Georg Scholz was a German artist affiliated with the Berlin Dada. In this article, I examine his work Industrial Farmers, which seems to challenge the Weimarian stereotype of the countryside as the romantic antithesis of the cold and superficial metropolis, otherwise known as the city-country dichotomy. Using Industrial Farmersas a case study, this article re-examines this cultural distinction and its pervasiveness in early twentieth-century Germany, whilst investigating how it contributed to the rise of conservative politics. By analysing the work’s complex cultural referents and by considering it in light of Dada montage, I explore how Industrial Farmers can be read as a multifaceted social critique. Employing Ernst Bloch’s concept of non-contemporaneity, the article argues that Industrial Farmers is representative of the ambiguity and paradoxical nature of how Weimar perceived the city-country polarity. The traditional distinction is diluted because both the peasantry and the urban bourgeoisie were united in their disillusionment with modernity, and both idolised the past. Yet it is reinforced due to the cultural dealignment between the peasantry and the urban left, the latter of whom viewed the former from a perspective that prioritised the modern and urban experience and consequently underappreciated the revolutionary potential of the rural demographic.

In February 1918, Richard Huelsenbeck returned to Berlin from Zurich. After spending time and taking inspiration from the Dada group that had formed at the Cabaret Voltaire in the Swiss city, the artist delivered a speech at the I. B. Neumann gallery. Titled the ‘First German Dada Manifesto’, Huelsenbeck’s speech marked the founding of ‘Club Dada’ in Germany. The speech outlined Dada’s goals by distinguishing the movement from previous artistic enterprises – Futurism, Cubism, and most notably, Expressionism. For Huelsenbeck and the Berlin Dadaists, Expressionism had failed to fulfil their ‘expectations of such an art, which should be an expression of [their] most vital concerns’. In contrast to the Expressionists who, in response to modern society’s cultural disenchantment, had striven for spiritual revitalisation through an abstract and apolitical art, the Dadaists were to show life’s ‘reckless everyday psyche’ in ‘all its brutal reality’: the movement was to be unmodulated and unflinching, ethically and culturally iconoclastic.[1]

This means that it was to be modern, and more specifically, urban. Although unacknowledged by Huelsenbeck in his speech, the ‘reckless everyday psyche’ was that of a metropolitan. In his 1903 essay ‘The Metropolis and Mental Life’, Georg Simmel examined the mentality of people living in big cities. He observed that, due to the overload of sensory stimuli in the metropolis, many city dwellers had adopted intellectualism and a blasé attitude as self-defence mechanisms, consequently only relating to each other superficially.[2] In fulfilment of their goal, the Dadaists featured this urban anima as their preferred subject matter. For example, George Grosz’s painting Metropolis (1916-1917, Fig. 2) shows a Berlin cityscape with a crowd filling the streets, a motif that he would return to throughout his career. In the painting, the metropolis is fundamentally chaotic, a vortex of industrial buildings, advertisement, and modern transportation. Consumed by the distracting pandemonium, people of varying occupations and social classes rush by one another without mutual acknowledgment. To underscore that the city had anonymised and desensitised its inhabitants, Grosz depicted the figures’ bodies as almost indistinguishable and their faces almost featureless. The city, as the painting demonstrates, swallows the individual up into an amorphous mass.

Compared to Simmel’s frequently cited analysis of the urban populace, the sociologist’s equally illuminating comments on the countryside have been relatively unremarked. Believing that the relative unimportance of the money economy in small towns and rural areas had led to a ‘slower, more habitual, [and] more smoothly flowing rhythm of the sensory mental phase’, Simmel argued that the psyche of the countryside ‘rests more on feelings and emotional relationships’.[3] For Martin Heidegger writing thirty years later, farmers, whose daily round was entrained by the seasonal cycle, epitomised this provincial mentality. In his 1934 essay ‘Creative Landscape: Why Do We Stay in the Provinces?’, the philosopher, partly echoing Simmel’s remark, criticised the superficiality of city life and romanticised farmers’ tie to the land.[4] This vision correlates to contemporary Expressionist representations of the countryside, which stand in sharp contrast to Grosz’s apocalyptic image of the city. Though the Expressionists, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, devoted much time to picturing the metropolis, they also took considerable interest in the countryside, which, for them, was a locus of transcendental encounter. For instance, Kirchner’s Sunday of the Mountain Farmers (ca 1929, Fig. 3) depicts a group of farmers gathering around the village fountain. The green hues of the farmers’ bodies merge them with the natural environment, reflecting their undeniable connection to the land, and their gestures and exchanged gazes indicate a stable rapport and emotional bond.

The accounts by Simmel and Heidegger, as well as the paintings by Grosz and Kirchner, contributed to crystallising the perception of a polarity between the cold, disenchanted, and superficial metropolis and the affectionate, tight-knit, and deeply-rooted countryside – a cultural stereotype prevalent in literary and visual documents of early-twentieth century Germany. Considering the Berlin Dadaists’ preoccupation with the urban psyche, Huelsenbeck’s accusation that the Expressionists had sought refuge in the spiritual and avoided the daily struggles of urban life was also representative of this stereotypical city-country dichotomy.

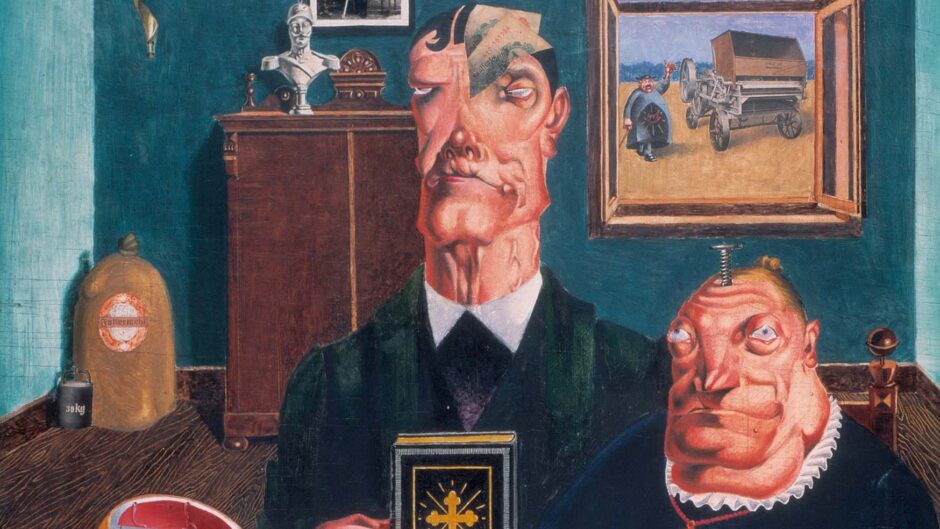

However, in a rare example of a Dadaist work that concerns itself with the rural population – Georg Scholz’s Industrial Farmers (1920, Fig. 1), which was exhibited at the First International Dada Fair in 1920 – this cultural distinction seems to collapse. Though existing literature on Industrial Farmers seldom goes beyond biographical, formal, or iconographical analyses,[5] the work sheds light not only on the nature of the perceived city-country polarity but also on the rise of conservative politics in Weimar Germany.

