Before the popularisation of printing, and indeed even afterwards, books of hours were marked by diversity, differing from region to region and book to book. Rather than calling the book of hours the manuscript equivalent of a ‘best-seller’ in the late medieval period, it might be more accurate to call it a best-selling genre, and one that encompassed much variety.[1] The making of a single, personal book of hours necessitated a great many decisions as to design, text and decoration, all filtered through concerns of doctrine and cost. Each book of hours, then, presents a modern viewer with a complex visual language ranging far beyond the chosen prayers and readings. The texts and images of a single prayer book interacted in ways that produced a layering of meaning within its pages. The book of hours has been cited as evidence of a growing trend towards individualism and interiority in the fourteenth century among the laity, but the Office of the Virgin is also heavily tied into concepts of ritual, as well as Church and monastic influence.[2] The dynamics presented within these prayer books extend beyond the supposed vacuum of a wealthy layperson’s private chamber, and books of hours were objects of religious, economic, artistic and social exchange.

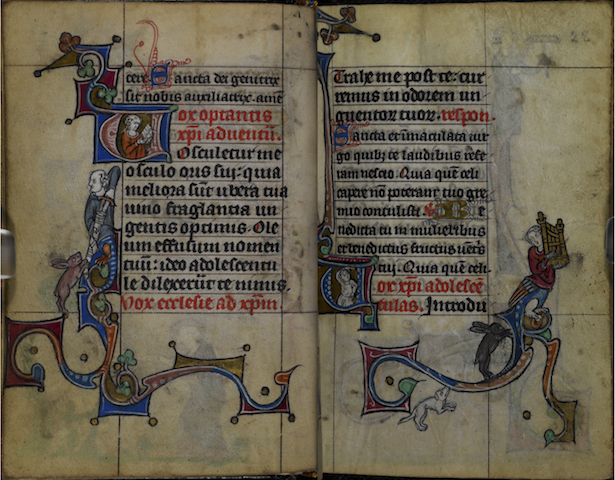

Made in the first decades of the fourteenth century, a small, highly decorated book of hours (London, British Library Stowe MS 17) presents an early example of what would, in time, become the most popular book of the later Middle Ages. It is also a masterful display of gothic illumination on a small scale (Fig. 1).[3] Produced in the Diocese of Liège, Stowe MS 17 is of a diminutive size (95 x 70mm), fitting snuggly in a person’s hands. It is the most densely decorated surviving book of hours from the area.[4] The numerous images of a praying woman in the pages suggest that Stowe 17 was probably originally intended for a female aristocrat.[5] An exploration of the textual and visual clues available in Stowe 17 itself exposes what can and cannot be uncovered about the original use and user of this manuscript.

The Manuscript

Stowe 17 has not been the subject of its own focused study, though it has appeared in surveys of hours and regional illumination, as well as catalogues for the Stowe collection. The British Library acquired the manuscript in 1883 with 1,084 manuscripts from Stowe House, owned by the Fifth Earl of Ashburnham.[6] Stowe 17 has often been referenced in general studies of gothic illumination. Studied particularly for its rich variety of marginal imagery, the manuscript has appeared in a number of published works on various gothic themes and decoration from the early 1950s to the present. Stowe 17 was often referenced by Lillian Randall in her indispensible book, Images in the Margins of Gothic Manuscripts, as well as by Horst Woldemar Janson in Ape and Ape Lore in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.[7] Most importantly for this study, Judith Oliver’s analysis of the Mosan Gothic manuscripts, Gothic Manuscript Illumination in the Diocese of Liège (c.1250–c.1330), provides an exploration of Stowe 17 as it relates to other books of the region.[8]

The Mosan region where Stowe 17 was made is best known by medievalists for its remarkable Romanesque metal work.[9] However, in the thirteenth century and into the fourteenth, it also became an important centre for the production of illuminated psalter-hours.[10] Stowe 17 was made between 1310 and 1320 as dated by the British Library, and shares characteristics with several other manuscripts from the region, most notably the now fragmentary BL Add 28784 and the ex-Kraus Hours (early 14th century), a book of hours now held at the University of Toronto that probably shared Stowe 17’s scribe.[11] Stowe 17 is one of the last and most extensively illuminated manuscripts from this tradition. The illuminator or illuminators of Stowe 17 were masters at working on a minute scale, with some of the figures measuring less than a centimetre high. The work throughout Stowe 17 is consistent in quality and style. Faces are often varied in the way they are drawn, sometimes within the same grouping on the same folio. Often, the nose connects to one of the eyebrows, but in other cases, the nose is a simplified, horizontal line in the centre of the face. The artist or artists preferred the three-quarters view of the face, with significantly fewer examples of profile view in the manuscript. In addition, they explore unusual perspectives to create depth, with some figures turned completely away so that the viewer sees only the back of the head or a small fraction of the face. The various poses and perspectives, as well as the many unique hybrids and exempla, make the manuscript an amazingly dynamic work. Based on relationships to other manuscripts and the unequalled variety, Oliver hypothesised that the artist had access to Flemish as well as Mosan model-books, though no such model-books now survive to confirm the theory.[12]

