On 12 October, 1762, the London Evening Post published ‘A Song on the conquest of Havannah,’ beginning with the verse:

Now England’s victorious

Our conquests more glorious

Than those of Eliza or Anna

Freedom drew honours sword

Courage gave us the Word

And our Hearts of Oak storm’d the Havannah.1

A month earlier, on 10 September, the London-based newspaper Lloyd’s Evening Post printed the number of casualties following the capture of the Cuban port, calculating a total of 195 killed, 383 wounded and 120 missing.2

Two years later, in 1764, Lieutenant Philip Orsbridge (d. 1766) produced a set of prints documenting the siege of Havana, based on oil paintings by Dominic Serres the Elder (1722-1793), after sketches by Orsbidge himself. Serres would later refine one of these prints, depicting the landing of British forces at Cojimar Bay, as a grand oil painting for the Keppel family. This painting is now located at the National Maritime Museum with the title The Capture of Havana, 1762: The Landing, 7th June (1770-1775, Fig. 1).

Each of these of printed items—the poem, the casualty list, the image by Serres—exists as a representation of the soldiers and sailors who fought in the British capture of Havana in 1762 during the Seven Years’ War. Each representation, to varying degrees, is characterised by the anonymity of these individuals. The song conjures a sentimentalised vision of British heroes, with reference to David Garrick’s so-called ‘Hearts of Oak,’ thus constructing a mythology of national triumph featuring an anonymous mass of loyal champions.3 The calculation of casualties offers a summarising number in place of individualised men. Serres’ image presents the might of Britannia’s forces, with miniscule sailors and soldiers functioning as cogs in a well-oiled machine.

The performance of anonymity in Serres’ painting The Capture of Havana, 1762: the Landing, 7th June(henceforth ‘The Landing’) buttresses a collective memory of British military victory in the eighteenth century. This process can be clarified and dissected by using Joseph Roach’s concept of circum-Atlantic performance. In his 1996 book Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance, Roach writes that ‘any performance of memory also enacts forgetting.’4 Serres’ oil painting, completed in the early 1770s, is indeed an articulation of the past, a performance of memory. Thus, within the framework of Roach’s theory, we must consider what is being forgotten. In the anonymity of the soldiers and sailors—an anonymity enacted in other examples—we must wonder: what is being erased, overlooked, or shunted to the edges of memory?

Roach posits that culture reproduces itself in a process of ‘surrogation,’ whereby voids left by death or loss are filled with imperfect substitutes. Because they are imperfect, these surrogates provoke both the memory and forgetting of the predecessor. Surrogation, in its imperfection, also relies on a constant performance, in which enactments of authenticity may ‘congeal into full-blown myths of legitimacy and origin.’5 Collective memory therefore ‘requires public acts of forgetting’ to maintain these new mythologies.6 Though based in performance theory, scholars of art history such as Esther Chadwick and Geoff Quilley have applied Roach’s concept to material culture from the early modern Atlantic World with engaging results.7 As they demonstrate, Roach’s framework encourages scholars to consider cultural artefacts and customs as performances of memory, and to suggest what is being surrogated and forgotten within that performance. I therefore consider several candidates for surrogation in Serres’ The Landing. These include the realities of conflict in the Capture of Havana, the controversial figure of the eighteenth-century sailor, the instability of Britain’s empire in the third quarter of the eighteenth century, and histories of the transatlantic slave trade and the Industrial Revolution.

Hammad Nasar has argued that there are distinctly ‘empire shaped holes’ in the historiography of British art.8Arguably, these are not holes, but sites of epistemological surrogation, in which the looming presence of empire in British art and material culture has been avoided and replaced by other analysis. However, even cursory research makes it apparent that imperial ideology and identity were quite openly incorporated into visual culture in eighteenth-century Britain. The grudgingly guilty silence where discussion of empire should be leaves history only half told. My exploration here aims to understand how imperial identity was portrayed in the eighteenth century, and thus the processes by which it was created. Hopefully it will also in some small way contribute to scholarship recovering the individuals whose lives and stories were forfeited at the altar of empire.

In order to interpret how the unsavoury and inconvenient realities of eighteenth-century British Empire have been silenced in this performance of collective memory, let us first consider the context and background to Serres’ painting. While an exact date for its completion has not been established, it was painted between 1770 and 1775 as a commission from the Keppel family, along with at least thirteen other pictures illustrating the events of the capture of Havana.9 Three central commanding figures of the campaign were brothers from the Keppel family: George Keppel (1724- 1772), the third Earl of Albermarle, was the army’s commander-in-chief; William Keppel (1727-1782) led the attack on Havana’s Morro Castle; and Augustus Keppel (1725-1786) was commodore of the British naval force.10 Augustus Keppel may also have been the patron of four large canvases painted by Serres documenting the capture of Goree, an island offshore of Senegal.11 Serres, meanwhile, was an artist of not insignificant acclaim, and was among the founding members of the Royal Academy of Arts in London. His commissions from the Keppel family perhaps came about through his collaboration in print projects illustrating the battles of the Seven Years War.12

