The following in-profile article is the outcome of a conversation between Puerto Rican artist Gamaliel Rodríguez and Immediations Associate Editor, Ana Gabriela Rodríguez, which took place in San Juan, Puerto Rico on 20 July 2023.

First gaining attention for his monumental deep-blue ballpen ink drawings of abandoned yet futuristic-looking government and civilian structures in Puerto Rico, Gamaliel Rodríguez (b. 1977), known professionally as Gamaliel, is now one of the island’s most spotlighted contemporary artists. Having completed his MFA at the Kent Institute of Art and Design in 2005, Gamaliel took up drawing at the height of new media art and the internet boom, when more traditional art forms were being cast-off as conventional and dead-end alternatives. Pushing the technical possibilities of drawing on paper, a medium too often reduced to the preliminary sketch and preparatory process, Gamaliel experiments with ink, acrylic, ballpoint pen, and pencil to produce imaginative, almost photographic and print-like images. Deserted and deteriorating man-made structures such as military bases, religious buildings, airports and educational centres that once spatially and architecturally exerted varying constructs of power, transition into hybrid forms consumed by nature. He explains that his work considers the symbiotic and cyclical relationship between the economic and ecological, with nature ultimately reclaiming the power it had been stripped of by human material ambition.[1] Often travelling from his workshop in Cabo Rojo, on the west end of the island to the east in San Juan and coming across now abandoned and once important economic centres dating to as far as the island’s political annexation by the United States in the early twentieth century, Gamaliel pictures a world of failed development and collapse but also revival.

Taking part in the recent and landmark collective exhibition No existe un mundo poshuracán: Puerto Rican Art in the Wake of Hurricane Maria at the Whitney Museum of American Art, curated by Marcela Guerrero, Gamaliel’s featured artwork, in line with the show’s narrative, reflects on the fragile and precarious conditions that US citizens on the island have continually faced. These are conditions that, as suggested by the show, are not solely tied to the devastating natural effects of the category four hurricane but rather to centuries-long colonial histories.[2] Puerto Rico had been one of Spain’s oldest colonies before being ceded to the United States in 1898 and designated an official US Commonwealth in 1952. The title of The New York Times exhibition review, “Puerto Ricans Expand the Scope of ‘American Art’ at the Whitney”, suggests a broadened and more inclusive understanding of American identity.[3] However, as major museums begin to strive for wider considerations of nation-based identity and categories, artists such as Gamaliel, who would not have previously fit into canonical definitions of American Art, are in turn producing their own narratives from the inside-out and on their own terms. He notes that while working from the island and focused on Puerto Rico, he is aware that what is ‘going on here is happening in other parts of the world’, in other words, it transcends the Puerto Rican context.[4]Rather than thinking about how to adapt to the ‘centres’, Rodríguez’s artistic practice bends the power structures to make the ‘centres’ fit Puerto Rico.

