Perseus and the Graiae was to be the pivotal scene of Edward Burne-Jones’s Perseus Series. As such, several versions created between 1875-1892 exist in the form of preparatory cartoons, a gilded low-relief oak panel (Burne-Jones’s original intention for the piece), and an oil-painted version created after the original oak panel was unfavourably received. The subject, in which the hero steals the only eye of the Graiae sisters, clearly references themes of sight and blindness. However, contrary to the tendency in previous scholarship to relate this to concepts such as wisdom and spiritual insight, this article proposes that a more literal reading of the body and the senses in relation to the Graiae sisters is appropriate. Furthermore, I suggest that the sensory body was a central line of enquiry in Burne-Jones’s artistic project. Drawing from the psycho-physiological writings of George Henry Lewes on muscular sensation and Walter Pater’s concept of the ‘Diaphaneitè’, I argue that Burne-Jones’s depiction of the sightless Graiae emphasises other, non-visual forms of sensation, especially touch. This draws the viewer’s attention to the Graiae’s heightened haptic sensitivity to their environment, offering us a glimpse of the process of detecting one’s surroundings without sight. Adolf von Hildebrand’s writings on ‘visual’ and ‘kinaesthetic’ looking provide a useful framework for elucidating and dissecting the different mechanisms of sight represented at work in the scene.

Introduction

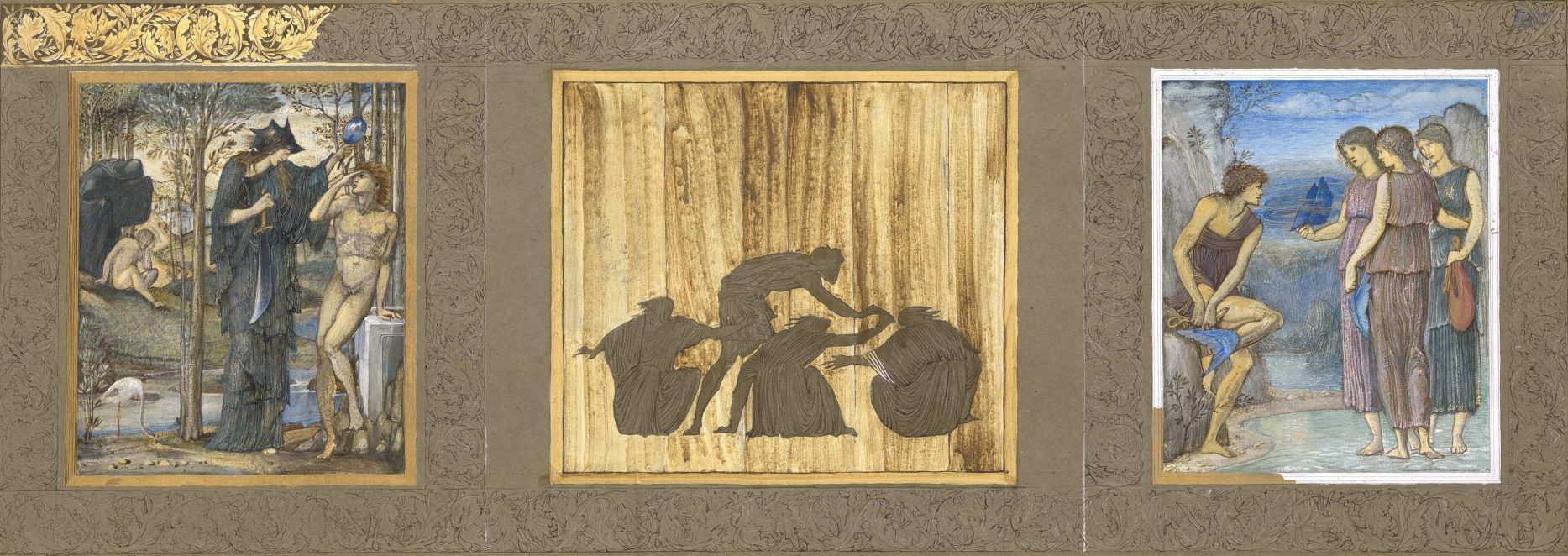

In 1875, Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) received a commission from the rising Tory politician Arthur Balfour to decorate the drawing room of his new house at 4 Carlton Gardens.[1] Balfour had recently encountered the work of Burne-Jones and, greatly impressed, gave the choice of subject for the new commission entirely to the artist.[2] Burne-Jones quickly produced designs for a sequence of ten panels to be placed around the room, set against decorative borders of William Morris’s Acanthus pattern (1875), which were to be realised in raised plasterwork (Fig. 1).[3] The four panels above the chimneypiece and doors were to be carried out in low relief using sculpted and gilded gesso.[4] However, Burne-Jones executed only one scene, Perseus and the Graiae, in this manner: after this work received an unhappy reception at the 1878 Grosvenor Gallery exhibition he abandoned the technique and made a new version of the scene in oil.[5]

The scene depicts the moment in Classical mythology when the hero Perseus renders the Graiae sisters blind by stealing their only eye, which they share by passing it around, in order to force them to give him the information needed for his quest. Elizabeth Prettejohn has noted that it is the only work in the Perseus Series that Burne-Jones refined through four successive versions: a small study (1875-76), a full-size gouache cartoon (1877-80) (Fig. 2), a gilded oak panel (1877-88) (Fig. 3), and an oil painting (1892) (Fig.5).[6] The special care paid to this particular work marks its importance in the series as a whole, and shows Burne-Jones’s evident interest in its major themes of vision and sight.[7] However, rather than exploring familiar territory, in which blindness and sight are read as raising issues of knowledge and wisdom, I propose a new reading, considering these themes in relation to the so-called muscular sense.[8] I approach this through the psycho-physiological writings on muscular sensation by George Henry Lewes (1817-1878), a friend of Burne-Jones’s, and through conceptualisations of sensitivity explored in the writings of Walter Pater (1839-1894). In each large version of Perseus and the Graiae, the haptic sensitivity of the Graiae is emphasised through Burne-Jones’s depiction of their garments as embodying fleshy, muscle-like organs that mediate between the figures and their environment. Through this, Burne-Jones reconceptualises the viewing experience of his works, eliciting the nonvisual mechanisms of negotiating between self and surroundings and giving spectators a glimpse into a world without sight. Burne-Jones, we will therefore see, used visual art in order to interrogate the limits of an ocularcentric conceptualisation of human existence, reminding us that being in the world involves the use, and awareness, of the whole body, not just the eyes.

