Ragnar Kjartansson is an Icelandic artist whose durational performance and video installations have been shown in two Venice Biennales and major solo exhibitions worldwide, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Barbican Centre, London; the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington D.C.; and the Palais de Tokyo, Paris. In December 2021, he premiered work and curated the opening exhibition for the launch of the V-A-C Foundation’s GES-2 House of Culture in Moscow. In conversation with Associate Editor Carla Kessler, Kjartansson discusses how performers and audiences experienced his recent works amidst the backdrop of war.

Let’s begin with your relationship to the theatre. You grew up around rehearsals for your parents’ plays, referring to Anton Chekhov as your babysitter. Your performance works embrace the theatre’s repetition and immediacy, while rejecting its demands on the audience to sit and stay from start to finish. Do you have any intentions around how people ought to experience your work, the way a director might create a story arc to bring the audience along a particular journey?

I remember my parents talking around the coffee table: ‘You know, we should really make them laugh in the third act, so they will actually cry in the fourth act!’ Theatre is a manipulative art form — of emotions. One of the reasons why I love visual art is its ambiguity — its emotional ambiguity. I sincerely believe that I can never make a piece that I actually understand myself. There has to be this kind of mystical element to it, as opposed to a theatre production where you really have to get the message. I’m always very careful not to blurt it out or give the audience an explanation of the world.

So you are chiefly concerned with not dictating how people make meaning of your work?

Absolutely. It’s almost like the electricity that makes an art piece; this mystery that you cannot really access, but you feel it. If I cannot get my head around what the piece means, then I want to do it, then I think it’s interesting.

Some of your works at the GES-2 in Moscow explore art under attack, either by enraged individuals or state censorship, which became way more than a conceptual theme when Russia invaded Ukraine. What can you tell me about that experience?

It was like the most interesting and complex experience of my artistic life. In 2017 I got the offer to open this building. Theresa Mavica, the director of the V-A-C Foundation, came to Iceland. She showed me the architectural plan and gave me Russian caviar, ‘a gift from the Russian people’, and said, ‘do you want to do this?’ As a sucker for Russian drama, you can imagine how intrigued I was. So much art I love is Russian and Ukrainian, and the war has reminded us of all the artists that we thought were Russian who are actually Ukrainian.

You curated this exhibition with Ingibjörg Sigurjónsdóttir and named it To Moscow! To Moscow! To Moscow! after Chekhov’s Three Sisters, which is also the title of a piece in the exhibition?

It’s a photograph, based on a story from my youth: an American friend of my parents’ named Jay Ranelli visited us in Iceland after he had been to Moscow, two years before the fall of the Soviet Union. McDonald’s had come to Moscow! It was Gorbachev’s glasnost, trying to open up. In my memory, this friend showed us a picture he took while he was waiting at the counter at McDonald’s, where three girls had the nametags Olga, Masha, and Irina. I remember him and my parents laughing so hard. They were like, ‘Oh, the three sisters, they made it to Moscow! Finally.’ For the show, I contacted his widow and sons, and they looked through all his archives for this photo. They couldn’t find it, so I restaged the photo in my studio in Reykjavík. In the GES-2, it was blown up and back-lit, like a light box in an airport, and hung high, like a billboard or a huge altar.

It feels like a counterpoint to your video series, Scenes from Western Culture (2015), looped vignettes in which children play tidily in the bucolic countryside, or a sharp couple dines in near silence.

It sort of is, but also a part of it. Putin’s propaganda is always about the west against Russian culture, that Russia is not western culture. It’s totally ridiculous. Russia is western culture; it would be like France denouncing western culture. It had its colonies and horrors it has not come to terms with. And then it also had many of the greatest western thinkers and artists that are a huge part of the canon. My friends in Pussy Riot like to emphasise that a cultural boycott of Russia plays into the hands of Vladimir Putin. The idea that Russia is a victim being culturally bullied by the west is the fuel of national propaganda. Boycott oil and gas, not Tchaikovsky.

How was it making this work in Russia five months ago?

