This essay explores novelist, poet, critic, and doodler Stevie Smith’s disruption of conventional distinctions between the textual and the material in her first book, Novel on Yellow Paper (1936). Taking the yellow copy paper of its title as a starting point, I propose that Smith problematises the relationship between her typescript and the published novel in order to suggest that the publishing industry is a source of textual corruption, that texts do not necessarily speak with the unified voice that a page of uniform type implies, and that appreciating the intricacies of a text’s genesis enables readers to think critically about their own susceptibility to textual influence.

I am typing this book on yellow paper. It is very yellow paper, and it is this very yellow paper because often sometimes I am typing it in my room at my office, and the paper I use for Sir Phoebus’s letters is blue paper with his name across the corner ‘Sir Phoebus Ullwater, Bt. ’[…] And that is why I type yellow.[1]

This is how Stevie Smith sets up the underlying premise of her 1936 debut novel, Novel on Yellow Paper, or: Work It Out for Yourself. The novel recounts the life of her protagonist, Pompey Casmillus, and her ongoing experiences as private secretary to a publishing magnate in the years preceding Britain’s entry into the Second World War. It is a first-person plunge into Pompey’s inner world as she navigates London society, the inner workings of the publishing world, sexual politics, Europe, antisemitism and two failed love affairs. As she tells her readers in this extract, Pompey’s exploits and meandering reflections on her life are typed up during her work hours on cheaper, yellow carbon copy paper taken from her office.

In this sense the novel is, at minimum, semi-autobiographical: Smith was also a private secretary to publishing magnate Sir Neville Pearson, and the book’s title began as an intermediary descriptor adopted by the staff at her publishers, Jonathan Cape, to identify Smith’s yellow typescript after her original title, Pompey Casmillus, was felt to be unsuitable. The only amendment made was to add ‘… or: Work it Out for Yourself’, an adjunct that has gradually disappeared from the covers of modern editions. Nevertheless, the full title reiterates the book’s refusal to settle into a conclusive form. Smith’s adoption of this intermediate descriptor as a title exposes the perplexing fluctuation of the book’s form, and the ‘it’ of ‘Work it out for Yourself’ demands a material as much as a literary hermeneutic response.

This essay approaches the riddle posed by Smith’s title by first exploring the significance of yellow paper. I do this by comparing Smith’s novel to other yellow books, most notably Aubrey Beardsley’s Yellow Book that the title invokes.[2] Where Smith’s book differs from previous yellow books is that the material qualities being emphasised as she reflexively references the ‘typing’ process are absent in the book encountered by the reader. This instability is felt most keenly in the absence of yellow paper from published editions. In this way, Smith undermines the book being read: although the novel appears self-reflexive, we are always aware that it is not our version that the speaker is creating but rather one of multiple typescripts that may or may not exist. Using Nelson Goodman’s notion of the autographic and allographic as a theoretical framework, in combination with Barthes thinking on the nature of Cy Twombly’s asemic writing, I will argue that Smith uses Novel on Yellow Paper to disrupt conventional distinctions between art and text, the handwritten and the typed, and their relationship to the body. By rendering an originating yellow typescript a ghost text that haunts the published novel, she implores us to question the other ghosts of secretaries and commercial interests whose voices are cloaked within the uniformity of a printed text.

Yellow Books

Whether the ‘Yellow’ of the title was arrived at inadvertently or not, it positions the novel as participating in a legacy of provocative books, mostly occurring in the second half of the nineteenth century, whose colour in each instance became synonymous with their reputation in terms of content, price or aesthetics. Beginning in the 1850s, ‘yellowback’ referred to a new genre of cheap novels sold in Britain. Meanwhile, French bookshops both identified and concealed their more salacious offerings by wrapping them in yellow paper.[3] Inspired by this phenomenon, it is a yellow book to which Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray attributes his corruption.[4] Finally, there was the literary quarterly The Yellow Book that ran from 1894 to 1897, which Wilde was (incorrectly) rumoured to be carrying on his arrest.[5] In the case of these books, yellow is used to signal in multiple, sometimes contradictory, directions. In the French context, yellow implies both the power of literature to corrupt and its opposite in the efficacy of literary censorship. On the other hand, the colour of the cheaply produced yellowback announced its democratising affordability in contrast to the luxury of The Yellow Book. These are themes that recur throughout Smith’s novel, suggesting her title was more than just serendipitous. On a train in Germany, Pompey reads an intact edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover whose erotic content rendered it illegal in the United Kingdom until 1960.[6] Elsewhere, she satirises cheap publications, particularly for the advertisements that make them financially viable at such low cost.

However, it is the contrast between the material reflexivity of Novel on Yellow Paper and the prospectus that prefaced the first edition of The Yellow Book that is particularly illuminating. The ‘prospectus’ to the Yellow Book was an eight-page document which set out the publishers’ and editors’ hopes for the publication, with a particular emphasis on the material qualities that it already exemplified. It declared that The Yellow Book was to be ‘beautiful as a piece of bookmaking’, from its hard-back cover (rare for a magazine) to its iconic binding and, most pertinently, ‘the size and shape of the paper (now being especially woven) on which it will be printed, as well as the type that will be used, and the proportion of text and margin’.[7] The lavish appearance of The Yellow Book, which was bound in ‘limp yellow cloth’ and printed with the illustrations of its art editor Audrey Beardsley (1894-1897, Fig. 1),[8] gained it a reputation as the epitome of fin de siècle decadence.[9] Underlying the similarity in their titles is the conceit of a book that is aware of its own materiality. The link is an ironic one: whereas The Yellow Book embodied an aesthetic of ostentatious luxury, Smith’s yellow paper is cheap office paper and signals the financial limitations of its author. More fundamentally, The Yellow Book delivers on the quality of the paper it describes whereas Novel on Yellow Paper never could. Indeed, as it was her first novel, and had already been rejected by Chatto and Windus prior to being accepted by Jonathan Cape, we can speculate that Smith would have typed it knowing that it would not be commercially viable to incur the additional expense of producing a facsimile. Consequently, the published edition of Novel on Yellow Paper actually does resemble The Yellow Book by virtue of its white pages and the displacement of yellow onto its covering (1936, Fig. 2).

