The article addresses the interior decoration of an eighteenth-century French commercial space: the printmaker Gilles Demarteau’s Parisian shop La Cloche, painted by the academicians François Boucher, Jean-Honoré Fragonard and Jean-Baptiste Huet. Reconstructing and analysing both the shop’s pictorial scheme and architectural space, this essay argues that commercial spaces were important sites of identity formation. Gilles Demarteau’s shop played an active role in negotiating a new activity – shopping for prints – that was both commercial and cultural in nature. In particular, the shop shaped novel artistic practices, which were formative in the development of a new social type in Parisian circles: the amateur. The shop constitutes an exceptional example of the growing semi-public spaces dedicated to art in the second half of the eighteenth century.

On 23 March 1761, the weekly gazette L’Avant-coureur advertised four new prints by the printmaker Gilles Demarteau (1722-1776).[1] According to the advertisement, The Education of Love (1761, Fig. 1), a print after a drawing by François Boucher depicting Venus and Cupid was remarkable for the ‘purity of the drawing’, the ‘softness of the crayon marks’ and the ‘shine of the colours’ and was for sale for 30 sols at La Cloche, rue de la Pelleterie in Paris. Emphasising the newly invented crayon-like etching, which faithfully imitated the chalk of the draughtsman’s stroke, the advertisement’s tangible description was sure to pique the art lover’s curiosity and to generate the desire to admire the print firsthand at Demarteau’s shop.[2]

Shops and retail spaces had undergone considerable transformations as the luxury market expanded in Paris, sustained by the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763 and the liberal politics lead by the Foreign Minister the Duc de Choiseul.[3] Parisian shops had acquired the status of tourist sites and established themselves as fashionable urban places publicised in travel guides. In addition to public buildings such as the Louvre, the Séjour de Paris (1717) encouraged readers to stop at the Palais for shopping.[4] Along with artists’ workshops, domestic interiors and outdoor fairs, luxury shops, such as those held by marchands-merciers, emerged as alternative semi-public cultural spaces that shaped polite sociability and artistic taste.[5] Demarteau’s shop La Cloche of which only fourteen decorative paintings have survived, forms an exceptional visual testimony of such hybrid spaces and of their elaborate interior meant to attract a fashionable clientele.

Painted between 1765 and 1770 by François Boucher, after whom half of Demarteau’s prints were created, and by Jean-Baptiste Huet, the second most reproduced artist of Demarteau’s workshop, the decorative paintings (ca 1765-1770, Fig. 2) share close thematic connections with the prints commercialised in the room.[6] The context in which Demarteau commissioned the painted salon remains unknown. However, Demarteau engraved two portraits of Huet, one depicting him at work and the other exhibiting his profile in a medal to his glory, which offer a valuable testimony of their close professional and personal ties.[7] Demarteau even bequeathed one of his snuffboxes to his dear friend and painter Huet. Similarly, Demarteau’s gold box decorated with an enameled portrait of Boucher stood as a token of his attachment to this artist and friend.[8]That Demarteau bequeathed this enamelled portrait to his friend Blondel d’Azincourt from whom he borrowed most of the reference drawings of Boucher further confirms the strategic function of the object in strengthening personal ties between the artist, the merchant and the collector.[9]

The panels, each framed by a green trellis and carved wood paneling at the bottom, are made up of four doors and their over-doors, four larger perspectival landscapes by Huet populated by peaceful birds, sheep, rabbits and dogs and two narrow panels depicting a pair of nesting doves and a resting sheep and dog. Putti statues set in gardens adorn the doors with emblematic designs by Boucher and Jean-HonoréFragonard. The four over-doors painted by Huet and depicting the union of two doves confirm his reputation as a talented animal painter.

By promising that Demarteau’s prints were sure to ‘equally appeal to young artists and amateurs’, the Avant-coureur advertisement identifies which audience and hosts Demarteau potentially had in mind when he commissioned this fresh interior.[10] At the time, the amateur emerged as a new social type in Parisian artistic circles. According to Charlotte Guichard, this specific figure of the Enlightenment typically collected and commissioned art, attended academic institutions, socialised with artists, and engaged in scholarly writing and non-professional artistic practice.[11] While Demarteau had originally specialised in printed drawing books for artists as technical aids, they soon gained considerable traction in amateur circles, who increasingly drew for leisure.[12] The crayon manner, which had been invented by the printmaker Jean-Charles François in 1757, and perfected by Demarteau in the following years, allowed him to produce exact copies of drawings faithfully replicating the colours, lines and friable texture of chalk. These fac-similé prints appealed to amateurs eager to possess cheap copies of the original drawings they could not afford.[13] Prints, as the art dealer François-Charles Joullain put it, satisfied the collecting ambition of amateurs of all classes.[14] Even the wife of a Parisian paver for instance, could amass a substantial collection of prints.[15] In the context of emerging populuxe goods, defined as inexpensive copies of aristocratic luxury objects, fortune was not so much a prerequisite as the ability to exercise taste. [16]

While recent scholarship has shed light on the development of the amateur figure, it has predominantly focused on public and domestic spaces, such as salons, galleries, and ateliers.[17] Commercial spaces have received comparatively less attention in respect of their role in the formation of amateur identity. Shops have been examined primarily from the perspective of producers due to the types of sources available such as inventories and accounts books.[18] How they contributed to the emergence of a public sphere of art has received less attention. This article explores this blind spot by contextualising the amateur figure in a site-specific commercial space and by approaching La Cloche from the perspective of consumers. In line with the belief that commercial spaces were important sites of identity formation, this article argues that Demarteau’s shop played an active role in negotiating a new activity – shopping for prints – that was both commercial and cultural in nature. If, according to Charlotte Guichard, amateur identity was not achieved by mere ownership of prints, but through their appropriation and possession, Gilles Demarteau’s elegant boutique, I show, facilitated such processes.[19] Purchasing prints at La Cloche allowed clients to perform amateur identity and integrate a taste community.

One significant challenge to understanding retail spaces in eighteenth-century France is that, in contrast to the prolific writings on the aristocratic hôtel and country house by architects such as Jacques-François Blondel, the theoretical foundation for commercial architecture was almost inexistant.[20] Another specific difficulty or barrier? resides in the scarcity of primary sources, as the inventory taken of Demarteau’s effects at his shop on 6 September 1776 after his death was marked missing in 2006 by the Minutier central des notaires de Paris.[21] This article therefore relies on excerpts from the inventory transcribed in Jacques Wilheim and Henri Bouchot’s writings, as well as a manuscript transcriptions of the original inventory of Demarteau’s will at the Musée Carnavalet.[22] However, the lack of precise description of Demarteau’s interior, the absence of floorplans and of elements documenting the commission of the scheme hinder our ability to identify a definitive order for the arrangement of the canvases.

