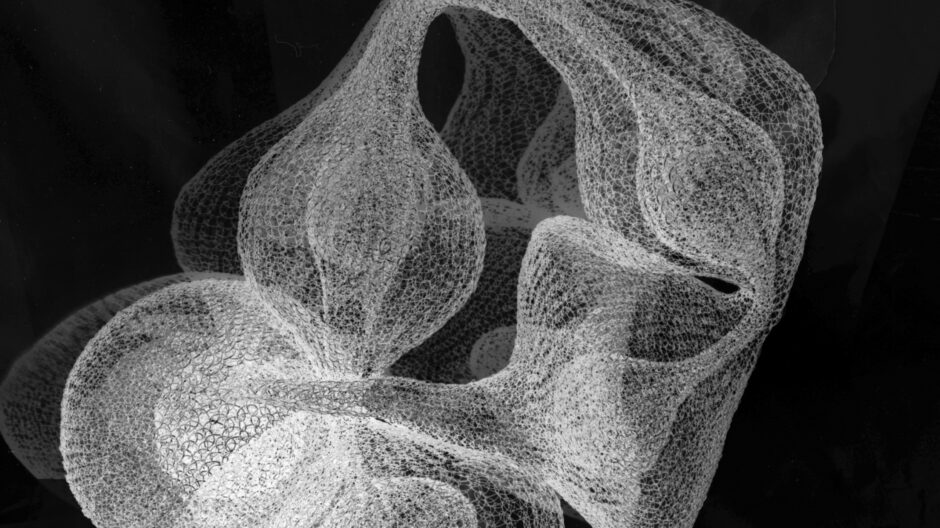

This article explores the themes of materiality and immateriality in Ruth Asawa’s looped wire sculptures. Encountering her hanging, multi-lobed sculptures at the exhibition Ruth Asawa: A Line Can Go Anywhere(David Zwirner Gallery, London, January – February 2020), the relationship between the material and immaterial becomes apparent. When viewed from a distance, the groupings of sculptures (2020, Fig. 1) appear intangible, ephemeral, like a corpus of interlocking silhouettes suspended in space. The effect of immateriality is enhanced by the sculptures’ transparency; the viewer can see through each work in a sequence of gossamer veils. However, closer inspection reveals that Asawa made each sculpture with thousands of small copper, brass or steel wire loops. She creates a series of forms within forms that simultaneously conjoin and dissolve into one another. The enclosed loops of wire nonetheless form tangible layers that disrupt their total transparency. Asawa’s sculptures embody tactile form while at the same time transcending it. I argue that central to Asawa’s looped wire sculptures is a conceptual and physical dialectic between their material presence and perceived immateriality.

Existing scholarship on Ruth Asawa (1926-2013) has separately addressed the role of materiality and immateriality in her process and the experiences of her sculptures.[1] Materiality and immateriality have been polarised in discourse on Asawa and have represented two distinct frameworks for analysing her practice. However, there has been limited examination of the relationship between these two concepts. This article contributes to scholarship on Asawa by examining the dialectical relationship between immateriality and materiality in her process and the experience of sculptures. In doing so, this article seeks to resituate Asawa’s practice within debates on American abstract sculpture of the 1960s and 1970s. As Asawa’s sculptures are porous and multi-layered, I argue that so too is her approach to materiality and immateriality. Asawa’s sculptures occupy a transitional space between the material and immaterial, the haptic and ephemeral, the embodied and transcendent, the present and the absent.

This article is structured into two sections. The first, ‘Materiality and Process’, centres around Asawa’s use of wire and air as her medium and her knitting technique. I explore how Asawa tested the formal, conceptual and material limits of her medium and process. The second section of the article ‘Immateriality and Space’ focuses on the experience of encountering Asawa’s completed sculptures. Here, I interrogate how the physical forms of Asawa’s sculptures lead to fleeting perceptual and spatial experiences. Through the two sections of this article, I seek to demonstrate that the relationship between materiality and immateriality is apparent at each stage of Asawa’s process and in the experience of her completed sculptures.

My analysis of materiality centres around Asawa’s use of wire thread and her process of ‘…knitting without needles …’.[2] I question how Asawa manipulated the qualities of wire to create the simultaneous effect of omnipresence and evanescence. Between 1946 and 1949, Asawa studied at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, working closely with Josef Albers. I examine how Albers’s dictums on materiality informed Asawa’s work. Aligned with recent debates on conceptualism in craft practice, I consider the implications of Asawa’s use of a technique rooted in craft to create modernist abstract sculptures.[3]

Meanwhile, my analysis of immateriality considers light, space, gravity and translucency. Buckminster Fuller’s principle of ‘ephemeralization’ is central to my analysis of immateriality, and I will use these terms interchangeably throughout the article. As scholars including Mary Emma Harris have noted, Fuller and Asawa developed a close relationship at Black Mountain College and had an extensive interchange of ideas.[4] In his collection of essays, Nine Chains to the Moon (1938), Fuller positions ephemeralization as the act of ‘…doing more with less …’.[5] Fuller initially applied this concept to scientific and industrial development rather than to visual art.[6] However, I argue that Fuller’s theory of ephemeralization has significant implications on understanding immateriality in Asawa’s work and American abstract sculptural practices of the 1960s and 1970s. Asawa’s sculptures stage the perceptual experience of moving from the ‘material to the abstract and … intangible’ yet are always bound to their material form.[7] Indeed, in Beyond Modern Sculpture, Jack Burnham powerfully observes this principle as a zeitgeist of sculpture in the 1960s; ‘as sculpture …., denies presence, reduces its mass’ it remains bound to a ‘theory of matter’.[8] My analysis on how material form leads to immaterial experiences in Asawa’s sculptures also contributes to recent debates by scholars, including Mari Carmen Ramírez, Martha Buskirk and Christian Berger, on the ‘material-identity’ of conceptual art.[9]