THE ORIGIN OF INDUSTRIAL FARMERS

Scholz was born in Wolfenbüttel to a middle-class family. After his father’s suicide, he was adopted by an affluent couple and started his artistic training at the age of eighteen. In 1915, two years after his graduation from the Grand Ducal Academy of Painting in Karlsruhe, he was conscripted into the German army. Scholz spent the subsequent three years fighting on both the Eastern and Western fronts until he was finally discharged in 1918 after being wounded by a hand grenade. Though he was promoted to the rank of Unteroffizier (subordinate officer) and received the prestigious Iron Cross Second Class for his contributions to the military, Scholz was disillusioned by the carnage of the war and, after his return to Germany, started increasingly steering towards left-wing politics. He joined the pacifist Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) in 1918 and became a member of the German Communist Party (KPD) immediately after its founding at the end of 1919. With artists he met at the Academy, such as Rudolf Schlichter, Scholz co-founded the artist group Rih in Karlsruhe in the hope of supporting a German Socialist revolution with art. He later joined the Berlin Novembergruppe, which had a similar belief in art’s revolutionary potential.

Through Schlichter, Scholz established contact with Grosz and John Heartfield, who were members of the Berlin Dada.[6] Like Scholz, many Dadaists had experienced the trauma of the war either in the trenches or in military hospitals. Believing that the war had resulted from Western civilizations’ persistent pursuit of rationalism, a fixation that had begun to develop in the Enlightenment era, the Dadaists responded to the annihilation of the First World War by assaulting reason with their art. Their preference for the irrational and the absurd was then charged with an extremely leftist, and sometimes even anarchist, political content.[7] The slogans of Berlin Dada resonated with Scholz, and the artist soon started actively participating in the group’s activities. He contributed writings and illustrations to the Malik-Verlag publication Der Gegner, edited by Heartfield’s brother and fellow Dadaist Wieland Herzfelde.[8] Scholz also began to adopt a politically sensitive Dadaist aesthetic in his works, of which Industrial Farmers is a prime example.[9]

In this work, members of a peasant family, wearing their Sunday best, gather around the table in their house. The father is seated in the middle, clutching a Bible to his chest, while banknotes issue from a scar on his forehead. His authority in the family is suggested not only by his compositional centrality but also by the cup in front of him, which is printed with the phrase ‘Dem Hausvater (To the paterfamilias)’. On the right, the mother, with a bolt sticking out from her forehead, cradles a piglet. Her tight mesh gloves and the ruffles of her dress emphasise her distorted body. On the left, the son, who appears to be mentally disabled, attempts to blow up a frog that he has pinned down on the table. The phrase ‘Patent-Kurzstrohzuführung (Patented short straw feed)’ hangs from his open skull, replacing his brain. Scholz’s grotesque depiction of the family contrasts with his veristic portrayal of their surroundings. On the one hand, the glass butter spinner in the lower right corner, the flypaper hanging from the ceiling,[10] and the stapler on the table signify the arrival of modern technology in the farmers’ household. These objects are analogous to the combine harvester outside the window, which represents the dawn of mechanised farming. On the other hand, the two-door wooden storage cabinet in the rear of the composition, which was known as a Biedermeier vertiko and which had become popular in mid-nineteenth-century Germany, as well as the overflowing sack of animal feed, the huge quantity of which is signified by the thirty-kilogram weight, are reminders that the family still retains a rather traditional way of life.

According to Scholz’s student Manfred A. Schmid, Industrial Farmers was the result of a painful encounter between the artist and a peasant family.[11] After the First World War, farmers were financially well-off compared to other sectors of society. They were self-sufficient and had an abundancy of produce, which they would sell and barter for other valuable objects, such as furs, carpets, and jewellery. As a result, they were able to quickly accumulate material wealth. However, when Scholz, suffering from excruciating hunger while returning from the war, attempted to purchase food from a relatively affluent peasant family, he was shunned – the family pointing him in the direction of a compost heap.[12] This humiliating experience prompted the artist to create Industrial Farmers, a work that not only criticises the unfriendliness of the peasant family that he met but also, implicitly, pours scorn on all farmers who, during the war, acquired a fortune through the plight of the urban population instead of via agricultural work.[13]

Nevertheless, it was not solely the peasantry’s opportunism and selfishness during wartime that Scholz critiqued in Industrial Farmers. Believing in the work’s effectiveness and its appeal to left-wing sympathisers, Heartfield and Grosz wrote to Scholz enthusiastically on 16 July 1920, insisting that the artist send Industrial Farmers to Berlin in preparation for the Dada Fair and claiming that this ‘important’ piece of art would cause a widespread celebration after its exhibition at their ‘biggest show on earth’.[14] Scholz’s multivalent critique of Weimar Germany in Industrial Farmers, which was apparent to his Dadaist peers, and his perception of farmers’ role in society become explicit when the work is considered in light of contemporaneous political thought and the Berlin Dadaists’ artistic practices.

DISCOURSES OF PROVINCIAL CONSERVATISM

To understand the basis of Scholz’s multifaceted critique in Industrial Farmers, as well as the broader reasons for his negative portrayal of the peasantry, it is necessary to contextualise the work in the conservative discourse at the time. In Weimar Germany, the perceived conservatism of farmers was a theme in many writings across the political spectrum. In 1928, almost a decade after Scholz’s work, the left-wing journalist Kurt Tucholsky noted the still overt conservatism of agricultural communities in his article ‘Berlin and the Provinces’:

As for the republican idea (in the attenuated form in which it is produced in Germany), it must be said that it is to be found only spottily out there in the countryside […] One has to read the minutes of a meeting of the Republican Press Association to comprehend the extent to which republicans are merely tolerated.[15]

Similarly, citing the resurgent popularity of nostalgic novels in rural areas, the conservative essayist Wilhelm Stapel wrote in his 1930 article ‘The Intellectual and His People’ that the rural population opposed ‘deracination’ and were at odds with metropolitan ideas. Criticising intellectuals who tried to impose Berlin on the German landscape, he claimed, ‘the demand of the day can be summarised like this: the rebellion of the countryside against Berlin.’[16]