Whilst in practice, the decision to displace yellow onto the book’s cover only emphasises its bleached pages, it is also indicative of the habitual dialectic between the visual, material significance of a book cover and its incorporeal contents. Any book that has the good fortune to be pronounced a ‘classic’ will subsequently be available in a plethora of covers for consumers to choose from. The choice of cover relates more to the consumer’s idea of themselves as a reader and their personal connection to the book. The book becomes a personal object marked by the ongoing interaction between it and the body of its reader. Consequently, in The Yellow Book’s prospectus, ‘book-lover’ comes to mean a love of the object rather than a metonym for reading.[10] Indeed, Oscar Wilde depicts Dorian Gray obtaining multiple copies of the unidentified yellow book gifted to him by his corrupt mentor in different bindings to suit his different moods, whilst the pages within remain identical, as a symbol of Dorian’s appropriation of its debauched ethos.[11] The fluctuation of the outer cover is accepted, not as an alteration of the book, but a change in the reader. We assume that the page never really changes. Smith’s insistence on the material qualities of her page, rather than its outward covering, disrupts this convention. This distances her from the history of previous yellow books, but more importantly it distances her typescript from the published edition.

Autographs and the Autographic

In Languages of Art, Nelson Goodman proposes a distinction between the ‘autographic’: works such as paintings whereby ‘even the most exact duplication of it does not thereby count as genuine’, and the allographic: predominantly musical or literary works that only require the correct sequence of letters or notes to be legitimate and therefore can be infinitely reproduced without becoming forgeries.[12] In the latter instances, components that need to be reproduced exactly for a work to be authentic, like spelling, are ‘constitutive’; otherwise, features like the material a book is printed on are ‘contingent’.[13]

The prevalence of e-readers and digitised documents confirms that his view has, generally, been accepted. Even if there have been concerns about the threat posed to bookshops and printing presses, it is not the validity of digital publications that is in question. In Bonnie Mak’s How the Page Matters, she suggests that the fluctuation of formats in which texts are made available has not been sufficiently examined:

[…] despite its central role in the transmission of thought, the page often passes without registration or remark. So habituated are we to its operation, we often overlook how the page sets the parameters for our engagement with ideas.[14]

Mak traces the significance of the page by analysing the differing formats in which the same text, Controversia de Nobilitate, has been published, from fifteenth-century manuscript to digital translation. Smith’s invocation of yellow office paper does not allow for such fluctuation. Instead, she suggests the centrality of the page by fixing it as an unalterable and inimitable ideal. Smith articulates a supposedly contingent characteristic – the paper her novel is printed on – within the constitutive body of the work, thus undermining the authenticity of the edition in the reader’s hand.

As previously mentioned, the ‘yellow paper’ refers to the lower-quality paper used for creating carbon copies.[15] In this way, Smith’s paradigmatic substrate is designed to receive the original’s near but nonetheless degraded imprint, making the notion of the imperfect reproduction paradoxically intrinsic to her inimitable typescript. It is typed on copy paper but cannot truly be copied. By continually drawing attention to the existence of a typescript possessing material properties (and indeed textual properties) that are absent from the print run, Smith suggests that the original typescript is an autographic work and thereby continuously undermines the legitimacy of the printed edition. Peculiarly, Smith’s actual typescript also falls short of the mark: the earliest version, now owned by the University of Hull, is a faded dull brown akin to what you would expect of any aged document (1935-1936, Fig. 3). Although a few pages of the typescript have a brighter, more yellow hue, these pages form part of a later revised version (1935-1936, Fig. 4). Therefore, the continuity of the document that Smith teases her reader with is imagined. Like the author’s relationship to the character of Pompey, the actual typescript’s relationship to the ‘yellow paper’ is not consistently parallel.

This inconsistency could not be remedied by simply procuring a supply of yellow copy paper on which to retype Smith’s first submitted typescript. To start with, procuring such paper would be no mean feat. Confining differences to the realm of printing papers, stationer Harry A. Maddox specifies important differences in ‘colour, texture, finish and strength’ in his book What a Stationer & Printer Ought to Know About Paper. As he puts it, ‘modern printing papers are of so many types and varieties, that familiar knowledge of all the grades is not a common acquisition’.[16] Even having specified the grade and variety of copy-paper, a replica would also need to account for the infinite variations produced by flaws in manufacture, and the creases, tears and imperfections imparted to paper thereon.

The singularity of the paper used to create a work is reflected on by Barthes in his analysis of Cy Twombly’s asemic writing. Barthes notes Twombly’s elision of the semantic function of writing as a means of foregrounding the materiality of the page: ‘No surface, wherever we consider it, is a virgin surface: everything is always, already, rough, discontinuous, unequal, set in motion by some accident’.[17] ‘Accident’ suggests the extent to which even a material like paper, the automated production of which is geared toward absolute uniformity, is nevertheless always shaped by chance regardless of how minute the implications of that accidental variation might be. To view paper as incidental, rather than specific, is a convention that overlooks its potential as a repository for meaning.