1759 became known in Britain as the ‘Year of Victories.’ By this point, the military was the nation’s largest borrower, spender, and employer, and, according to Douglas Fordham, the Seven Years’ War challenged British artists to ‘find ways to ally themselves with the “fiscal military state,”’ (a term originally coined by John Brewer).13 Entrepreneurial publishers soon recognised the potential for profit behind public desire for illustrations of British military triumph.14 Richard Short, a purser in the British navy, was one such publisher.15A skilful draughtsman, Short drew several ‘on the spot’ sketches of the capture of Quebec in 1759, and later commissioned artists to create paintings from these sketches that would in turn be engraved for publication. Of these twelve paintings, four are signed by Serres, and dated 1760. Short and Serres would similarly collaborate in later publications of six views of Halifax, Nova Scotia, and six views of the capture of Belleisle, Brittany.16

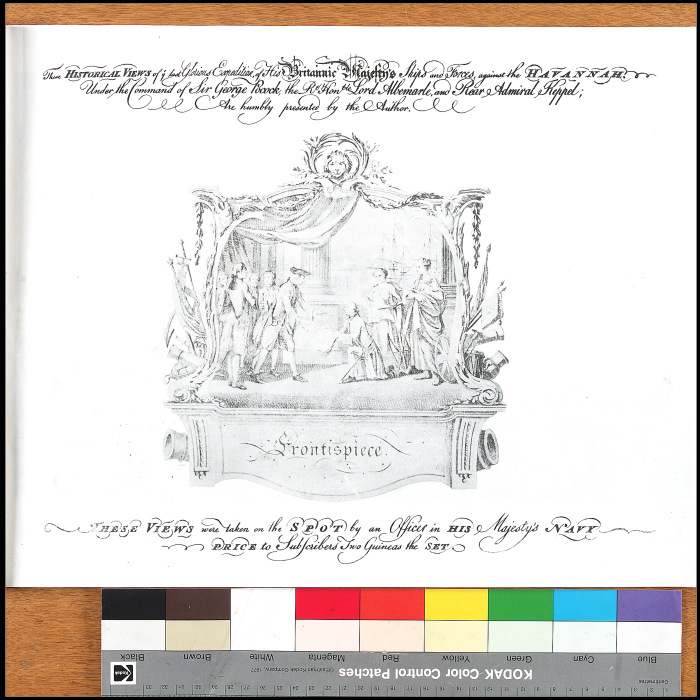

Lieutenant Philip Orsbridge, perhaps inspired by Short, embarked on his own printing project illustrating the conquest of Havana, having served there on the ship the Orford.17 Advertised in The Public Advertiser on 21 May 1765 as ‘Twelve True Historical VIEWS, representing the Whole Process of the Glorious Conquest of the HAVANNAH, taken by an Officer on the Spot,’ the scenes were originally sketched by Orsbridge, then painted by Serres, before being engraved by Pierre Charles Canot and James Mason.18 The series was funded by a speculative system of subscription whereby interested parties paid in advance. The twelve views, plus an engraved frontispiece, were titled Britannia’s Triumph (1764, Fig. 2). Serres would later rework his paintings for this publication into more refined works for the Keppel family.19 The Landing appears to be some amalgamation of Plates V and VII. While Plate V purportedly depicts the same events of 7 June 1762, Plate VII’s composition is more similar to that of the painting, although is captioned 30 June (1764 – 1765, Fig. 3 and Fig. 4).

Popular European prints in the eighteenth century—particularly those depicting unusual subjects like battles or overseas lands—are regularly captioned with the phrase ‘taken on the spot’ or ‘drawn on the spot.’ Almost every print in Britannia’s Triumph includes this mantra. This emphasis on immediate and faithful transcription reinforces the professed veracity of the views, contributing to a ‘narrative of authenticity’ and assuring the legitimacy of their documentation.20 Yet, filtered through the artistic manipulations of Serres, the images employ typical compositional devices of maritime painting, as inherited from Willem van de Velde the Elder and the Younger—the seventeenth-century Dutch father-and-son duo thought to have reinvigorated a trend for marine painting in Britain.21 Such devices include a high, all-encompassing viewpoint; ships and coastlines as repoussoir devices that frame the composition and guide the viewer’s eye; small staffage figures indicating scale, and generally romanticised elements, such as the rays of sunlight emanating from candyfloss clouds in Serres’ The Landing. Thus, the images imbued with this ‘on the spot’ veracity are in fact painterly arrangements, designed to be clear, digestible, and perhaps suggestive of a message evoked by titles like Britannia’s Triumph. Serres’ later 1770s painting, The Landing, performs a jingoistic narrative of almost predestined British military superiority. This narrative is established not only through the painting’s composition—the light of sunrise illuminating proudly raised flags of Britain’s infinite fleet—but in its association with such a blatantly patriotically minded print series.