Asawa’s career spanned over five decades: from her earliest abstract sculptures, made as a student at Black Mountain in the mid-1940s, to her final public commission, The Garden of Remembrance, at San Francisco State University in 2002. Her oeuvre incorporates abstract work and an impactful practice as an arts educator and activist in her home state of California. Throughout her career, Asawa worked in various media, including drawing, print, bronze sculpture, and painting. However, from 1947 until the early 2000s, wire sculptures were her primary artistic focus. Asawa created a substantial body of looped and tied-wire sculptures, and this article exclusively addresses her looped-wire works.

Asawa’s oeuvre cannot be neatly divided into distinct periods. Rather, as Aiko Cuneo argues, her career can be characterised by a continuous engagement with different sculptural languages, many of which recur across her five decades of artistic activity.[10] In 1999, Asawa developed a specific terminology for each of her sculptural groups, which she called ‘typologies’.[11] Each typology refers to the specific formal characteristics of each group, such as ‘hyperbolic forms’ or ‘multi-lobed single layer forms’.[12] Consequently, I have chosen to follow Asawa’s sculptural typologies rather than to analyse her work from a specific period. This article centres around her ‘multi-layered interlocking forms and spheres’. I also examine Asawa’s ‘window form’ sculptures. I posit that Asawa invoked materiality and immateriality in the clearly defined structures of her ‘window form’ sculptures, which resulted in an architectural, or architectonic, spatial effect.

This article uses the conceptual framework of materiality and immateriality to interrogate the specific formal and experiential questions raised by Asawa’s sculptures. By situating Asawa’s work within debates on materiality and conceptualism, craft and art, absence and presence, this article raises questions pivotal to American abstract sculptural practices of the 1960s and 1970s.

Materiality and Process

Asawa’s approach to using wire plays with the modernist doctrine of ‘truth to materials’, popularised by sculptors including Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore during the 1930s. Her process celebrates wire’s inherent qualities of malleability, lightness and linearity. Simultaneously, Asawa’s technique was not bound to the limits of a block of wood or marble, characteristic of sculptures associated with ‘truth to materials’. Instead, Asawa may have been drawn to wire because of its transformative potential. Asawa’s mode of abstraction reflects Josef Albers’s dictum’s on materiality, which she encountered while taking his influential Basic Colour and Design Course at Black Mountain College in 1946. Central to Albers’s classes were his matière studies. Here, Albers taught students to use humble, everyday materials and transform them to create new visual and tactile experiences.[13] Robert Snyder has made the important observation that Asawa adopted a form of abstraction based on Albers’s approach to testing the limits of a material.[14] Central to Asawa’s process is the transformation of utilitarian material into a conduit for new spatial experiences. Her sculptures play with vision, oscillating between the perception of material form and the ephemerality of shadow.

Albers’s insistence on using everyday materials can be connected to a wider questioning of materiality in conceptual art practices of the 1960s and 1970s. Notably, in Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object (1966-1972), Lucy Lippard specified that artists used cheap, reproducible materials to achieve a sense of dematerialization.[15] Lippard’s writings on conceptual art have since dominated discourse on dematerialization. In Lippard’s theory of dematerialization, material form is merely a conduit for conceptual objectives: ‘… the idea is paramount and the material form is secondary …’.[16] However, I believe the dialectic of immateriality and materiality in Asawa’s work complicates the terms of Lippard’s debate. Everyday materials such as paper, grass or wire used by Asawa spoke to transience, ephemerality and impermanence rather than the fixture and grandeur of marble or bronze. Moreover, in her technique of looping strands of wire to create a layered effect, Asawa also implicated the passages of air as part of her medium. Asawa’s use of air as a sculptural medium invokes a dialogue with overtly conceptual contemporaneous works such as Robert Barry’s Inert Gas Series (1969) and Michael Asher’s Air Works (1970).[17] While Barry and Asher used air to create invisible, situational experiences, Asawa implicates passages of air alongside loops of wire to invoke a dialogue between materiality and immateriality. Positive and negative space and the absence and presence of material are inherent in Asawa’s approach to materiality.

Not only did Asawa work with a functional material, but her technique derived from a utilitarian craft. Asawa’s use of tightly interlocking wire loops originates in a traditional wire-knitting technique for making baskets to carry eggs from Toluca, Mexico. Asawa learned this technique from local craftswomen while working in Mexico as a volunteer art teacher for the American Friends Service Committee in the summer of 1947. On returning to Black Mountain College, Asawa initially began making functional baskets out of wire, notably giving one as a Christmas present to Anni Albers in 1947.[18] Asawa’s construction technique for her early baskets mirrored the process and form she had learned in Mexico. The Mexican baskets and, concomitantly, Asawa’s sculptures had an underlying conceptual message relating to their technique, form and function. Created from cheap and readily accessible materials, these baskets served a specific material usage and were designed to be ephemeral.