When handling Stowe MS 17, its first notable feature is its size. The margins of Stowe 17 have been cropped. Now housed in a tight modern binding, some illuminations teeter on the edge of the pages. Surprisingly small to the modern eye, this scale was below average for books of hours, but not unheard of in the late medieval period. It allowed the books to be portable, convenient for reciting the offices at the appointed times throughout the day. A book of hours of comparable scale to Stowe 17 is the roughly contemporary Hours of Jeanne D’Evreux (early 14th century).[13]

The manuscript is in a highly complete state, with no unfinished sections that would allow for evidence of process such as under-drawing. However, interruptions I found in my analysis of the text reveal that there are at least two missing folios: one between folios 125 and 126 in the midst of Psalm 113 during Vespers of the Little Office of the Virgin, and the other between folios 239 and 240, interrupting Psalm 64 in the Office of the Dead. There is visible wear on the manuscript, particularly in the corners of the pages. The most worn parts of the manuscript occur in the Office of the Dead and the French Ave poems located at the end. Folios 188, 197 and 243 have particularly fine decoration and are also the most notably worn, with some rubbing on the gold. When and by whom these pages were worn is now impossible to know, but with their particular splendour, the book may have been left open to these pages for periods of time or an owner may have often referred to them. The folios of the hour of Prime show significant wear, particularly at the beginning between folios 71 and 77, and on the last page before the beginning of Terce, folio 88. Such evidence of human handling provides a tantalising, yet ultimately elusive, insight into how Stowe 17 might have been used.

Textually, Stowe 17 does not fit any documented ‘use’, or geographical localisation according to the inclusion and order of the liturgical and calendar material. It has been localised to Maastricht, but no other manuscripts survive as examples of a ‘use of Maastricht,’ so the attribution is not particularly helpful. When compared to the seventy-five documented uses on the CHD Institute for the Study of Illuminated Manuscripts in Denmark, it is most textually similar to the Use of the Carthusian Order.[14] As is only found in the Carthusian Use, Stowe 17 includes Psalm 118 spread over half of Prime and all of Sext, Terce, and None.[15] Books of hours were rarely uniform in their content, and the varying images and prayers are the clues to understanding a manuscript’s unique context.[16] The text of Stowe 17 is psalm-heavy, with long offices.

The manuscript begins with a calendar written in French (fols. 2–13), followed by the eight offices of the Latin Office of the Virgin (see Appendix A). The first office, Matins, is extraordinarily long, spanning thirty-four pages. Following the Office are the traditional Penitential Psalms and the Gradual Psalms, the Office of the Dead, and finally two French poems. These two poems, ‘Ave qui ainz ne comenchas […]’ and ‘Ave rose florie […]’ are vernacular poetic translations of psalms, and are used in this context to praise the Virgin.[17] Including two or three such poems at the end of Mosan manuscripts was common, though the poem selection varies, perhaps at the discretion of the patron or the availability of exemplar.[18]

The manuscript is illuminated with sixteen full-page miniature illustrations. Four succeed the calendar, including the Nativity and then various saints. After this initial grouping, one miniature begins each office, before the Penitential Psalms, before the Gradual Psalms, before the Office of the Dead, and the last before the French poems. The miniature before Matins on folio 17v is of the Three Magi presenting gifts to the Virgin and Child in the historiated initial on the opposite folio. After that, the miniatures before each of the Hours of the Virgin are derived from the narrative of the Passion of Christ, with Lauds depicting Christ’s arrest.