The provincial conservatism that Tucholsky and Stapel observed is implicit in how Scholz depicted the interior within Industrial Farmers. Its Biedermeier décor, considered in terms of the contemporary discourse of Heimatschutz (homeland protection), reveals an aesthetic link between villages and conservatism. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, the Bund für Heimatschutz (Association of Homeland Protection), with architect Paul Schultze-Naumburg as its president, attempted to address conflicts between tradition and modernity in twentieth-century Germany. On the one hand, they advocated for the use of new industrial materials and a commitment to contemporary life. On the other, they stressed the need to maintain national traditions and Germanic indigenous culture, mainly through the protection of the rural landscape and its historical sites. To reconcile these seemingly contradictory issues, the architects of Heimatschutz sought solutions by looking back to Biedermeier architecture and design, an interest in which was reignited by the publication of Paul Mebes’s extremely popular book, Um 1800 (‘Around 1800’) in 1903. For these architects, Biedermeier architecture would not only preserve German heritage by employing indigenous materials and evoking vernacular building types of the countryside but also ‘[reveal] an attitude that considered formal and aesthetic qualities to be of value […] in relation to contemporary life’. Based on the Biedermeier model, Schultze-Naumburg produced a building manual, Der Bau des Wohnhauses (‘The Construction of the Residential House’), the instructions of which, if followed attentively, were supposed to result in an ideal architecture.[17] However, even Heimatschutz building projects that more successfully integrated modern needs and traditional values, such as Heinrich Tessenow’s series of small housing settlements designed to accommodate urban industrial workers in various Kleinstädte (small towns), could not escape their conservative core.[18] As Michael Hays argued in an article on Tessenow’s works, such architecture merely represented a new system of communication that:

[…] attempts to reinstate vestiges of the kind of hegemony associated in the past with the traditional order. This new order surreptitiously reproduces the closed and tightly knit hierarchies by which a truly rooted culture legitimates, differentiates, or interdicts, in an effort to provide what Edward Said has called a restored authority.[19]

This connection between Biedermeier architecture and provincial ‘hegemony’ finds its pictorial manifestation in Scholz’s Industrial Farmers.

The Heimatschutz discourse, as well as Stapel’s favourable accounts of provincial conservatism, is part of the broader discourse of the conservative revolution in Germany at the time. After the First World War, several right-wing writers voiced their discontent with the political situation of the Weimar Republic, which they considered the result of Germany’s enfeeblement by military defeat, the humiliating Treaty of Versailles, the economic crisis, the emergence of mass culture, and political liberalism. Criticising ‘rationalised’ politics, contemporaneous right-wing commentators called for a new Germany characterised by state unity and military strength. The Austrian writer Hugo von Hofmannsthal referred to this movement as a ‘conservative revolution’, and this term was later widely adopted by historians of the period. An important aspect of the conservative revolutionary ideology is the denunciation of what its sympathisers regarded as ‘the boredom and complacency of bourgeois life’ and the yearning for ‘renewal in an energising “barbarism”’.[20] Many writers associated with the movement found this ‘barbarism’ in the rural peasantry. Though intellectuals themselves, they attacked intellectualism in its metropolitan form, advocating for a knowledge gleaned from experience, such as that they believed was possessed by farmers.[21]

One of the most influential thinkers associated with the conservative revolution was Oswald Spengler, who traced the historical development of Western societies in his book The Decline of the West (1918). In this notoriously popular work, Spengler juxtaposed the circulation of blood and money. For him, with the advent of sedentary agriculture, farmers established their roots, and the ‘circulation of blood’ occurred. According to the writer, blood is the:

[…] symbol of the living. Its course proceeds without pause, from generation to death, from the mother’s body in and out of the body of the child […] The blood of the ancestors flows through the chain of the generations and binds them in a great linkage of destiny, beat, and time.[22]

However, under capitalism, this genealogically informed circulation was replaced by the circulation of money which, in turn, and as typified by the metropolis, created an alienated world of abstract exchange and finance.[23] Spengler considered modern cities as dominated by Gelddenken (money thinking) that was devoid of vitality. For Spengler, cities were the last stage of cultural decline, which he named Zivilisation.[24] Like his fellow writers of the right, Spengler reiterated and politicised neutral distinctions that were first established by previous commentators, such as Simmel. It was also within this framework of conservative revolutionary thinking that Heidegger, a conservative philosopher, voiced his preference for the country over the metropolis.

SCHOLZ’S MANIFOLD SOCIAL CRITIQUE

Scholz’s disfiguration of the peasantry in Industrial Farmers should be considered in light of the contemporaneous conservative discourse that stressed the dichotomies between Kultur and Zivilisation,Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft, experience and intellectualism, concreteness and abstraction, life and death, as well as the over-laying of these dichotomies onto a pre-established contrast between the metropolis and the countryside. In the work, the artist critically evoked the conflation of Prussian militarism with patriarchal authoritarianism and religion and utilised the subject of farmers as a vehicle for his critique of these intertwined conservative ideologies.

On the wall of the household in Scholz’s work, the photomontage is in the tradition of popular military memorial portraits of the time. As Dadaist Raoul Hausmann recounted:

In nearly every house there was to be found hanging on the wall a colour lithograph depicting an infantryman in front of military barracks. In order to render this memento of the military service of a male member of the family more personal, a portrait photograph of the owner of the martial image had been glued in place of the head in the lithograph.[25]

Instead of being pictured beside military barracks, the memorialised soldier in Scholz’s work, whom Brigid Doherty has considered a possible stand-in for the farmers’ firstborn son who had sacrificed his life during the war,[26] stands in a room like the one occupied by his family. Along with the bust of the bygone Kaiser who had initiated the war, this portrait suggests the peasant family’s jingoistic commemoration of war and support of the Prussian army. Scholz further emphasised the family’s military affinity by alluding to war injuries. The father’s scarred face alludes to the disfigurements suffered by war veterans, a reading supported by the fragmented banknotes in his skull that resemble lodged shrapnel. Moreover, the piglet in the peasant woman’s hands recalls the contemporary saying Frontschwein (‘hog of the front’), a term used to describe long-serving soldiers in the Great War. The reference indicates that this family is prepared to dedicate its offspring to the fatherland in wars to come.[27] The soldier in the memorial portrait wears the uniform of a subordinate officer,[28] the same rank that the artist achieved during his military service. But in contrast to the monochrome photomontage, Scholz painted the uniform of the commemorated officer in gaudy colours to not only scorn the farmers’ glorification of militarism but also mock his own military service.

The support for militarism amongst the agricultural population that Scholz indicated in his work also underscores the link between war, nationalism, and masculinity in Weimar Germany. As George Mosse has pointed out, the ideal masculinity in post-war Germany was marked by ‘a new dimension of brutality’.[29] With the First World War, the belief that military drills and combat would strengthen the male body, and that war, by testing both young men’s dedication to the fatherland and their willpower, would aid maturation, became crystallised. As a result, in the Weimar years, ‘the German soldierly type’, a trope of masculinity closely tied to nationalism, discipline, and aggression, became the norm.[30] This ‘brutalisation’ of masculinity, in Mosse’s words, manifests in Industrial Farmers not only as visual references to the farmers’ loyalty to the Prussian army but also as the father’s absolute command over his family, as suggested by his central position and the inscription on his cup. The patriarch’s authority becomes even more apparent when considering that his family members are represented as his mental and physical subordinates. The son’s distorted face, his dripping snot, and his mindless act of cruelty are indicative of “retardation” – a mental deficiency and immaturity as it was then conceived, whilst the peasant wife has, quite literally, a screw loose in her head. In this sense, the father demonstrates his manliness by commanding his household, while brooding on his nation’s future military conquests beyond the confines of the domestic interior.