In Interlacings (2008), Caroline Arscott investigates the bodily nature of Perseus’s armour throughout Burne-Jones’s series, exploring how the body appears to balance on the edge of vulnerability and protection, with skin-like metal seeming to disintegrate at the seams as though the hero is in the process of being flayed.[9] She also discusses the body of Andromeda as a counterpart to that of Perseus, represented in works such as The Doom Fulfilled (1888) as undulating and totally seamless.[10] The bodies of the blind Graiae, however, need further exploration. They too demonstrate vulnerability, although, unlike Perseus, this is due to their complete lack of armour or of any protective skin around their soft fleshy garments. Nevertheless, while they are composed of envelopes and flapping pockets of muscle-like draperies, they are depicted as decisively whole, supple and intact, and in no danger of flaking apart. Although the figures themselves seem intact, I argue that in this scene, Burne-Jones dissects and examines the senses, treating the group as one disassembled body, not quite working as one. The blinded Graiae reach out in search of their only eye, which has been captured by Perseus, whose flaking, skin-like armour is contrasted with the sisters’ elastic, muscle-like garments. This contrasts with Burne-Jones’s depiction of Perseus and the Sea Nymphs, where the unified group of fully assembled and fully alert female figures engage their faculties of touch, sight, and musculature as they look at Perseus.

This article commences by examining the striated, muscle-like forms in the initial full-size gouache cartoon Burne-Jones created in preparation for the gilded oak panel. I will discuss this in relation to Lewes’s conceptualisations of the muscular sense, to which he attributed the ability to detect ‘Effort, Resistance, Movement, Fatigue’.[11] Next, I will consider how the gesso panel depicts a heightened sensitivity, particularly in relation to Pater’s conception of the ‘Diaphaneitè’, an intensely pure and sensitive being.[12] Finally, I will examine the mechanisms of vision evoked in the oil reworking of the subject, drawing upon Adolf von Hildebrand’s (1847-1921) useful framework for understanding near and far looking in his Problem of Form in Painting and Sculpture (1893). By exploring these issues, I hope to redress an absence in current literature on Burne-Jones’s Perseus Series in relation to the themes of its pivotal scene, Perseus and the Graiae, as well demonstrate the benefits of looking further afield at broader cultural movements – such as nineteenth-century science – as tools for analysing nineteenth-century art.

Striae and String

There was a broad intellectual movement in the late nineteenth-century toward new ways of conceptualising the senses, body, and mind, with which Lewes was engaged.[13] Burne-Jones and his wife, Georgiana, were introduced to Lewes and his partner George Eliot in 1868, likely by the artist Frederic William Burton, and their friendship developed quickly.[14] A letter written by George Eliot describing a visit to Burne-Jones’s 1877 exhibition at the Grosvenor Gallery confirms their engagement with his work.[15] Burne-Jones was thus almost certainly aware of, and likely engaged with, Lewes’s thoughts on muscular sensitivity and the embodied mind, which Lewes first wrote about in 1859 in his The Physiology of Common Life. Lewes’s later publications on this subject, for example, his 1878 essay ‘Motor-Feelings and the Muscular Sense’, and his 1879 book Problems of Life and Mind, coincide precisely with the time Burne-Jones was painting his Perseus Series. An 1882 article in the Morning Post described the rendering of drapery in Burne-Jones’s Earth Mother (1882) and The Feast of Peleus (1872-1881) as ‘stringy clothing’ and ‘rope-like garments’.[16] The writer observed that the water poured by the figure in Earth Mother also ‘has the appearance of some blue fabric of the same kind as the clothing’, before continuing exasperatedly that, if there was any meaning to be gleaned from what he had described, it is the ‘kind which needs a good deal of “educating up” to, and life is too short for such a purpose.’[17] I, however, contend that these forms are a way in which Burne-Jones evokes the materiality and mechanisms of the sensory body, and of self-consciousness as outlined by Lewes.

The ‘stringy’ forms are found in each version of Burne-Jones’s Perseus and the Graiae but are particularly prominent in the gouache cartoon (Fig. 2), where continuous rows of rippling lines flow through cloth, landscape, and sky alike. The dense folds of fabric, intricately creased landscape, and streaked sky resemble striae in muscle. The condensed pleats of the garments, in particular, seem to show the direction of strain and movement like tendons. These muscle-like garments resemble externalised organs and evoke Lewes’s conception of the ‘muscular sense’, a form of spatial perception constituting part of his extended and embodied view of the ‘mind’. Furthermore, the fleshy, flabby amalgamation of drapery and landscape evokes nineteenth-century conceptions of the muscular sensations stretching out into the world and mediating between self and other bodies, forming the basis of general consciousness and a sense of self, as understood by Lewes. The visual similarity and continuity between the geological striation and the muscle-like garments also invoke new materialist studies, such as Jane Bennett’s book ‘Vital Matter’, in which she suggests that inanimate objects are also filled with agency and ‘thing power’.[18] Though the rocks do not have a sense of self, their muscle-like substance states them as another body exerting their own presence on the Graiae.