The Passion cycle was the second most popular cycle of illustrations for the Little Office after scenes from the life of the Virgin, beginning with the Annunciation at Matins, the Visitation at Lauds, et al.[19] The miniatures in congruence with the texts divide the hours of the day into sacred time, marking out the hours of Christ’s crucifixion, which also took place over a day. Placing the Passion cycle with the hours seems to shift the devotional nature of the Office to have a larger focus upon Christ, though the Virgin is still a central figure in Stowe 17’s religious imagery.

After the Office of the Virgin, the miniatures continue: on folio 139v, a Noli Me Tangere proceeds the Penitential Psalms, then a woman kneels at a prie-dieu before the Gradual Psalms, and the Harrowing of Hell appears before the Office of the Dead on folio 187v. Before the French poems on folio 255v is the tale of Theophilus saved by the Virgin.[20] In all four of these cases, the miniatures are logical accompaniments to the text: Mary Magdalene was a famous penitent in the gospels, Christ rescuing souls from Hell provides hope for life after death, and the story of Theophilus exemplifies the mercy and goodness of the Virgin who is celebrated in the French poems.

The Owner Portraits

Depictions of owners within their books of hours were common markers of both possession and spiritual devotion in the fourteenth century. For owners of a personal book of hours, a physical presence within their own manuscript placed them near both the divine text and the devotional illustrations. In Stowe 17, the kneeling figure of an aristocratic woman appears on a total of ten folios, suggesting that she was the original audience, and perhaps the patron, of the book.[21] Most commonly, an owner portrait in a book of hours would occur on the first page of Matins, but it was not uncommon for people to appear numerous times in the pages of a manuscript.[22] In fact, in a twelfth century French book of hours (FR 1588) in the Bibliothèque National de France, the devotee appears fifty-one times.[23]

When discussing these images of an apparently real person in Stowe 17, questions of identity and likeness inevitably arise. Who was this woman, if it is indeed the same person in all the images? Are these really portraits? This brings to the fore issues of patronage as well as portraiture.[24] To begin, the differences between the people involved in the production of the manuscript must be delineated: patron, donor, scribe, artist and owner.[25] Sometimes the boundaries could be blurred and several of these roles might be performed by a single person.[26] For instance, the donor and patron might often be the same person, or even the donor, owner and patron.[27] However, in the case of Stowe 17, there is only enough visual evidence to support the claim that the kneeling woman was the original owner and audience of the manuscript. With images of her in prayer and at her prie-dieu, she is depicted as a devotee. It is still possible that she was the patron, but the manuscript might also have been a gift, perhaps from a mother or a husband on the occasion of marriage.[28] The images of the woman in the pages of Stowe 17 are not portraits in the sense that they convey some real or naturalistic likeness of a person’s physical features. Rather, these images were more like totems, surrogates for a person in body and spirit, standing in for them in the spiritual realm articulated on the page.

Alexa Sand has argued that these owner portraits were part of an inward gaze, the physical eyes seeing the spiritual self.[29] If these totems were for the soul, then the passage of time and the signs of ageing on the human body put no distance between a devotee and her image in the book. Sand also argues that these portraits ‘insist upon manuscript identity,’ tying the book to a single person, so that even future owners faced the permanence of the original owner’s image as a reflection of that owner’s hope for eternal life.[30] In another sense, the non-specific features of an owner portrait could allow future owners to also relate to it as a devotional aid.[31]

In the ten depictions of her in Stowe 17, a richly clad woman wearing a fur-lined cloak kneels, her hair covered by a white headdress, her hands clasped in prayer. In nearly all the portraits, she is depicted in the same style and scale as the marginalia. This creates a respectful distance between her and the religious miniatures, but her placement allows her to respond to them. Since she was not physically present at any of the biblical scenes she witnesses in the manuscript, the separation makes these scenes appear as a kind of spiritual vision brought on by intense contemplation, or speculatio.[32] Her presence directs the eye as well as demonstrates the performance of prayer for the viewer.

The colour of the woman’s clothing varies from image to image, but remains consistent in style. On several pages, she wears a red dress and a blue cloak, but elsewhere an orange dress and a red cloak, or a grey dress and a green cloak. This has multiple benefits for the design of the manuscript. Most important from an artistic standpoint, it adds brightness and visual interest. For the audience, it creates a sense of time within the manuscript, depicting the owner in prayer and devotion on any number of different days. Since a book of hours was intended for daily use, depicting the owner in different clothing using the book at different times is a visual way of having her carry out that spiritual task regularly.

