TRANSMISSIONS.TV

Season 1: six weekly episodes, 23 April-29 May 2020

Season 2: eight weekly episodes, 9 September-30 October 2020

Season 3: six monthly episodes, March-June and September-October 2021

Overlapping voices swell as bemused faces peer into monitors and fade to a glitch:

Hi, hello.

I see you!

Do you know this guy?

Have they started yet?

I don’t see anybody!

Hellooo?

This scene was broadcast into millions of living rooms in 1969, fifty years before videoconferencing technology would spark analogous re-enactments in home offices across the globe. Allan Kaprow made ‘Hello’ for WGBH-TV’s The Medium is the Medium, the Boston public television programme that also introduced a wide public to the major video artist Nam June Paik.[1] In April 2020, London-based artist Tai Shani and curators Anne Duffau and Hana Noorali launched TRANSMISSIONS, a digital platform that has since commissioned and screened twenty hour-long episodes of new media work. Born of but not defined by Covid-era constraints, it is a most compelling new entry in the history of art for the small screen.

TRANSMISSIONS shares a feminist politic with Shani’s work, which is both lyrical and uncompromising in its trans-inclusivity and opposition to capitalism and racism. Says the artist, solidarity requires ‘building a house you may never live in yourself’, as opposed to equal rule in one ‘that is rotten to its very core’.[2]Audiences can stream live episodes at no cost on Transmissions.tv, with two showings to accommodate varying work-life patterns and time zones. Artists are all offered compensation to participate in a solo or group presentation. Season three, for example, opened in March 2021 with the classic feminist performance Martha Rosler Reads ‘Vogue’ (1982) along with new works by Wu Tsang and Peter Spanjer that both explore the extremities of living in a gendered and racialised body. At a time when commercial and charitable institutions clamour for social-justice credibility and attention with now-more-than-ever urgency, TRANSMISISONS is refreshingly accountable to its artists without fanfare and with a sense of creative and cultural pluralism.

Consider two episode-length commissions that foreground the political and spiritual registers of the programme: a video essay by Paris-based artist Christelle Oyiri that explores self-fashioning in popular culture, and a participatory meditation exercise by the Ignota Books collective in London. Shown in April 2021, Not a gimmick, a punchline deftly samples clips from social and traditional media sources. Oyiri’s cut features a memorable compilation of sparring matches from the reality television show Love & Hip Hop on VH1. In it, a white presenter-type affects rationality as he lights fireworks amongst the cast of predominantly Black women. With little affection and virtuosic flow, they critique one another’s bodies, sartorial choices, and sexual pursuits. There were ‘pubic hairs flying’, says one participant to communicate the intensity of a particular altercation. Oyiri offsets the verbal warfare with visually spare clips of Black girls joyfully filming each other around an apartment block under a grey sky.

In Kaprow’s ‘Hello’, acquaintances greet one another in a staged performance that brings absurdity and consciousness to an otherwise unconsidered act. This principle, which the artist outlines in Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, is central to reality television. Its producers hire people to play themselves in a postmodern world that understands the self to be inherently unfixed and unstable.[3] Meanwhile, editors mine around-the-clock footage for one explosive moment, a skillset Oyiri observes is well suited to military intelligence. Reality TV would seem to follow a more manipulative playbook than Allan Kaprow’s.

One recent study of Love and Hip Hop confirms that it is edited to favour the performance of negative stereotypes.[4] In interviews with young Black American women who watch the programme, they approach it with enjoyment and humour alongside some concern for how the tropes will be interpreted outside their community, described as an under-resourced high school in a major metropolitan setting.[5] Oyiri is among the reality show’s viewers and commentators who enact Stuart Hall’s concept of reading mass media oppositionally.[6] The artist offers a counter-archive of guilty pleasure that preserves pleasure and exchanges guilt for criticality.