It was a different world. One third of the cast and crew of Santa Barbara were Ukrainian. Moscow was still pretending to be normal, but something awful was looming. The atmosphere became more and more restrained every week from when we started working on the project in 2017.

The GES-2 was an experiment, like the last breath of liberal ideas in mainstream Russia. The building is in the centre next to the Kremlin, and when we came to install, all toilets were gender neutral. That’s a big pro-LGTBQ statement. Then, within two weeks before the opening, Putin had a two-hour press conference about the horrors of gender-neutral toilets. When we came to work the next morning, it was just panic, putting up ‘men’ and ‘women’ signs. But I saw how Russian resistance works, which is so poetic. It was like, ‘Ragnar, remember, you should always use the women’s toilet.’ So only the guys went to the women’s toilet and the women went to the men’s toilet, in quiet opposition.

If you take part in an art show in Russia, even if you are showing Matisse, you somehow have to deal with the oppressive regime. So we went ahead to create a show that was sort of a trojan horse, dealing with these things in a subversive way. And then I stumbled on this Santa Barbara theme.

This is the 1980s American soap opera that you recreated live, one episode a day, with Russian actors?

Yes. Alexandra Khazina in the education department at the V-A-C told me about an article in the American magazine Foreign Policy about the importance of Santa Barbara in Russian culture based on photographs by Misha Friedman. I read that article and then it was obvious what should be done. Misha has been a collaborator, the shadow cardinal, really, of this whole project. Years ago, he was in Lviv, Ukraine and saw a bus going to ‘Central Santa Barbara’. He took the bus and discovered how many post-Soviet neighbourhoods are named after Santa Barbara, and how important it was for ideas of capitalism to take form in Russia. I have it from the creators of Santa Barbara themselves, the Dobsons, that Soviet officials approached them for the rights to air it in the Soviet Union. The government saw the show as a good example of western TV, because it was an ironic take on American capitalism. But then, the Soviet Union collapsed and Santa Barbara came on TV a week after the fall and nobody understood it as irony — just a western blast of capitalism and hedonism turned up to eleven. The post-Soviet, Russian soul is made of Santa Barbara and Dostoevsky.

Santa Barbara is so important to Russian culture that it undermines the idea of nationalism.

Yes.

How many episodes did you make before you pulled out of the exhibition?

There were supposed to be 100, and we ended up with 81 episodes. My friend Ása Helga Hjörleifsdóttir directed them. We shot the last one on February 24th, the day the war started. In it, the main character was planning to kill her father. And she was dressed in yellow and blue, like the Ukrainian flag — this was just mystical coincidence. The costume and plot are directly from the 1984 American episode. But we cannot show pictures of that because the actor could get arrested.

Putin came to visit the GES-2. There is a picture of him posing in front of The End, Venice (2009), my paintings that are about the end of masculinity! I was really happy about that subversive context. When Putin visited, it was like a Potemkin Village for him. The performance was not on and most of the video works were put on pause. They made sure he saw very little of what was going on, because if he is pissed off, all is at risk.

The coolest, most insane thing that came out of this Russian show was that Pussy Riot started hanging out on the set of Santa Barbara. You can imagine what an honour for me that was. Misha Friedman introduced me to Masha Alyokhina, one thing led to another, and we now have a Pussy Riot division in our studio in Reykjavík.

I read that you helped one of them get out of Russia. What are you working on together?

Ingibjörg is part of an artist-run space called Kling&Bang here in Iceland, and we are planning to do an overview show of Pussy Riot in late November of all their actions with the Russian state. They’ve never done that. It was something we started to plot on the set of Santa Barbara.

Santa Barbara actually got the review that I am proudest of in my career. It’s in Meduza, an opposition media organisation that would naturally oppose GES-2, because it was paid for by an oligarch and blessed by Putin. It said that Santa Barbara was a veiled confrontation towards the Kremlin. You can imagine how happy I was with that. But now any subtleties are eliminated. You cannot do anything. Recently, a high-profile state museum in Moscow tried to put on exhibitions of old Russian art, but even they were stopped by the culture ministry. Putin’s regime rains terror and death on Ukraine and at the same time commits a cultural suicide for Russia. It is a reminder of how sloppy nationalists are. You’ve got this great culture and you just destroy it with stupid ideas of post-Soviet neo-Nazi ideas blessed by god.