The ensemble’s complex provenance also calls for caution. After Demarteau’s death in 1776, his nephew Gilles-Antoine purchased and installed the panels in his apartment at the Saint-Benoit cloister. They remained there until 1890, when their owner Monsieur Dubos sold them leading to their dispersion.[23] They were reunited by M. Groult who installed them in his hôtel on the avenue de Malakoff before they were moved to rue du Bac.[24] The replacement of the original canvases and multiple conservation undertakings have modified the format of the original compositions.[25]

To overcome these limitations, I rely on recent scholarship on the anthropology of architectural spaces and furniture and the history of the senses. This literature examines the agency of the moving body in the construction of social spaces and considers decoration, furniture and objects as active agents structuring sociability. By attending to the bodily interaction of customers within the commercial interior, encompassing the visual, tactile, auditive and olfactive aspects of shopping for prints, it is possible to develop a more complete understanding of the agency of the painted panels. This article adopts the consumer’s perspective and a structure that speculatively follows an amateur’s consumer journey. From the expectations created by advertising to the shopping experience itself, it aims to reconstruct the physical, social, and imaginary spaces of La Cloche and to establish their role in the formation of amateur identity. More broadly, the article demonstrates the contribution of architectural space, decorative painting, and furniture to the process of internal subject formation and to the emergence of a new social type in artistic circles.[26]

ALLURING ADVERTISEMENTS

Advertisements for artists and printmakers in particular considerably increased in the eighteenth century and one’s first encounter with Demarteau’s shop may first have taken place on paper, through such alluring announcements in gazettes.[27] For instance, in May 1767, the Avant coureur praised three heads etched by Demarteau after Boucher for their technical achievement in reproducing the drawn lines of the eminent artist.[28] A few months earlier, the Mercure de France had offered an eloquent description of a print by Demarteau after Charles-Nicolas Cochin and invited readers to acquire it at La Cloche, rue de la Pelleterie’.[29] In 1769, Demarteau’s shop was also listed in Roze de Chantoiseau’s Almanach, which inventoried and facilitated the location of the most reputable workshops in Paris.[30] The intensification of advertisements for Demarteau’s work between 1767 and 1769 coincides with the decoration of his shop interior and shows evidence that the commission was part of a broader marketing strategy at a turn in the printmaker’s career. In 1767, Demarteau presented his first two-colour plates to the Académie de Peinture et de Sculpture, before he was admitted as a member in 1769. He likely looked to capitalise on his new status to attract a new clientele. Indeed, the textual nature of these advertisements addressed a more well-read audience than the strolling pedestrians purchasing from street sellers, where Demarteau’s prints used to be sold occasionally.[31]

Potential customers also learned about the shop from the prints themselves, exhibited in the social circles they frequented. The margins of Demarteau’s prints such as the Venus and Love for instance, incorporated strategic information in the cursive inscriptions below the frame: ‘Sold in Paris, at Demarteau’s, rue de la Pelleterie, at à La Cloche’[32]. Above the shop address, co-exist the eminent names of the artist Boucher after whom the print was etched, of the wealthy collector Monsieur De La Haye, to whom the print was dedicated, and of the prestigious amateur Monsieur Blondel d’Azincourt, from whom the original drawing was borrowed. Katie Scott demonstrated the critical role that inscriptions in print margins played for constructing artistic identities.[33] It can be argued that they also functioned as strategic devices for shaping the social and imaginary spaces of shops: by placing prominent names above and around the inscription La Cloche, Demarteau convened, at least visually, the illustrious amateurs in his boutique. The prints created desirability by advertising La Cloche as an elite social site, where refined amateurs were expected to be found. To visit the shop, thus, represented a chance to identify with the prestigious names on paper, and the promise of finding a place in an elite community. Moreover, the eminent names meant to be examined in the margins encouraged the amateur practice of establishing provenance and attribution and thus engaged viewers’ connoisseurial skills. The prints thereby gave potential clients a foretaste of the artistic experience awaiting them in the shop.

As marketing devices meant to create desirability, the inscribed names were not, however, a straightforward reflection of the shop’s habitual clientele. Name-dropping advertised La Cloche as a fashionable establishment. The imaginary space conjured up by the inscriptions operated as a nodal point, tying artists, amateurs, collectors, and prospective clients together, in the fiction of a shared social network and connoisseurly practice.[34] The dedication of each print to an individual of a different social status such as the painter Alexis Peyrotte or the state general of finance Monsieur Bergeret facilitated the identification by a wide array of potential buyers: artists, financiers and high nobility. For instance, that both the goldsmith and printmaker Jean-Denis Lempereur and the Marquis de Marigny, Madame de Pompadour’s brother, owned Demarteau engravings attests of the socially diverse clientele Demarteau developed.[35]

GETTING THERE

According to the writer Germain Brice in Nouvelle description de la ville de Paris (1725), printmaking workshops typically concentrated along the rue Saint-Jacques, on the left bank.[36] La Cloche however, was located at the heart of the luxury trade and metalwork neighborhood, along the old crossroads of Paris on the Ile de la Cité, an island which accommodated 800 shopkeepers.[37] The unconventional location of Demarteau’s print shop on the rue de la Pelleterie, typically housing silk and wool dyers, who used the access to the Seine to rinse textiles, can perhaps be accounted for when considering his background.[38] Unlike most Parisian printmakers who worked in their father’s workshop, Gilles Demarteau, born at Liège in 1722, was the son of a master gunsmith and trained as an engraver of metal objects.[39] To secure a working and living space in Paris, he rented La Cloche from a master dyer specialised in hats.[40]

Judging from the luxurious furniture and belongings that are listed in Demarteau’s wealthy interior, the location of the shop apparently did not hinder his affluent business.[41] Natacha Coquery has demonstrated that elite consumers valued quality of craft over shop location and thus were willing to travel long distances to purchase from the best artisans and merchants across Paris.[42] While aristocratic dwellings concentrated in the Faubourg Saint-Honoré and Saint-Germain, and the western areas of the city, this fashionable elite willingly crossed the Seine to pay Demarteau a visit. To find their way through the maze of narrow, circumvoluted city lanes, Parisian shoppers memorised shop signs. These precursors of house numbering did not necessarily reflect the trade of their owners.[43] Hence, long before Demarteau moved there in 1745, the shop sign La Cloche, meaning ‘The bell’, was indifferently used to indicate the workshops of a dyer, a merchant, a carpenter and a goldsmith.[44] Readers made aware of his shop through prints and advertisements would have recognised Demarteau’s boutique.[45]