References to German Protestantism in Industrial Farmers further complicate Scholz’s critique. With her blue dress and motherly posture, the peasant woman is a satirical iteration of the Virgin Mary. The printed publications strewn on the table, with the words ‘Himmelwärts (heavenward)’ and ‘Kinderherz (heart of a child)’ legible, form an ironic juxtaposition with the demonic cruelty of the peasant child. Outside the window, the belly of the priest next to the combine harvester is depicted with X-Ray vision. The inside of his body is empty except for a floating grilled chicken surrounded by divine rays, symbolic of ecclesiastical gluttony and, according to Sonja Grunow, a parody of the Christian motif of the sacred heart.[31] Inside the house, the father, with the Bible in his hand, also plays the role of a hypocritical priest, whose religious piety is only a guise for greed. As Matthew Biro has noted, German Protestantism at the time ‘provided German nationalism with spiritual underpinnings’ and ‘was associated with the conservative values of the Prussian monarchy’.[32]For Scholz, his personal encounters with religious authorities during the war further cemented his disparaging view of organised religion. In ‘Deutsche Dokument (German document)’, a satirical account of his war experience published in Der Gegner in 1920, Scholz recounted incidents of clerical corruption and exploitation, as well as the clergy’s complicity in promoting militarism. According to the artist, while emaciated soldiers like himself were restricted to pearl barley for every meal, priests gorged on roast goose and champagne. Quoting a speech given by a pastor to the hungry public, Scholz detailed how the pastor used religious rhetoric to convince believers to donate their savings into war bonds, thereby satisfying ‘God’s servant’ Paul von Hindenberg, the high commander of the Prussian army.[33] Thus, with the conflation of religion with greed and deviancy, Scholz’s Industrial Farmers demonstrates the artist’s critique of the interwoven ideologies of militarism, the Prussian monarchy, nationalism, and Protestantism, as well as his understanding of the agricultural population’s endorsement of these ideas.

Nevertheless, apart from being politically conservative, the farmers that Scholz depicted are also corrupted by industrial capitalism, the criticism of which constitutes one of the most essential aspects of the multifaceted critique contained within Industrial Farmers, especially when considering Scholz’s involvement with the KPD. As the staple symbol of capitalism, the money in the father’s head could have several connotations. In one sense, it implies that the modes and desires of the capitalist have come to dominate the mind of the rural population. In another, it is Scholz’s sarcastic comment on inflation and the looming economic catastrophe. For the work, Scholz cut up Darlehnskassenscheine (State Loan Office notes) and pasted them onto the painted surface. At the beginning of the First World War, instead of financing the war through taxation, the German Reich tackled the problem by issuing war bonds and printing more money. In addition, the Reich encouraged citizens to exchange their coins for Papiermark (paper notes), so that gold and other metal could be used for the war effort.[34] It was in this context that, in 1914, the Reichsschuldenverwaltung (Reich Debt Administration) first issued Darlehnskassenscheine based on the designs of former Prussian banknotes. Though, in theory, they were not official banknotes and were not based on the gold standard, they were recognized all over Germany as an acceptable form of payment. Eventually, the excessive issuance of Darlehnskassenscheine and other forms of unofficial currency in Germany during this time resulted in their gradual devaluation and culminated in the hyperinflation of 1923, when they became essentially worthless.[35]Thus, given Scholz’s war trauma and socialist stance, the cutting-up of Darlehnskassenscheine for Industrial Farmers is symbolically significant. It was a retaliative act of violence against the Kaiserreich, the authority that had sold the country into war and planted the seed for the forthcoming economic catastrophe. In creating Industrial Farmers, Scholz cut into the Kaiserreich both actually and metaphorically, incising at the notes’ issuing authority and the prime feature of their design.

Objects that Scholz placed in the heads of the son and the mother also merit a more detailed analysis. The son’s brain, for instance, has been substituted for the phrase ‘Patent-Kurzstrohzuführung’. This cut-out phrase and the image of the combine harvester may have derived from the same source – a contemporary advertisement for the industrial farming machine. In fact, this seemingly peculiar phrase, meaning ‘patented short straw feed’, refers to the mechanics of the combine harvester, during which the machine feeds harvested crops to the sieve. The action of the son, feeding air into the frog that he is torturing, parallels this mechanism. Like the combine harvester outside the window, he operates mechanically. He has been desensitised and stripped of human agency – in other words, he has been rendered an automaton. His body, connected to the frog by a straw, acts according to the instruction implanted in his head, almost as if printed code were being fed into the machine. Similarly, the loosened screw in the peasant woman’s head suggests that industrialisation has unhinged her, transforming her into a mindless mechanical being. Through the inclusion of these appendages, Scholz has presented the family members as cyborgs, which Biro has defined as human-machine or human-animal combinations.[36] The artist has visualised industrial capitalism’s domination and distortion of the agricultural body and mind. As Karl Marx theorised, modern industrial processes have alienated the mother and the son from their existence as humans, making them incapable of recognising their condition or effecting change.

The plight of the tortured frog also has Marxist undercurrents. For Marx, under capitalism, animals became not only the property of humans but also their apparatuses, which they exploited as a means of production. In turn, the exploitation that caused animals to suffer – which, according to Marx, created an ‘alienated speciesism’ – was analogous to the plight of exploited workers.[37] In the context of Weimar Germany, the miserable experience of the frog correlates to that of urban proletarians, who were treated as means for capitalist gain. The peasant boy torturing the frog as a part of a mechanical process, then, becomes an exploiter in the capitalist system, whose brutality Scholz laid bare in his work. By visualising, albeit satirically, the processes and effects of capitalism upon Weimar society, Scholz illustrated the transformation of a peasant family into the eponymous ‘industrial farmers’ of the artwork.

THE POLITICS OF DADA MONTAGE

The work’s title also alludes to Scholz’s use of the montage technique. As Brigid Doherty has suggested, by referring to the peasant family as ‘industrial farmers’, Scholz referenced ‘a contemporary definition of the word montage as a technique for assembling or mounting machine parts in modern industry’, thus creating a link between his creative process and industrial production.[38] In Scholz’s work, there are numerous elements of montage, or in other words, fragmented and reassembled materials pasted onto the painted surface. These include the newspapers, the thirty-kilogram weight, the phrase ‘Patent-Kurzstrohzuführung’, the memorial portrait, the money, and the combine harvester. In fact, apart from its visual elements’ rich cultural indexicality, the efficacy of Scholz’s social critique in Industrial Farmers is also dependant on its technique.