The victories of the Seven Years’ War are of especial importance to the confirmation of Britain as a powerful imperial maritime presence within the Atlantic World. Sometimes interpreted as but another ‘battle’ in a second Hundred Years’ War between Britain and France that spanned the eighteenth century, this was one of several Atlantic conflicts based in competitive imperial commercial expansion.22 At the culmination of the Seven Years’ War, recognised in the Treaty of Paris of 1763, Britain had achieved significant territorial gains in North America and proved its unsurpassed maritime strength. Arguably, it is this victory which marks the apex of Britain’s Atlantic Empire, sometimes referred to as its ‘First’ Empire.23

The concept of British Empire is a slippery one, with a disputed history. David Armitage identifies an ideology of British Empire which crystallised in the 1730s and 1740s around several core characteristics: it was Protestant (or more specifically not Catholic), commercial in character, proclaimed freedom for its inhabitants, and was maritime-based.24 This ideology of Empire infiltrated the character of Britain’s state and its identity. Armitage writes that ‘Empires gave birth to states, and states stood at the heart of empires.’25 National identity was increasingly expressed in terms of commerce, and imperial maritime power. As John Campbell wrote in his 1785 naval history, Lives of the British Admirals:

We are a commercial nation … The great figure we make in the world, and the wide extent of our power and influence, is due to our naval strength, to which we stand indebted for our flourishing plantations, the spreading of British fame, and … British freedom, through every quarter of the universe.26

Illustrations of events from the Seven Years’ War were thus saturated with metaphorical allusions to imperial-maritime identity, nodding to Britain’s colonial acquisitions and its navy’s dominance. The title Britannia’s Triumph offers proof of the ubiquity of eighteenth-century associations of maritime dominance with national identity.

Serres’ painting thus acts as a performance of British imperial-maritime identity. In what follows, I will unravel the system of signs reproducing that identity through visual and contextual analysis. Notable absences are filled with replacements—ships and a collective workforce replace individuals. A detached viewpoint replaces personal perspectives. Eloquently composed arrangements replace chaotic and messy battles. The majestic victory ship replaces the slaving ship of the Middle Passage. All these replacements are acts of silencing, which are fundamental to a collective memory of imperial maritime success. Empire is a geographical space, an identity, a performance of power, but it is also a delicate façade of fantasy.

Each print from Britannia’s Triumph and the subsequent paintings for the Keppel family adopt the same high viewpoint of The Landing, with a low horizon and expansive vista of elegant ships. Ships, rather than people, are the true protagonists of the scenes. Consequently, the spectator is kept at a restrained distance from any of the grit and smoke and struggle taking place at sea level. While Serres offers some detail of difficult labour on the shoreline at the left foreground, these figures pulling barrels and ammunition ashore recede into ill-defined blurs. The composition settles around the grandeur of the fleet, particularly the ship just right of centre. The overall impression is one of a unified, symbolic force, rather than a group of individualised labourers. As Sarah Monks has written, the images reduce what was a gruelling months-long campaign in which thousands of men died from disease and battle into ‘consumable highlights.’27

The marginalisation of the individual perspective in favour of a unified workforce, whose shared interest is consolidated by the ship’s nationalistic symbolism, can be interpreted with Marxist theory. In his seminal publications Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea and The Many- Headed Hydra (with Peter Linebaugh), Marcus Rediker calls eighteenth- century sailors ‘workers afloat,’ using a Marxist lens to reanalyse the idealised fantasy of eighteenth-century British maritime power offered in Serres’ compositions.28 According to Rediker, the ‘work, cooperation and discipline of the ship made it a prototype of the factory.’ In fact, as Peter Way has shown, many mid-eighteenth-century recruits were originally from occupations made increasingly redundant by the Industrial Revolution, such as manual labourers, textile workers, shoemakers, and tailors.29In this context, the ship itself becomes an engine of the Industrial Revolution. Indeed, the wars of the eighteenth century were in large part the result of expanding commercial and trading ambitions, bound up in the developing industries that featured or depended on commodities such as cotton, lumber, furs, tea, sugar, and enslaved individuals.

Acting as a surrogate for the Industrial Revolution, the ship recalls a history correlated with yet often distanced from the conflict depicted. It is not uncommon for conventional historical retellings to consider the Industrial Revolution and eighteenth-century colonialism as separate narratives. However, as contemporary scholarship has come to recognise, colonialism supplied a number of the conditions facilitating Industrial explosion in Britain; including the injection of wealth and raw materials, such as cotton. Supplies of raw materials and wage goods (such as corn) allowed for cheaper labour and more profitable industrial investment in Britain.30 In turn, the Industrial Revolution eventually led to greater inland expansion in colonies via migration from overcrowded Industrial metropoles, and a greater demand for these raw materials. As in George Robertson’s or Philip de Loutherbourg’s depictions of Coalbrookdale, an industrial centre for coal mining and iron ore smelting, individuals in Serres’ maritime views are portrayed as akin to cogs in a system, small and unidentifiable. Focus is firmly located in communal effort.