In ‘Motor-Feelings and the Muscular Sense’, written for the first issue of Brain (1878), Lewes claimed to be the first person to have suggested the hypothesis that muscles not only channel outgoing nerves, but also incoming sensations.[19] The striations of the fleshy garments could thus also be interpreted as nerves, carrying signals to and from the muscles. Lewes attributed the ability to sense exercise, weariness, and cramp to the muscles, and he argued that it is due to the sensitivity of the muscles that the body is able to make adjustments necessary for activities such as walking, dancing, and sitting upright.[20] Through a series of experiments involving removing the brains and skin of several frogs, Lewes was able to demonstrate that sensitivity resided in both skin and flayed muscle, though in different ways. He recorded:

I pinched the [skinned] limbs, pricked them, cut them, burnt them with acetic acid, and reduced them to cinders with the flame of a wax taper – and to all these violent stimuli the frog remained insensible, motionless, although a touch on the skin-patches made it hop or wince. […] Yet when it was placed on its back it immediately turned round again, and settled in a comfortable position.[21]

Through further experimentation he deduced that while the cutaneous sensibilities are able to detect surface texture and heat, the muscles are able to sense position, effort, and resistance, and therefore shapes and space.[22]

The blind sisters in Perseus and the Graiae, clad in their ‘stringy’ clothing, use these muscular sense organs to explore the shapes and space around them in order to construct a mental picture of their environment. Unlike Perseus, with his skin peeled back, as Arscott has discussed, the Graiae are depicted whole: inside out, rather than flayed. This is particularly evident in the sister on the far left, who appears to have her visible muscle riveted to her skin. At various junctures on her left arm, her chalky skin is visible beneath and between the fleshy pockets and begins to adopt the function of a skeletal structure. This suggests a different bodily configuration from that of dissection: here, muscle is also foregrounded, yet not entirely at the expense of skin. As Lewes asserted, the feeling of movement did not stem solely from the ‘foldings and stretchings of skin when the muscles contract’, but also from the sensations from the skin.[23] The Graiae are depicted whole, intact, but their muscles are brought forward and externalised, drawing attention to their increased reliance on their muscular senses as they attempt to reconstruct an image of the shapes and spaces around them without the use of the eye.

Here Steven Connor’s reassessment of the skin as a ‘background’ in The Book of Skin (2004) is useful: he writes of how the skin indicates ‘a ground, a setting, a frame’ for experience.[24] In Perseus and the Graiae, Burne-Jones’s concern is less with skin’s property as a mediating surface between body and individual external textures, and more with the muscles it contains, which mediate between self and broader resistances of substances and shapes. Like Connor, who sees skin as a setting for the interplay of other forces, Burne-Jones inverts the relationship between muscle and skin, depicting the skin as the literal ground upon which the muscles act. By using, and yet undermining, the visual language of foreground and background, Burne-Jones interrogates the limits of vision, and represents an invisible process and experience: the means by which something undetectable by the eye can be known. This is done by giving the viewer a glimpse of the blind sisters’ mental construction of space. To this end, Connor’s discussion of the ‘material imagination’ is also useful, and comes close to ideas expressed by Lewes. He argues that there is no way of imagining the material world that does not draw on or operate in terms of that material world, stating:

the merely visual or image-making faculty suggested by the word ‘imagination’ is always toned and textured by the other senses. Imagine a muddy field, or a clear sky. Is it possible not to imagine such things in a muscular fashion, in terms of the resistance or release that we would feel in encountering them[?] […] [T]he image in each case would be […] not only image but also usage. So the phrase ‘material imagination’ must signify the materiality of imagining as well as the imagination of the material.[25]

Through this ‘material imagination’, the Graiae sisters appear to try and organise what they feel into a mental image of their surrounding space. The striae-like flows resemble the contour lines of a map, lines which likewise link mental image and physical space, visualising the elevations and depressions of the outer limits of the landscape’s substance. As the Graiae feel different resistances with their muscles, they are able to map out the area in spatial terms while seeking their missing eye. After all, it is a physical connection to this object that will enable them to see.

As well as depicting the Graiae’s garments as externalised muscles and nerves, Burne-Jones describes the landscape with the same flowing striations, emphasising the sensitive muscly membrane extending into the world, mediating between self and other forms. Lewes wrote that the muscular sensations formed an important element of our general consciousness.[26] He stressed that the brain was not ‘the organ’, but rather ‘only one of the organs’ of the mind.[27] Instead of seeing the brain as the sole centre for sensation and thought, he viewed the mind ‘as much the sum total of the whole vital organism’.[28] He believed, therefore, that the muscular sense organs constituted part of the mind. By quoting an excerpt of Alfred Tennyson’s In Memoriam A. H. H. (1849) in The Physiology of Common Life, Lewes investigated the development of human consciousness through the sense of touch:

The baby new to earth and sky,

What time his tender palm is pressed

Against the circle of the breast,

Has never thought that ‘this is I’:

But as he grows, he gathers much

And learns the use of ‘I’ and ‘me,’

And finds ‘I am not what I see,

And other than the things I touch.’

So rounds he to a separate mind,

From whence clear memory may begin,

As through the frame that binds him in,

His isolation grows defined.[29]

The baby develops self-consciousness as he grows in awareness of his environment through the things he touches. Lewes drew from Thomas Brown’s Lectures on the Philosophy of the Human Mind (1822), in which Brown saw ‘feeling[s] of resistance’ as fundamental to knowledge of bodily reality and differentiating between self and other. According to Brown when we encounter a ‘feeling of resistance’ we are made aware of the existence of something external to ourselves.[30] Similarly, in Perseus and the Graiae, the sisters gain awareness of their relation to the surroundings through touch. As they feel around for their missing eye, it is not only a sense of space they begin to construct, but also a sense of self. Out of the swirling lines joining them to the ground like tendons and muscles, the Graiae’s hands and heads emerge. This suggests the interrelatedness of touch, symbolised by the hands, and of self, represented by their faces. Like the growing child’s ‘frame that binds him in’, the Graiae’s muscle-like garments are the agent in separating the self from their surrounding environment, mediating between them and the world.

While the continuous flows of nerves or striated muscles throughout garments and landscapes suggest that consciousness is founded on touch and muscular sensation, they also depict the world as an integrated and jostling vital mass. This was also, to an extent, the opinion of Lewes: he encouraged an embodied view of the mind, in which mind and matter are not distinct, but rather one continuous entity.[31] In Burne-Jones’s cartoon, we can detect this conception of the mind, body, and world being integrated and in a constant state of flux through the shifting and metamorphosing of skin, flesh, armour, and draperies, which give the impression of multiple actions and sensations happening at once. The fabric over the far-left sister’s breast seems to vanish or metamorphose into skin. This is similar to the armour at the top of Perseus’s thigh and buttock, which seems either to become transparent or to turn into skin. Like a cross-sectional diagram, this depiction gives a sense of several processes operating simultaneously. Muscle and skin simultaneously feel the resistances of other substances and surfaces. Ideas of shapes and space are formed at the same time as ideas of texture. These concurrent sensations and images mirror Lewes’s concept of the synchronous activities of the senses both forming and instructing the mind. This shifting of substance and the flowing forms of the figures, landscape, and sky offer a sense of constant flux and togetherness operating between body and mind, self and world.