A key element of the woman’s clothing remains consistent throughout the manuscript: the vair lining of her cloaks. Vair was a popular medieval fur, taken from the bodies of grey squirrels and sewn whole together so that their white bellies were exposed to form a pattern.[33] In some of the illuminations from Stowe 17, like on folio 98r in the image of Saint Martin, the tails of the squirrels can be made out hanging from the hems of the cloaks (Fig. 2). Beyond being a commonly used fur in the Middle Ages, however, vair was also a heraldic pattern. On heraldic coats of arms, a vair pattern resembles a series of blue bell shapes on a white background.[34] In Liège, vair was common in heraldry, related to the Belgian municipality of Awans, located in the Walloon province.[35] In Stowe 17, the fur is a sign of the highest honour, appearing on the lining of the cloaks of some of the saints as well as the devotee’s. On folio 168v, the owner even wears the vair as what would have been a very warm headdress. It may be that, given the prominence afforded the vair pattern in Stowe 17, as well as its heraldic presence in the region, the manuscript was commissioned by a person in whose coat of arms vair was a significant feature. Further supporting this heraldic connection to Walloon is the French calendar and prayers, which use the Walloon dialect.[36] However, it was by no means uncommon for vair to appear in manuscript illuminations, appearing as early as the 1220s in a French book of hours devotee portrait (Paris, Bibliothèque National de France, MS lat. 1073A, folio 165v).[37]

The first portrait in Stowe 17 occurs on folio 18r at the beginning of Matins (Fig. 3). The owner kneels in the lower level of a two-storey architectural space, hands clasped as she looks up at the historiated capital. Within the ‘D’ of Domine, across the page from the owner, the Virgin sits with the Christ Child in her arms. The Magi approach with gifts in the miniature opposite. Like the figure of the owner, the Virgin in Stowe 17 is shown wearing the vair-lined cloak, and in this image, both owner and Virgin wear red and blue with a white head covering. The owner is linked again to the Virgin by the blue background that frames them both. As the owner gazes up at the historiated initial, she looks simultaneously at the image of the Virgin and the beginning of the prayer that her real counterpart would be reciting.

The basic precedents established in this first portrait remain true in the others: the portraits often appear either in conjunction with a historiated initial or a full-page miniature, and the owner is often shown within some form of architecture. In the Passion miniatures, she appears with the Flagellation, the Piercing of the Virgin, the Resurrection, and a Noli me Tangere. Three out of four of these gospel scenes — the exception being the Flagellation —are moments specifically witnessed or experienced by women. Placed beside these scenes, the owner is put in the place of the Marys of the gospel narrative, herself a witness to the moments when God is revealed specifically to women.

Although in most of the portraits the owner simply kneels before a biblical scene, a few of the portraits present a key deviation from this pattern, adding another dimension and versatility to the woman’s representation within the manuscript. The first of these occurs on folio 140r, where the owner is placed within the historiated initial on the facing page of the Noli me Tangere miniature at the beginning of the Penitential Psalms. The owner kneels in confession before a priest, showing her penitence. Above them, the hand of God directs the action of the priest forgiving her sins.

The owner interacts directly with God again on folio 147r, in a particularly tender image where she makes a penitential appeal to Christ, and He, in the historiated initial of Psalm 50, looks at her and listens (Fig. 4). Psalm 50 begins: ‘Have mercy on me, O God, according to thy great mercy.’[38] Holding a scroll in one hand and making a gesture of teaching with the other, Christ looks directly down at the owner, acknowledging her faith and presenting the text itself as a guide for her spiritual life. In this undoubtedly comforting image, God is depicted as listening to and seeing her individually when she prays.

On folio 157v, at the beginning of the Gradual Psalms, the owner occupies her own full-page miniature as she kneels at her prie-dieu, praying to a crucifix (Fig. 5). Within the frame of her miniature, the owner is surrounded by music produced by the angels in the roundels at its four corners. Although not unusual in such personal prayer books, this image shows the woman in a solitary act of personal piety, unlike all the other portraits Stowe 17. She is the focal point, and the subject of the image is her own ritual worship. This portrait might also have been instructional, demonstrating the proper location and demeanour for prayer. With this page acting as the set stage, the portrait performs for the viewer the act of prayer.