The actualities of the individual’s experience during the capture of Havana are forgotten in this performance of memory. Death and destruction have been scrubbed from the surface of Britannia’s Triumph. In reality, the campaign to take the Spanish American fort resulted in the death of 40% of the 14,000 soldiers involved, predominantly from illnesses like yellow fever and malaria, which continued to kill men after victory was declared.31 James Miller, a soldier from the fifteenth regiment, recalls in his memoir that ‘the fatigues of this Siege pass description,’ describing how men were required to carry sandbags over two miles, amidst grapeshot, along a path nicknamed ‘bloody lane.’32 Miller writes that ‘the bad water brought on disorders, which were mortal, you would see the men’s tongues hanging out parch’d like a mad dog’s, a dollar was frequently given for a quart of water.’33 He complains of the disparity in the distribution of loot taken in Havana: while the share allotted to George Keppel, the Earl of Albemarle, was about £122,697, each private soldier received a little over £4.34 Miller queries ‘whether, after the most extraordinary fatigues, in such a climate, the blood of Britons should be lavish’d to agrandize individuals.’35

This personal, visceral account stands in contrast to the narrative told by Britannia’s Triumph. Indeed, in the context of such recollections, the title of Orsbridge and Serres’s collaborative print project takes on a grimly ironic tone. It is especially ironic if one speculates as to whether Serres’ later paintings, including The Landing, commissioned by the Keppel family, were paid for with the money obtained by Albemarle during the siege. Regardless, Serres benefits from a system which encourages the marginalisation of individual sailors and soldiers. The detached, withdrawn viewpoint in The Landing exemplifies that marginalisation. Such tactics again calls into question the extent to which the phrase ‘on the spot’ is but a performance, a subjective authenticity.

Overarching views of Britain’s powerful fleet substitute for the individuality of sailors and the reality of conflict in these images of war, intended for public consumption. Not only does this marginalisation perpetuate a system which tangibly increased the wealth of the elite classes, it also glosses over vulnerabilities in Britain’s navy. To depict the realistic, unpleasant experiences of the individuals who fought and worked at Havana was to acknowledge that the campaign was not one of easily achieved victory. Instead of pain, labour, disease, and death, Serres offers the British public visualisations of scripted engagements performed by the majestic ship.

Another reason for the erasure of individuality might be exemplified in Miller’s blunt critique of Albemarle’s aggrandisement at the expense of Britons and the resentment it entails. Discontent amongst sailors and soldiers was increasingly widespread after the campaign in Havana. Some regiments were left in Cuba, where they continued to suffer from disease. Others, expecting to return home, were in fact sent to North America, while many faced disbandment as the military forces began to decrease its numbers following the cessation of hostilities in 1763. Mutiny occurred within the forty-fifth regiment in 1747, and again in 1762, and at Quebec in 1763.36 Later, in 1797, there were significant naval mutinies at Spithead (an anchorage near Portsmouth) and the Nore (an anchorage in the Thames Estuary) protesting poor pay and living conditions. Simultaneously, numerous sailors turned to privateering to escape abject conditions on naval and merchant ships.37 Such ‘unscripted’ actions of the naval lower classes contributed to the figure of the sailor as one ‘veering between extremes of patriotism and treachery, obedience and subservience.’38 On one hand is the figure depicted in David Garrick’s ‘Hearts of Oak,’ the ‘jolly tars’ devoted to protecting Britannia; on the other, the sailor exists as a barely contained suppository of alterity and revolt, existing literally at the edges of British society, both within and without of the nation. The idea of sailors’ loyalty is also complicated by the reality of impressment and slavery, realities which make the opening stanza of Garrick’s 1759 song especially distasteful: ‘To honour we call you, as freemen not slaves / For who are as free as the sons of the waves?’

Any attempt to portray the individual sailor thus raised the spectre of how to depict this many-faced, controversial figure: the jolly tar, the mutineer, the slave, the impressed prisoner, the privateer. It was easier for Serres, and perhaps politically more desirable, to present the navy as an efficient system, each task carried out by willing and faceless labourers. In The Landing, miniature men climb rigging, pull barrels ashore, erect tents, and row to land, all contributing to an orchestrated design rather than focusing on the efforts of any individual (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6). Serres maintains the conventional image of what Geoff Quilley has termed the ‘robotic heart of oak’—functional machines of work and warfare, painted in a rosy veneer of happy patriotism and willing duty.39

Another printed source manipulating the complex figure of the sailor into something more robotically benign is found in the ‘Articles of literature and Entertainment’ from the London Daily Advertiser on 23 October 1762.40In this presumably fictional letter (as implied by the section header), the reader is offered an idealised version of the sailor. Like the phrase ‘on the spot,’ attributing the letter’s authorship to a sailor performs a ‘narrative of authenticity.’41 This is a literary manifestation of the ‘jolly tar,’ both loyal and jovial, prepared to die on request. He writes that ‘since we must all one time or other bear away for death’s harbour, as I only wait for sailing orders, I never mind when it is.’ The nonchalant sailor also makes light of the battle itself: ‘give the Dons their due they stood a good drubbing that they did … I never saw better sport for all the time it lasted, nor more bullets put about in so small a place.’ He jokes about ‘shaving the Don whiskers.’ Such a casually light-hearted perspective is markedly different to Miller’s first-hand description.