By 1948, Asawa had developed the wire-knitting technique to make closed enmeshed forms. In doing so, her formal language shifted from basketry and object-making to sculpture. Shifting the function of her technique from object-making to sculpture, Asawa’s process can be understood through Fuller’s theorisation that: ‘the more abstract the means of accomplishment the more specific the results.’[19] Her sculptures are ‘abstracted’ from the traditional function of the wire-knitting process. However, Asawa simultaneously uses the wire-knitting to invoke the formal and conceptual ephemerality of the original basketry process. Her process can be understood through Jenni Sorkin’s theorisation of a fleeting and ethereal ‘…threshold space ….’ which is revealed between abstract sculpture and object-making.[20]

Echoing Julia Bryan-Wilson’s arguments on Harmony Hammond’s Floorpieces (1973-1984), I contend that there are political implications to Asawa’s use of textile-craft.[21] Both Asawa and Hammond reclaimed techniques traditionally associated with working-class, domestic production: Asawa’s process originates in a Mexican basketry technique and Hammond’s in a technique for creating rag-rugs. Bryan-Wilson argues that Hammond’s use of the weaving technique and spiral pattern structure overtly invokes a lesbian-feminist semiotic.[22] By contrast, I believe that there is a subtle politic to Asawa’s process and mode of abstraction. As a Japanese-American, Asawa experienced racism throughout her life. Notably, following the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, Asawa and her family were interned at the Santa Anita racetrack in California in 1942. Aruna D’Souza has made the powerful observation that Asawa’s technique creates subliminal racial metaphors.[23] Asawa’s process of looping wire into mesh-like layers creates sculptures that play with visibility and invisibility, absence and presence. As such, the dialectical relationship between materiality and immateriality in her process can be understood as a metaphor for Asawa’s own experience of her racialised identity as a Japanese-American living in the United States during the Second World War.[24]

Untitled (S.077) (1978, Fig. 2) evokes the way in which Asawa’s sculptures complicate definitions of craft and art. The sculpture comprises seven enmeshed oval lobes stacked on top of one another. Five oval lobes have spheres nestled inside them, signalling how the delicate eggs were protected in the original basketry process. The stacked form could also be an allusion to the cumulative nature of collecting eggs. However, the sculpture is also a purely abstract form and can be experienced without knowing the original function of the basketry process. As Helen Molesworth observes, the enmeshed spheres and ovals in this sculpture are subtly asymmetrical and imbalanced, subverting the modernist trope of repetition and difference.[25] Additionally, Untitled’s stacked columnar composition could allude to the work of the early modernist sculptor Constantin Brâncuși. Brâncuși frequently stacked repeated stone or wood units to create column-like structures, most famously in Endless Column (1937). In both Asawa’s and Brâncuși’s work, the effect of stacking invokes both a material presence and transcendental elevation into space.

Untitled (S.077), demonstrates the innovative way that Asawa used craft processes as a means of artistic experimentation. Nonetheless, the origins of Asawa’s technique and her gendered and racialised artistic identity were used by critics to denigrate her work as lacking innovation, contributing to Asawa’s marginalisation within art histories.[26] For example, in a 1955 review of Asawa’s work, Otis Gage stated, ‘the technique has its disadvantages … that relates these objects uncomfortably to baskets and fish traps …’.[27] Asawa’s sculptures, however, do not deny their genetic relationship to function but astutely invoke concurrent dialogue about materiality, conceptualism, the boundaries of craft and art, and the politics of process.

Asawa also engages with the capacity of wire to reflect light. As Jack Burnham theorises, light became a ‘…medium of expression …’ and a means of transcending material form in sculpture of the 1960s.[28] However, discussion of light in relation to sculpture of the 1960s has focused on commercial and industrial light sources such as Dan Flavin’s use of fluorescent tubes.[29] Burnham asserts the use of commercial and industrial light sources in sculpture raises conceptual questions of ‘…what light is at our stage of technology …’.[30] Meanwhile, Asawa’s invocation of light through the natural properties of wire is more meditative. There is no ‘on’ or ‘off’ switch or literal light source connecting her work to a specific technological moment. Rather, the capacity of wire to reflect light imbues the surface of Asawa’s sculptures with an organically ethereal appearance. This effect is most notable in works such as Untitled (S.693) (1956, Fig. 3), where Asawa uses iridescent brass and iron wire. Comparisons can be drawn with Marisa Merz’s use of copper wire in sculptures such Untitled (1975). Sorkin has argued that both Asawa and Merz accentuate the inherent luminosity of copper, brass and iron through their process of shaping wire into small concentric circles using knitting and weaving techniques.[31] Contorted into wavering patterns, Asawa and Merz’s materials reverberate light and create a multi-dimensional and diaphanous surface that belies the density of wire loops.[32]

While Asawa’s sculptures have been poetically described as invoking a sense of ‘fragile wonder’, they are physically strong: the material properties of wire counteract her medium’s perceived ephemerality.[33] It is notable that Asawa developed her wire works from her drawings. Her early drawings and wire sculptures are connected through the flexibility inherent in both media: wire becomes a three-dimensional investigation of a two-dimensional line. Indeed, Asawa stated ‘a line can go anywhere’ evoking the compositional flexibility of a drawn line on a sheet of paper and the flexibility of a coil of wire to infinitely unravel.[34] Asawa fully exploited the flexibility of wire, shaping it into fine loops that give her sculptures a porous appearance. The loops of wire join and contract while simultaneously retaining their physical form. Tamara Schenkenberg has observed that wire has a high tensile strength that, once curved, will not break as the material holds a fixed shape.[35] The combination of flexibility and strength in the wire drove Asawa to ever more complex curved structures that expanded to a monumental scale. Her largest multi-lobed sculptures extend to twenty-one feet in length from top to bottom.