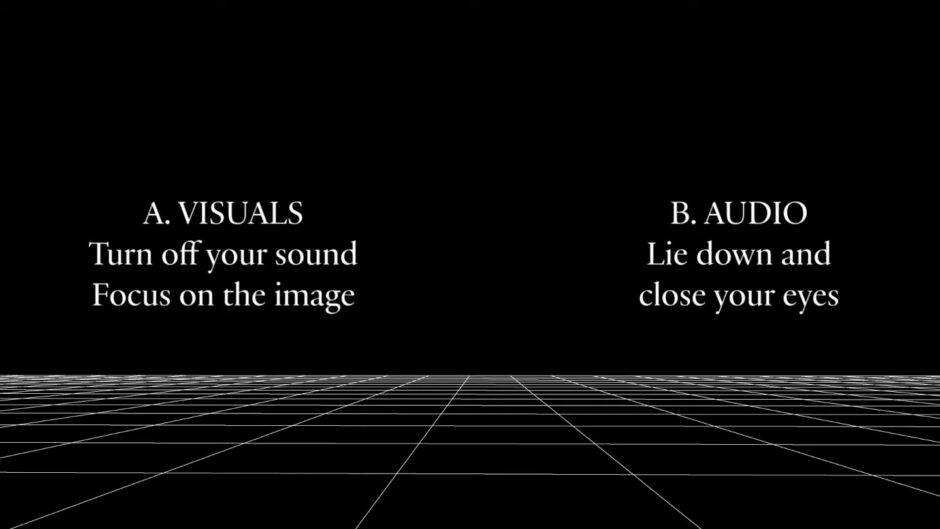

In Deep Deep Dream, debuted by Ignota Books in October 2020, the letters ‘A’ and ‘B’ appear in white serif typeface on a black screen, hovering over a plane of thin white orthogonal lines that disappear menacingly into the horizon.[7] Spectators are prompted to choose path A, which leads to a visual, somatic, and sonic experience in that order, or path B, which is structured in the reverse. The direct address recalls a gentler version of Paik’s voiceover in Electronic Opera Number One on The Medium is the Medium, 1969: ‘This is participation TV; please follow instruction.’

Rust-coloured, mitochondrial forms undulate on screen like psychedelic bile under a microscope. Tree of Knowledge, No. 1 (1913) by Swedish modernist Hilma af Klint glides across the monitor as a soft voice urges listeners to ‘know nothing, feel everything’ and then leads a Kundalini yoga sequence. The hallucinatory visual landscape and meditative drone of Deep Deep Dream share more than a name with Google’s DeepDream software, which generates Artificial Intelligence (AI) art, as well as composer Pauline Oliveros’s Deep Listening practice.

As the piece concludes, the phrase ‘CULTURE IS NOT YOUR FRIEND’ flashes on screen in block text like a storm warning. The same intertitle is printed on a rather stylish tote bag for sale on the Ignota website, along with thoughtful publications on occult ritual for the digital age. Was this a sincere exercise in awakening consciousness, a critique of how millennial paganism participates in the neoliberal economy, or both? Though I longed for dialogue, Deep Deep Dream is served well by the release of self-consciousness that solitude can provide. There is value to be found in surrender to a mysterious experience, to dull the protective impulse and slow the rush to always and immediately make sense of things.

Where liveness demands attention, the live stream derives communicative potential by inviting guidance and choice in how to inhabit an experience. Rather than attempt to replicate the live art encounter on a laptop, which would only emphasise the physical distance and lack of contingency, TRANSMISSIONS takes digital proximity as its point of departure.

Citations

- Allan Kaprow, ‘Hello’, The Medium is the Medium, WGBH-TV, 1969, 16:57 min, colour, sound; https://www.eai.org/titles/the-medium-is-the-medium.

- Tai Shani, ‘Feminism’s Occult Imagination’, artist talk organised by Edwin Coomasaru and Rachel Warriner, The Courtauld Institute of Art Research Forum (London, 19 October 2020).

- Sven Lütticken, ‘Performance Art After TV’, New Left Review 80 (March/April 2013), 116-117, 128-129.

- Erica B Edwards, ‘“It’s Irrelevant to Me!” Young Black Women Talk Back to VHI’s Love and Hip Hop New York’, Journal of Black Studies 47.3 (2016), 273-292, 283; see also Bettina L Love, ‘A Ratchet Lens: Black Queer Youth, Agency, Hip Hop, and the Black Ratchet Imagination’, Educational Researcher 46.9 (2017), 539-547; Melvin L Williams, ‘My Job To Be a Bad Bitch: Locating Women of Color in Postfeminist Media Culture on Love and Hip-Hop: Atlanta’, Race, Gender & Class 23.3-4 (2016), 68-88.

- Edwards, 289.

- Edwards, 290.

- Ignota Books, Deep Deep Dream (aired 14-16 October 2020, accessed 17 July 2021, https://ignota.org/blogs/news/deep-deep-dream).