The ‘letter’ ends with our cheerful ‘tar’ assuring that he remains ‘Old England’s friend, and God bless their Majesties once more … not forgetting the Duke of Cumberland … He has sent as fine a parcel of officers here, general and all, as ever put a scarlet coat on.’42 Not only is this ideal sailor almost witlessly chipper, he is pointedly appreciative of his superiors, without Miller’s suspicion of official corruption. His persona is constructed from patriotic clichés. An eighteenth-century audience could thus graft this persona of the sailor onto Serres’ faceless and anonymous mass of workers, as Serres includes few markers of individuality to prevent us from doing so. Working in tandem with printed propaganda such as this (or Garrick’s Hearts of Oak, or A Song on the conquest of Havannah), Serres’ depiction of anonymous labourers neutralises any threat posed by the heterogeneous, unruly reality of the sailor. Individualism is surrogated by anonymity, yet this surrogation is imperfect, a selective memory which depends ‘crucially on forgetting’ accounts and experiences like that of Miller.43

It should be noted, however, that the advantages of anonymity are complex. While the anonymity evident in Serres’ painting—as in the prints, poems, and list of casualties mentioned above—builds on a myth of British imperial unity and loyalty of its navy, it also allows for personal interpretation. A viewer could project their own experiences into that anonymity—the mass of soldiers in Serres’ painting could include a loved one; or a sailor could see, process, and understand his own experiences while looking at countless faceless versions of himself. But even in this case, where anonymity acts as a useful conduit for situating the personal within the collective experience, the overarching narrative of ‘Britannia triumphant’ is still palpable.44 It forces individual experience to be understood through a prescribed lens.

As printed ephemera bolstered an eroding fantasy of the undisputedly loyal sailor, it simultaneously buttressed the vision of British imperial-maritime dominance. National identity is not an objective reality, but rather a fluctuating construction, one erected in the repeated enactment of a countless minute performances. Indeed, each source considered thus far is a performance projected into the public consciousness, fortifying and perpetuating the ideology of ‘Britannia triumphant’—a stable, united, imperial-maritime nation. Such fortification is especially necessary against the reality of a mid-eighteenth-century British empire in flux, with constantly shifting territorial possessions.

In this context, Serres’ painting The Landing could be seen as a performance of British maritime success during a moment of crisis in British imperial identity: the American War of Independence. After the Seven Years’ War eliminated French and Indigenous military threat in the North American colonies, Anglo-Americans began to question the necessity of British military presence.45 Combined with new measures forcing American colonists to bear the financial burden of British Empire (such as the Sugar and Stamp Acts), this insinuation of British control by force fuelled hostility that would lead to revolution. The Landing was painted sometime in the early 1770s, just as this tension was brewing, erupting in events such as the Boston Massacre (1770) and Tea Party (1773). American rebellion was a distinct possibility, and so too was French support for the Americans, as the Earl of Sandwich prophesised: ‘At bottom our inveterate enemies … [are] only waiting for the favourite moment to strike the blow.’46 From this perspective, Serres’ paintings for the Keppel family convolute the chronology of Roach’s surrogative process. Historical victory becomes a surrogate for future victory, projecting British dominance into collective memory. Victories of the Seven Years’ War were decisive moments in conceiving eighteenth-century British imperial identity. Their repetition in art reproduces that identity.

In a letter from 1781, during the American War, historian and Whig politician Horace Walpole wrote that ‘our empire is falling to pieces; we are relapsing to a little island. In that state, men are apt to imagine how great their ancestors have been … The few, that are studious, look into the memorials of past time; nations, like private persons, seek lustre from progenitors.’47 Serres’ painting does exactly that. It looks to memories of imperial achievement as Britain is faced with the potential loss of territory at the hands of its rivals, the French, and subjects, the American colonists. As Douglas Fordham writes, ‘the victories of the Seven Years’ War resounded in English hearts for decades to come as a nearly mythic period of national unity and communal triumph.’48 This variety of performance is not unique to Serres. In 1739, the same year of British victory over the Spanish in the Battle of Portobello, the English engraver John Pine published a series of engravings of tapestries depicting the defeat of the Spanish Armada (Fig. 7). Contemporary victory is contextualised and performed in respect to historical victory.49 Indeed, Eleanor Hughes remarks that the Armada episode served as a ‘touchstone into the nineteenth century’ for the portrayal of British maritime success, reinforcing the repeated performance of imperial power in reference to historical memory.50 As the performance theorist Herbert Blau states, ‘Where memory is, theatre is.’51 Each representation is a re-enactment of what came before, creating what Roach terms a ‘genealogy of performance.’52