Montage was the Berlin Dada’s medium of choice. In the ‘First German Dada Manifesto’, Huelsenbeck stated, ‘[…] the highest art will be that which in its conscious content presents the thousandfold problems of the day, the art which has been visibly shattered by the explosions of last week, which is forever trying to collect its limbs after yesterday’s crash.’[39] In decontextualising and reassembling images and texts, montage fits Huelsenbeck’s criteria of the ‘highest art’ set out in his revolutionary call. Its ‘conscious content’ was the re-collation of fragments produced by shattering a prior whole. In a presentation following Huelsenbeck’s speech titled ‘The New Material in Painting’, Raoul Hausmann further commented on montage’s transformative power for artists and the audience. For him, montage was not merely the artistic counterpart of industrial production. Instead, with the inclusion of photographic illustrations from print media, or ‘real material’, montage also simulated the cinematic experience, allowing the Dadaists to create ‘the newest art of a progressive self-representation captured in motion’. This art would make the viewers recognise their ‘real situation’ in an ‘embodied atmosphere’, therefore establishing a new relationship between art and its beholders based on authenticity and reciprocity.[40] In this sense, Dada montage, in its method, fragmentary form, and implication of corporeality, responded to the situation of contemporary viewers – it mirrored the disorder of the age. It represented the viewers’ fragmented experience that had resulted from the trauma of the war, the alienating effects of capitalism, the economic crisis, and political turmoil. Though politically subversive, it was an antidote that was homeopathic in principle: it treated like with like.

One aspect of Dada montage that represents the audience’s ‘embodied atmosphere’ mentioned by Hausmann is its evocation of laughter through grotesque humour. Wolfgang Kayser has defined the grotesque as ‘that which was familiar and homely, [and that] has suddenly revealed itself to be strange and uncanny’.[41]This juxtaposition is apparent in Scholz’s Industrial Farmers, which shows a peasant family with distorted physiques, that is, the ‘uncanny’, sitting in a realistically portrayed domestic interior, or the ‘homely’. For Kayser, the grotesque is also manifest in cyborgs, which, as fusions of the mechanical and the organic, are ‘petrified bodies-cum-personifications of death’.[42] In this sense, the farmers in Scholz’s work, whom the artist turned into cyborgs by combining them with cut-and-pasted objects that allude to industrial production, are embodiments of the grotesque – they are intended to elicit from the viewers a visceral feeling of horror and disgust. Nevertheless, in tandem, the cyborgian farmers are also intrinsically humorous. In his 1900 essay on laughter, Henri Bergson constructed the cyborg as a comedy trope. With their ‘illusion of life and the distinct impression of a mechanical arrangement,’ to quote Bergson, cyborgs ‘are innumerable comedies, in which one of the characters thinks he is speaking and acting freely […] whereas, viewed from a certain standpoint, he appears as a mere toy in the hands of another, who is playing with him’.[43] In this sense, the machine-like farmers in Scholz’s work, as puppets of industrial capitalism, produce in the audience a simultaneous feeling of both horror and pleasure. Thus, by evoking these reactions in the viewers and by rendering its subjects as devoid of human agency, Industrial Farmers ‘affirms the viewing body as it negates the laughter’s target’,[44]which, in this case, is the peasant family that Scholz criticised.

Nevertheless, Industrial Farmers differs from most examples of Dada montage in that it combines montage with oil painting.[45] Considering the content of Industrial Farmers and the politics of Dada, Scholz’s choice of medium created an added dimension to his critique. As Sabine Kriebel has argued, the political potency of grotesque humour in montage is inseparable from the medium’s ‘holy hate (heiliger Hass)’, a central aspect of left-wing political aesthetics. This term was coined by Marxist philosopher Georg Lukács in 1932. For Lukács, ‘holy hate’, or ‘the justified anger of the oppressed masses against the ruling system’, distinguishes political from superficial humour. This ‘class-conscious form of expression’ aiming at ‘the social conditions, crimes, and inequities of capitalist society’, Lukács explained, is based on a dialectical relationship between real experience and the sensuality of fantastical grotesque humour, which he summarised as an ‘uncanny liveliness (unheimliche Lebendigkeit)’.[46] Scholz’s fusion of media in Industrial Farmers allowed him to juxtapose the real and the fantastical. Though the marriage of montage and painting in the work appears seamless, appropriated images from circulation allude to material reality, or the viewers’ embodied ‘liveliness’, whereas their manipulation and re-collation, as well as the painted portions of the work, allow the artist to exaggerate the uncanny and his grotesque humour by distorting the farmers’ bodies and creating a fabricated domestic interior. In this sense, the combination of montage and painting accentuates the effect of the work’s ‘holy hate’, which, in this case, is directed at the farmers who, for the artists, were accomplices in the capitalist system.

Scholz’s fusion of media also symbolically assaults the bourgeois mode of representation. His depiction of farmers defied the bourgeois standard of beauty. Moreover, the artist directly superimposed elements of montage, a creative form associated with the artistic avant-garde and left-wing politics, onto an oil painting, an artistic medium traditionally associated with the bourgeoisie. By covering up parts of the painted surface with cut-and-pasted elements, Scholz metaphorically asserted the supersedence of bourgeois art and values by those favoured by the political left.

PROBLEMATISING PROVINCIAL EMBOURGEOISEMENT

Scholz’s challenge to the bourgeois mode of representation is also evident in Industrial Farmer’s reference to the tradition of Biedermeier family portraits. The development of Biedermeier art is inseparable from the emergence of the urban middle class which, due to rapid industrialisation and urbanisation, grew substantially after the Napoleonic Revolution.[47] The term Biedermeier itself carries bourgeois connotations, as it was derived from the name of a fictional schoolteacher who is satisfied with his middle-class lifestyle. As art patronage shifted from the preserve of the aristocracy and the church to the hands of the urban bourgeoisie, naturalistic portraits in bourgeois interiors became one of the most prevalent artistic genres.[48] For instance, the domestic interior, the figures’ dress, and the central placement of the father in The Begas Family (1821, Fig. 4) by the celebrated German artist Carl Joseph Begas (1794-1854) are evidently parodied in Industrial Farmers. In contrast to Begas’s naturalistic portrayal of the sitters and his emphasis on their strong familial ties evidenced in the exchange of the family members’ gazes, Scholz distorted the appearance of his figures and their gazes, thereby demonstrating the family’s indifference to one another. And it is not solely faith in one’s own family that has been lost. In Scholz’s work, the religious painting above the vertiko has been replaced by a military portrait, and the church outside the window in Begas’s painting, symbolic of the bond between family and faith, has made way for the corrupted priest and combine harvester: militarism and industrialism have become the farmers’ new religion. By alluding to Biedermeier portraits such as those of Begas and simultaneously subverting this artistic tradition, Scholz not only indicated that the peasantry has merged with the urban bourgeoisie but also created a new image of the middle class – cold, conservative, and individualised by industrial capitalism.

Scholz’s conflation of the peasantry and the urban middle class, as well as the implied visual argument that agricultural families had been corrupted by industrial capitalism, results in the seeming collapse of the stereotypical city-country dichotomy in Industrial Farmers. Apart from his belief in farmers’ conservatism and their complicity in society’s corruption, his grotesque portrayal of them is also a product of his disappointment in their embourgeoisement. The rural population, as perceived by Scholz, was transformed by industrial capitalism and, as a result, became homogenous with the urban bourgeoisie, the ideological enemy that the Dadaists attempted to ridicule in their works. The poignancy of his attack on the farming community, in the same manner of the Dadaists’ caricature of the bourgeoisie, was even recognised by the Social Democrats, as evinced by Scholz’s interrogation regarding Industrial Farmers in the Reichstag after its exhibition at the Dada Fair.[49]

Nonetheless, the provincial embourgeoisement that Scholz conveyed in his work still merits further analysis. For the artist, conservative ideologies and the modes of industrial capitalism were integrated in the peasantry in the worst possible way – the agricultural population succumbed to capitalist money thinking and the convenience provided by modern technologies yet remained politically conservative. To examine the accuracy of this perception, it is productive to employ Ernst Bloch’s concept of non-contemporaneity.