Consequently, it is significant that Barthes refers to the ‘paper’ rather than the ‘page’.[18] Once a sheet of paper has been characterised as a ‘page’, a transformation has already been enacted in which it becomes a surface that expects to be marked in a particular way. Hence, lined paper has been printed but is still referred to as ‘blank’. This subtle shift in semantics requires a suspension of disbelief that projects a platonic ideal of the blank surface and relegates its texture and colour to an absence of text. Substituting ‘paper’ for ‘page’ enables Barthes’s reader to recognise its materiality more clearly and thus that it is specific even where mass-production idealises the generic. When Pompey claims to ‘type yellow’, she figuratively subsumes the text’s colour into the page’s colour, inverting the dynamic of the ‘blank’ page and implying that the page itself informs the text and is replete with meaning prior to any type. Indeed, in her essay ‘What Poems are Made of’ Smith declared that ‘colours are what drive me most strongly’.[19] In this case we might speculate that the novel is ‘made of’ the impetus of Smith’s encounters with the ‘very yellow’ of the copy paper even if it was never literally ‘made of’ yellow paper in the way her speaker suggests.

As well as foregrounding the paper’s irreproducibility, Smith’s claim to ‘type yellow’ decentres the printed type in order to place emphasis on the idiosyncratic gesture of typing that created it. Prior to his discussion of paper, Barthes describes Twombly’s asemic writing as preserving ‘the gesture, not the product’ where the gesture is ‘something like the surplus of an action. The action is transitive, it seeks only to provoke an object, a result; the gesture is the indeterminate and inexhaustible total of reasons, pulsons, indolences which surround the action.’[20] Hence, when Smith says she ‘types yellow’, she also expresses a desire for a sort of textual self-abnegation whereby the text is only the evidence of its own creation and her text becomes the indexical trace of a gesture rather than a vector of linguistic meaning.

Barthes goes on to locate the material worth of an artwork in the irreproducibility of the artist’s gesture which, he contends, is derived from the inimitability of the body that creates it.[21] At the intersection between Barthes and Goodman is the idea that an autographic work’s legitimacy lies in the singularity of the body that directly causes its creation, whereas an allographic work does not rely on direct interaction: at its core is the reproducible action and not the surrounding gesture. In terms of Novel on Yellow Paper, this means that arguing for the irreproducible centrality of the original typescript, irrespective of whether its words match the published book, essentially relies on the notion that typing can be thought of as gestural.

In order to underline the significance of gesture, Smith takes the reader through multiple examples whereby gesture disrupts conventional notions of authenticity. She describes a schoolteacher who taught Pompey’s mother and aunt to paint by copying famous artworks but would ‘put in the difficult bits’ himself.[22] Pompey dwells on the injustice that the canvases only bore the signature of the pupil and not the teacher, lamenting that he has ‘nothing to show for it all, just stifling anonymity’.[23] The artist whose work they have copied is notably unmentioned, an omission that points to the idea that in painting, ‘copying’ is never truly copying. The gesture embedded in the original is irreproducible and therefore, in gestural terms, the copied work is entirely original. Paintings are deemed to be saturated by the artist’s body throughout, their bodily relation to its creation is conceivably (if not currently) detectible in every brushstroke.[24]

Concurrently, the existence of signatures at the bottom of otherwise typed text is a recognition that a bodily interaction with the text is required to activate it. Indeed, the signature’s legitimacy does not reside in its legibility at all; the large gestural loops that are practically convention frequently lean toward the asemic. In other words, the requirement of a signature invests a document with the parameters of an autographic work. Handwritten texts are imbued with the presence of their author so that the text is a sort of external secondary body: a carbon copy of intent. The prime example of this is the passport or identification card, which must be signed to activate its authority. We might also consider Picasso’s refusal to sign one of his earlier works on the grounds that ‘I’d be putting my 1943 signature on a canvas from 1922’.[25] His comment is indicative of the way that the signature is bound to the body and preserves its agency at a particular moment in time. Even works created by the same person at different intervals are composite traces of a body that becomes other, even to its former self, throughout time. Hence the authority of a signature divests the signee of the agency to retract that decision. Taken to its to its extreme, this line of thinking means that even a writer’s revision of their own work is an encroachment.

As well as the immediate material qualities that a reader holding Novel on Yellow Paper can observe, the disjunction between the yellow typescript and published book is more subtly manifested in the differences between the temporality of the typescript’s creation and its printed reproduction. For example, when the speaker complains that ‘There never was anyone so tired as poor Pompey at this moment at this page, at this very line, at this word’, the reflexivity of ‘at this moment’ fails for Novel on Yellow Paper because it relies on the bodily trace of the author which has been erased by the printing process.[26] The body that is ‘tired’ is the body that is typing, and it is only in relation to that body that the line, page and word become the displaced location of this fatigue. ‘This’ refers to the specific temporality of the typescript’s creation, which is transferred to the temporality of the reader who processes words, if not at the same pace as the typist composes them, then at least in the same order. This is a connection from which the published edition is alienated not only by the physical absence of the author at the printing press but by its altered temporality. Unlike a typewriter that immediately prints the letters as they are typed, creating a correspondence between the sequence of printing and the sequential movement of the body moving across the keyboard, the printing press produces pages instantaneously as full blocks of text.