Ships, I have contended, symbolically perform the essence of Britain’s imperial-maritime identity, becoming the protagonists of Serres’ The Landing. Centrally placed and lovingly detailed, they emerge into view from shafts of light and dusky pink skies in the right background, recalling Garrick’s sentimental lines in Hearts of Oak: ‘Britannia triumphant, her ships sweep the sea.’53 Yet the ship’s symbolic position in the collective memory of Britannia triumphant obscures a darker purpose of the ship. In 1713, the Spanish awarded Britain the asiento, the right to procure slaves for colonies in South America. By the 1730s, British traders had established their dominance on the African Coast as the supreme slaving nation. This history evokes the ship of the Middle Passage: the ship of the infamous 1789 Brooks print—a diagrammatic representation of enslaved Africans crammed into a slaving ship, distributed by abolitionist groups in Britain. Serres’ performance of Britannia’s magnificent fleet born out of almost providential light feels jarringly displaced from the ship of Britain’s slave trade.

However, The Landing still evokes the memory of the transatlantic slave trade in the figures of enslaved Black workers on the shoreline (Fig. 8). These individuals are referenced in an account of the Siege of Havana published in the London Chronicle on 14 September 1762.54 The account records that 30 June was taken up in carrying ammunition and necessities ashore, a task performed both by the soldiers and by ‘500 blacks purchased by Lord Albemarle at Martinico and Antigua, for that purpose.’55 This group of Black men, labouring in the shadow of Britannia’s symbolic fleet, recalls the memory not only of the 500 enslaved individuals purchased by Lord Albemarle, but the 3.4 million Africans trafficked across the Atlantic in British ships between 1640 and 1807. The symbolic ship of Britain’s eighteenth-century imperial-maritime identity thus merges with English sociologist Paul Gilroy’s metaphor of the ship as representative of the Middle Passage and the circulation of Black diasporic cultures around the Atlantic.56 In 1785, as quoted above, John Campbell alluded to the ‘flourishing plantations’ that were indebted to ‘naval strength.’ However, the strength of Britain’s plantation system stood in debt to millions of enslaved labourers. In the same breath, Campbell categorises plantations with British freedom, with almost unbearable irony. The lack of specifics in the invocation of ‘naval strength’ and ‘flourishing plantations’ allows for euphemistic surrogation. Visions of righteous British greatness obscure Britain’s complacent participation in systems of exploitation and abuse, in a performance that would be re-enacted for centuries to come.

Yet, as Roach writes, ‘because collective memory works selectively, imaginatively, and often perversely, surrogation rarely if ever succeeds.’ Memories of slave ships and the trade they facilitated are irrevocably intertwined with The Landing’s performance of maritime imperialism: memories that cannot be entirely erased, only imperfectly veiled and left at the edges of historical retellings. The Landing illustrates the unsuccessful nature of surrogation, as described by Roach. Righteously triumphant, Britannia, symbolised by the ship in the centre, competes with memories of the slave trade. The anonymity of the labourers competes uneasily with personalised accounts such as James Miller’s, and with the reality of the sailor not as a ‘robotic heart of oak’ but as a multifaceted, defiantly heterogeneous labour force. Ultimately, the ideal of a stable British Empire in the Atlantic Ocean would compete with the loss of the North American colonies, revealing that ‘empire could be vulnerable,’ and exposing a teetering struggle to maintain imperial territories.57 American independence, Douglas Fordham writes, ‘shattered Britain’s imperial confidence’ and precipitated a shift eastward in imperial focus.58

These examples of imperfect surrogation within the painting mirror Serres’ own experience and the imperfect surrogation on which his identity was constructed. As a French man working in a British context, his existence entailed acts of double consciousness. Serres was the sole marine painter in the Royal Academy and was appointed as official Marine Painter to King George III in 1780.59 However, Serres himself was distinctly not British. Born in Southwest France, he first arrived in England around 1745 as a French prisoner of war, and spent time either in Marshalsea or Northampshire prison.60 Later, he consciously abandoned his French background and assimilated into British society. Serres’ art, and hence his name, were emblematic of overt manifestations of British naval victory, specifically over the French during the Seven Years’ War. His compositions actively perform British imperial-maritime identity, a performance made uneasy by the reality of his French origin—particularly sensitive at a time when Britain and France were in a prolonged period of formal hostility. One wonders whether Serres himself felt an unreconciled tension between his French nationality and the British nationalism he portrayed in his marine scenes. Despite his long career in England and his involvement in the founding of the Royal Academy, Serres remained in a liminal space between the two countries. Sarah Monks writes that he was not French enough for the French, failing to secure a commission from the Maréchal de France for paintings of French naval victories during the American War of Independence, yet was simultaneously too French for the British.61 Along with Johan Zoffany, Benjamin West, and Philip James de Loutherbourg, Serres was cited in complaints that the Academy gave preference to foreign talent over native British artists.62 Arguably, such split identities are characteristic of the eighteenth-century Atlantic World, which blurred physical and conceptual boundaries of identity, as European nations colonised lands around the Atlantic Ocean, and new diaspora sprung up around its perimeter. For instance, settlers and their descendants in settler colonial states like Canada and Ireland created new identities to cultivate a sense of belonging. No longer identifying with the colonial metropole—Britain, for example—yet not truly native to their colonised home, they performed indigeneity through calibrated cultural self-representation, which often plucked from Indigenous cultures. For example, Anglo-Irish settlers adopted the Gaelic Irish symbol of the ancient harp for their own imagery. Comparable to Serres’ oscillation between French and British, settlers occupied a wavering space between belonging and unbelonging.