Gesso and Gold: Fine Edges of Light

At the time Burne-Jones first exhibited his versions of Perseus and the Graiae, the sensory body was being extensively discussed in science, literature and art.[32] There was concern, particularly among figures involved in the Aesthetic Movement, about a general distancing occurring between people and the natural world, resulting in a demise of appreciation and sensitivity towards the material environment.[33] In a letter from Burne-Jones’s close friend William Morris to his wife in 1870, Morris described modern society as enveloped in a ‘crust of dullness and ignorance’.[34] This detachment is here conceived not merely as distancing, but as a physical and bodily ‘crust’ like a hardened skin or accumulated and congealed dead residue. Mind and matter are again described as inextricably linked. A passage in George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1871) also suggests a concern about existing in a ‘wadded’ state:

If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence. As it is the quickest of us walk about well wadded with stupidity.[35]

Arscott identifies the male subject of Burne-Jones’s works as ‘scarcely wadded, or utterly unwadded, so that sensibility is not blunted. Aesthetic experience is thereby enhanced.’[36] I agree with Arscott that Perseus’s senses are not ‘blunted’ by his armour. But what of the Graiae sisters? My reassessment of Perseus and the Graiae in relation to nineteenth-century ideas surrounding the muscular sense will show that the Graiae sisters are depicted not only as ‘unwadded’ or ‘crust-less’ but very much as physically inverted.

The writer and critic Walter Pater was a leading figure of Aestheticism, a late nineteenth-century artistic movement in which Burne-Jones was involved, which focused on representing the activation of the senses and imagination over moralistic or socio-political themes.[37] Pater was preoccupied with the body’s sensitivity to the energetic flow and flux of the material world. This preoccupation was characteristic of contemporary theories of vitalism, spearheaded at the time by Johannes Müller’s Elements of Physiology (published in English in London by 1843), which contended that the behaviour of light and sound waves showed that all living organisms were animated by some non-physical element.[38] In his famous ‘Conclusion’ to The Renaissance (1868), Pater wrote:

Our physical life is a perpetual motion of them – the passage of the blood, the waste and repairing of the lenses of the eye, the modification of the tissues of the brain under every ray of light and sound […]. Like the elements of which we are composed, the action of these forces extends beyond us […]. Far out on every side of us those elements are broadcast, driven in many currents.[39]

As in Burne-Jones’s cartoon, where ‘nerves’ run out through the muscular forms of the Graiae’s clothing into their surroundings, for Pater, the human being was a porous entity, moving through and yet deeply connected materially and energetically to the world. The gilded oak panel of Perseus and the Graiae (Fig. 3) evokes Pater’s ideas in his essay ‘Diaphaneitè’ (1864), in which he described an idealised and extremely sensitive being. Pater wrote of this character that

i[t] does not take the eye by breadth of colour; rather it is that fine edge of light, where the elements of our moral nature refine themselves to the burning point. […] The world has no sense fine enough for those evanescent shades.[40]

Pater described this type of character as rare and most precious. Anne Varty explains how the grave accent suggests that ‘Diaphaneitè’ is a Greek word, not a French one, thus assuming the second-person plural imperative verb ‘[you shall] become transparent!’ or ‘[s]hine through!’, reinforcing the sense that this work is a manifesto.[41] The Diaphaneitè, hyper-sensitive but completely pure, calls to mind the bodies in Burne-Jones’s gilded gesso version of Perseus and the Graiae. Here the evocation of striated muscle is more evident: the low relief drapery is painted with rose pink and the streaks of gold cause it to glisten like fresh meat. By emphasising the visual sensitivity of these lines, Burne-Jones visually brings the muscular and tactile senses of the figures beyond Pater’s ‘breadth of colour’ to a shining ‘fine edge of light’, which is intensified as the blind Graiae come to depend more and more on their non-visual senses.

An illustration depicting the nervous system in Lewes’s Physiology of Common Life shows a strong resemblance to Burne-Jones’s ‘stringy clothing’, alluding to the sensitivity suggested by these externalised muscular forms (Fig. 4). Unlike illustrations in the book that depict dissected animals and body parts through black lines on white ground, this drawing depicts the living human in block black ink, with the subject of the diagram, the nervous system, depicted in negative form as blank white page. These glowing nerves suggest a metaphorical link between sight and touch: while other areas of the body are left in obscurity, the nervous system is the ‘light’ in the darkness, making that with which it comes into contact more comprehensible. Furthermore, that the nerves are represented as an absence of ink (and thus composed of the same material as the rest of the page surrounding the body) makes literal the flow from external sensory stimuli into the human sensorium, described by Pater in his characterisation of the body as a porous entity subject to the flow and flux of the material world. There is a strong resemblance between the glowing nerves in this diagram and Burne-Jones’s low relief panel where the gilded folds in fabric reflect the light and shine bright white, emphasising the muscular sensitivity of the wearers.

In Burne-Jones’s panel, although the muscular sense is visually intensified through the incised ‘fine edge[s] of light’, cut through the raised gesso and gilded, it is the stolen eye that is depicted as the ultimate product of this refinement. The eye is the ‘burning point’ of the composition, accentuated by the gold rays that emanate from the sharply raised metal dome and by a glow, perhaps created by rubbing chalk into the grain of the wood. Were the Graiae to have their eye, they would be able to apprehend and ‘feel’ in a single glance the landscape which here they begin to map out and slowly comprehend through touch. This singular organ, like the Diaphaneitè, offers a touch so sensitive it needs no contact.