In Pompey’s case, her ‘tearful’ reaction to the schoolteacher’s anonymity arises from her own misgivings about the ghost-writing that she undertakes on Sir Phoebus’s behalf.[27] Indeed, comparison with copied paintings suggests that even the erasure of a typist from dictated correspondence or the conversion of an author’s manuscript into type is a form of misrepresentation. This fraught relationship is apparent in Pompey’s proliferation of secretarial aliases:

Signing my letters: Private Secretary […] Signing my letters: Charity Publicity. Signing my letters: Reader, for Editorial Manager. Signing my letters: Phoebus Ullwater tout court, without the hedging chivvying in valiant p.p. Phoebus Ullwater, in slanting ruffling swashbuckling forgery. Forgery.[28]

The flippancy with which Pompey switches between signatures in her secretarial work points to an erasure of her creative agency from textual production. Her admission of omitting the ‘p.p.’ (per procurationem or, translated, by proxy) begs the question of whether the condemnation attached to the idea of ‘forgery’ ought to attach itself to the secretary who signs in her boss’s name or the boss who consequently takes credit for her prose as his own. Furthermore, the variation of her signature – even when it is not deceptive – renders it meaningless, detached from the singularity of the body that created it. This feeling is exacerbated by the knowledge that these letters are written on the ‘blue paper with [Sir Phoebus’s] name across the corner’. We are presented with three forms of signature embodying varying degrees of gesture: the ‘slanting ruffling’ handwritten signature, the typed signature (‘Private Secretary’) and the name pre-printed on the edges of stationery. Ordinarily, according to the logic of the autographic, one might expect the three forms to degrade in authenticity respectively. However, because the printed and handwritten variations give the name of her employer as the document’s creator, it is the typed iteration which emerges the most legitimate. Indeed, given that the novel begins with the poetic declaration ‘Casmilus, whose great name I steal, /Whose name a greater doth conceal’,[29] and therefore that Pompey’s name is a pseudonym, her role as a ‘private secretary’ is the most stable facet of Pompey’s identity, both within the novel and in relation to Smith, that she could sign with. As a signature which results from the gestural action of an individual body (as I will go on to explain) but whose typed product is visually generic, repeatable across offices and typewriters to the point of anonymity, it embodies the contradiction of the ghost-writer.

Ghosts

As has been alluded to, the direct relationship between the body of the author and her text is particularly fraught for Smith and her double, Pompey, because their typewriter is also the apparatus of their secretarial work. Critics such as Leah Price have pointed out that the identity of the typist was often collapsed with that of her machine so that initially, ‘typewriter’ referred both to the machine and its operator.[30] Though this was no longer the case by the twentieth century, the underlying ideal of the typist whose automated efficiency causes her to be like an extension of her machine persisted, as Smith alludes to with ‘Sir I Name no Names’ whose prolific writing of letters has ‘worn down’ several secretaries as though they were a stationery supply. [31] In a paper delivered in 1917, Constance Hoster of ‘Mrs Hoster’s Secretarial School’ at which Smith trained, declared that it was ‘by efficiency that [women] can hope to prove our value in the world of work’, a trait that she advises can only be acquired through training.[32]

Smith resists this ‘efficiency’ and its concomitant attribute, accuracy, because they amount to suppression of gesture and its foundation in the ‘surplus’ of action described by Barthes.[33] The ‘ten-finger method’ taught in secretarial schools aimed to increase efficiency by having typists memorise the keyboard and minimise overall movement by assigning each finger part of the keyboard.[34] It replaces the conscious effort of finding a letter on the keyboard with a standardised system repeated until it becomes muscle memory and is measurable by a metric of words per minute. In contrast, Pompey’s technique of ‘not being able to type with more than one finger on each hand’ necessitates each finger traversing across half the keyboard as she types.[35] The gesture of her typing is spontaneous in the sense that it is disorganised, but it is also clearly a conscious choice to keep it so (especially if we assume that Pompey, like Smith, had been trained). She affects the halting type of an untrained secretary in order to assert the gestural influence of the fallible body. On the surface, this faux-incompetence seems to show a disregard for sophistication, but this is undermined by the specific power dynamics inherent in typing. The typist that manages 150 words per minute can do so because she is not involved in their composition. Refusing to utilise her skill undermines her suitability as the amanuensis so that she can inhabit the role of author.

Another way in which Smith humanises her typing is by the inclusion of errors. Victoria Olwell describes how the ‘cloak of invisibility covering the body in the text drops away […] the moment that body makes a mistake’, reminding us that the typewritten document is open to the random errors of a finger that slips, or mind that wanders, in a way that a machine is not.[36]However, Pompey’s errors are slightly more complex. The typescripts do suggest that Smith was a sloppy typist, but these unconscious errors are annotated and corrected. Instead, the spelling errors that are included are those that are not the product of accident but of deliberate ignorance, particularly with regard to the spelling of names. Consequently, when Romana Huk alleges that the misspelling of Halliburton as ‘Mrs Haliburton’s Troubles’ and the roman Camillus as ‘Casmilus’ signals ‘the erosion and perpetuated corruption of texts’, she is, in a sense, correct, but she also echoes the voices of those who see the pinnacle of a typist’s skill to be invisible, a ‘ghost-writer’ of other people’s work.[37] What she fails to recognise is that the very fact that texts are open to this form of corruption is a way of asserting the creative agency of the typist and of further protesting the attribution of a text’s creation to a singular named author. Why should the unnamed typist care to be pedantic about the names of others? Confusingly, Huk asserts that ‘inaccuracies’ such as these foreground the ‘text as text’ (as opposed, one infers, to speech).[38] I would argue that a more accurate description would be that Smith foregrounds the text as type and thereby foregrounds the body of the typist, undercutting quasi-mystical claims to the superiority of the handwritten manuscript that arose in reaction to the spread of typewriters.[39]