Wire is physically insubstantial, and Asawa utilised this material property to create a sense of weightlessness in her sculptures. Untitled (S.077) (Fig. 2), unlike many of Asawa’s larger sculptures, is made from a continuous strand of copper wire, which she looped to create a lightweight and meticulously balanced structure of nesting lobes.[36] Though Untitled (S.077) demonstrates Asawa’s technical ability to work with continuous wire, in the majority of her sculptures, she prioritised the perception of weightlessness by combining different wire gauges to form the appearance of a continuous surface.[37] In her complex, multi-lobed sculptures, she often created the smaller, interior forms using the narrowest gauge of wire, and she used progressively thicker gauges to form the outer layers. Asawa’s structure concealed the breaks and joins between her different strands of wire. The effect of using multiple wire strands to create a unified surface gives her sculptures the structure and appearance of total continuity: Asawa’s sculptures float weightlessly. Her sense of insubstantiality is enforced by her use of loops incorporating space into the form of the sculpture itself. Asawa’s sculptures appear – in Fuller’s words – to be ‘…ephemeralizing-towards-pure-energy …’ through their continuous looped passages of wire and air.[38]

Resultingly, Asawa’s sculptures evoke spatial volume instead of material mass. Emily Doman Jennings insightfully interprets the importance of volume over mass in Asawa’s sculptures by applying the ideas of the painter and theorist László Moholy-Nagy.[39] In The New Vision (1938), Moholy-Nagy identifies a fourth stage of sculptural development. Here sculpture moves from an emphasis on material mass to spatial and volumetric relationships through a breadth of formal strategies, including the creation of porous structures. Moholy-Nagy theorises that there is a symbiotic relationship between the ‘…lightening up or dissolution of material … and creation of ‘….weightless volume relations …’. [40] Moholy-Nagy’s theory resonates with Asawa’s approach to materiality. Using looped wire strands to form porous structures which create volume instead of mass, Asawa’s sculptures invoke conceptual questions of form and weight in sculpture.[41]

Imogen Cunningham’s photographs of Asawa’s sculptures, captured between the 1950s and 1970, further dramatize the relationship between volume and mass. Both based in Northern California, Asawa and Cunningham shared a strong friendship that manifested in their intimate understanding of each other’s work.[42] Cunningham frequently photographed Asawa working on and posing with her sculptures, often alongside Asawa’s six children at their home in San Francisco. In addition, Cunningham captured Asawa’s sculptures as isolated aesthetic objects detached from their material origins.

The relationship between volume and mass is most notable in Cunningham’s colour-negative photographs of Asawa’s sculptures, such as Form within a Form Sculpture on The Floor 2 (1951, Fig. 4). Here, Cunningham emphasises volume as a sculptural element by highlighting the different geometric forms and negative spaces in Asawa’s sculpture. Asawa’s sculpture appears to be defined by white light, creating a sense of total weightlessness. Within Cunningham’s photograph, the inner spheres of the sculpture emanate the brightest light, which radiates through the outer layers of wire. Moreover, Cunningham’s photograph creates a sense of wire layers emanating out from and dissolving into one another, as if animating the process of ephemeralization through evanescent lines of light. Through Cunningham’s lens, Asawa’s sculpture appears in motion. Multiple fleeting forms move in and out of focus as our eyes notice different elements of the colour-negative. Geraldine Johnson has argued that photography has played a central role in ‘…documenting and defining …’ sculptural ephemerality.[43] Johnson applied her argument to the temporally ephemeral sculptural performances of Asawa’s contemporary Eva Hesse.[44] However, Johnson’s argument also resonates with Cunningham’s photographic reimagining of Asawa’s sculptures. By accentuating the appearance of ephemerality in Asawa’s sculptures, Cunningham obscured their structural strength.

Asawa’s process of using individual strands of wire to create sculptures that conceal their structural strength can also be seen as reflecting Fuller’s principle of ephemeralization. Fuller identifies a central characteristic of ephemeralization as doing ‘more and more with less until eventually, you can do everything with nothing.’[45] A theme in Asawa’s oeuvre is the growth and evolution of forms, which Jason Vartikar has recently interpreted as reflecting a system of cell division or mitosis.[46] Within each of her sculptural typologies, Asawa explored how to do ‘more and more’. For example, she increased the number of lobes, the complexity of forms, or the intricacy of structure. Nonetheless, Asawa’s technique remained the same: the sculptures are entirely created from looped strands of wire. In Asawa’s process, increasing the number of loops of wires increases the effect of ephemerality while inversely strengthening the sculpture’s form. Therefore, Fuller’s concept of ephemeralization can be applied to Asawa’s repetitive process. The effect of increasing the number of loops simultaneously makes each less important. Asawa’s sculptures stage an interesting paradox: the more materially present they are, the more the sculptures evoke a sense of immateriality. This principle can more broadly be applied to the effect of Asawa’s use of wire as her dominant medium. By making her material omnipresent, it simultaneously becomes invisible.