Many shopkeepers invested important expenditures in decorating their shop’s outward façade to attract clients. Monsieur Dubosc for instance, a silk merchant in the rue Saint-Denis, called upon Guibert, sculptor for the Bâtiments du roi, to design his boutique doorway.[46] However, instead of an open storefront, La Clochewas more likely accessed through the door of a narrow building, after climbing one or two flights of stairs, thus heightening the sense of a more intimate visit.[47] Indeed, the painted room was described in the artist’s inventory as the entrance room serving as magasin d’estampes, a term denoting a retail or storage space, removed from the street, as opposed to the boutique.[48] While guild regulations compelled most craftsmen to work from a workshop open onto the street for public transparency, the unique status of printmakers, unregulated by the guild system, permitted a more remote location.[49] In contrast to street print stalls, Demarteau’s descreet shop, accessible only to those who knew it, built up a sense of exclusivity. The English manufacturer Matthew Boulton notes for instance that ‘at Paris all their finest shops are upstairs’.[50] As a member of the Académie, an institution which forbade commercial activities, Demarteau may have also found a discreet commercial space more suitable than one open to the street.

FIRST IMPRESSIONS

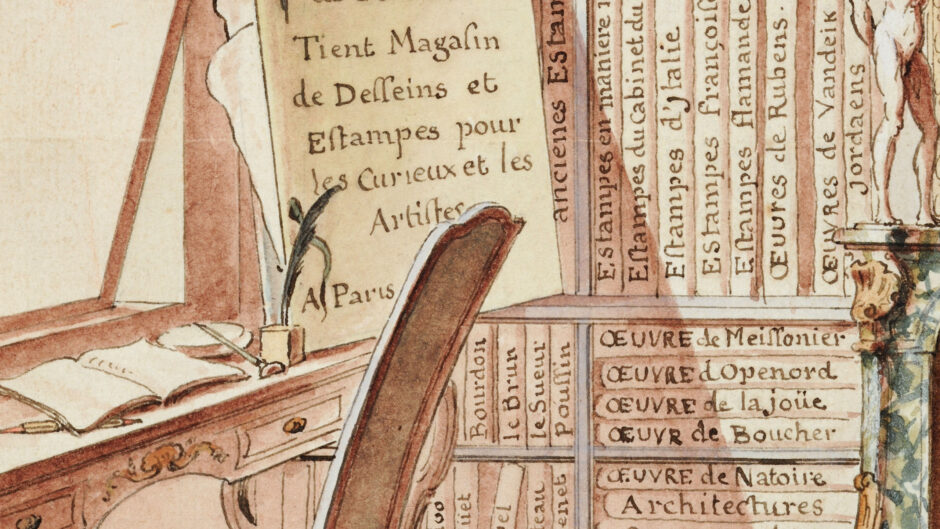

The salon scheme comprised a chimney piece, a fire screen with singeries, a now lost over-mantle including a large mirror surmounted by a floral painting and a second mirror hanging between two windows.[51] Evocative of the elaborate decoration of society rooms in hôtel particuliers, Demarteau’s salon would have felt familiar to an elite clientele whose interior followed a similar model. Accordingly, the idealised version of the printmaker Gabriel Huquier’s shop depicted on his trade card exhibited the furniture and decoration of a refined aristocratic interior. The elegant chimney mantel and desk show evidence that domestic furniture had the potential to increase a shop’s attractiveness (1749, Fig. 3). By visually pervading the composition with portfolios systematically arranged in shelves, Huquier’s card also advertised his shop’s wide range of supply. Unlikely to have been hidden behind such shelves, Boucher’s and Huet’s delicate painted panels implied a different staging of the prints in Demarteau’s shop. At Demarteau’s, actual prints – 1,500 to be exact – were stored on the third floor, in his workshop. [52] Thirteen prints under glass could also be found in the buffet in the kitchen near the salon. A few more, perhaps, were kept at hand in the rosewood Regency commode in the salon.[53] Instead of displaying an accumulation of prints to signal the abundance of commodities, Demarteau’s salon evoked the artwork for sale more indirectly, through subtle visual quotes. Indeed, many of the painted panel motifs such as the putti by Boucher and the doves by Huet were reproduced, nearly identically, in print by Demarteau.[54] Rather than a container of commodities for sale, the room embodied and exemplified the talent of the artists with whom Demarteau worked. The decorative scheme put the quality and prestige of the artwork forward as a commercial argument more than the quantity and diversity of prints for sale. Moreover, by exhibiting original autograph paintings by the artists whose work he reproduced, Demarteau emphasised his deep knowledge and long familiarity with Boucher and Huet’s original production, thus reinforcing his authority as a faithful reproducer of their work.

It is worth noting that, while the putti figures established Boucher’s reputation in the 1730s, four decades later, when he painted them for his friend Demarteau, the decorative motif had passed in fashion.[55]This suggests that Demarteau’s aim was to display motifs emblematic of the artists he worked with more than to decorate his interior in the latest fashion. Emphasizing the commercial specialisation of the shop in the works of these two eminent painters must have been crucial for Demarteau to distinguish himself from his ever-increasing competitors in the print market.[56] Similarly, the animal motifs on which Huet had established his reputation enabled clients to easily identify their author. By staging Demarteau’s links with academic circles, the painted panels subtly articulated what La Cloche had to offer: the experience of being part of an amateur community, rather than simply of buying prints.