Alongside Smith’s deliberate incorporation of Pompey errors, is a genuine resistance to the interference of editors. This is tacitly affected in Pompey’s spelling mistakes, but explicitly declared at points where editorial amendments (real or not) have been conceded. For example, Pompey refuses to elaborate upon ‘cash instalments’ because her publishers, protecting their relationship with advertisers, would object. Instead, she declares: ‘There’s just one word that covers that, and that is delete.’[40]

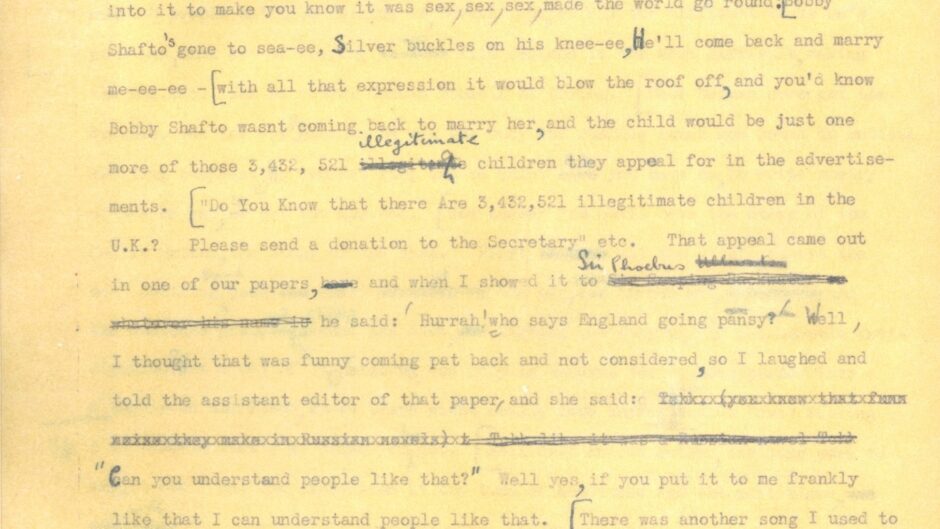

Further to the insistent presence of possible alternative typescripts is the notion that they can never truly be erased and therefore restoring the body of the ghost-writer is accompanied by a restoration of the spectral text that denotes an author’s fallibility: the draft. This relies on an understanding that ‘deletion’ in the sense that we understand it now, whereby the typed text of a word processor can be erased without trace, is not possible for works composed on a typewriter. Instead, Smith’s typescripts either type over the mistake with a line of ‘x’s or they are drawn over in pen (1935-1936, Fig.4). Therefore, ‘delete’ points apophatically to the existence of an intact document which has presumably been annotated by hand to indicate the removal of the offending phrase in its next iteration. Although we cannot rule out the possibility of this existing in a previous typescript, the typescript that is available to us shows no sign of such a deletion (1935-1936, Fig.5). Most likely, her use of paralipsis at this juncture is an affectation of faux-discretion, but this does not rule out genuine censorship elsewhere.

Contributing to this feeling of censorship is the likelihood that alterations required by editors were understood, both by Smith and her readers, as a greater intervention than they would be today. Drafting, redrafting and editing are now taken for granted as an integral component of writing for any serious author (or student), but, as Hannah Sullivan explains in The Work of Revision, it is a practice that only took off during the twentieth century among modernist writers newly supplied with cheaper paper.[41] It is in this context, where the extensive revision of texts is still a relative novelty rather than a given, that Smith is writing. Smith highlights the double standard that occurs when the bodies standing in the way of an author and unfettered communication with their reader are those of publishers, to whom an unknown author is financially and professionally beholden, rather than their scribes, amanuenses or typists. Smith objects to the presumption that the variation produced by editors should be tacitly accepted where those of the latter, and their secretarial successors, are not.

Furthermore, Sullivan contends that ‘textual instability’ between editions of works was newly welcomed as a process of authorial refinement, having ‘traditionally been the unfortunate result of corruption or interpolation during the course of transmission by errant scribes or copyists’.[42] In her analysis of authors like Henry James, who continued revising their work, Sullivan asks, ‘why publish a text before its genesis is complete?’.[43] Smith gives the impression that Novel on Yellow Paper’s publication represents the inverse: a degeneration from the completeness of her original typescript. The gesture of her first typescript cannot be recreated, and therefore the published text is a sort of postlapsarian remnant whose potential lies not at the ‘chaos of genesis’, like a novel that is open to infinite reworking, but somewhere along a confined spectrum of the text’s previous iterations between her first draft and the published novel. Nevertheless, within this confined spectrum exist infinite permutations of previous drafts depending on what, if any, degree of revision or editorial intervention is deemed acceptable. Sullivan has described how ‘a published text’s ‘authority’ evaporates in the face of subsequent authorial revision’; Smith’s achievement is to undermine its authority without ever providing a stable alternative.[44]

This is especially the case given Smith’s opening description of the book as ‘the talking voice that runs on’. Pompey’s meaning is clarified a few pages later, when she expresses concern for ‘this dangerous way I am running on. I am a private secretary’, positioning the ‘voice’ in opposition to censorship, formality, professionalism, and the pauses in which restraint is exercised. [45] At the same time, her insistence on ‘voice’ rather than thought also places the book in opposition to the ‘stream of consciousness’, a descriptor popularised by literary critics to label modernist writers’ attempts to replicate the disorder of unuttered thought.[46] On the surface, Smith’s non-conventional punctuation (or rather its absence) and chaotic manner of flitting between Pompey’s present experiences, memories, and tangential ramblings, invite just such a label and if it were not for Smith’s tautological insistence on speech, the distinction between stream of consciousness and her ‘talking voice’ might easily go overlooked.