The owner portraits in Stowe MS 17 are numerous and informative in the way they function within the manuscript. The woman they describe is a person of status and effective faith, but also one who is interested in representation and in her own place within both her world and the higher order. The portraits depict not only a woman devoted to her own spiritual practice, but also a woman whose piety is heard and responded to by God. The female devotee in Stowe 17 acted as a surrogate for her real, praying counterpart. Shown in a state of constant, perfected worship, she was both an ideal to be worked towards and an image of self-identification. Through seeing herself on the pages during her daily prayers, the woman looking at Stowe 17 could see herself in the schema of a greater, spiritual reality articulated in the book, helping her gain both a feeling of intimacy with the figures in the miniatures and define her own sense of self.

Beyond the owner portraits, the marginalia often seems geared towards the owner of the manuscript. Humorous and varied, the margins of the manuscript are densely populated with a variety of female figures: mermaids, female hybrids, good nuns, bad nuns, courtly ladies, female musicians, saints, a virgin with a unicorn, women armed with swords and with books. The virtuous and the indecorous crowd together, often intermingled with jousts and monsters, animals and architecture. Spindles and distaffs, traditional symbols of the women’s craft of weaving, appear over a dozen times in both comical and serious contexts. The first appearance of the distaff in Stowe 17 is held by an ape on 30v, but a page later, Eve is shown using one as her children play at her feet. In this context, the spindle is a symbol of female domesticity and labour, perhaps also alluding to married status. However, the distaff could also be humorously portrayed as a women’s weapon. On folio 133r, two female hybrid creatures battle with distaffs, one hitting the other in the face. Medieval images exist of women chasing men and hitting them over the head with spindles.[39] In Stowe 17, the spindle seems alternatively to be used for industry, with people of both genders seated and holding them, like on folio 113r, and at other times, comedy and gender commentary. A woman on 64v hikes up her skirts to reveal her bare legs, brandishing a spindle at the opposite page, where Renard the fox captures Chanticleer the cockerel. On 140v, an ape with breasts and wearing a berbette dangles a distaff. This image may be a sexual innuendo to the ‘groanings’ of the psalm-writer during his labours, ‘I have laboured in my groanings, every night I will wash my bed.’[40] Apes were also a symbol of impurity and lust.[41]

Though an in-depth examination of all the images contained in the book lies outside the scope of this article, it seems useful here to mention at least one central theme in the scheme. Along with the most obvious example of the Virgin Mary, illustrations of motherhood often crop up in the religious imagery of Stowe 17. For instance, St Margaret, the patron saint of childbirth, bursts out of the dragon on folio 156r during Psalm 142 of the Penitential Psalms. The pit of the dragon’s belly may relate to the section of the text above: ‘Turn not away thy face from me, lest I be like unto them that go down into the pit’.[42] The margin of folio 261v again speaks to the grief and trials of motherhood: the Massacre of the Innocents (Fig. 6). In the manuscript illustration, Herod points as one of his soldiers raises his sword to kill a baby, roughly jerking its arm. The baby’s mother cowers in distress, gripping her already blood-stained child. It is a gruesome and violent image of a mother losing her baby, an event that was hardly uncommon in the fourteenth century, when many children did not survive infancy. However, the story is redeemed on the next folio with a sweet image of resolution, in which the soul of the baby is seen being taken to Heaven by smiling angels (Fig. 7). For a woman who may well have lost children during her own lifetime, this image would probably be a very comforting one, as the soul of a dead child was taken into the care of God.

Stowe MS 17 and its purpose

It is difficult to determine how, and how often, the original owner actually prayed through the offices in Stowe 17. As has been noted, there is some wear on the manuscript, but it is not clear when or how it occurred. Some owners of books of hours were advised to pray Matins, Lauds and Prime upon waking in the morning, others appear to have prayed all eight hours at the beginning of the day.[43] Beyond religious use, books of hours did become quite fashionable as an accessory, a choice object for noble ladies as a status symbol.[44] This is evidenced by the often-cited poem by Eustache Deschamps about a courtly lady who seems more concerned with the gold decoration of her book’s binding than its religious contents:

An Hours of the Virgin must be mine/Matched to my high degree /The finest the craftsman can manage/As graceful and gorgeous as me: Paint it with gold and azure […] So the people will gasp when I use it/ ‘That’s the prettiest prayer book in town.’[45]

Perhaps just as important as seeing oneself inside the book was another visual dynamic: that of being seen by others with such a beautiful and costly object. While it could be true that Stowe 17 was merely a prop in the theatre of socio-economic performance, those attempting to study the way that books of hours like Stowe 17 were meant to be used can only go so far with the argument that people did not really use them. The cost and thought that went into the interior text and decoration of such objects seems to indicate more investment than that. It will be more profitable to try and understand the way Stowe 17 might have, and likely did, function.