Asawa also used repetition to invoke a sense of the infinite. In The Infinite Line, Briony Fer identifies the relationship between structures of repetition and the experience of infinity as a theme in art after modernism.[47] Like the tight, rhythmic patterns of Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Net paintings such as No. F (1959), the tiny loops that compose Asawa’s sculptures, such as Untitled (S.334) (1953-1955 Fig. 5), appear to go on forever. Their three-dimensionality and transparency further emphasise the effect of infinity. Asawa’s sculptures invoke a sense of temporality through their repetitive forms. Her use of rhythmic loops of wire prompt consideration of the intensely time-consuming nature of making the sculptures. In an oral history interview with Harriet Nathan, Asawa stated it was unsurprising that she was drawn to repetitive and durational tasks as the basis of her art-making.[48] Asawa had grown up on a farm and from a young age learned recurring, monotonous processes in the growing and harvesting of vegetables. Through their dense structure of repeated wire loops, Asawa’s sculptures lead the viewer to consider the continuity of time and the infinity of space. Asawa’s sculptures invoke the immateriality of space through the materiality of form.

![Hanging Fifteen-Lobed [Seven Open and Eight Interlocking] Continuous Form), ca 1953-1955, enamelled copper wire](https://courtauld.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Fig-5-1-211x700.jpg)

Immateriality and Space

In his essay ‘Ruth Asawa: Line by Line’, Jonathan Laib asserts that Asawa was less interested in the material aspects of wire than she was in exploring space.[49] Countering Laib’s position, I argue Asawa’s exploration of space emerges symbiotically with her exploration of wire. As Gerald Nordland aptly identified in a review of Asawa’s first solo show in Los Angeles in 1962, Asawa manipulated wire to create a ‘…heightened sense of space …’.[50] This both results from and transcends the materiality of wire.

The principal means through which Asawa achieved a ‘heightened sense of space’ was by making her sculptures transparent.[51] Asawa contorted the wire to produce thousands of small openings making the sculptures solid forms that were also fluid and transparent. The simultaneous effect of solidity and transparency in Asawa’s sculptures is enhanced by their layered structure. Solid material and void space become structural equivalents of one another, invoking an architectonic sense of space.

Transparency was also a central characteristic of modernist architecture.[52] In buildings such as Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye (1928-1931), the glass ribbon windows and open colonnade create the illusion of structure that is freely floating, as solid and void materials dissolve into one another. This effect is comparable to the ephemeralization of Asawa’s sculptures through material transparency. It is notable that Fuller was an architect and Asawa witnessed his architectural projects while at Black Mountain College. In his design for the Dymaxion House (1927), Fuller invoked transparency through his principles of ephemeralization. In both the Dymaxion House and Asawa’s sculptures, such as Untitled (S.114) (1958), transparency is created through a system of openings within a lightweight curving, metallic structure. Consonant with Fuller’s theory of ephemeralization, in Asawa’s Untitled (S.114) and Fuller’s Dymaxion House, a system of openings are used to create a dynamic energised structure. As a result of their transparency, Fuller’s Dymaxion House and Asawa’s Untitled simultaneously become intangible while showing the viewer their material complexity.

The effects of transparency in Asawa’s sculptures are most apparent when they are hung in groups. Indeed, grouping was Asawa’s preferred method for her sculptures to be displayed both in exhibitions and at her home, where she would suspend vast assemblies of sculptures from her ceiling.[53] Assembling the sculptures into groups also alters our understanding of their form and medium. Asawa’s sculptures shift from individual units to larger cohesive installations. The boundaries between each object blur due to their material transparency, creating a capacious and architectonic spatial effect. Through exploring the limits of sculpture and installation, Asawa’s work speaks to the interrogation of material and medium specificity, characteristic of American abstract sculpture of the 1960s and 1970s. Alex Potts theorises that the challenge to formalist doctrines of medium specificity was a movement away from sculpture’s tactile form and material and toward the ‘liquidated’ and ‘hybrid spectacle’ of installation.[54] When hung in groups, Asawa’s works become hybrid structures between sculpture and installation. Asawa uses the tactile properties of wire – its flexibility and weightlessness – to invoke the phenomenological spectacle of installation.

In her essay ‘Lessons in Transparency’, Ann Reynolds argues that when hung in groups, Asawa’s sculptures evoke both ‘literal’ and ‘phenomenological’ transparency.[55] The sculptures are ‘literally’ transparent due to their material qualities.[56] Meanwhile they are ‘phenomenologically’ transparent in that the groupings create ambiguous spatial and perceptual experiences heightening viewers’ awareness of their bodies in space.[57] In contrast to Reynolds’s argument that ‘literal’ and ‘phenomenological’ transparency are two distinct modes of perceiving Asawa’s sculptures, I argue that the concepts are interconnected. ‘Phenomenological’ transparency is not only created by grouping Asawa’s sculptures but from the shifting states of the material, or ‘literal’, transparency in each sculpture.