The white chalk picking out the wood grain invites a comparison between the superimposed golden rays radiating from the eye and the physical, interconnected vital system of the wood’s fleshy substance, and alludes to the two systems of spatial comprehension: sight and touch. The veins of sap visible in the unprimed wood evoke human musculature and its nervous apparatus, and provide the conceptual framework for the image, suggesting the means and matter by which the Graiae sisters are attempting to visualise their environment. Despite the rocky landscape being almost entirely omitted in this version of Perseus and the Graiae, the shape of the land is suggested by the slumped forms of the hanging drapery. However, it is only these points of resistance – where the bodies and drapery are pressed against the boundaries of the landscape – that are rendered visible. The more subtle intricacies of these surfaces are only visible at points of contact between skin and ground, where the terrain is hinted at through lines that quickly fade out into the woodgrain. This renders viewers similarly blind to visual stimuli beyond that which the figures can know through touch. The processes employed by the Graiae to discern their surroundings are made visible, and we are shown how the synchronous activities of detecting shape and space through the muscular sense occur as the skin senses textures and details of individual surfaces. Thus, not only does Burne-Jones depict the Graiae’s bodies as locations of heightened sensitivity, representative of the muscle sense brought to the surface, but he also enables the viewer to see this process. We are helped to visualise their world as they do: a world without sight, understood as shape, substance, and texture, appreciated through the haptic and muscular senses, heightened and ‘burning’ gold due to our ‘blindness’, which mirrors theirs.

To complete the panel, Burne-Jones sought the help of gesso specialist Osmund Weeks. For the clothing of the figures, a layer of gesso was applied, and, once bone-dry, it was carved and incised to create form and detail. The carved gesso was then painted, gilded, and silvered. The letters for the Latin text were carved in mahogany, then gessoed and gilded before being pinned to the oak panel individually.[42] The figures’ heads, hands, and feet were executed in oil, though in thin enough layers that in places the grain of the oak panel remains visible. Arscott writes that ‘the composite nature of the [Perseus] reliefs might conform to th[e] logic of a reassembled body’, and explores how even Burne-Jones’s paintings were manipulated and built up using consecutive layers of distinct elements.[43] Fleshy gesso was layered onto the wooden support like muscle onto the skeleton, and then covered with a skin of paint, gold, and silver. Burne-Jones also described the construction of his paintings in terms of anatomical reconstruction:

It won’t do to begin painting heads or much detail in this picture till it’s all settled. I do so believe in getting in the bones of the picture properly first, then putting on the flesh and afterwards the skin, and then another skin; last of all combing its hair and sending it forth to the world. If you begin with the flesh and the skin and trust to getting the bones right afterwards, it’s such a very slippery process.[44]

This suggests that both the depicted image and the material substance and structure of the painting were essential to Burne-Jones. Though Arscott explores the bodily aspect of the work of art as a fabrication of composite parts, she does not explore the idea of the work itself as a sensitive entity.[45] I propose that the gilded surface of the Graiae’s chitons can be understood as nerves burning at the encounter of sensory stimuli. Whether the gilding and silvering is taken as an intensely sensitive skin, or as the burning sensations of the muscles, is perhaps of little consequence: as Lewes, in ‘Motor-Feelings and the Muscular Sense’, maintained, the nerves, muscles and skin are all indispensable to muscular sensation.[46] Indeed, the panel’s capacity to reflect light mimics the sensitivity of the Diaphaneitè to the world: reflected light shines brightly from the gilded lines, changing with every moment as the sun follows its course throughout the day, and with every movement of the viewer as they lean forward to take a closer look. Just as the panel embodies the Diaphaneitè through its sensitivity to light, the viewing experience also places the viewer in the position of the Diaphaneitè, where they become equally sensitive to the light changing in relation to their position to the work.

Furthermore, through the materiality and three-dimensionality of the work, with its incised lines and sculptural gesso work, Burne-Jones creates a viewing experience that evokes the haptic processes of comprehending the world without sight. In the gesso version of Perseus and the Graiae, the immediate material presence of the work is exemplified by the unashamedly naked oak panel. This caused much confusion when it was exhibited: it was a more tactile and crude sight than was familiar at the Grosvenor Gallery, used to works offering illusion, not the raw material of the constructed object. Visitors to the gallery in 1878 were perplexed by the manner of its execution. The critic for the Essex Standard wrote: ‘[I]t seems a pity that the figures, which are well outlined, should be spoiled by such an extraordinary manner of representation.’[47] The artist Graham Robertson described the panel as ‘a rather unsuccessful experiment in combining oil-painting with thin sheets of metal nailed on to the panel.’[48] These remarks demonstrate that Burne-Jones was experimenting here with something entirely new to the Victorian art world, surprising even for the newly opened and avant-garde Grosvenor Gallery. Somewhere between two-dimensional painting and three-dimensional sculpture, the gessoed panel refused to be easily categorised.

Burne-Jones further complicated the expected visual language of the piece through his monumental inclusion of raised and gilded text, to which he allotted the entire top half of the composition. As the intended centrepiece of Balfour’s drawing room at 4 Carlton Gardens, the panel carried an inscription explaining the mythology of the series.[49] Instead of choosing lines from Morris’s Chaucerian English version of the poem, Burne-Jones used a Latin text prepared for him by the classical scholar Richard Jebb. The choice was statelier in diction than Morris’s version due to its use of dactylic hexameters, the metre of ancient epic poetry.[50] In literal translation it reads:

Pallas urges on Perseus by her advice. She equips him with arms. / The Graiae, deprived of eyesight, show him the secret dwelling / Of the Nymphs. From here, his feet winged, his head hidden in shadow, / The Gorgon, alone mortal out of these non-mortals, / He strikes with his blade. The twin sisters rise, and press on him. / Behold Atlas stony, and, snatched from the slain dragon, / Andromeda, and the comrades of Phineus now stony bodies. / Behold the maiden wondering in a mirror at terrible Medusa.[51]

Burne-Jones further complicates an easy reading of this text for his audience at the Grosvenor Gallery by giving it the visual form of ancient inscriptions, with Roman majuscule lettering and dots to separate the words.[52] Though the text is rendered obscure to many through its use of Latin and its ancient script, it is made more haptically apprehensible by being raised above the surface of the work, like braille. Although viewers would not have been physically able to touch the words, their raised surfaces evoke the sensation of touch: they exist in three, not two dimensions. Furthermore, it could be argued that the process of reading is more akin to feeling than seeing, as each component of the text must be individually ‘felt’ and pieced together in order to construct an idea of its meaning, as opposed to comprehending a scene at a glance. It also employs mental image-making facilities to visualise the narrative, compiled of several fragmented moments. Burne-Jones thus offers the viewer a glimpse into the process by which the blind sisters perceive the world around them by making viewer’s ocular experience evoke a haptic one.