Virginia Reinburg suggested two basic purposes for the book of hours: to record devotional practice and provide a personal script for prayer.[46] It has already been demonstrated that Stowe 17 represents a more complex layering of text and image than this, but the idea of a script remains useful for understanding the information we can and cannot glean from looking at such a manuscript today using notions of literacy and practice. In the fourteenth century, northern Europe was a fledgling literate culture, not yet fully lodged in text. The oral component of a book of hours is essential to understanding the way someone might access the contents. For a medieval reader, words were still firmly rooted in sound, with text presenting a symbolic language to aid the memory: ‘Like musical notation, medieval letter script was understood to represent sounds needing hearing.’[47] Images and words functioned in a similar way, as signifiers for truths that they represented rather than embodied. For the modern viewer of a book of hours, the text is often more easily accessible than the images, simply because we have inherited a knowledge of the written language of Latin but now lack some of the symbolic language skills needed for easily interpreting all the images. The medieval viewer may have struggled over both text and image, encouraging long-looking and careful work to decipher the codes of information in their book. It was designed to be a ponderous process, spread over a daily routine that could last years, meant to reveal, inspire and entertain on multiple occasions. Wisdom was not contained in books, but rather books were tools that could be used in the process of storing up and internalising wisdom.[48]

To use Stowe MS 17, the reader would have needed not only their own vernacular language of French, but also at least a ‘phonetic literacy’ of Latin, that is, an ability to decode it by reading aloud.[49] The basics of literacy were often taught at home by the mother, and this level of Latin knowledge could have been gleaned from attending Mass and learning devotional recitations.[50] For someone with a limited knowledge of Latin, perhaps understanding only a few words, the repetition of the psalms in the holy language of scripture could still be a cathartic and comforting ritual. Praying in Latin could have the ability to transport, lifting the devotee out of the mundane world of their own vernacular speech and into a verbal religious space. William Ong, who researched the transition of societies from oral to textual communication, explained this power of Latin succinctly: “[it is] a medium insulated from the emotion-charged depths of one’s mother tongue, thus reducing interference from the human life-world and making possible the exquisitely abstract word.”[51]

Stowe 17 and other books of hours can provide a plethora of information about how the ritual of praying the Daily Office was performed, but its textual nature also limits what we can know about what was, at its heart, an oral service. What survives now is only a record of a ritual, an after-image of a habitual devotion spoken aloud. It is rich archival evidence, but with severe limits. Written text, for one, is a simplification of the rhythms of speech.[52] Just like a script, we cannot know from Stowe 17 how praying the hours would have sounded. Monastic communities sing their services, and Stowe 17 does include hymns and images of musical instruments; might the Offices have been sung? Christopher de Hamel describes the process as a kind of mumbling through, but Stowe 17 includes no notations for cadence or volume. Though the owner portraits seem to denote a prayerful isolation, books of hours were used in both public and private settings, which would also affect the way Stowe 17 functioned.[53] A few examples of other praying figures in the margins, like the robed male figure praying alongside the owner on folio 271v, suggest other presences in the book, perhaps family or clergy, a reminder that Stowe 17 was a personal book owned in the context of multiple communities, a complex object with both interior and performative significance.[54] Stowe 17 is a script with no stage directions, a relic of a now mysterious one-woman play. How she moved through the process, lingered over some passages, skipped others, shared it with family or friends, shut her eyes or opened them, touched or even kissed the images for comfort, are lost to the time between now and then. The artefact that survives tells only a tantalisingly fragmented story.

It can be said that Stowe 17 has a strong emphasis on both religious and non-religious female imagery and that the owner’s gender likely facilitated this. The multiple portraits point to a woman with a desire to be seen, and the pages of Stowe 17 repeatedly assert her presence and her identity, making her perspective an indelible part of engaging with the manuscript. Its size and layout limits the audience to one viewer at a time, so small that it would be next to impossible to use in the education of children or viewing with another person. This gives Stowe 17 an intimate viewing experience, a moment of individual connection with the manuscript. Gazing at herself over a number of pages may even have contributed to a personal idea of selfhood.[55]