At the beginning of his 1923 essay, ‘Summary Transition: Non-Contemporaneity and Obligation to Its Dialectic’, Bloch introduced the concept of non-contemporaneity:

Not all people exist in the same Now. They do so only externally, through the fact that they can be seen today. But they are thereby not yet living at the same time with the others. They rather carry an earlier element with them; this interferes. Depending on where someone stands physically, and above all in terms of class, he has his times.[50]

Industrial Farmers embodies Bloch’s concept of temporal and cultural asynchrony in many aspects. Its oxymoron-like title juxtaposes ‘industrial’ and ‘farmers’, a pre-industrial occupation. Montage is also a temporally ambiguous artistic technique, as images from different times are placed on the same pictorial plane, and Scholz’s combination of this modern medium with oil painting joins forms of artistic production that are representative of different historical periods. Moreover, the depicted interior, containing both modern gadgets, such as the stapler and the butter spinner, as well as traditional elements, such as the Biedermeier vertiko and the feed sack, is also non-contemporaneous.

However, despite potentially appearing otherwise, the introduction of modern technical appliances to the peasant family in Industrial Farmers is neither a fundamental change nor an indication of the dominance of industrial capitalism. According to Bloch, it was hard for machines to replace farmers in their occupation because farmers still retained ownership of their means of production: agricultural machines only functioned as aids – that is, as means rather than ends in themselves. Also, due to their communal form of production, economic differences between farmers remained small, and even the poorest peasants still possessed private property. Furthermore, because agricultural production originated in pre-capitalist times and still depended on the soil and the seasonal cycle, farmers remained connected to an older lifestyle that was at odds with urbanisation.[51] Bloch argued that ‘the farmhouse, despite all capitalist forms, despite all ready-made clothes and urban products, is Gothic in outline and aura even today’.[52] Therefore, farmers were rather insusceptible to the influence of industrial capitalism, and their interest in profits was only due to their economic sobriety and traditional excellence at calculation.[53] Consequently, the integration of the old and the new in the depicted interior is superficial, and it only evinces the peasants’ temporary material adaptation to modernity. The collection of objects in the depicted household that resembles the bourgeois interior of the Biedermeier era also suggests farmers’ link to traditions in and of itself. Remarking on the nineteenth-century bourgeois interior, Walter Benjamin argued that the ‘traces’ of the bourgeois interior, where the inhabitants have left their mark, are embodied by the inhabitants’ collection of objects, which they domesticised from the circulation of commodities as physical reminders of traditions, or Erfahrung (long experience), to preserve their privacy in the face of urbanisation.[54] In this context, the farmers’ gadget collection represents their resistance, rather than surrender, to modernity.

Bloch pinpointed the similarity between the peasantry and the urban bourgeoisie in their shared attachment to traditions despite their modern experiences. Considering the bourgeoisie in the Weimar context, he noted that the urban middle-class had been increasingly stripped of its capitalist privilege due to the economic crisis and because industry and the market economy only benefited large employers. Consequently, the ‘impoverished middle stratum seeks to return to the pre-war period when it was better off.’[55] As a result of their economic insecurity and nostalgia, they reverted to romantic beliefs such as ‘the attachment of the primitive man to the soil which contains the spirits of his ancestors’ and ‘the galvanic forces of German blood and the German meridian’.[56] Therefore, the peasantry and the urban bourgeoisie in Weimar Germany are comparable because they shared a socially and economically determined non-contemporaneity, namely their disillusion with the now and the tendency of looking back to older times. Just as Bloch astutely pointed out, it is this escapist nostalgia that eventually made them susceptible to the rhetoric of National Socialism, which emphasised[57] The Blochian concept of non-contemporaneity thus gives a nuanced account for the conservative stance of the peasantry and the middle class, attributing its reasons to their mode of production and economic insecurity, respectively.

Bloch’s explanation for the conservatism of the peasantry and the urban bourgeoisie and these social groups’ relationship with industrial capitalism challenges Scholz’s perception of provincial embourgeoisement that he conveyed in Industrial Farmers. Rather than on account of the two groups’ subjugation by industrial capitalism, as Scholz suggested in his work, the connection between the agricultural population and the urban middle-class rests on their mutual idolisation of the past.

AUGUST SANDER: AN ALTERNATIVE VIEW OF THE PEASANTRY

In part informed by the politicised cultural distinction between the city and the countryside as set out by the conservative revolutionaries, and in part assuming the dominance of industrial capitalism in the peasantry, Scholz demonised farmers as the ideological enemies of urban proletarians and left-wing revolutionaries. To an extent, Scholz’s debasement of peasants in Industrial Farmers is indicative of the urban left’s estrangement from the rural population, especially because Scholz’s work is one of the only examples of left-wing political art that depicts an agricultural subject.

Though communist and socialist theories have acknowledged the revolutionary potential of rural proletarians, and, as the hammer-and-sickle symbol signifies, envisioned farmers and urban workers standing in solidarity, the Weimar urban left rarely considered the rural population, the majority demographic within the German population at the time.[58] Tucholsky, for example, lamented in his essay, ‘when journalists in Berlin speak of Germany, they are fond of using the ready expression, “out there in the countryside”, which signifies a grotesque overestimation of the capital.’ Even when the left attempted to influence the countryside, they failed to understand the peasants’ needs and did so unsatisfactorily.[59] From Stapel’s perspective, the left forced their ideas on the countryside with ‘importunity and intellectual superiority’, resulting in a reactionary opposition from the country that made the peasantry susceptible to right-wing rhetoric.[60]

To an extent, Scholz’s choice of the subject of farmers as the vehicle for his critique of conservative ideologies, industrial capitalism, and the urban bourgeoisie in Industrial Farmers might be unfounded. Nevertheless, because of the work’s critical poignancy and appeal to the left-wing audience afforded by its rich cultural indexicality and politically nuanced medium, it contributed to the further estrangement of the peasantry by contemporary left-wing politics. Therefore, the analysis of Industrial Farmers alerts us to the ambiguity in the perceived provincial embourgeoisement and the seeming dissolution of the stereotypical city-country polarity that Scholz conveyed in his work. Cultural distinctions between the metropolis and the countryside dissipate because both the peasantry and the urban bourgeoisie were non-contemporaneous with modernity due to their respective mode of production and financial instability. However, this dichotomy remains due to the non-contemporaneity between the peasantry and the urban left, the latter of whom viewed the former from a perspective that prioritised the contemporary urban experience. Therefore, the demonisation of the peasantry in Industrial Farmers reinforced the asynchrony between the country and the city, which was then exploited by the political right.