In ‘Frederic Leighton’s Athlete Wrestling with a Python and the Theory of the Sculptural Encounter’ (2004), David Getsy discusses the way in which viewers might remember looking at a sculpture.[53] He investigates the definition of the ‘imago’ used by Jean Laplanche and Jean-Bertrand Pontalis to describe the fragmented amalgamation of experiences woven together during a sculptural encounter.[54] Laplanche and Pontalis wrote that the imago ‘should be looked upon, however, as an acquired imaginary set rather than as an image […]. Feelings and behaviour, for example, are as just as likely to be the concrete expressions of the imago as are mental images.’[55] For them, the recollection of a sculpture was dependent on a series of experiences, visions, angles, and other associations. Getsy describes the ‘productive energy of these various forces’ as giving the ‘internal psychic representations of individuals and experiences such potency and variability.’[56] Through remembering a sculptural encounter with Burne-Jones’s gesso version of Perseus and the Graiae, the viewer might remember a glistening, fragmented, and moving view of several angles and details. We could compare this memory to the mental image supposedly amassed by the Graiae of their environment and own bodies, through the piecing together of several haptic sensations. Furthermore, the ‘imago’ is deeply sensitive, being different for each viewer, again evoking the ideas of Pater and the heightened sensitivity to which he thinks one should aspire. Getsy finishes his chapter:

The viewer’s potential for corporeal engagement became a persistent issue for sculptors and critics, who began to understand the relations between viewer and object to be not static and distanced but potentially intimate, physical, and bodily.[57]

Burne-Jones’s Perseus and the Graiae demands this active bodily engagement through its highly reflective sculptural elements. The panel, though presented as a visual object, exhibits this potential for an ‘intimate, physical, and bodily’ engagement with the work. Furthermore, since the work is also a sculptural object, engagement with it becomes necessarily physical and bodily through the construction of an ‘imago’. This happens through a unique series of spatial and temporal experiences that occur through the act of looking, and in turn reflect the abstracted and fragmented ‘view’ of the Graiae in their sightless world.

A Vision Dissected

It is significant that it was Burne-Jones’s original intention to display the Graiae raised and gilded, feeling around for their eye on a plain oak panel. However, it is also revealing to examine the alterations he implemented in translating the piece into something more illusionistic, seemingly preferred by his Victorian audience (Fig. 5). During this transformation, he preserved the evocations of those processes of comprehending the world without sight, albeit articulated more symbolically. I will argue that by replacing the text with a screen-like depiction of the misty, mountainous background, Burne-Jones depicts a conceptualisation of distance as flattened through sight. Additionally, by painting the terrain under the Graiae as solid and defined, he depicts closeness as understood three-dimensionally through touch. Adolf von Hildebrand’s Problem of Form in Painting and Sculpture is especially useful for exploring these ideas. Though first published in German in 1893 and translated into English in 1907 after the completion of all of Burne-Jones’s versions of Perseus and the Graiae, Hildebrand’s text provides a useful framework for considering the different ways in which the figures in the scene demonstrate the sensing of space.

Aesthetic experiments across Europe at the end of the nineteenth century helped to prepare the ground for the theoretical issues that Hildebrand explored. Notable among these experiments were works that, like those of Burne-Jones, investigated the relationship between sight, perception, bodies, and sensation. In his book, Hildebrand compared the different optical effects of viewing an object at a close distance with those of viewing it from far away. The terms he gave these different ways of looking were the ‘visual’ and the ‘kinaesthetic’.[58] Whereas a distant object appears flat and the whole can be perceived in one look, a closer object is seen through a compilation of glances, since

the whole object can no longer be seen at a glance. Instead of one complete picture, [the spectator] now has several which [they connect] together by a swift succession of eye movements.[59]

This fragmented series of abstracted images is compiled in the mind to create an idea of the object as a whole. Though Hildebrand specifically addresses eyesight, I argue that his model of close-up, ‘kinaesthetic’ looking and distant, ‘visual’ looking is articulated in Burne-Jones’s oil version of Perseus and the Graiae through registers of touch. Here, the Graiae interpret their immediate surroundings ‘kinaesthetically’, by piecing together an abstracted mental image of their environment through a fragmented series of haptic sensations, whereas their desired mode, the more immediate one of further-reaching sight, is captured by Perseus with a single touch.

There are two different eyes that mark a compositional divide through the middle of Burne-Jones’s Perseus and the Graiae. The first is that which Perseus holds between his thumb and index finger. Unlike the earlier gesso version in which the eye is accentuated, gilded, shining, and sharply raised from the flat support and Perseus’s painted fingers, the eye in the oil version is barely visible, darkened by the shadow of the hero’s hand, alluding perhaps to how his possession thereof darkens the Graiae’s vision and renders it useless. The second eye, I contend, is visually suggested by the middle Graia’s turned head, which forms the pupil, and her outstretched arm as well as that of Perseus, which together form the upper and lower eyelids. However, the hands of Perseus and the central Graia that define the corners of this eye do not quite meet. This, as I will now show, demonstrates how Burne-Jones dissects the contrasting registers of vision and spatial comprehension at play in the work. Perseus’s register of vision is visually constituted by two key elements: his flaking, skin-like armour, which draws our attention to surface, and his possession of the eye, symbolising sight. The second register, that of the Graiae, is constituted by their soft, muscle-like garments, which allude to a sensing of substance and shape rather than surface texture, and their open and reaching hands, drawing attention to their blind dependence on touch.