Censorship is strongest in countries where art is deemed powerful.

Totally. One of my favourite things in this whole experience was, we decided to put a sign over the saucy stuff while shooting Santa Barbara, like when people were having a French kiss, so that children could watch. As a joke, I said, can you make a sign that says ‘censored’? Alarms went off in the institution, and they censored the sign saying ‘censorship’. When you are actually doing censorship, you cannot say ‘censorship’.

You make works that explore the idea of a nation, like Russia or American showbiz splendour; the cliché of a cultural form, such as the opera or rock music; or an archetype, like the male-artist-genius you mentioned in The End. What draws you to this idea or cliche of things that then gets deconstructed?

The artist Magnús Sigurðarson said that ‘the cliché is the ultimate expression.’ These words sank deep into me. Iceland became independent from the Danes in 1944, and the idea of creating a national identity was having an opera and putting on some Wagner. Then, you are a real nation! In the eighties when I was growing up, I remember this sense of wanting to be accepted as a western culture nation, not just this island of peasants up in the north. It meant adapting those big cultural clichés. Iceland developed a sort of an obsession with proving itself at all these things we now find so problematic.

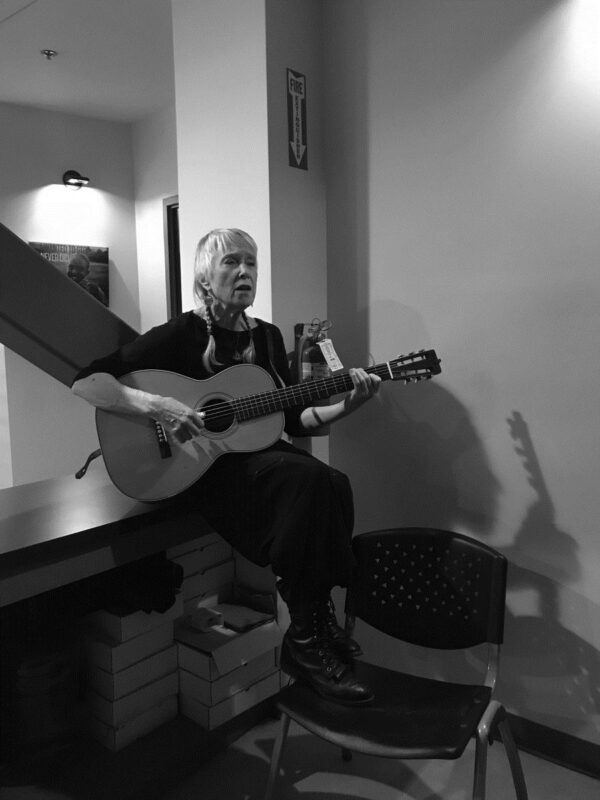

In many of your works, a super-cultural archetype gets extended and then stuck in a moment. The record starts skipping as the performer’s exhaustion shows, and it inevitably all breaks down the cliché. Woman in E (2016-2017) features a woman in a golden gown, who stands on a platform encased in tinsel, slowly playing the E minor chord on the electric guitar. In Romantic Songs of the Patriarchy (2018), women and nonbinary troubadours are staggered throughout the exhibition space, dressed in casual black, each singing a male-authored pop song on the acoustic guitar. Women with guitars also show up in the dance piece, No Tomorrow (2017). What does this recurring motif mean to you?

The guitar is a referential feast. It is often looked at as a weapon: the folk singer Woody Guthrie wrote ‘this machine kills fascists’, and in heavy metal music, the guitar is often referred to as an axe. Then there is all this imagery of rock with the guitar as a phallic victory symbol. Good gracious lord, think of Jimmy Hendrix and Prince.

Let’s talk more about how your performance works intervene in feminist and participatory art practice.