The interconnectivity of ‘literal’ and ‘phenomenological’ transparency is powerfully evoked in an installation of Asawa’s sculptures in the David Zwirner Gallery exhibition, Ruth Asawa: A Line Can Go Anywhere (2020, Fig. 6). Here, the viewer looks through the sculptures onto a sequence of seemingly never-ending layers of wire mesh. The material transparency, fluidity of line, and repetition in each sculptural form make the sculptures appear to merge and multiply, evoking Fuller’s principle of energy expanding through ephemeralization, thus creating the sensation of immateriality.[58] In the David Zwirner Gallery installation, Asawa’s sculptures are suspended from the ceiling, hanging at various heights, and positioned adjacent to and in front of one another. As a result, the viewer can look up, around and through the sculptural grouping. The materiality of the sculptures both encapsulates space and opens up the space surrounding them. Meanwhile, the individual wire loops are simultaneously omnipresent and invisible. As the viewer’s eyes adjust to each sculpture’s materiality, we stop noticing it, perceiving the group of sculptures as sequences and patterns reverberating through space. In groupings such as this one, the materiality of wire creates experiences of spatial immateriality.

Asawa uses transparency to create perceptual illusions. Asawa stated that by using looped wire, the spectator ‘… can see right through my sculpture, so no matter what you see, you can always see through it.’[59] Asawa’s statement captures her awareness of the optical conceit in her sculptures. The ‘multi-lobed-interlocking forms’ are created from a process of interlinking continuous wire loops that create the effect of shapes freely suspended inside one another.[60] Asawa’s enigmatic statement – ‘no matter what you see’ – invites viewers to doubt if the forms they have seen inside the sculpture are tangible or phantom.[61] Her ‘multi-lobed-interlocking forms’ both incorporate interior forms while simultaneously evoking impermanent spectral shadow objects. In this way, Asawa’s sculptures can be connected to a questioning of vision and perception within conceptual art practices of the 1960s and 1970s.[62]

Molesworth has described Asawa’s sculptures as a ‘meditation on emptiness’.[63] However, I believe Asawa’s sculptures not only ‘meditate’ on emptiness. Rather they create a new artistic proposition on the relationship between emptiness and fullness, absence and presence, volume and mass. For Asawa, meditating on emptiness meant defining space through the line and creating volume instead of mass. Untitled (S.563) (1956, Fig. 7) exemplifies Asawa’s use of the volume of emptiness. Untitled (S.563) at once appears full and empty, to be imbued with mass and yet to be weightless. Asawa manipulated wire to create curving forms that invoke the sensation of contracting and expanding – inhaling and exhaling – as air passes through the porous, curving layers. The sculpture is composed of a six lobed form, where double-layers in five of the lobes interlock as they travel from inside to outside and inside again creating a rhythmic vertical column. Each layer is demarcated through a wire line that contours the different spatial planes. Untitled (S.563) is in constant flux between fullness and emptiness as we see passages of space adjacent to tubes and spheres of wire. Asawa concealed spheres within three lobes, complicating the sensation of emptiness, most notably in the central section, which encloses two darker spheres. Nonetheless, it is still possible to see through the sculpture by focussing on the gaps between each layer. John Yau has argued that Asawa’s sculptures ‘….oscillate between solidity and dematerialization …’.[64] However, Untitled (S.563) does not appear to ‘oscillate’ between emptiness and fullness or solidity and immaterially, so much as it occupies a liminal space between these states. Additionally, Yau’s use of the word ‘dematerialization’ can be interpreted as signalling to Lippard’s use of the term, which foregrounds the concept over the material.[65] Untitled (S.563) demonstrates how Asawa manipulates the properties of wire to create complex spatial experiences of immateriality.

In sculptures including Untitled (S.563), Asawa also utilises the qualities of wire to confound expectations of gravity and the movement of mass in space. Suspended from the ceiling instead of rising from a base, her sculptures appear to float, further challenging formalist doctrines of medium specificity. Moreover, Asawa’s sculptures can be interpreted through Jack Burnham’s theorisation of contemporaneous ‘air-borne sculpture’. Burnham argues that the liberation of sculpture from its base invokes a new proposition on mass and energy.[66] Sculpture is no longer bound to formalist concerns but rather represents a ‘migration of physical form toward another area of activity’.[67] Asawa’s sculptures simulate the effect of transcending their material presence. In her sculptures, material form acts as a conduit for invoking an immaterial and spatial ‘area of activity’.

The effect of defying gravity is operative within the structure of each of Asawa’s ‘multi-layered interlocking forms and spheres’. In Untitled (S.563) (Fig. 7), we expect the sphere in the upper lobe to fall. It does not appear to touch any part of the sculpture, and the density of wire loops gives it the appearance of weight. Instead, the sphere remains suspended, floating as if buoyed by air and confounding expectations of gravity. The wire’s material lightness and Asawa’s looping techniques enable the optical deceit of Untitled (S.563). The seemingly infinite pattern of small repeated wire loops prevents the viewer from detecting how Asawa conceals the forms inside one another. Other sculptures by Asawa simultaneously deny and lead the viewer to reflect on gravity. In Untitled (1960-1963), we see five internal spheres spaced at intervals on a vertical axis. Although each sphere slightly differs in shape and scale, the serial nature of the forms suggests that the spheres are moving through the sculpture. Evoking Fuller’s theorisation of ‘… ephemeralizing-toward-pure-energy …’, the sculpture’s curved wire layers create a sense of continuous, dynamic rhythm.[68] As a result of their lighter tonality and vaporous structure, the curved outer layers resemble currents of energy flowing through the sculpture, transitioning from material form to evanescent experience.

