to know the space before I make a body of work, because that’s how I know how long of a narrative I can do, and the space dictates that. I would want each room to have a different feel. I like to punctuate space. A signature of my curatorial style for my own work is black strips on the wall that can segment the narrative because it lends itself to the storytelling.

This is such a literal and metaphoric handling of the edge, because you go literally out of the edge, then back into the edge. It must be fascinating to watch people walk around, follow the storyline.

I don’t always like watching people go through my shows. I’m introverted, so I’m not someone who’s trying to be talking to everyone all the time. Also, I might see someone walk by a sequence of works too quickly and then I’m like ‘Oh no’ [laughs]. So, I don’t want to expose myself to certain things, I protect myself from that because there is so much unacknowledged work.

When I first started out, I opted for not having exhibition texts in the space, but mind maps instead. That caught a lot of people’s attention. I am really interested in these disparate things: architecture, pop culture, sci-fi movies, video games, cultural theory, psychology… It’s really hard to encapsulate all of that in just paragraphs. So instead, I used to do these mind maps. I have only done them in two exhibitions, but they remain part of my process.

Did you move away from this because you didn’t want to be so revealing about the associations?

No, it was just that I have now done four solos. The first two, I had the mind maps communicated by me, and then the third one was my first co-curated solo. The curator had written an exhibition text, and I tried to take a step back and allow myself to see what it would look like if someone else curated the show. I relinquished some power. Then by the time I did my last solo, Lands of the Living (London, 2024) my dad passed away right before, and so the entire exhibition was about grief and afterlife and the experience of afterlife in the context of ‘Within,’ so I was extremely in control of the curation of that.

In that body of work, I really leaned into the juxtaposition of the drawn versus the printed in my work because the former represents physical, seen presences, whilst the latter represents more ghostly, spiritual presences, showing the interaction between ghosts and humans. This actually ties back in with my writing: When I was at SOAS (2021-2022), my thesis was on Nigerian masquerades. I was looking at the Egúngún masquerade, which is a masquerade that comes out during funeral rites, and the whole idea is that this masked performer comes out and a deceased spirit is believed to possess the body of the performer and access the land of the living again. The performer becomes an avatar for the ghost. The masquerade became the conduit for me to explore grief after the loss of my cousin and then the loss of my dad. And so, like I said, the performer becomes the avatar for the deceased spirit, but since I make fantasy worlds, I asked ‘where does the spirit of the performer go?’ I then theorised in my last exhibition that maybe the spirit of the performer switches bodies with the ghost. I depicted ghost-bodies as patterned clouds in the sky as a reference to death as transition, which is also a thing in Yoruba cosmology. That transition is echoed in the processes of evaporation, precipitation, and condensation, and how the water is ever present even in cloud form. That is why I depict clouds as untethered beings floating in the sky and the humans as these grounded beings at the bottom.

Hands are certainly very prominent in your work.

Yes, the braided, printed hands are there to represent the idea of the Hand of the Divine and the unseen labour of the divine.

It’s like a fantasy novel!

Yes, I’m currently working in graphic novel too. It gradually summarises the world I have built so far. I imagine that I might develop it in volumes, as my career goes on and I continue to build the world.

The spiritual beings are just flying around at this point?

Well, yes. They were first seen flying around in my degree show at the Ruskin, in this body of work called Loose Spirits (Fig. 5). They were just everywhere; I had them on the floor and you could see the hands swarming to get them. In the work Reaching Through Worlds (Fig. 6), you actually see my hand reaching for them as well.

Could you tell us a bit more about the significance of the weave in your work?

I find the weave in particular all encompassing of the things that I do. I’m just weaving together so many things. The weave exemplifies that combining of so many disparate elements. I even also have the interlacing border in my work as the border that delineates the spiritual and the physical realms. Art historically, that is also a nod to the interlacing motifs in art from the Benin Kingdom, which is of my mum’s culture.

Your paintings are quite photorealistic. Does photography play a role in your work at all?

In the process, yes. I often to stage a photograph for my preferences and use it. Mostly, I work with the selfie, and I often video myself doing different poses. Very occasionally, I’d ask people to pose for me, so I try to let that be more natural and organic. Often, I’d go around shooting a burst of photos of random people that I pick up. For me it was like this natural pulling of my reality into my fantasy world.