Like Serres, the genre of maritime painting performed Britishness. While it came to be seen as an appropriate conduit for visualisations of British naval strength, the genre itself was an export from the Netherlands. Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom, born in Haarlem around 1566, has been hailed as the ‘real founding father of marine painting.’63 During the third Dutch War (1672-1674) King Charles II encouraged Dutch subjects to settle in England.64 Willem van de Velde and his son arrived in London and re-established the genre of maritime painting in Britain in the seventeenth century. Over the next hundred years, marine painters in Britain continued to utilise the Dutch devices of isometric perspective, expansive view, and low horizon, such as can be seen in Serres’ The Landing. This myth of British nationhood is therefore performed in a borrowed and adopted system of representation. Similarly, the conception of nationhood itself is not intrinsic or fundamental, but weaved together in various threads of borrowed traditions, retold fables, and over emphasised singularities.

The Atlantic World is also a confluence of migrated traditions and identities shaped by cross-cultural interactions. The emergence of the Atlantic World during the early modern period entailed a disruptive domino effect whereby a new world order and way of thinking gradually replaced the standards and identities of the Middle Ages. Britain matured as an imperial-maritime nation in this setting. British imperial-maritime identity depended for its existence on reiterated performances of naval strength and patriotic unity, as exemplified in Serres’ The Landing. Veils were drawn over the unpalatable, the inconvenient, and the ignoble. Yet Serres’ painting, and the context of its creation, proves the translucency of these veils. Even in such an outward expression of imperial prowess, undesirable realities bleed through—maybe hidden in shadows behind Britannia’s monumental fleet, but obstinately refusing obscurity and negation. Memory, as Roach writes, retains its consequences, and the ‘unspeakable cannot be rendered forever inexpressible: the most persistent mode of forgetting is memory imperfectly deferred.’65

Citations

[1] ‘A Song on the Conquest of the Havannah,’ London Evening Post, 12 October 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection.

[2] ‘News,’ Lloyd’s Evening Post, 10 September 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection.

[3] David Garrick, Hearts of Oak, allpoetry. com.

[4] Joseph R. Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), 122.

[5] Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance, 3.

[6] Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance, 3.

[7] Geoff Quilley, Empire to Nation: Art, History and the Visualization of Maritime Britain, 1768-1829(New Haven: The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press, 2011); Esther Chadwick, ‘Portraiture in Indigenous London: Mohawks at the British Museum in 1776,’ American Art36, no. 2 (June 1, 2022): 20–26.

[8] Hammad Nasar, ‘South Asia, and the Possibility of Co-Habitation,’ Take on Art, South Asia, 10, (2023), 30.

[9] ‘The Capture of Havana, 1762: the Landing, 7th June,’ Royal Greenwich Museums, online.

[10] ‘The Capture of Havana, 1762: the Landing, 7th June,’ Royal Greenwich Museums.

[11] Alan Russett, Dominic Serres, R.A., 1719-1793: War Artist to the Navy (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2001), 33.

[12] ‘The Capture of Havana, 1762: the Landing, 7th June,’ Royal Greenwich Museums.

[13] Douglas Fordham, British Art and the Seven Years’ War: Allegiance and Autonomy (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 4. For discussion of Britain’s fiscal-military state, see John Brewer, The Sinews of Power: War, Money and the English State 1688-1783 (Boston: Harvard University Press, 1990).

[14] Russet, Dominic Serres, R.A., 1719-1793: War Artist to the Navy, 21.

[15] Russet, Dominic Serres, R.A., 1719-1793: War Artist to the Navy, 22.

[16] Russet, Dominic Serres, R.A., 1719-1793: War Artist to the Navy, 23.

[17] Sarah Monks, ‘Our Man in Havana: Representation and Reputation in Lieutenant Philip Orsbridge’s Britannia’s Triumph,’ in Conflicting Visions: War and Visual Culture 1600-1850 (Oxford: Taylor and Francis, 2005), 92.

[18] The Public Advertiser, 21 May 1765, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection.

[19] ‘The Capture of Havana, 1762: the Landing, 7th June,’ Royal Greenwich Museums, online.

[20] Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance, 3.

[21] E Archibald, ‘The Willem Van De Veldes, Their Background and Influence on Maritime Painting in England,’ in Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 130, no. 5310 (1982).