I believe it was not only their formal similarity that led Asawa to name a group of her sculptures ‘window forms’, but a broader ambition to create an architectonic sculptural space. The window forms are amongst Asawa’s most ethereal sculptures, characterised by the looseness of their wire loops and composition of large openings surmounted by delicate crests of wire.[69] In 1954, Asawa developed her window form sculptures after she mistakenly cut her wire, causing the metal to split and twist into an ‘open window shape’.[70] The release of tension in the wire’s mass created a more open and less tightly defined form. In the window forms, the material weight of wire resulted in increased sculptural immateriality. For example, Untitled (S.039) (1959-1960 Fig. 8) is an elongated oval form dominated by vertical arcades of ‘windows’. Looking through each ‘window’ offers a view onto another or into the interior of the sculpture. While the openings resemble windows, the sprays of wire surmounting them resemble billowing canopies on a multi-storey building. Moreover, the structure of repeated openings makes the sculpture appear to infinitely rise like a high-rise building. It is notable that the first publication to feature Asawa’s work was Domus (1952), an architectural magazine, demonstrating the appeal of her work to those concerned with creating spatial structures. However, the lightness of Asawa’s material contradicts the architectural analogy. Structurally, the sculpture has an architectonic quality yet the sprays of wire and openings also echo the form of feathers which make the sculpture appear to float.

Asawa’s approach to architectonic space in both her ‘window forms’ and ‘multi-layered interlocking forms and spheres’ can be compared to Fuller’s Geodesic Domes, such as the Montréal Biosphère (1967), which Fuller developed through his principle of ephemeralization. It is notable that Asawa had witnessed Fuller’s experiment into domed architecture during his Summer Building Programme at Black Mountain College in 1948.[71] The Montréal Biosphère, made from steel and acrylic, has an expansive and volumetric sense of space as a result of its spherical form and materials. Both Fuller and Asawa created spaces of sculptural and architectonic immateriality, which directly arose from their materiality.

In this article, I have argued that materiality and immateriality are at the core of Asawa’s practice. These concepts are not binary opposites. Rather, like each loop in Asawa’s knitting process, materiality and immateriality are conceptually and physically bound together. Through the two parts of this article, I have demonstrated that the intersection of materiality and immateriality is apparent at each stage of Asawa’s process and in the experience of her sculptures. Asawa’s sculptures are in equipoise between these two states: between the material fixedness of wire and capacity to transcend it. Fuller’s principle of ephemeralization has been central to my analysis. I have argued that Asawa manipulates the properties of wire to open space, dissolve form and create temporal objects. This article has engaged in debates of materiality in conceptual art, medium specificity, dematerialisation and ephemerality, craft and art and the relationship of sculpture and installation. Asawa’s work is increasingly attracting scholarly interest and gaining visibility in museums. However, she has remained side-lined in narratives of American abstract sculptural practice of the 1960s and 1970s. By exploring materiality and immateriality in Asawa’s work, this article seeks to contribute to a wider recontextualization of her practice within art histories.

Citations

- See for example, Zoë Ryan, ‘There is Design in Everything: The Shared Vision of Clara Porset, Lola Álvarez Bravo, Anni Albers, Ruth Asawa, Cynthia Sargent and Sheila Hicks’, in Zoë Ryan (ed.), In A Cloud, In A Wall, In A Chair: Six Modernists in Mexico at Mid-Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019) 20-65; Jonathan Laib, ‘Ruth Asawa: Line by Line’, in Jonathan Laib and Robert Storr (eds), Ruth Asawa: Line by Line [exhib.cat.] (New York: Christie’s, 2015), 8-18.

- Marilyn Chase, Everything She Touched: The Life of Ruth Asawa (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2020), 50.

- Glenn Adamson, Thinking Through Craft, (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2007), 58-65.

- Mary Emma Harris, ‘Black Mountain College’, in Daniell Cornell (ed.), The Sculpture of Ruth Asawa: Contours in the Air [exhib.cat.] (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 42-67.

- R. Buckminster Fuller, Nine Chains to the Moon (Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 1938), 276.

- Fuller, 279.

- Fuller, 276.

- Jack Burnham, Beyond Modern Sculpture: The Effects of Science and Technology on the Sculpture of This Century (New York: George Braziller, 1968), 111.

- Mari Carmen Ramírez, ‘Tactics for Thriving on Adversity: Conceptualism in Latin America, 1960-1980’, in Philomena Mariani (ed.), Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s-1980s [exhib.cat] (New York: Queens Museum of Art, 1999), 53-73; Martha Buskirk, The Contingent Object of Contemporary Art (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003); Christian Berger, Conceptualism and Materiality: Matters of Art and Politics (Boston: Brill, 2019).