In conclusion, I want to compare Scholz’s depiction of farmers to August Sander’s photography of a comparable social group. Despite the little attention paid to the peasantry in German art of the 1920s, Sander featured farmers in the Rhineland region extensively in his works. Photographs of farmers constitute the first of seven main sections of his portrait atlas, Citizens of the Twentieth Century, published posthumously.[61] In contrast to Scholz’s grotesque caricature of the peasant family, Sander’s photography creates a sense of objectivity, resulting from the perceived quality of its medium’s ability to authentically represent reality. However, as Andy Jones has pointed out, Sander’s photography is far from objective. Instead, it foregrounds ‘artisanal forms of knowledge’ originating from experience.[62] In contrast to Industrial Farmers, which shows farmers in a domestic interior, most of Sander’s portraits of the farming community, such as his 1912 portrait of a peasant family (Fig. 5), show sitters on the field or in front of the forest, emphasising their connection to the land. Also, Sander’s ‘germinal portfolio’, which includes twelve pictures of farmers, was intended to preface his other works as he believed farmers are archetypal and ‘the most basic building block of human society’.[63]

Though Sander’s emphasis on the peasantry’s instincts, rootedness, and primacy has invited readings of his works as reactionary and protofascist,[64] these images do not necessarily belie his conservative politics. Unlike Scholz, who subscribed to an understanding of farmers that prioritised the modern and the urban, Sander acknowledged and sympathised with farmers’ existence that is rooted in the past, a perspective resulting from his experience of spending years alongside the farming community. In fact, Sander’s grouping of his sitters according to their occupations, which recalls medieval guilds,[65] resonates with farmer’s classlessness according to Bloch, that ‘the peasantry feels itself to be […] still a “caste” which has remained relatively uniform’.[66] Jones has argued that ‘what Sander constructs in his image of the nation [based on guilds] is an imaginary resolution of the social crisis’ that the peasantry faced in Weimar Germany.[67] This crisis was the result of the peasantry’s classlessness amid dominant class-oriented politics and the contradiction between its ‘social conservatism’ and ‘resentful and vengeful political radicalism whose precise form was unpredictable.’[68]

It was the peasantry’s contradictory and unpredictable politics, Jones has further argued, that made them ‘open to be won by either Left or Right’.[69] In a sense, it was Sander, who claimed to not have any overt political agenda and only attempted to ‘honestly tell the truth about [his] age and people’, who grasped the essence of the peasantry’s existence,[70] of which the Weimar political left did not fully take advantage. It was the left’s underappreciation of the political potential of the countryside that resulted in the peasantry’s eventual shift to the right. Though most conservative revolutionary writers resisted Hitler, they unintentionally prepared the theoretical ground for National Socialism,[71] which readily won over the rural population. Bloch’s words are especially enlightening in this context, that the leftist revolution would remain futile ‘as long as [it] does not occupy and rename the living yesterday.’[72]

Acknowledgements

Sincerest thanks to Tom Wilkinson for his guidance and feedback throughout the drafting of this article.

Citations

- Huelsenbeck considered the Expressionists ‘men who never act’ and their abstract art ‘pathetic gestures which presuppose a comfortable life free from content or strife’. Richard Huelsenbeck, ‘First German Dada Manifesto (Collective Dada Manifesto)’, in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (eds), Art in Theory 1900-1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992), 253-255.

- Georg Simmel, ‘The Metropolis and Mental Life’, in Donald N. Levine (ed.), On Individuality and Social Forms(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971), 324-339.

- Simmel, 325.

- Martin Heidegger, ‘Creative Landscape: Why Do We Stay in the Provinces?’, in Anton Kaes et al. (eds), The Weimar Republic Sourcebook (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 426-428.

- An exception is Brigid Doherty, ‘Berlin’, in Leah Dickerman (ed.), Dada: Zurich, Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, New York, Paris [exhib. cat.] (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2005), 84-153. I will discuss her analysis of the work in due course.

- Karl-Ludwig Hofmann and Ursula Merkel (eds), Georg Scholz: Schriften, Briefe, Dokumente (Karlsruhe: Lindemanns Bibliothek, 2018), 13-19.

- See Richard Huelsenbeck and Raoul Hausmann, ‘What is Dadaism and What Does it Want in Germany?’, in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (eds), Art in Theory 1900-1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992), 256-257.

- Hofmann and Merkel, 19-20.

- Scholz also created a lithograph of this work a year prior to painting the subject, but the lithograph is not nearly as detailed as the 1920 work. See Michael Schwarz (ed.), Georg Scholz: Ein Beitrag Zur Diskussion Realistischer Kunst [exhib. cat.] (Karlsruhe: Badischer Kunstverein, 1975), 90.

- The modern flypaper depicted in the work was invented in 1909.

- Schwarz, 90.

- Schwarz, 90.

- Sonja Grunow, Kinderbild um 1900 (Münster: LIT Verlag, 2013), 197.

- ‘[…] schicke doch wieder Sachen zum ausstellen für Dada Show, biggest show on earth, schicke sofort Bauernbild – denn es ist wichtig – aber schnell Georg, schnell Georg, sonst hats keinen Zweck. Bierfrieden überall, Bierfrieden – mache das “Bauernbild” (Kosten werden bezahlt!!!!!!!!).’ Hofmann and Merkel, 105.

- [1] ‘Was den republikanischen Gedanken in jener abgeschwächten Form angeht, in der er bei uns hergestellt wird, so ist zu sagen, dass draußen im Lande nur fleckweise etwas von ihm zu merken ist […] Man muß so einen Bericht eines Diskussionsabends der Vereinigung der Republikanischen Presse lesen, um zu fühlen, wie geduldet sie noch alle sind.’ Kurt Tucholsky, ‘Berlin and the Provinces’, translated in Anton Kaes et al. (eds), The Weimar Republic Sourcebook (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1995), 418-420.

- Wilhelm Stapel, ‘The Intellectual and His People’, in Anton Kaes et al. (eds), The Weimar Republic Sourcebook (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1995), 423-425.

- Christian F. Otto, ‘Modern Environment and Historical Continuity: The Heimatschutz Discourse in Germany’, Art Journal, 43. 2 (1983), 148-157, doi: 10.2307/776650. [Last accessed: 1 November 2020]

- Otto has argued that works of other architects associated with Heimatschutz were either ‘imitative’, ‘vaguely vernacular’ or ‘larger and more expansive’. For him, Tessenow’s buildings are the embodiment of the new type of architecture that the Heimatschutz discourse advocated. See Otto, 154.

- Words are italicised in the original quotation. Michael Hays, ‘Tessenow’s Architecture as National Allegory: Critique of Capitalism or Protofascism?’ Assemblage, 8 (1989), 122, quoted in Stanford Anderson, ‘The Legacy of German Neoclassicism and Biedermeier: Behrens, Tessenow, Loos, and Mies’, Assemblage, 15 (1991), 63-87, doi: 10.2307/3171126. [Last accessed: 1 November 2020]

- Jeffrey Herf, Reactionary Modernism: Technology, Culture, and Politics in Weimar and the Third Reich (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 21.