In art school, I took courses in feminist art and performance. It was a feast of new ideas, and really made me the artist I became. I was introduced to Marina Abramović and Carolee Schneeman, who luckily became friends and mentors years later. I always think of Carolee as the first to take the artist’s identity and body and make that the essence of the artwork. The nude stepped out of the patriarchal frame. As an aspiring feminist, I realized that patriarchy was embedded in me, and I became interested in my identity as the problem. Then I was surprised by working in America, where if you are a man, it’s considered ridiculous to say you are a feminist. It’s normal for guys to be feminists in Iceland, and I think that’s why we have had a lot of progress. The problem needs to cooperate.

I would maybe tweak that: when someone emphatically proclaims himself a feminist, there can be a suspicion that he thinks he’s a nice guy, but is covering for the fact that, deep down, he would actually like to preserve his patriarchal power, thank you very much!

The suspicion totally makes sense. But saying to myself and the world that I am a feminist helps me fight all the patriarchal thoughts and behaviour built up in my brain. Being a feminist does not necessarily mean you are a nice guy, but it hopefully means you are trying. The ego is tricky. It has been helpful to have a brilliant partner, and professional help, in investigating my own tendencies — like the ways I fool myself that I don’t need ongoing self-inquiry, as a proclaimed feminist! But I think it deters progress if we want people to be perfect.

Absolutely. The work of progress is to be imperfect, always. You’re never just done.

In 2009 I started to work with the idea of objectification in The End, Venice with male collaborators, but I started working on this subject with women in a piece called Song (2011), which I made with my nieces. It’s a video circling three blonde girls in a neoclassical space singing an Allen Ginsberg poem. This was sort of my gateway to making works with other performers, and not including myself.

Sometimes the problem I have with discourse on artists who use their own body as the medium is that it never goes beyond a conversation about the artist, their biography, and their identity. When an artist hires others to perform their vision, the conversation opens to so many other avenues. You do appear in some of those earlier works and in The Visitors (2012), but it’s not about you.

Absolutely. When I think it’s a good idea to use the idea of the artist in a piece, then I use myself.

With Song, it was a big responsibility for me as their uncle, just to be there with them at the Carnegie in Pittsburgh. Through the process we talked of their experience of life as young women and objectification. I hoped that they would learn the ridiculousness of it from actually doing the satire of it. My nieces were happy doing the piece. Now one of them is a visual artist, one a feminist rocker, and the third a poet. They were already on the way.

So, it started with that piece and continued with works like Woman in E. I have always been interested in feminist understandings of the world because I think the deep patriarchal violence in our culture is the root of all evil. We are racist, for example, because we are patriarchal. I am fascinated by this evil. In Romanticism, this evil is a classic lure, lovely on the surface.

We have talked about your paradoxical role as a white male artist putting women on a pedestal in Woman in E. In my research on the piece, I interviewed all twenty-seven performers and analysed audience reception on social media. What I found was that re-staging oppression or objecthood in an art context relocates its urgency. It invites consenting participants and spectators to enter an exchange that would be impossible or unsafe in real life, to explore difficult issues without real danger. Ultimately, Woman in E sustains a productive tension between exploitation and empowerment, or objecthood and subjecthood. How did that tension play out in Romantic Songs of the Patriarchy or No Tomorrow? Do you consider them sister pieces?

That’s what I was hoping Woman in E would do, and they are definitely sister pieces. The three sisters. No Tomorrow is a piece that has become a community of friendship, a band. Together with Margrét Bjarnadóttir, Bryce Dessner, and the performers, we have dealt with those themes while developing the piece for five years. It has been sheer joy.

The first iteration of Romantic Songs of the Patriarchy was also a joyous communal experience. Commissioned in 2018 by the C Project in San Francisco, the inspiration was a space in the Mission district called The Women’s Building. It’s basically a house where the patriarchy is being dealt with since 1979. It is a haven for women suffering domestic abuse; provides legal services to immigrant women in the area; and offers empowerment programs for girls, like mountain climbing.