This contrast is also demonstrated through the picture’s overall composition, which is likewise divided in two. Perseus, aligned with eyesight, occupies the top half of the painting and is juxtaposed against a backdrop of distant hills, while the Graiae, aligned with the tactile senses, occupy the lower half and are depicted as firmly planted in the terrain on which they crouch. This distinction both accentuates the figures’ respective forms of vision and characterises the entire scene: the senses are dissected and the different mechanisms of sight examined. In the upper half of the painting, Perseus’s rounded back rises up from among the figures in the foreground like the rolling hills in the distance, linking his privilege of sight to the raised land and far-reaching views available of (and, presumably, from) the peaks. The smoky atmosphere depicted in the upper half of the painting further alludes to the expanse discernible through sight. The mist, which fills the air between Perseus and each peak and dell, makes visible the operation of vision itself, inhabiting the space between substances which ends at their surfaces. Curiously, though, despite the suggestion of distance, the rendering of the mountains appears extremely flat, as though a screen has been pulled down behind the group. Perseus, now with three eyes, is held by a bulging, muscly pocket created by the Graiae’s outstretched arms and hanging garments. Slotted just behind these fleshy folds, he is kept in an envelope on the picture’s surface. Reaching across the sisters, parallel to the picture plane, he is compressed against the canvas, his flattened and far-reaching body paralleling his vision, which enables him to comprehend the entire scene in a single glance.

Burne-Jones contrasts distant viewing, which Hildebrand characterises as a two-dimensional image, with the three-dimensionality of experiencing a close object through ‘kinaesthetic’ looking. This is demonstrated in this painting through the Graiae’s muscular and tactile senses. The flatness of Perseus’s position in the composition contrasts with the outstretched, foreshortened hand of the left Graia who reaches out into the space between viewer and painted canvas. She leans away from Perseus, her knees and shoulders pushing out from the plane he inhabits. Her arms and torso create x, y, and z axes, demonstrating the three dimensions she attempts to map, using herself as the reference point. Although she reaches outwards, she and her sisters are depicted as fused to the terrain. The outstretched arms of the Graiae, as they feel around for their missing eye and their garments, accentuate the horizontal forms of the uneven ground beneath them. The steel grey colouration used throughout the drapery and landscape further relate the Graiae to the terrain, blurring the boundaries between folds of fabric and the sweeping curves and loops of the rocky, though fleshy-textured, land. The smooth shading describing soft curves juxtaposed against deep, dark crevices and holes in the ground appears as bodily dips and hollows: rolls of fat, orifices, and creases in skin. This embedding of the Graiae in their immediate surroundings adds to the sense that they can only visualise that which they touch. In contrast to the misty mountain, the foreground is depicted in clearer and much more substantial terms. This corresponds to the tangibility of things sensed through touch, whereas things sensed through ocular vision are distant and can be illusionistic, like a painted screen, evoked by the depiction of the mountains, or, even, the oil-painted version of the Perseus and the Graiae in its entirety.

Conclusion

In all three versions of Perseus and the Graiae, although the living, sensitive body is evoked, it does not quite function as a unified whole, and everything is held in suspense: senses and organs alike are disassembled and examined. In the final, oil version of the work, the differing mechanisms of understanding the environment are depicted as operational but separate: ‘visual’ looking is separated from ‘kinaesthetic’ looking. The eye is kept from the Graiae, and Perseus tiptoes through the scene delicately holding it as though trying to avoid contact as much as possible. Skin and sight, embodied by Perseus, are stripped off and pinned above the bare muscle of the Graiae. Their lack of contact is further emphasised through Burne-Jones’s orchestration of each instance of skin which fails to make contact with another piece of skin, sometimes narrowly. In this way, the Graiae teeter on the edge of feeling and feeling nothing. Perhaps the expectation of touch increases their sensitivity even more, as they attempt to map out the landscape and create a spatial image of their surroundings in their search for the missing eye, a further-reaching sensory organ. As the bodies of the sisters are turned inside out, so too is our vision of them, because the blind imagination is, to an extent, rendered visible.

In his version of the tale of Perseus and the Graiae, thus, Burne-Jones presents us with a physical inversion and dissection of the body and its senses, drawing our attention to the sensory body and the materiality of self-consciousness – as conceptualised by Lewes – and the relationship between sight and touch. Like the bodies within them, this set of paintings does not function as a unified whole, but each version tells us something about Burne-Jones’s approach to the subject matter. The disproportionate reliance of each figure on their dominant sensory organs (for Perseus, his eyes, and for the Graiae, their muscles) heightens their individual sensitivity. Our awareness of our own senses and bodies in relation to the work is thus also emphasised as we view the figures and their methods of comprehending the world. Burne-Jones’s interpretation of the myth underscores the sensory elements present in the tale itself and makes these visible to a viewer, thus presenting new possibilities for artworks to draw upon, and reference, multiple senses. His visual interpretation of the myth serves another purpose, too: it calls for the individual to be not only unwadded, but fully connected to their surroundings.

Ruth Helen Smith completed her MA and BA at The Courtauld Institute of Art, graduating with distinction in 2016 from Professor Lucetta Johnson’s MA course ‘Flesh and Fabric: The Victorian and Edwardian Interior’. Ruth then undertook a two-year diploma in figurative painting at The Heatherley School of Fine Art and is now working as an artist and as curator at Worlds End Studios, Chelsea. Currently artist in residence at Battersea Power Station Phase 3 and at Husk, Limehouse, Ruth’s practice and art historical studies centre on construction and interconnectivity, particularly with regards to nineteenth-century and contemporary London and the self.

Citations

[1] Stephen Wildman and John Christian, Edward Burne-Jones, Victorian Artist-Dreamer [exhib. cat.] (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998), 221.

[2] Arthur James, 1st Earl of Balfour, Chapters of Autobiography, ed. by Blanche Elizabeth Campbell Balfour Dugdale (London: Cassell and Co., 1930), 233.

[3] Caroline Arscott, William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones: Interlacings (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008), 57.

[4] Wildman and Christian, 221-222.

[5] For example: ‘Literary Notices’, Essex Standard, West Suffolk Gazette, and Eastern Counties’ Advertiser, 2450, (21 June 1878), 6; and W. G. Robertson, Letters from Graham Robertson, ed. by K. Preston (London: H. Hamilton, 1953), 420.