Instead, Smith reminds us from the outset that Pompey’s voice is not pre-speech or unuttered; there is no omniscient narrator, and therefore the novel takes place in the world of deliberate, externalised communication. Smith is clear that absence of punctuation is integral to the ‘running on’ of the ‘talking voice’, and hence the addition of punctuation at her publisher’s directive is compared to holding the ‘talking voice […] alive in captivity’.[47] Punctuation is added to make the text more ‘readable’, both in the sense of understanding – by breaking it into units of meaning – but also in the sense of reading aloud. Punctuation instructs the would-be reader on where to breathe. Without it, Smith exerts control over the role of speaker, typist and reader; she is able to occupy the first two, both dictator and amanuensis, while refusing to give the reader the instructions to repeat her words back to her. Consequently, the imposition of punctuation signals a divestment of control not only to the publishers, but to the bodies of the readers who can now vocally appropriate her text. Of course, that is not to say that the text was un-readable prior to its punctuation, but rather that the possibilities of its voice and the way in which it will be read are substantially narrowed and the amorphous ‘talking voice’ is funnelled into Smith’s particular reading. The interfering voices of publishers foists the myth of the singular authorial voice on a text whose purpose was to expose its own multiplicity.

Typography and the Typological

Consequently, when Smith deliberately allows her text to be invaded by the voices of other textual forms, it is a subversively self-aware surrender to the publishing industry. This is apparent in her descriptions of the readers of ‘twopenny weeklies’:

They put a spot of scent behind the ear, they encourage their young men to talk about football, they are Good Listeners, they are Good Pals, they are Feminine, they Let him Know they Sew their own Frocks, they sometimes even go so far as to Pay Attention To Personal Hygiene.[48]

Capitalising these glib descriptors of their readers’ femininity evokes the mise-en-page appearance of the magazine headlines that aim to inculcate these behaviours. Woman’s Own is potentially the magazine Smith had in mind in this passage: it was published by Newnes Publishing, at which Neville Pearson, Smith’s employer, worked. Furthermore, as Greenfield and Reid have shown, the ‘formulaic structure’ of Woman’s Own ‘blurred the distinction between editorials and articles and commercial messages in its drive to engineer consumption’.[49] This ‘formulaic structure’ of the magazine’s appeal to archetypal gender roles is exactly what Smith relies on to enable the reader’s recognition of the form. Alongside the trite wording of these snippets, a subtler mimesis at play in the way she incorporates slogans and headlines; Smith uses the disjointedness created by capitalisation as a way of evoking the ‘display’ of a newspaper headline and hence the collage of editorial and commercial voices that type unites under the smooth veneer of the singular author. This effect is possible precisely because of the impersonal, regular appearance of type.

Indeed, ‘Magnificent Words’, a poem published in her 1966 collection The Frog Prince, and Other Poems, Smith describes the bible verse that appears on the front of the Daily Telegraph as having been chosen for ‘display’.[50] C. T. Jacobi’s The Printers’ Vocabulary, explains that ‘display work’ refers to the presentation of ‘titles, headings, and jobbing work, [and] is thus termed to distinguish it from ordinary solid composition’.[51] Therefore, Smith’s use of ‘display’ is a quasi-metaphor whereby the implications of its usual use within the visual arts prompt the reader to arrive intuitively at the implications of its technical usage. Namely, that a piece of text is separated in such a way that demarcates it for close attention and fractures it from a whole to facilitate viewing from all angles. Smith’s capitalisation evokes an aesthetic of display that implies a degree of typographical authority over the organisation of a publication. At the same time, Laura Severin has highlighted that Smith’s isolation of phrases from their context generally has the opposite effect: ‘When narrative’s protective covering is carved away, isolated phrases stand out naked and vulnerable, their absurdity exposed.’[52] In other words, Smith heightens the reader’s visual perception of the status of these snippets so that the inanity of their content is made even more ridiculous. However, by withholding this capitalisation until the third item, she builds up to this aesthetic of ‘display’ by degrees and hence points to the subtlety of slippage between voices. In this way, magazines were enabled to disguise market incentives within the more familiar voices of columnists. The spectral presence of commercial interests makes them the ghost-writers of the popular press.

At the centre of both this passage, and Smith’s broader struggle to define the typescript in relation to the printed copy, is the way in which the impersonal appearance of type threatens to fracture its contents away from the author at every moment. Hence, she highlights a disjunction between the typescript and the printed copy by suggesting that their continuity with each other is only as strong as the visual continuity between any typographic text. Central to this idea is Smith’s use of the typewriter as a visual medium, and a persistent questioning of the material properties of her text at every stage of its creation. The idea that the idiosyncratic gesture of typing can produce not just a text that appears impersonal but that actively invokes external and potentially hostile texts is troubling. Like the ‘talking voice that runs on’, words, be they typed or spoken, cannot be retracted and take on an independent life of their own. The risk that they run away from their author or speaker’s intent is only intensified by the anonymising uniformity of print.