Through the years I have put on the radio to listen to the patriarchy in our pop culture. When women performed these songs in San Francisco, they became a punch in the gut; they were turned around. A woman singing ‘She’s Always a Woman to Me’ by Billy Joel was really something interesting. I was there with Ingibjörg and our 8-month-old daughter, my studio manager Lilja Gunnarsdóttir, and composer Kjartan Sveinsson. The Women’s Building team was happy about it and the performers were content.

We did the performance again in 2021 at the Guggenheim, but I think the times had changed. Me Too and Black Lives Matter had turned up the urgency on all matters of our culture. Then because of COVID, I could only travel alone, and there was something off about a bearded man with suspenders coming to talk patriarchy and explain the work plan. One performer said, ‘I’m quitting this, I realise this is ridiculous. I am not going to help some guy deal with his issues.’ Actually, a good point. I think a lot of the performers got a shock, like, what did I sign up to do? It was a domino of discomfort. But also, a very understandable anger boiled over. Most of the performers signed up because they liked the contradictions in it, and a lot of them had actually done it before in San Francisco, but now something was off. This was the most uncomfortable performers have been with a performance I’ve done. It’s a hard-core piece with lots of emotional labour that just became overwhelming. It’s about what’s complicated; these songs are not written with malintent — that is written in a culture. And that is gut wrenching.

I heard a lot from the Woman in E performers that it was a useful exercise for them, but more difficult in practice than they imagined; durational performance brings out parts of you that might not come out in everyday life without that repetition to the point of exhaustion. People consent to doing something, but consent is ongoing. Does this make you think about how you might re-stage Woman in E?

I hope I have learned, and we will now be very careful to make people ready for the complexities.

Endurance is often accompanied by physical or mental difficulty, even if it’s temporary or agreed upon. Do you see the difficulty that comes with endurance as a necessary part of your practice?

Yeah. Weirdly, it’s almost the kick. I don’t want to plan short shifts. For myself and a lot of performers I work with, the hardship is the kick. On the surface it looks like it’s a sadistic thing, but I know that the experience will be much more interesting if you perform it for a long time. You’re going to get so much out of it, as a performer.

When we spoke two years ago, you said something that I’ve been thinking about since. You said that you see little difference between an audience person experiencing one of your works for six hours or two minutes. I’d like to revisit this. Why is endurance or difficulty a precondition for the performer, but not the audience?

Because the performer makes an enlightened decision about what they are going to do, but the visitor kind of stumbles upon it. I say this to emphasise that you don’t need to do it as an audience member, that the pieces are like paintings in a way.

What drives you to refer to Woman in E as a sculptural performance or Santa Barbara as a history painting?

I always think of works as sculptures or paintings. For me it is that simple. Performers in space are sculpture and video on screen is painting. I also think that you can enjoy it as a sculpture. With performance, then you have this presumption of form, of beginning, middle, end. I must watch it for the whole time?! But if it’s a sculpture, then I just can just glance at it.

I am trying to reckon with the fact that there’s a direct correlation between audiences who spend significant time with the work, and the intensity or depth of their experience.

I definitely agree with that, but I don’t want to say, ‘It’s really great to see this piece for a long time.’ If you are interested enough, you just do it yourself, and then it becomes your thing. Being raised in the theatre, this kind of manipulative art form, I want to give the viewer as much freedom as possible.

You want to give the viewer freedom, but the performer is a kind of tragic artist figure, lifting this weight.

Absolutely. It’s absolutely for the performer to lift the weight, and the performer knows that, and is willing to do it.

There is this Romantic notion that a significant experience or work of art requires struggle. Whereas the instantly knowable or felt is easy, it’s pop culture. It’s advertising. Your perspective on the performer is about holding something heavy. But your desire for the audience seems so much more inviting. I find it fascinating, your unwillingness to dictate what their experience ought to be, that they feel difficulty, directed or taught to in any way.

I try to avoid that at all costs. Ingibjörg and I talk about it a lot. She works in a very different medium as an artist; it’s sculptures about nothingness, awesome stuff. We cooperate a lot on the pieces. She taught me to never ever put one word in a wall text that says, ‘You will feel this in the piece.’ You really have to be careful with wall text.