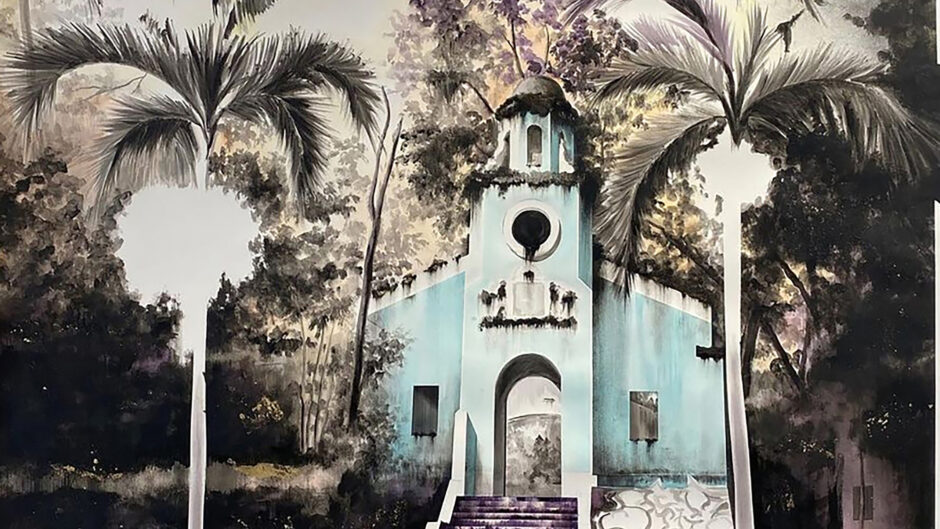

More recently experimenting with several colours in the same piece, in Correctional Faith (2022, Fig. 1), Gamaliel depicts a now forgotten 1930s church that was once part of a former or ‘antiguo’ early twentieth century correctional institution for minors in the coastal town of Cabo Rojo. Moss, vines, and natural elements have slowly altered the structure’s physical fabric. Through the arched doorway plants make themselves visible in the background in a once intimate space of religious worship. People, too, have left their mark, the graffiti serving as kind of societal acknowledgement of the building’s abandonment. However, the work gains further meaning when considering what has been purposefully left out of the image. The church’s relevance becomes evident when considering that its architect, Rafael Carmoega, also designed the island’s landmark ‘Capitolio’ or Capitol building in San Juan, seat of the Legislative Assembly. As Gamaliel explains, working from the periphery, away from the capital, helps to expose a different Puerto Rico to that of San Juan, the island’s ‘economic motor’.[5] According to the artist, Correctional Faith is about power in its multifaceted forms. Both built by the same renown state architect, the correctional church’s problematic yet religious function has been laid to waste for nature to take over while the capitol’s curated image remains a seemingly visible show of political and economic stability. Nonetheless, when looking at Puerto Rico or the world through its peripheral architectural remnants, the Capitol building or state power is reduced to illusion. Though there is ruin and wreckage in his abandoned structures, there is also the potential of a repurposed and sustainable space, where nature can coexist with the contemporary world.

Smoke too has been a recurring motif in Gamaliel’s artwork that calls to mind the symbiotic relationship and tension between the man-made and nature. As the artist argues, smoke is generally associated with negative events, chaos, and catastrophe and is the residue of a power exerted, whether it be through war, sabotage, or even natural disaster. However, as is also apparent in Correctional Faith and the cloud-like negative spaces surfacing from the palm trees, Gamaliel’s treatment of smoke might also just be fog, bushes, waves or other natural forms. Botanical life, plants and fruits, in turn serve not as exoticizing elements but as reminders of expansive and layered colonial histories and economic systems. The banana, a recurrent motif in his work, here symbolises the monopolisation and exploitation of Latin American and Caribbean lands by foreign corporations. Gamaliel is ultimately interested in the ambiguity of his images and the kind of multiple interpretations they can produce despite their overlooked historical and geographical specificities.

Often titling his works Figure while using a made up but seemingly important number, the artist frames his images as if they were meant to illustrate or reference a text. Purposefully drawn to resemble prints and photographic images pulled from archives, classified materials, and other official sources, Gamaliel questions the credibility and authenticity of today’s unregulated flow of information and news. Upon closer examination, his work goes beyond the human-nature symbiosis, as the materiality itself reveals further conceptual dimensions. During our conversation, the artist noted his surprise in realising that at times the most catastrophic and extreme outcomes result from the simplest acts. His use of the ballpoint pen as a medium reflects on this idea, as he points out that it is with the stroke of a pen that wars can be declared and the independence of a country claimed.[6] Moreover, his images dwell on the cyclical and ironically timeless nature of historical narratives, remarking that some of his oldest works have never been more relevant than today.

New York Times art critic Holland Cotter explains that one of the Whitney exhibition’s main arguments was to assert that ‘Puerto Rican realities, present and past, thrown into relief by Maria are also the realities of oppressed countries and cultures around the globe.’[7] Nonetheless, the conceptual possibilities of Gamaliel’s art call for a larger and more expanded world-view. Through his work we come to realise that the struggles of marginalised countries and cultures can no longer be seen as isolated but rather as part of an intertwined and arguably crumbling socio-economic global complex. As the world faces deepening and accelerated class disparities, alarming waste excess, and unprecedented climate change, these struggles have in many ways taken a global turn. Like Gamaliel, by looking at the world through the so-called margins rather than the seemingly thriving centres, we can unveil fresh perspectives and ways to deal with today’s interconnected challenges.

Citations

[1] Gamaliel Rodríguez in conversation with the author (20 July 2023). Unless otherwise noted, this conversation serves as reference for all other citations and information included in the article.

[2] For more on the exhibition, please refer to ‘No existe un mundo poshuracán: Puerto Rican Art in the Wake of Hurricane Maria,’ Whitney Museum of American Art, (n.d. accessed 1 August 2023, https://whitney.org/exhibitions/no-existe)

[3] Holland Cotter, “Puerto Ricans Expand the Scope of ‘American Art’ at the Whitney”, The New York Times, (25 November 2022, accessed 1 August 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/25/arts/design/puerto-rico-artists-maria-whitney-museum.html)

[4] Gamaliel Rodríguez (20 July 2023). Spanish citation: Lo que está pasando aquí, está pasando en otras partes del mundo.

[5] Gamaliel Rodríguez (20 July 2023). Spanish citation: el motor económico.

[6] For more on his use of ballpoint please refer to ‘Gamaliel Rodríguez: La Travesía/Le Voyage’, Mass MoCA, (n.d. accessed 1 August 2023, https://massmoca.org/event/gamaliel-rodriguez/).

[7] Cotter.