The extracts of external texts that Smith weaves through the novel are not limited to women’s magazines. Two passages that Pompey claims to have found in one of her notebooks present a fascinating engagement with the history of western philosophy and point specifically (if not explicitly) to the immediate concerns of the protagonist and her text. Pompey refuses to reveal the origin of the first extract, but it concerns nothing less than ‘the doctrine of the eternity of the universe’ and expresses ‘the view that every individual in it perishes, the type alone persisting and renewing itself in successive individuals’.[53] Following this, she quotes the nineteenth century novel, John Inglesant:

The cross of Christ is composed of many crosses, is the centre, the type, the essence of all crosses. We must suffer with Christ whether we believe in him or not. We must suffer for the sins of others as for our own; and in this suffering we find a healing and purifying power and element. That is what gives to Christianity in its simplest and most unlettered form, its force and life…[54]

When juxtaposed, the passages become reflections on the multiple meanings of ‘type’ and its ethical and philosophical ramifications. ‘Type’ literally refers to biblical typology whereby a person, place, figure or event in the Old Testament (the type) prefigures another in the New Testament (the antitype).[55] Biblically, ‘type’ provides a hybrid relationship between figures that are, on one level, equivalent to each other, whilst clearly remaining distinct and temporally separate entities. Pompey emphasises that the passages are ‘copied at such separate intervals’, perhaps pointing to a parallel between the relationship of type to antitype and the coexistence of temporal separation and corporal continuity in the body that does the copying (or, to use Barthes’s term, creates the gesture).[56]

Smith engages with this theological context, but embedding it in a text so concerned with the typographic simultaneously lifts ‘type’ and ‘unlettered’ into a new plane of signification. The inclusion of these extracts alongside Smith’s references to her own ‘typing’, suggests the biblical typology might offer a model for thinking about the typescript and the printed novels that succeed it as existing between the autographic (type and antitype as individual entities) and the allographic (antitype as a repetition of the type). In this way, it becomes a passage which considers whether a text ever is, at its core, ‘unlettered’. Is the novel a physical manifestation of the ‘talking voice’? Is the ‘word of God’ a voice or a written statement? And at the centre of this is the visual parallel between the cross of the crucifix and the rows of ‘x’, abstracted from their phonetic signification into one of shape (1935-1936, Fig.4). The ‘xxxxxxx’ that prevents us from reading indicates words sacrificed as soon as they have been written, and the fallible body of the author that makes the mistake.

This leads to the final definition of ‘type’ that Smith draws upon in her constant social commentary, that of taking a group of individuals and thinking of them in categories. We might speculate that Pompey’s antisemitism, and in particular her claim that ‘a clever goy is cleverer than a clever jew’,[57] is rooted in the need to project her own insecurities about her status as another type, the maligned ‘typewriter girl’[58] in conjunction with her lack of higher education, and difficulty finding a publisher for her poems.[59] There is an unpleasant irony, then, that the yellow of the paper that signifies the socio-economic limitations at the root of these insecurities would, three years later in 1939, become the colour of the stars that symbolised Nazi persecution of Jews across Europe.

Conclusion

The ability of art to affect human behaviour is one of the central concerns of Wilde’s Dorian Gray. When Dorian accuses his yellow book of having ‘poisoned him’, his corrupting mentor Henry dismisses his accusation, declaring that ‘Art has no influence upon action. It annihilates the desire to act. It is superbly sterile.’[60] This denial encapsulates the view that books are abstracted, entirely allographic works, a view that Novel on Yellow Paper seeks to disrupt. As both an object and a literary work, it asserts that books are material objects formed by the material circumstances of their creation. These circumstances range from the room in which a book is composed, the stationery available to its author, the commercially-driven demands of a publisher and, in many cases, the typists that are responsible for a text’s material creation. To say that this interaction with the material world ends at the point of publication, that these objects are received ephemerally without leaving any tangible trace on the reader, is a fiction that Smith demonstrates as increasingly ridiculous in a world saturated by advertising and in particular the consumerist-didacticism of writing targeted at women.

By consistently invoking the presence of the autographic typescript, Smith confronts the complacent incuriosity of readers as to the motivations of external interlocutors that corrupt texts in the process of their reproduction. Not only does this make readers vulnerable to textual manipulation, but it allows the whole array of a text’s ghost-writers to remain unseen and unacknowledged. Finally, as contemporary readers, continually confronted with the problems posed by adapting texts to our own sensibilities on the one hand and pursuing the purest authorial edition on the other, Novel on Yellow Paper also reminds us that there is value in being curious about the inherent, unavoidably adulterated, messiness of texts at every stage of their creation.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr Caroline Levitt for her guidance in developing the argument for this essay, Dr Helen Thaventhiran for introducing me to this text during my undergraduate degree and Rachel Alban for her patience during the editing process. I am very grateful to the Hull History Centre and University of Hull Archive Staff who (somewhat ironically) provided me with a digital copy of the original typescript.

Citations

[1] Stevie Smith, Novel on Yellow Paper (London: Virago Press, 1936), 15.

[2] Aubrey Beardsley and Henry Harland, eds, The Yellow Book: An Illustrated Quarterly, 13 vols (London: Elkin Mathews and John Lane / Ballantyne Press, 1894-1897).

[3] ‘The Yellow Book’, The British Library, (n.d.), https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/the-yellow-book). [02 March 2023]

[4] Oscar Wilde, ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’, n.p. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/174/174-h/174-h.htm. [18 January 2023]

[5] Beardsley and Harland.

[6] Smith (1936), 67; Michael Frayn, ‘From the Archive, 5 November 1960: Lady Chatterley’s Lover Cleared in Obscenity Trial’, The Guardian, 5 November 2014, sec. Books, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/nov/05/lady-chatterleys-lover-obscenity-trial-1960). [03 March 2023]

[7] ‘Prospectus to Volume 1’, in The Yellow Book (London: Elkin Mathews and John Lane, 1894), n.p. The Yellow Book Prospectus to Volume 1 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive. [10 January 2023]

[8] ‘Prospectus to Volume 1’, n.p.