There is an interesting tension between letting go of control and then conducting control upon yourself.

Yeah, I tend to create this distance between the viewer and my work. Some people have suggested that I should just do a full room installation and let people be immersed in the world, and I think: why would I want people to be immersed in the world? It’s my world and I am very protective of myself. Why would I let people intrude on my world like that? That is why my work is presented flat on a two-dimensional plane. You’re allowed to look at it, but you are not in it.

You’re basically answering one of the questions that I was trying to formulate early on when I thought ‘oh, it’s like an installation,’ but I was wary of insinuating that it’s immersive because of the medium used, because of the flatness of the pictorial. You’re returning to the idea of the picture as window.

Could you now tell us a bit about your relationship to where you grew up?

I go to Nigeria all the time. Nigerian people often reach out to me asking me to work on short-term projects without realising that I don’t live in Lagos.

You’re in between worlds as well.

Yeah, that is why I developed hybrid and alien characters in my work. That was my way of commenting on the cultural migration that I had experienced. For me, it wasn’t about just being a Black person in the UK. It was about my formative years being in almost solely created in a Nigerian context then starting to integrate Britishness from a certain point. It is a very different experience of hybridity than growing up with multiple simultaneously. There is a culture shock that makes you reevaluate so much about your sense of self.

I think people step into the trap of wrong association having their vision tainted by the dominance of whiteness in Europe, instead of thinking about other realities that exist outside of the West, where things are not in relation to whiteness.

I mean, at the same time, there is inherently a sense of Britishness in Nigerianness because Nigeria was colonised by the British. The way that I explore this is just not in the same way that someone who has lived their whole life here would, because our experiences are different. For example, even my last name is Brazilian-Portuguese because of the slave trade. My great-great-grandfather was enslaved in Brazil, and when he came back to Nigeria, he had a Brazilian surname. It is originally ‘Augusto,’ but there is an ownership that is created in that new spelling. There is actually a sense of creolisation to it because many people who don’t think too hard about it mistake it for a Yoruba name. That’s why I actually get kind of offended when people spell it the Portuguese way.

On a different note, I feel like architecture is a point of entry that I use quite a lot to explore colonial legacies, because in Lagos there is still a lot of colonial mentality with the idea that western ways of doing things are better or the default. I grew up amid this mentality and I think it is very evident in the country’s architectural landscape, especially in Lagos. There are often these white buildings with small windows, which doesn’t make sense for the climate because it hinders ventilation. Small windows are for trapping heat, which you don’t need in Nigeria. The white walls also get dirty very quickly because we have dusty wind. So one of the references I make to climate is the breeze block as a pattern in my works (Fig. 6, Fig. 7). You see it a lot in tropical modernist architecture, as it lets the breeze come through, and in that sense breeze is so emblematic of existing truly and building worlds and nations accordingly.

What about your favourite sci-fi stories? You mentioned so many good examples.

I love Marvel and its universe. Avengers: Infinity War and Endgame were life-changing for me. I actually started my world-building practice because of Marvel. It was when Infinity War came out that I finally understood how intricately connected the cinematic universe they’d been building was. All the movies play a role, and I thought the storytelling was out of this world. Actually, when Infinity War came out, I had just moved to The Hague for my study abroad at the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague. I went during winter, and it was cold and depressing. So, I was mostly in my room playing Sims and watching all the Marvel movies in sequence. I also just got very interested in the idea of the franchise in the context of world-building, so I was also looking at The Fast and the Furious movies. At this point, I was nineteen, so it was the year before I ended up making ‘Within.’ That was foundational for me in terms of thinking about what I could do.

I’m also quite influenced by comic books, like the structure of having panels. That is why I have so many borders in my more recent works. I have basically created these different borders that signify different things in my work. For example, the spiritual border demarcates the spiritual and physical. The breeze blocks often demarcate a change in space or location. The weaved borders indicate the passage of time. All three borders can be seen in a work like Apparitions Across Dimensions (Fig. 7).

Does the hair signify time because of the growth of the hair?

Yeah, it is just the idea of line and continuity. It is mostly in my last body of work that I did this. It also references comic book culture with the borders between story panels.

We started with the edge and then you organically circled back to the edge. Without us asking for it, you arrived at borders, and the value that lies in crossing them, which is our biggest take away from this enriching conversation with you. Thank you for your time and the many insights you have given us.