Just as trompe l’oeil paintings did not actually deceive the eye, the small dimensions of the room and the reduced height of the panels barely exceeding that of a human body failed to reproduce a perfect illusion of a noble salon. In fact, it could be argued that the perception of their inadequacy provoked conscious attention, encouraging visitors to attend to the scheme in detail.[57] In this sense, the room appears to combine the features of a cabinet, a comfortable room of smaller dimensions dedicated to the study of the arts, and of a salon, a society room meant for polite sociability. The signs of the cabinet and the salon would have prompted a behavioural response, a disposition for conversation and artistic appreciation and for the informal dwelling it typically framed.[58]

TAKING A SEAT

By contrast to merchant-mercer shops, commercial spaces entirely dedicated to retail, La Cloche housed both the commercialisation and production of prints. The abbé Le Brun’s obituary, praising Demarteau’s attentive eye watching over his atelier, and Demarteau’s will mentioning three legacies to his ‘garçons (d’atelier)’, indicated that apprentices worked there, and perhaps lived in the rooms overlooking the courtyard and furnished with couchettes and pots of butter. [59] Moreover, the printmaker lived with the wife of his deceased brother Joseph, and their three children.[60] The shop thus constituted a hybrid space, where Demarteau lived with his family, produced and stocked prints with his apprentices, and hosted his refined clientele.

According to François Courboin, not all printmakers necessarily separated the commercial space of the boutique from their workshop, and when they did, the partitioning remained rather precarious.[61] However, Demarteau’s workshop, furnished with 1,500 prints and 563 copper plates, and a private oak wood printing press, a privilege granted to printmakers who were members of the Académie, occupied a distinct space on the third floor, separated from the boutique located on the second floor. [62] This indicates a sustained effort to contain the productive functions of La Cloche. As the concealment of his printing press by a screen also suggests, Demarteau sought to attenuate the problematic signs of craft and labour that might have threatened to disrupt the amateur narrative of taste and leisure. In Gabriel Huquier’s workshop too, a screen with elaborate illusionistic cartouches painted by Jacques de Lajoüe similarly served to flatter the eye and divert attention away from the mundane press it concealed behind. [63] Labour was reconfigured in the salon’s painted motif of the farmland, a site of agricultural production, featuring a rustic well, a watering can and a shovel. It shifted focus away from the tools and repetitive labour associated with craft to present a pastoral vision of natural productivity and wealth.

Judging from a 1754 detailed map of the Ile de la Cité by the abbé Delagrive, the shops on the rue de la Pelleterie were particularly narrow on the side of the Seine but twice as long as the shops on the bridges (Fig. 4). This suggests clients progressed inwards, from room to room, to reach the salon overlooking the river. Although evidence remains too scarce to establish the distribution of rooms, on the second floor, the excessive number of doors – at least four – in the small salon that could not have exceeded 25 square meters suggests a partitioning strategy to regulate circulation.[64] Painted in trompe l’oeil, the discreet doors disguised their presence, dissolving into the lavish decoration. While the central panels provided vast vistas into landscapes, the illusion of space created on the doors by the trellis work is simultaneously blocked by statues of putti erected in the foreground, forbidding entrance. Throughout his career, Boucher had capitalised on the putti motif for its wide decorative and commercial currency, but also, as Katie Scott has shown, for their metaphoric expression of artistic imagination.[65] Their presence on the doors, characteristic of Boucher, suggests that the doors were meant to be closed and the decoration to be seen and recognised. They regulated circulation by providing the printmaker with easy access to more private, domestic spaces, while confining customers in a restricted place until they might be invited into the attending salle overlooking the river and the bedroom, a room which also served to receive company in the eighteenth century.[66]

Enclosed in a dedicated space, customers were kept in a stationary position, enticing them to take a seat in one of the six green and grey velvet armchairs.[67] Compared to luxury objects and paintings, prints were more likely admired seated, since the supple paper required the horizontal support of a table. The seated position in the comfort of a chair enticed a longer encounter and invited a more personal and sensual experience with the artwork. Lavish decoration and comfortable interiors allowed shopkeepers to retain clients longer and increase their expenses. The mirror glass, mahogany and gilt wood reflecting and sublimating the commodities for sale at Le Petit Dunkerque, the merchant-mercer Granchez’s shop for instance, enticed the Baroness of Oberkirch to spend hours there. [68]

GETTING COMFORTABLE

While the location of the shop physically removed it from the street, on a thematic level too the representation of rural life on decorative panels of the salon removed it from the bustling, cramped and polluted reality of the rue de la Pelleterie. The dyers on the rue de la Pelleterie caused much pollution of the air and water and foreign visitors described the dark and stuffy streets of the Ile de la cité as the narrowest, gloomiest, and dirtiest streets of Paris. [69] How privacy and comfort contributed to amateur sensitivity is best illustrated by Alexander Roslin’s portrait of the amateur Barthélémy-Augustin Blondel d’Azincourt (1767, private collection) in the calm of his cabinet, who lent two thirds of his drawing collection to Demarteau.[70] The dark background, the desk on which his arm rests and the upholstered chair pushing him towards us, closely frame and confine him pictorially creating a sense of intimacy. Prolific self-expression is conveyed by the papers flowing out of the album and the pen in his hand. The confinement of the body in a comfortable room fostered self-awareness and the characteristic expression of subjectivity by amateurs.

Demarteau’s rustic landscapes populated by hens, chicks and rabbits created a peaceful retreat, favourable to amateur sensitivity. The perspectival construction of the panoramic landscapes, guiding the eye through framing trees or trellised pergolas onto the blue horizon, produced an immersive effect meant to transport visitors into a pleasing setting. Wilhelm even suggests that the ceiling might have been painted with green trellises and flowers.[71] The fiction of rusticity, amplified by the window overlooking the river, echoed landed nobility’s taste for pastoralism, which also appealed to a broader audience imitating high taste.[72] It mobilised a new sense of nature, sustained by the development of the landscape tableau and evolving practices of drawing from life outdoors.[73] According to the art historian Catherine Clavilier, the idyllic representation of rural life by elites served as reassuring images of stable and idealised social structures.[74]The rustic theme thereby helped secure and internalise amateur identities by anchoring visitors in a peaceful setting. Gathering clients in a shared rustic fiction referring to imaginary social types rather than their own actively harmonised a socially heterogenous clientele. The absence of historical and literary references ensured the paintings could speak to and consequently integrate a broad audience into Demarteau’s amateurcommunity.

It is striking to notice that while Boucher and Huet’s pastorals typically staged eroticised shepherds, the decorative landscapes are here unusually devoid of human figures. Painted human figures tended to be more expensive than animal or landscape paintings because they were thought to require more skill.[75] Their absence perhaps reflects Demarteau’s limited budget in comparison to Boucher’s habitual wealthy patrons. The panels also recall verdures, the tapestries produced by the Aubusson Manufactory in the 1750s and 1760s representing landscapes populated with exotic birds. [76] These cheaper tapestries were particularly appreciated by Parisian bourgeois who avidly collected them to hang in their interiors.[77] This suggests then that Demarteau’s shop also addressed the taste of a more modest audience than that advertised in the margins of his prints for instance.