[9] Stanley Weintraub, ed., ‘Introduction- The Yellow Book: A Reappraisal’, in The Yellow Book: Quintessence of the Nineties(New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1964), vii.

[10] Weintraub, vii.

[11] Wilde, n.p.

[12] Nelson Goodman, ‘Art and Authenticity’, in Languages of Art: An Approach to a Theory of Symbols (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1968), 99-126, 116.

[13] Goodman, 116.

[14] Bonnie Mak, How the Page Matters (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), 9.

[15] Romana Huk, Stevie Smith: Between the Lines (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York : Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 40.

[16] Harry A Maddox, What a Stationer & Printer Ought to Know About Paper (2) (London: J.Whitaker & Sons, LTD., 1919), 3.

[17] Roland Barthes, ‘Cy Twombly: Works on Paper’, in The Responsibility of Forms: Critical Essays on Music, Art and Representation, transl. Richard Howard (Berkeley and Los Angeles, USA: University of California Press, 1991), 157-176, 162.

[18] Barthes, 162.

[19] Stevie Smith, ‘What Poems are Made of’, in Me Again: Uncollected Writings of Stevie Smith (London: Virago, 1981), 127-129, 127.

[20] Barthes, 160.

[21] Barthes, 170.

[22] Smith (1936), 57.

[23] Smith (1936), 59.

[24] See ‘The Perfect Fake’ in Goodman, 99-102.

[25] Brassaï, Conversations with Picasso (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 93.

[26] Smith (1936), 28.

[27] Smith (1936), 60.

[28] Smith (1936), 119.

[29] Smith (1936), 12.

[30] Leah Price. ‘Introduction’, in Literary Secretaries/Secretarial Culture (Taylor and Francis, 2017.) n.p., [PDF] Literary Secretaries/Secretarial Culture by Leah Price eBook | Perlego. [20 January 2023]

[31] Smith (1936),17.

[32] Constance Hoster, ‘The Training of Educated Women for Secretarial and Commercial Work, and Their Permanent Employment’, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 65, no. 3353 (1917), 262–69, 265.

[33] Hoster, 265; Barthes, 160.

[34] Delphine Gardey, ‘The Standardization of a Technical Practice: Typing (1883-1930)’, History & Technology 15, no. 4 (April 1999), 313–42, https://doi.org/10.1080/07341519908581951. [15 January 2023]

[35] Smith (1936), 22.

[36] Victoria Olwell, ‘The Body Types: Corporeal Documents and Body Politics Circa 1900’ in, Literary Secretaries/Secretarial Culture, n.p., [PDF] Literary Secretaries/Secretarial Culture by Leah Price eBook | Perlego. [20 January 2023]

[37] Huk, 72.

[38] Huk, 72.

[39] Martyn Lyons, The Typewriter Century: A Cultural History of Writing Practices (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2021), 5, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ulondon/detail.action?docID=6475850. [30 January 2023]

[40] Smith (1936), 90.

[41] Hannah Sullivan, The Work of Revision (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013), 23.

[42] Sullivan (2013), 23.

[43] Hannah Sullivan, ‘Why Do Authors Produce Textual Variation on Purpose? Or, Why Publish a Text That Is Still Unfolding?’, Variants. The Journal of the European Society for Textual Scholarship, no. 12–13 (European Society for Textual Scholarship, 2016),77–103, 80, http://journals.openedition.org/variants/322. [20 March 2023]

[44] Sullivan (2016), 96.

[45] Smith (1936), 15.

[46] Hannah Sullivan, ‘Why Do Authors Produce Textual Variation on Purpose? Or, Why Publish a Text That Is Still Unfolding?’, Variants. The Journal of the European Society for Textual Scholarship, no. 12–13 (31 December 2016), 77–103.

[47] Smith (1936), 28.

[48] Smith (1936), 90.

[49] Jill Greenfield, and Chris Reid. ‘Women’s Magazines and the Commercial Orchestration of Femininity in the 1930s: Evidence from Woman’s Own’. Media History 4, no. 2 (1998), 161–174, 172, https://doi.org/10.1080/13688809809357942. [28 January 2023]

[50] Stevie Smith, The Frog Prince, and Other Poems, (London: Prentice Hall Press 1966), 90.

[51] Charles Thomas Jacobi, The Printers’ Vocabulary; a Collection of Some 2500 Technical Terms, Phrases, Abbreviations and Other Expressions Mostly Relating to Letterpress Printing, Many of Which Have Been in Use since the Time of Caxton (London : The Chiswick press, 1888), 32, http://archive.org/details/cu31924029491499. [15 January 2023]

[52] Laura Severin, ‘The Novels: 1936- 1949’, in Stevie Smith’s Resistant Antics (London: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997), 24–47, 32.

[53] Smith (1936), 103.

[54] Smith (1936), 104.

[55] Robert E. Reiter, ‘On Biblical Typology and the Interpretation of Literature’, College English, 30, no. 7 (1969), 562–71, 563, https://doi.org/10.2307/374005. [02 February 2023]

[56] Smith (1936), 105.

[57] Smith (1936), 13.

[58] Christopher Keep, ‘The Cultural Work of the Type-Writer Girl’, Victorian Studies 40, no. 3 (1997), 401–26.

[59] Frances Spalding, ‘Novel on Yellow Paper’, in Stevie Smith: A Critical Biography (London: Faber and Faber, 1988), 110-132, 111.

[60] Wilde, n.p.