[6] Elizabeth Prettejohn, ‘The Series Paintings’, in Alison Smith (ed.), Edward Burne-Jones [exhib. cat.] (London: Tate Publishing, 2018), 184.

[7] Prettejohn, 184.

[8] For traditional readings on blindness and sight as related to wisdom and knowledge, see Kate Flint, ‘Blindness and Insight’ in The Victorians and the Visual Imagination (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 64-92; for a reading of blindness and sight in relation to Perseus and the Graiae, see Prettejohn, 184.

[9] Arscott, 71.

[10] Arscott, 73.

[11] George Henry Lewes, The Physiology of Common Life (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1860), vol. 2, 280; and George Henry Lewes, ‘Motor-Feelings and the Muscular Sense’, Brain: A Journal of Neurology, 1.1 (1 April 1878), [14-28], 27.

[12] Walter Pater, ‘Diaphaneitè’ [July 1864], in Charles Lancelot Shadwell (ed.), Miscellaneous Studies: A Series of Essays by Walter Pater (New York and London: Macmillan and Co., 1896), 216.

[13] For example: Thomas Kingsmill Abbott, Sight and Touch: An Attempt to Disprove the Received (or Berkeleian) Theory of Vision (London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green, 1864); Alexander Bain, The Senses and the Intellect (London: John W. Parker and Son, 1855); Charlton Bastian, ‘On the Muscular Sense and on the Physiology of Thinking’, British Medical Journal, vol. 1, 435, (1 May 1869), 394-396; Stanley Hall, ‘The Muscular Perception of Space’, Mind 3 (1878), 433-450.

[14] Hugh Witemeyer, George Eliot and the Visual Arts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/eliot/hw/2.1.html. [Last accessed: 27 July 2019].

[15] George Eliot, The George Eliot Letters, ed. by Gordon Sherman Haight (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1956), vol. 6, 365.

[16] ‘The Grosvenor Gallery’, Morning Post, 34275 (2 May 1882), 5.

[17] Morning Post, 5.

[18] Jane Bennett, Vital Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010), 2.

[19] Lewes (1878), 19.

[20] Lewes (1860), 280; and Lewes (1878), 27.

[21] Lewes (1860), 183-184.

[22] Lewes (1860), 183-184; and Lewes (1878), 15.

[23] Lewes (1860), 282.

[24] Steven Connor, The Book of Skin (London: Reaktion Books, 2004), 37-38.

[25] Connor, 40-41.

[26] Lewes (1860), 286.

[27] Lewes (1860), 4-7.

[28] Lewes (1860), 344.

[29] Alfred Tennyson, In Memoriam A. H. H. [1849], (London and New York: The Bankside Press, 1890), canto 45, 51-52. Quoted in Lewes (1860), 294.

[30] Thomas Brown, Lectures on the Philosophy of the Human Mind (Andover: Mark Newman, 1822), vol. 1, 460-461, 509, 462.

[31] George Henry Lewes, Problems of Life and Mind (London: Trübner & Co., 1879), vol. 2, ser. 3, 149.

[32] For example: Abbott (1864); Bain (1855); Bastian, 394-396; and Hall, 433-450.

[33] Allan R. Ruff, ‘Ruskin, Morris and the Garden City’, Arcadian Visions: Pastoral Influences on Poetry, Painting and the Design of the Landscape (Oxbow Books, 2015), 163-180.

[34] Letter from William Morris to Jane Morris, 3 December 1870, in Norman Kelvin (ed.), The Collected Letters of William Morris (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), vol. 1, 128.

[35] George Eliot, Middlemarch (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1871), vol. 1, 351.

[36] Arscott, 24.

[37] Arscott, 11.

[38] Johannes Müller, Elements of Physiology, transl. by William Baly (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1843); Laura Otis, ‘Johannes Müller’, The Virtual Laboratory (Published: October 2004, Last accessed 29 July 2019, http://vlp.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/essays/data/enc22?p=6).

[39] Walter Pater, ‘Conclusion’ [1868] The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry (London: Macmillan and Co., 1912), 233-234.

[40] Pater (1864), 215-216.

[41] Anne Varty, ‘The Crystal Man: A Study of the “Diaphaneitè”’, in L. Brake Jagger and I. Small Hlavenkova (eds), Pater in the 1990s (Greensboro: ELT Press, 1991), 258.

[42] ‘Interactive Perseus’, Museum Wales, (Published: n.d., Last accessed 12 February 2016, http://www.museumwales.ac.uk/rhagor/interactive/perseus/).

[43] Arscott, 81-82.

[44] Georgiana Burne-Jones, Memorials (London and New York: The Macmillan Company, 1904), vol. 2, 322-323.

[45] Arscott, 78.

[46] Lewes (1878), 16.

[47] ‘Literary Notices’, The Essex Standard, West Suffolk Gazette, and Eastern Counties’ Advertiser, 2450 (Friday 21 June 1878), 6.

[48] Walford Graham Robertson, Letters from Graham Robertson, ed. by Kerrison Preston (London: H. Hamilton, 1953), 420.

[49] Wildman and Christian, 223.

[50] Prettejohn, 183.

[51] Translation by Charles Martindale in Prettejohn, 184. For another translation and discussion on the text, see Anne Anderson and Michael Cassin, The Perseus Series – Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones [exhib. cat.] (Southampton: Southampton City Art Gallery, 1998), 22.

[52] Prettejohn, 183.

[53] David Getsy, ‘Frederic Leighton’s “Athlete Wrestling with a Python” and the Theory of the Sculptural Encounter’, Body Doubles: Sculpture in Britain 1877-1905 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004), 36-42.

[54] Getsy, 38.

[55] Jean Laplanche and Jean-Bertrand Pontalis, Language of Psychoanalysis, trans. by Donald Nicholson-Smith (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1973), 211.

[56] Getsy, 37.

[57] Getsy, 42.

[58] Adolf von Hildebrand, The Problem of Form in Painting and Sculpture, transl. by Max Friedrich Mayer and Robert Morris Ogden (New York and London: G. E. Stechert and Co., 1907), 21.

[59] Hildebrand, 22.