The conspicuous absence of figures on the surface of the walls focused attention on the polite individuals in the room they circumscribed, and thus, perhaps encouraged a self-reflexive understanding of amateurs’s own identity. That the enveloping fiction of rusticity enhanced a sense of community is perhaps best illustrated by the draughtsman Jean-Michel Moreau’s drawing of a lunch (1765, Fig. 5) set in a decorative scheme strikingly similar to Demarteau’s salon. Enveloped by the trellises covering ceiling and walls, a group gathers around a table and speaker. Figures are turned inward, away from the window and towards each other, resting their arms on the table and chairs. The intimate ambiance and sense of community is built through the self-conscious withdrawal from the urban setting, still perceptible through the open window. The sense of community similarly conjured up by La Cloche was coherent with the private role of amateurs, involved in private taste communities, rather than the public sphere and providing personal advice and financial and intellectual support to artists for instance.[78] The schemes gathered and staged the community as the principal actor in the room.

MAKING CONVERSATION

Gilles Demarteau’s room shaped the amateur, not only because it looked like a noble interior, but because it operated like a salon and a cabinet, instigating the internalisation of amateur identity, and the externalisation of amateur social practices. If, according to Charlotte Guichard, amateurs constituted themselves in communities of equals, Demarteau’s choice to host his clientele in a salon, a society room which typically gathered individuals of equal status, seems judicious. [79] The salon setting attenuated the transactional nature of the relation between shopkeeper and clients. For instance, the inventory, listing armchairs, tables, and a commode, makes no mention of a counter such as the one recorded in Edmé-François Gersaint’s shop at the Pont-Notre Dame.[80] As opposed to the boutique, which polarised merchants evolving behind the counter and consumers moving in the room, the discrepancy in rank between the printmaker and his polite customers was virtually suspended. Identities circulated freely in a space, emulating society rooms planned for conversing amongst individuals of equal status.[81]

Additionally, the specificity of the printmaking trade, closer to retail than craft, allowed Demarteau to present himself as a merchant and connoisseur rather than a practitioner, which thereby narrowed the social gap separating him from his clients. Merchants provided valuable advice, shaped their clientele’s taste and developed close ties with them. Demarteau’s substantial collection of paintings, including four paintings by Eisen the elder and two paintings of monkeys by Peirotte, was exhibited throughout the rooms and informed artistic conversations. The two oval paintings by Boucher hanging in Demarteau’s bedroom for instance presented him as an avid collector himself, sharing his clientele’s taste.[82] The salon setting thus prompted polite conversation, rather than negotiation and inscribed Demarteau’s shop within an artistic milieu where taste, and polite sociability more than financial means were at stake.[83] The two Flemish déjeuner paintings hanging in the salon, likely between the painted panels, invited visitors to express aesthetic judgment.

PERUSING PRINTS

Parisian shops served not only as retail spaces, but also developed as alternative places where art lovers displayed, experienced and discussed artworks.[84] In the mid-eighteenth-century, art studios increasingly functioned as social sites for artists to host visitors and exhibit their work. The painter Jean-Baptiste Greuze for instance, boycotting the public salon of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, regularly hosted his clientele in his atelier at the Louvre.[85] The rise of ventes après décès, public sales of a collector’s goods and artefacts after their passing away, which took place in domestic interiors, accustomed amateurs to commercial logics infiltrating society rooms.[86] Charles-Nicolas Cochin’s frontispiece (1744, Fig. 6) for a sale captures how shopping for prints was conceived. At the centre of a cabinet, a group of amateurs gathers around a table. The amateur bending towards the portfolio suggests a complex process, involving several pairs of hands, to select the sheets, lay them out and distribute them, which engendered contact between amateurs. Laid out in the centre of the table, the prints are exposed to be seen from all angles convening the group around them. Observing, critiquing and manipulating prints constituted a social and cultural practice, and as such was best exercised in a society room.

In comparison to easel painting, admiring prints constituted a more intimate and less frontal encounter. The smaller format called for a close look. Impeding the possibility of walking at length, the cramped space of Demarteau’s boutique invited seated positions and groupings around prints, perhaps on the large table around which ten people could sit, and where Demarteau might have displayed a selection of prints.[87] Moreover, the room’s immersive imagery reflected in the mirrors, the cool light characteristic of northern-facing rooms, and the warmth of the lit fireplace, would have multiplied the sensual pleasure of manipulating prints.[88] In contrast to the cabinet, a space associated with a male audience, the salon welcomed both genders, and catered to Demarteau’s mixed clientele. As patrons, artists and collectors, women actively contributed to amateur culture and communities and thus constituted a strategic audience for Demarteau.[89] The numerous prints dedicated to women such as Madame de La Haye and Madame Blondel d’Azincourt, indicate he actively targeted a female audience.

As frames situating Demarteau’s artistic production, the painted decoration participated in sharpening visitors’ taste and visual skills. They prepared and conditioned the amateur eye by prompting visual recognition and attribution. For instance, the rabbits, sheep, and hens painted by Huet, and made familiar by the commercialisation of the Book of Animal Studies printed by Demarteau, were exhibited on the walls to be recognized and attributed.[90] On another level, the perception of the rustic landscapes in the background, while manipulating Demarteau’s pastoral, human and animal printed figures, might have helped his clientele anchor the reproduced studies by naturalising them. Indeed, the non-narrative and fragmentary nature of the unfinished figure studies reproduced by Demarteau presented serious obstacles to a non-practiced eye, as highlighted by Dézallier d’Argenville: ‘Great masters rarely finish their drawings, (…), which do not appeal to aspiring connoisseurs. They require something finished, which is pleasing to the eye’.[91] Highly aware of this issue, Demarteau intervened to contextualise them for a novice eye and added animals sharing striking similarities with those by Huet in the background of a female figure by Boucher for instance.[92] Similarly, the room’s decorative landscapes, populated with Huet’s animals evolving in receding space, might have functioned as backgrounds contextualising the prints’ unfinished and floating figures.