- Herf, 26. This is an example of the conservative revolutionaries’ politicisation of Lebensphilosophie (philosophy of life), which has many resonances in German philosophy.

- Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West, trans. Charles F. Atkinson (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1950), vol. 2, 104, quoted in Bernd Widdig, Culture and Inflation in Weimar Germany (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 108-109.

- Herf, 55.

- Herf, 56; Widdig, 107.

- Raoul Hausmann, Am Anfang war Dada, ed. by Karl Riha and Günter Kämpf (Giessen: Anabas-Verlag Gunter Kampf, 1972), 49, quoted in Doherty, 90. Hausmann and Hannah Höch cited this type of photomontage as the inspiration for their ‘invention’ of the photomontage. For more on the origin of photomontage, see Doherty, 90-99.

- Doherty, 91.

- Michael White pointed out that though the term’s connotations has been mostly negative, it came to signify soldiers’ self-determination and perseverance. Michael White, Generation Dada: The Berlin Avant-Garde and the First World War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013), 299.

- Grunow, 197.

- George L. Mosse, The Image of Man: The Creation of Modern Masculinity (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 110.

- Mosse, 109-119.

- Grunow, 196-197.

- Matthew Biro, The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 173-174. Archangel Michael represents another link between religion and German nationalism. Since the nineteenth century, it had been the patron saint of the German military, celebrated by monuments such as the Völkerschlachtdenkmal (Monument to the battle of nations, 1913) in Leipzig. The German army’s last offensive on the western front in 1918 was also named ‘Operation Michael’. White, 298.

- Hofmann and Merkel, 38-46.

- Widdig, 40-41.

- Jürgen Koppatz, Geldscheine des Deutschen Reiches (Berlin: Verlag für Verkehrswesen, 1983).

- Biro, 172.

- John Bellamy Foster and Brett Clark, ‘Marx and Alienated Speciesism’, Monthly Review, 70, 7 (2018), https://monthlyreview.org/2018/12/01/marx-and-alienated-speciesism/. [Last accessed: 10 November 2020]

- Doherty, 93.

- Huelsenbeck, 253.

- Raoul Hausmann, ‘Synthetisches Cino der Malerei’, in Bilanz der Feierlichkeit: Texte bis 1933, ed. by Michael Erlhoff (Munich: edition text + kritik, 1982), vol. 1, 16, quoted in Doherty, 89. ‘The New Material in Painting’ was later published and exhibited with the title ‘Synthetic Cinema of Painting’ at the First International Dada Fair in 1920.

- Wolfgang Kayser, Das Groteske: Seine Gestaltung in Malerei und Dichtung (Oldenburg: Stalling, 1957), 136, quoted in Sabine T. Kriebel, Revolutionary Beauty: The Radical Photomontage of John Heartfield (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2014), 199.

- Kriebel, 199.

- Henri Bergson, ‘Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of Comic’, in Wylie Sypher et al. (eds), Comedy: An Essay on Comedy (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press), 105, 111, quoted in Kriebel, 175-176.

- Kriebel, 188.

- Brigid Doherty, ‘“See: We Are All Neurasthenics!” or, the Trauma of Dada Montage’, Critical Inquiry, 24, 1 (1997), 82-132, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1344160. [Last accessed: 1 November 2020]. It should be noted that some of Scholz’s Dadaist peers, such as Grosz and Otto Dix, were experimenting with the same fusion of medium at around the same time. For example, in 1922, the Malik Verlag published reproductions of Grosz’s works from 1919 in a booklet titled Mit Pinsel und Schere: Sieben Materialisationen (‘With Paintbrush and Scissors: Seven Materialisations’).

- Georg Lukács, ‘Zur Frage der Satire (1932), in Georg Lukács: Essays über Realismus (Neuwied, Luchterhand, 1971)’, vol. 4, 91-107, quoted in Kriebel, 182-183.

- Georg Himmelheber, Biedermeier 1815-1835: Architecture, Painting, Sculpture, Decorative Arts, Fashion, transl. John William Gabriel (Munich: Prestel, 1989), 9-11.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco and Sabine Grabner (eds), Is That Biedermeier? Amerling, Waldmüller, and More [exhib. cat.] (Vienna: Belvedere, 2016), 11-13.

- Sergiusz Michalski, New Objectivity: Painting, Graphic Art and Photography in Weimar Germany 1919-1933(Cologne: Benedikt Taschen, 1994), 99-100.

- Ernst Bloch, ‘Summary Transition: Non-Contemporaneity and Obligation to Its Dialectic’, in Neville Plaice and Stephen Plaice (transl.), Heritage of Our Times (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 97-148.

- Bloch, 99.

- Bloch, 100.

- Bloch, 101.

- Charles Rice, ‘Irrecoverable Inhabitations: Walter Benjamin and Histories of the Interior’, in The Emergence of the Interior: Architecture, Modernity, Domesticity (London: Routledge, 2007), 9-36.

- Bloch, 101.

- Bloch, 102.

- Bloch, 97.

- ‘Berlin and the Countryside’, in Anton Kaes et al. (eds), The Weimar Republic Sourcebook (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1995), 412. Despite Germany’s urbanisation from the late 19th century to the early 20th century, the population of Weimar Germany remained primarily rural. According to the 1925 census, only twenty-seven percent of the population lived in cities with more than 100,000 people, and twenty-seven percent lived in cities with a population from 5,000 to 100,000. Most notably, forty-six percent of the population still resided in small communities with less than 5,000 dwellers.

- ‘Wenn der berliner Leitartikler von Deutschland spricht, so gebraucht er gern den fertig genähten Ausdruck “draußen im Lande”, was eine groteske Überschätzung der Hauptstadt bedeutet.’ Tucholsky, 418.

- Stapel, 424.

- Ulrich Keller, August Sander: Citizens of the Twentieth Century, Portrait Photographs 1892-1952, ed. by Gunther Sander, transl. by Linda Keller (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986), 43.

- Andy Jones, ‘Reading August Sander’s Archive’, Oxford Art Journal, 23, 1 (2000), 1-21, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3600459. [18 February 2020]

- Keller, 43.

- See Jones, 4-5.

- Jones, 13.

- Bloch, 100.

- Jones, 19.

- David Blackbourn, ‘Between Resignation and Volatility: The German Petite Bourgeoisie in the Nineteenth Century’, in Geoffrey Crossick and Heinz-Gerhard Haupt (eds), Shopkeepers and Master Artisans in Nineteenth Century Europe (London: Methuen, 1986), 44, quoted in Jones, 16.

- Jones, 20.

- August Sander, ‘Remarks on my Exhibition at the Cologne Art Union (1927)’, transl. Joel Agee, in Cristopher Phillips (ed.), Photography in the Modern Era: European Documents and Critical Writings, 1913-1940 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989), 107, quoted in Jones, 3.

- Herf, 46.

- Bloch, 103.