- Tamara H. Schenkenberg et al., ‘Evolution of Form’, in Tamara H. Schenkenberg (ed.), Ruth Asawa: Life’s Work [exhib.cat.] (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 130-146.

- Schenkenberg et al., 130.

- Schenkenberg et al., 130-134.

- Chase, 44.

- Ruth Asawa: Of Forms and Growth, Video Recording, Directed by Robert Snyder, (Santa Barbara: A Masters & Masterworks Production, 1978), [accessed 1 July 2021].

- Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object 1966-1972 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), vii.

- Lippard, vii.

- See for example, Kavoir Moon ‘From Air to Architecture: Michael Asher’s Early Air Works’, in Berger (ed.), 57-89.

- Tiffany Bell, ‘Ruth Asawa: Working from Nothing’, in Anne Wehr (ed.), Ruth Asawa [exhib.cat] (New York: David Zwirner Publications, 2017), 11-30.

- Fuller, 279.

- Jenni Sorkin, ‘Five Propositions on Abstract Sculpture’, in Paul Schimmel and Jenni Sorkin (eds), Revolution in the Making: Abstract Sculpture by Women 1947-2006 [exhib.cat] (Los Angeles: Hauser and Wirth Publishers), 140-157.

- Julia Bryan-Wilson, ‘Queerly Made: Harmony Hammond’s Floorpieces’, The Journal of Modern Craft, 2.1 (March 2009), 59-80, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2752/174967809X416279 doi: 10.2752/174967809X416279. [1 July 2021]

- Hammond, 65-67.

- Aruna D’Souza, ‘Transparency and its Other’, in Schenkenberg (ed.), 45-52.

- D’Souza, 46.

- Helen Molesworth, ‘“San Francisco Housewife and Mother”’, in Schenkenberg (ed.), 35-45.

- Sarah Archer, ‘Maker to Market: Ruth Asawa Reappraised’, The Journal of American Craft, 8.2 (July 2015), 141-154,https://doi.org/10.1080/17496772.2015.1054707, doi: 10.1080/17496772.2015.1054707. [1 July 2021]

- Otis Gage, ‘Sculpturama’, Arts and Architecture (February 1955) 4, 8-10, 30.

- Burnham, 286.

- Burnham, 303.

- Burnham, 303-304.

- Sorkin, 151.

- Sorkin, 151.

- ‘Fragile Wonder’, American Craft (June/July 2015, accessed 1 July 2021, https://www.craftcouncil.org/magazine/article/fragile-wonder).

- Ruth Asawa and Stephen Dobbs, ‘Community and Commitment: An Interview with Ruth Asawa’, Art Education (Reston), 34. 5 (September 1981), 14-17, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3192471, doi:10.2307/3192471. [1 July 2021]

- Schenkenberg, 11-35.

- Addie Lanier correspondence with the author (20 July 2021).

- Lanier (20 July 2021).

- Fuller, 279.

- Emily K. Doman Jennings, ‘Critiquing the Critique, Ruth Asawa’s Early Reception’, in Cornell (ed.), 128-138.

- Doman Jennings, 47-48.

- Doman Jennings, 47.

- Chase, 88.

- Geraldine Johnson, Sculpture and Photography: Envisioning the Third Dimension (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 1.

- Johnson, 1.

- Fuller, 279.

- Jason Vartikar, ‘Ruth Asawa’s Early Wire Sculpture and a Biology of Equality’, America Art, 34.1 (Spring 2020), 2-19, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/709413, doi: 10.1086/709413. [1 July 2021]

- Briony Fer, The Infinite Line: Remaking Art After Modernism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 1-5.

- Ruth Asawa and Harriet Nathan, The Arts and Community Oral History Project, Ruth Asawa: Art, Competence and Citywide Cooperation for San Francisco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), 35.

- Laib, 10.

- Gerald Nordland, ‘Los Angeles: Ruth Asawa’, Artforum International, 1,1, (June 1952), 8, https://www.artforum.com/print/reviews/196206/ruth-asawa-78071. [1 July 2021]

- Nordland, 8.

- Ann Reynolds, ‘Lessons in Transparency: Ruth Asawa in Mexico’, in Ryan (ed.), In A Cloud, In A Wall, In A Chair: Six Modernists in Mexico at Mid-Century, 173-179.

- Cornell, 138-165.

- Alex Potts, ‘Tactility: The Interrogation of Medium in Art of the 1960s’, Art History, 27.2 (April 2004), 282-304, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.0141-6790.2004.02702004.x, doi: 10.1111/j.0141-6790.2004.02702004.x. [1 July 2021]

- Reynolds, 174-175.

- Reynolds, 174.

- Reynolds, 175.

- Fuller, 279.

- Katie Simon, ‘A Conversation with Ruth Asawa, Artist’, Artweek, 26, 8 (8 August 1995), 17-18.

- Schenkenberg et al., 133.

- Simon, 18.

- Berger, 3-15.

- Molesworth, 39.

- John Yau, ‘Ruth Asawa, A Pioneer of Necessity’, Hyperallergic (September 2017, accessed 1 July 2021, https://hyperallergic.com/401777/ruth-asawa-david-zwirner-2017/)

- Lippard, vii.

- Burnham, 47.

- Burnham, 47.

- Fuller, 279.

- Schenkenberg et al., 138.

- Schenkenberg, 23.

- Harris, 47.