BUYING

While choosing prints, consumers were solicited to consider additional goods such as frames or protective devices which participated in the formation of connoisseurial skills. For instance, Demarteau sold his prints either bare or glued in the manner of proper drawings: he sold a print of four faces after Boucher 15 sols but, for those whose budget permitted, it could also be purchased ‘collé comme les dessins’ at 1 livre and 4 sols.[93] Moreover, the pendants Demarteau conveniently assembled emulated collectors’ practices but also enticed the purchase of two prints instead of one. Jean-Baptiste Huet’s Jeune Villageoise and François Boucher’s Un Polisson for instance were assembled as pendants.[94] Additionally, merchants typically offered glass protections at the shop for the preservation of client’s newly acquired print.[95] Publicly exhibited prints, such as Demarteau’s Lycurgue appearing at the 1769 salon, could see their price triple and reach twelve livres.[96] These different price points created by the diversity of options surrounding the print itself, diversified the printmaker’s offer and accommodated various budgets.

The socialised practices that developed around the purchase of prints armed clients with a better knowledge of the product and further facilitated their appropriation. For instance, fac-similé mats such as the one in The Education of Love (1761, Fig. 1), forming an oval vignette in a printed rectangular frame, familiarised buyers with the proper way of displaying a drawing in a private collection, while also providing a cheap ready-made solution for small budgets. Shopping, thus, initiated buyers into a practice of connoisseurship. Prints were not mere commodities as their purchase allowed customers to perform amateuridentity. Purchasing prints was less about ownership than practicing refined discernment and judicious acquisition.

A LASTING IMPRESSION

Likely offered after the purchase as a record or souvenir, trade cards were typically distributed at the shop to wrap objects.[97] Although it was likely designed by his brother Joseph, the Demarteau trade card seemingly insisted on creating a lasting memory of the engraver’s shop as a fashionable salon (ca 1750, Fig. 7). The airiness of the cartouche, the sophisticated acanthus leaves and wrapped garlands recall the decorative scheme clients had been invited to dwell in. The cursive letters extending into scrolls evoke manuscript writing and individual expression, a value praised by amateurs. By adopting the language of his clientele, Demarteau positioned his shop in the continuity of an amateur’s salon. The token maintained a sense of belonging to a shared community of taste generated by the shop. By creating a material bond between the shop and the amateur, the card encouraged customer loyalty and enticed them to come back to Demarteau’s to purchase more.

This article has demonstrated the agency of architecture in eighteenth-century Parisian shopping and artistic culture. La Cloche provides a valuable example of the role of shops in Parisian sociability and the art market. By initiating customers to amateur practices, the shop reproduced the amateur identity. It trained visual skills, encouraged conversations on art, taught how to select, manipulate and conserve prints, and integrated customers into an artistic network. Thus, more than a mere container, the shop embodied social relations, and functioned as an active agent in the formation of amateur communities. By positioning shopping for prints as a polite leisure, Demarteau’s boutique reconciled the commercial, cultural and social interests at play in the purchase of artworks. Demarteau’s decorated interior can be read as an example of semi-public spaces dedicated to art developing independently from artistic institutions.

Citations

- L’Avant-coureur (Published: 23 March 1761), 183-184.

- Sophie Raux, ‘La main invisible. Innovation et concurrence chez les créateurs des nouvelles techniques de fac-similés de dessins au XVIIIe siècle’, in Emmanuelle Delapierre and Sophie Raux (eds), Quand la gravure fait illusion : Autour de Watteau et Boucher, le dessin gravé au XVIIIe siècle, (Montreuil: Gourcuff-Gradenigo, 2006), 57-64.

- James Riley, ‘The Seven Years War and the French Economy’, in The Seven Years War and the Old Regime in France: The Economic and Financial Toil (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1986), 104-131.

- Joachim Christoph Nemeitz, Séjour de Paris (Leiden, 1718).

- Pamela Bianchi, ‘Les espaces d’exposition alternatifs du 18esiècle : entre sociabilité et contre-culture’, Dix-huitième siècle, 2018/1 (no.50), 85-97; Carolyn Sargentson, Merchants and Luxury Markets : The Marchands-Merciers of Eighteenth-Century Paris (London; Malibu (Calif.): Victoria and Albert Museum, 1996).

- Jacques Wilhelm, ‘Le Salon du graveur Gilles Demarteau peint par François Boucher et son atelier’, Bulletin du Musée Carnavalet, 1 (1975), 6-20.

- The two portraits are at the Musée Carnavalet (G.11477 and G.13617); The snuffbox is mentioned in Henri Bouchot, ’Les graveurs Demarteau Gilles et Antoine (1722-1802) d’après des documents inédits‘, La Revue de l’art ancien et moderne, 18 (1905), 102.

- Bouchot, 100-102.

- Bouchot, 100-102.

- ‘Fait pour plaire également aux jeunes artistes et aux amateurs’. L’Avant-coureur, (Published: 23 March 1761), 183-184.

- Charlotte Guichard, ‘Taste Communities: The Rise of the “Amateur” in Eighteenth-Century Paris’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 45, 4 (2012), 519-547.

- Charlotte Guichard, ‘Les “livres à dessiner” à l’usage des amateurs à Paris au XVIIIe siècle’, La Revue de l’Art, 143 (2004),49-58.

- Kristel Smentek, ‘An Exact Imitation Acquired at Little Expense. Marketing Color Prints in Eighteenth-Century France’, in Margaret Morgan Grasselli (ed.), Washington, Colorful Impressions. The Printmaking Revolution in Eighteenth Century France[exhib. cat.] (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2003), 9.

- La gravure supplée à l’inégalité des fortunes en satisfaisant les amateurs de toutes les classes’. François-Charles Joullain,Réflexions sur la peinture et la gravure, accompagnées d’une courte dissertation sur le commerce de la curiosité et les ventes en général (Paris, 1786), 31.

- Annick Pardailhé-Galabrun, La naissance de l’intime. 3 000 foyers parisiens, XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1988), 382.

- Cissie Fairchilds, ‘The Production and Marketing of Populuxe Goods in Eighteenth-Century Paris’, in John Brewer and Roy Porter (eds), Consumption and the World of Goods (London: Routledge, 1993), 228-248.

- Patrick Michel, Peinture et plaisir : les goûts picturaux des collectionneurs parisiens au XVIIIe siècle (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2010); Charlotte Guichard, Les amateurs d’art à Paris au XVIIIe siècle (Seyssel: Champ Vallon, 2008)

- Coquery, 2011; Natacha Coquery, La boutique et la ville: Commerces, commerçants, espaces et clientèles XVIe-XXe siècle(Tours: Presses Universitaires François Rabelais, 2000).