[22] Frans De Bruyn and Shaun Regan, ‘Introduction,’ in The Culture of the Seven Years’ War: Empire, Identity, and the Arts in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014), 3.

[23] For an account of this reading of British Empire, see, for example, David Armitage, The Ideological Origins of the British Empire, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 2. Such a reading suggests that this ‘First’ Atlantic-centric empire gave way to a ‘Second’ empire focussed eastwards towards the Indian and Pacific Oceans in the late eighteenth century. Yet, as David Armitage contradicts, these empires overlapped and their ideological basis was shared.

[24] Armitage, The Ideological Origins of British Empire, 8.

[25] Armitage, The Ideological Origins of British Empire, 15.

[26] John Campbell, Lives of the British Admirals: Containing a New and Accurate Naval History, from the Earliest Periods; with a Continuation Down to the Year 1779 (London: Printed for G. G. J. and J. Robinsons, 1785), ed. by John Berkenhout, (1779), 81.

[27] Monks, ‘Our Man in Havana: Representation and Reputation in Lieutenant Philip Orsbridge’s Britannia’s Triumph,’ 90.

[28] Marcus Rediker and Peter Linebaugh, Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: Merchant Seamen, Pirates and the Anglo-American Maritime World, 1700-1750, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

[29] Peter Way, ‘Rebellion of the Regulars: Working Soldiers and the Mutiny of 1763-1764,’ The William and Mary Quarterly 57, no. 4 (2000), 770; Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic, (Boston: Beacon Press, 2013), 150.

[30] Sayera Irfan Habib, ‘Colonial Exploitation and Capital Formation in England in the Early Stages of the Industrial Revolution,’ Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 36 (1975), 25.

[31] Way, ‘Rebellion of the Regulars: Working Soldiers and the Mutiny of 1763-1764,’ 776.

[32] Way, ‘Rebellion of the Regulars: Working Soldiers and the Mutiny of 1763-1764,’ 775.

[33] Way, ‘Rebellion of the Regulars: Working Soldiers and the Mutiny of 1763-1764,’ 775.

[34] Way, ‘Rebellion of the Regulars: Working Soldiers and the Mutiny of 1763-1764,’ 775.

[35] Way, ‘Rebellion of the Regulars: Working Soldiers and the Mutiny of 1763-1764,’ 775.

[36] Way, ‘Rebellion of the Regulars: Working Soldiers and the Mutiny of 1763-1764,’ 773-5.

[37] Linebaugh and Rediker, Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: Merchant Seamen, Pirates and the Anglo-American Maritime World, 1700-1750, 168.

[38] Quilley, ‘The Image of the Sailor,’ in Empire to Nation, 168.

[39] Quilley, ‘The Image of the Sailor,’ in Empire to Nation, 181.

[40] ‘A Sailor’s Letter from the Havannah,’ London Daily Advertiser, 23 October 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection.

[41] Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance, 3.

[42] ‘A Sailor’s Letter from the Havannah,’ London Daily Advertiser, 23 October 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, online.

[43] Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance, 3.

[44] David Garrick, Hearts of Oak, allpoetry. com.

[45] Thomas Benjamin, The Atlantic World: Europeans, Africans, Indians and Their Shared History, 1400–1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 504.

[46] Benjamin, The Atlantic World, 505.

[47] John Bonehill and Geoff Quilley, Conflicting Visions: War and Visual Culture in Britain and France, c. 1700-1830. (Oxford: Taylor and Francis, 2005), 8.

[48] Fordham, British Art and the Seven Years’ War, 5.

[49] Eleanor Hughes, Spreading Canvas: Eighteenth-Century British Marine Painting, (New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 2016), 5.

[50] Hughes, Spreading Canvas, 5.

[51] Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance, 4.

[52] Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance, 20.

[53] David Garrick, Hearts of Oak.

[54] ‘Journal of the Siege of Havana,’ London Chronicle, 11-14 September 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection.

[55] ‘Journal of the Siege of Havana.’

[56] Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, (Boston: Harvard University Press, 1993).

[57] Peter Frankopan, The Silk Roads, (London: Bloomsbury Publishing 2015), 280.

[58] Fordham, British Art and the Seven Years’ War, 22.

[59] Russet, Dominic Serres, R.A., 1719-1793: War Artist to the Navy, 10.

[60] Russet, Dominic Serres, R.A., 1719-1793: War Artist to the Navy, 14.

[61] Monks, ‘Our Man in Havana: Representation and Reputation in Lieutenant Philip Orsbridge’s Britannia’s Triumph,’ 68.

[62] Monks, ‘Our Man in Havana: Representation and Reputation in Lieutenant Philip Orsbridge’s Britannia’s Triumph,’ 68.

[63] Archibald, ‘The Willem Van De Veldes, Their Background and Influence on Maritime Painting in England,’ 347.

[64] Archibald, ‘The Willem Van De Veldes, Their Background and Influence on Maritime Painting in England,’ 354.

[65] Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Visual Culture, 4.