- Charlotte Guichard, ‘Valeur et réputation de la collection. Les éloges d’’amateurs’ à Paris dans la seconde moitié du XVIIIe siècle’, Hypothèses, 1 (2004), 33-43.

- For eighteenth-century theoretical writing on aristocratic domestic architecture, amongst others, see Jacques-François Blondel, Cours d’architecture ou traité de la décoration, distribution et constructions des bâtiments contenant les leçons données en 1750, et les années suivantes (Paris, 1771-1777); Charles-Etienne Briseux L’Art de bâtir les maisons de campagne(2 vols., Paris, 1743); Sophie Descat, ‘La boutique magnifiée. Commerce de détail et embellissement à Paris et à Londres dans la seconde moitié du XVIIIe siècle’, Histoire urbaine, 6 (February 2002), 69-86; For the architecture of domestic appartments which could be used as shops, see Jean-François Cabestan, ‘La naissance de l’immeuble d’appartements à Paris sous le règne de Louis XV’, in Daniel Rabreau (ed.), Paris, capitale des arts sous Louis XV. Peinture, sculpture, architecture, fêtes, iconographie (Bordeaux: William Blake & Co./ Art & Arts, 1997), 167-196.

- Minutes et répertoires du notaire Charles Boutet 29 août 1769 – 17 décembre 1789 (étude XLIV), Archives nationales (Pierrefitte-sur-Seine, 2013).

- Wilhelm, 6-20; Bouchot, 97-112; The Musée Carnavalet also keeps a transcription of Demarteau’s will, written on 11 May 1776 and given to his notary Monsieur Donon.

- Wilhelm, 8; Eugène Féral, Description d’une belle et importante décoration composée de 15 panneaux de diverses grandeurs par F. Boucher et H. Fragonard formant anciennement le salon de Gilles Demarteau (Paris: Dumoulin et Cie, 1890).

- Alfred de Champeaux, L’art décoratif dans le vieux Paris (Paris: Librairie générale de l’architecture et des arts industriels, 1898), 59.

- JF Hulot, Amalia Ramanankirahina, Conservation-Restauration des peintures du salon Demarteau Interventions sur les supports sur toile (September 2019), 2.

- Ewa Lajer-Burcharth and Beate Söntgen. Interiors and Interiority (Berlin; Boston: De Gruyter, 2016).

- Jean Chatelus, Peindre à paris au XVIIIe siècle (Nîmes: Edition J. Chambon, 1991), 36-42.

- L’Avant-coureur (Published: 25 May 1767), 321.

- Mercure de France (Published: January 1767), 164-165.

- Mathurin Roze de Chantoiseau, Essai sur l’almanach général d’indication d’adresse personnelle et domicile fixe, des six corps, arts et métiers… Pour l’année M. DCC. LXIX. (Paris, 1769), 110.

- ‘On trouve cette estampe chez lui, rue de la Pelleterie (…), et chez les marchands d’Estampes; prix 3 livres’. L’Avant-coureur (Published: 5 January 1767), 5.

- ‘Se vend à Paris, chez Demarteau, rue de la Pelleterie, à La Cloche’.

- Katie Scott, ‘Reproduction and Reputation: “Francois Boucher” and the Formation of Artistic Identities’, in Melissa Hyde (ed.), Rethinking Boucher (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2006), 91-132.

- Leopold de Leymarie, L’oeuvre de Gilles Demarteau l’aîné graveur du Roi (Paris, 1896), 6-7.

- The Getty Provenance Index.

- Germain Brice, Nouvelle description de la ville de Paris, et de tout ce qu’elle contient de plus remarquable, 3 (Paris, 1725), 2.

- Natacha Coquery, ‘Shopping Streets in Eighteenth-Century Paris’, in Jan Hein Furnée and Clé Lesger (ed.), The Landscape of Consumption: Shopping Streets and Cultures in Western Europe, 1600–1900 (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2014), 57-77.

- Pierre Coffy, ‘De la rue de la Pelleterie au premier marché aux fleurs de la cité. Récupération et transformation d’un projet urbain de l’Ancien Régime sous le Premier Empire’, Paris et Ile de France, Mémoires (Paris: Fédérations des sociétés historiques et archéologiques de Paris et Ile-de-France, 2017),7-41.

- Donald J. La Rocca, ‘Pattern Books by Gilles and Joseph Demarteau for Firearms Decoration in the French Rococo Style’, Metropolitan Museum Journal, 43 (2008), 141-155.

- ‘Apartement dudit Bauce, maître teinturier en chapeaux’, from the transcription of Demarteau’s inventory.

- Bouchot, 99.

- Natacha Coquery, ‘Hôtel, Luxe Et Société De Cour: Le marché aristocratique parisien Au XVIIIe siècle’, Histoire & Mesure, 10. 3/4 (1995), 339-69.

- David Garrioch, ‘House Names, Shop Signs and Social Organization in Western European Cities, 1500-1900’, Urban History, 1 (1994), 20-48.

- AN/Y/139-Y/146, AN/MC/ET/XXIV/138, MC/ET/XXXIV/104, MC/ET/XII/70

- According to Shepherd, Ancien régime shop signs represent a turn towards a modern conception of advertising. See, Harvey Shepherd, Memory, Enchantment, Desire: The Modernity of Advertising in Ancien Régime Shop Signs (MA Dissertation, Courtauld Institue of Art, 2018).

- L’Avant-coureur, (Published: 7 September 1761), 570.

- Coquery (2011), 144-148.

- ‘Dans la chambre d’entrée servant de magasin d’estampes, ayant vu sur la rivière, …la tenture de ladite pièce et les portes de communication de toile peinte representant des arbres et des osieaux, lapins et autres animaux, le lambris du pourtour du dit appt de treillage peint en vert’. Transcription of the inventory of Demarteau; Wilhelm, 6.

- Peter Fuhring, ‘The Print Privilege in Eighteenth-Century France I’, Print Quarterly, 2.3 (1985), 175-193.

- Cited by Sargenston, 133.

- Wilhelm, 8-9.

- Elizabeth M. Rudy, ‘On the Market: Selling Etchings in Eighteenth-Century France’, in Perrin Stein (ed.), Artists and Amateurs. Etching in Eighteenth-century France [exhib. cat.] (New-York: MET Publications, 2013), 40-67; Fuhring, 19-33.

- ‘Dans le buffet, linge. Treize estampes sous verre’. Transcription of Demarteau’s inventory, 2.

- See ‘L’Amour aux raisins’ at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, (Notice no.FRBNF44547628) and ‘Fontaine aux deux amours’ at the Metropolitan Museum of art (Accession Number: 602.924).

- Alastair Laing(ed.), François Boucher, 1703-1770 [exhib.cat.] (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987), 133-135.

- Jean Chatelus, Peindre à Paris au XVIIIe siècle (Nîmes: Edition J. Chambon, 1991), 36-42.

- Katie Scott, The Rococo Interior: Decoration and Social Spaces in Early Eighteenth-Century Paris (New Haven and London: Yale University, 1995), 115.

- On the space of the cabinet in society rooms, see Scott, (1995), 105; On social practices in the cabinet, see Alain Merot, ‘Le cabinet, decor et espace d’illusion’, XVIP siècle, clxii, 1989, 37-52.

- ‘Il ne fue pas seulement l’inspecteur des ouvrages faits chez lui. Il n’imita point ces hommes qui, comptant assez sur leur réputation, ne sont plus que les présents de leurs atteliers, & auxquels un coup d’œil semble suffire pour créer’ in Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun, Almanach historique et raisonné des architectes, peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs et ciseleurs (Paris, 1777), 147.

- Transcription of Demarteau’s inventory and Bouchot, 98.

- François Courboin, L’estampe française: Graveurs et marchands (Paris and Brussels: G. Van Oest & Cie, 1914), 2.

- Rudy, 40-67; Fuhring, 19-33.

- Katie Scott, ‘Screen Wise, Screen Play: Jacques de Lajoue and the Ruses of Rococo’, Art History, 36.3 (2013), 590.

- On the role of doors in understanding how space was occupied. Robin Evans, ‘Figures, Doors and Passages’, in Robin Evans (ed.), Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays (London: MIT Press, 1997), 55-91.

- Scott, 2006, 107.

- The manuscript transcription of Demarteau’s inventory mentions ‘une salle en suite ayant vu sur la rivière (…)’ followed by ‘dans la chambre à coucher, un trumeau de cheminée 28 pouces x 31 surmonté d’un tableau peint sur toile sur son parquet de bois peint en vert’.

- Transcription of Demarteau’s inventory, page 4.

- Sargentson, 1996.

- Coffy, 2017.

- Sophie Raux, ‘Le dessin à l’époque de sa reproductibilité technique. Diffusion et réception des fac-similés de dessins’, in Emmanuelle Delapierre and Sophie Raux (eds), Quand la gravure fait illusion : Autour de Watteau et Boucher, le dessin gravé au XVIIIe siècle (Montreuil: Gourcuff-Gradenigo, 2006), 107. The Swedish artist Alexander Roslin (1718-1793), member of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, painted the portrait of Barthélemy Auguste Blondel d’Azincourt (1719-1794) in 1767. The portrait is now in a private collection after Bruun Rasmussen Stockholm sold it on 19 November 1996 through the Konst & Antikviteter – Modern Konst, Grafik & Skulpturer sale.

- Wilhelm, 9.

- On the taste for pastoralism, see Scott (1995), 161-166; On the windows in the Demarteau salon, see Wilhelm, 9.

- Camilla Pietrabissa, From Perspective to Place: the Landscape Tableau in Paris (PhD Dissertation, Courtauld Institue of Art, 2018).

- Catherine Clavilier, Cérès et le laboureur. La construction d’un mythe historique de l’agriculture au XVIIIe siècle (Paris: Editions du Patrimoine CMN, 2009), 83.

- André Félibien, Conférences de l’Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture (Paris, 1667).

- Pascal-François Bertrand, Aubusson : tapisseries des lumières : splendeurs de la manufacture royale, fournisseur de l’Europe au XVIIIe siècle (Heule: Snoeck, 2013), 48-49.

- Bertrand, 48-49.

- Guichard (2012), 524.

- Guichard (2012), 532.

- Guillaume Glorieux, À l’enseigne de Gersaint. Edmé-François Gersaint, marchand d’art sur le pont Notre-Dame (1694-1750),(Seyssel: Champ Vallon, 2002), 163.

- Scott (1995),105.

- Bouchot, 100; Transcription of the Demarteau inventory.

- The transcription of Demarteau’s inventory mentions ‘deux tableaux peints sur toile representant un dejeuner flammand’.

- Guillaume Glorieux, ‘La boutique, un lieu alternatif de l’art au 18esiècle’, Dix-huitième siècle, 50 (January 2018), 99-111, 103.

- Jean-Marie Guillouët, Caroline A. Jones, Pierre-Michel Menger and Séverine Sofio, ‘Enquête sur l’atelier : histoire, fonctions, transformations’, Perspective, 1 (December 2015), 27-42, 39, http://journals.openedition.org/perspective/431, doi: http://journals.openedition.org/perspective/431, [Last accessed: 30 August 2021]

- Glorieux, 2018.

- ‘Une table à manger de dix convives’, in the transcription of Demarteau’s inventory.

- Since La Cloche was located rue de la Pelleterie, on the northern shore of the Ile de la Cité, and since the inventory mentions that the windows overlooked the Seine, we can infer that the room was northern facing.

- Heidi A. Strobel, ‘Royal “Matronage” of Women Artists in the Late-18th Century’, Woman’s Art Journal,2 (2005), 3-9.

- ‘Cinquième Livre d’études des animaux’.

- ‘Les grands maîtres finissent peu leurs dessins, (…) qui ne plaisent pas aux demi-connaisseurs. Ceux-ci veulent quelque chose de terminé, qui soit agréable aux yeux (…)’. Dezallier d’Argenville, Abrégé de la vie des plus fameux peintres (Paris, 1762), 38.

- Sophie Raux ‘Gilles Demarteau (1722-1776) dessinateur ? ou le paradoxe du graveur en manière de crayon’, in Dominique Cordellier (ed.), Huitièmes rencontres internationales du salon du dessin Dessiner pour graver. Graver pour dessiner (Dijon: l’Echelle de Jacob Paris : Société du Salon du Dessin, 2013), 55-63.

- L’Avant-coureur, (Published: 25 May 1767), 323.

- De Leymarie, 1896, 128.

- Joullain recommends to avoid purchasing prints under glass from merchants. Joullain,

- Raux, 2006, 112.

- Katie Scott, ‘The Waddesdon Manor Trade Cards: More Than One History’, Journal of Design History, 17.1 (2004), 91-104, 94.