Conclusion

Stowe MS 17 is one of the finest and most fully decorated books of hours surviving from the early fourteenth century. Made at an early moment in the production of this kind of book, it represents an excellent example of the versatility of both text and design for a book of hours, a genre that would continue to demonstrate great multiplicity of individual conception up until the introduction of the printing press and even beyond. Stowe 17’s images cover an amazing emotional breadth, from the maternal grief displayed in the Passion miniatures, to the penitential devotion of the owner portraits, and finally the humour and spontaneity of many of the other marginal images. Overall, it is a manuscript that, through both text and image, seems to advocate spiritual hope, meant to inspire the faith of its owner through daily ritual and contemplation. It represents a culmination of the Mosan psalter-hour tradition as one of only three surviving fourteenth century Mosan books and by far the richest.[56] Finally, it presents a tantalising opportunity to study issues of female spirituality and perspective in the early fourteenth century.

Appendix A: Graph Demonstrating Textual Contents or “Use of Stowe 17”[57]

*Folios featuring owner portraits are denoted with asterisks

| Office | Folio | Text |

| Matins | *18r | Matutinum [Ps.94, 23, 44, 45, 86, 95, 97]

Antiphona Domine labia mea aperies. Et os meum annuntiabit laudem tuam. Deus in adiutorium meum intende. Domine ad adiuvandum me festina. Invitatorium Ave maria gra plena dominus tecum… Hymnus (No Hymn) Ant. ps. 8: Lectio. [Evangelium Secundum Lucam] “In illo tempore …” |

| Lauds | 53r | Ad Laudes [Pss. 92, 66, 148, 150]

Antiphona Domine ad adiuvandum me festina. Gloria pater. Sicut era. Sicut lili Capitulum [Canticum Trium puerorum (Daniel 3)] Hymnus “Oh Gloriosa Domina…” Antiphona super Benedictus “Beata Dei genitrix Maria, virgo perpetua” Oratio [Canticum Zachariae: Luc 1:68-79] |

| Prime | *72r | Ad Primam [Pss. 53, 118.1–32]

Antiphona Deus in adiutorium meum intende. Domine ad adiuvandum me festina. Gloria Patri. Hymnus “Agnoscat omne speculum venisse vitae …” Capitulum Athanasian Creed R. Beata progenies ex qua Christe natus est quem gloriole virgo que celi rege Antiphona Gaude Maria virgo, cunctas haereses sola interemisti in universo mundo. Oratio “Oremus Sancta Maria mater Domini noster Jesu Christu …” |

| Terce | 89r | Ad Tertiam [Ps. 118.33–80]

Antiphona Deus in adiutorium meum intende. Domine ad adiuvandum me festina. Gloria Patri. Hymnus “Specie tua et pulchritudine …” Capitulum “Maria ventre concepit ubi fideli semine quem totus…” R. Gloria tibi domine. Qui natus est virgine cum patre et sancto spiritu in sempiterna secula amen. Beata Maria. Oratio “Diffusa est gratia in labys tuis …” |

| Sext | *99r | Ad Sextam [Ps. 118.81–113]

Antiphona Deus in adiutorium meum intende. Domine ad adiuvandum me festina. Capitulum No Capitulum Oratio “Protege Domine famulos tuos…”] |

| None | 108r | Ad Nonam [Ps. 118]

Antiphona Deus in adiutorium meum intende. Domine ad adiuvandum me festina. Hymnus “Adam vetus quod polluit…” Capitulum Ecclesiasticus 24 R. Elegit eam deus et preelegea. Et habitare eam facit in tabernaculo suo. Oratio “Famulorum quorum quaesumus Domine …” |

| Vespers | 117r | Ad Vesperas [Pss. 110, 111, 112, 113]

Antiphona Deus in adiutorium meum intende. Domine ad adiuvandum me festina. Gloria. Capitulum Canticum Mariam Hymnus Salve Regina Oratio “Per eundem Dominum nostrum Iesum Christum filium tuum…” *130v |

| Compline | 131r | Ad Completorium [Pss. 4, 30.2–6, 90]

Antiphona Converte nos Deus salutaris noster. Et averte iram tuam a nobis. Deus in adiutorium meum intende. Domine ad adiuvandum me festina. Gloria Patri. Capitulum Canticle Simeonis, Luc 2 Hymnus “Ecce nunc benedicite Dominum …” Antiphona super Nunc dimittis Post partu virgo inviolata per mansisti dei genitrix intercede pro nobis. Oratio Salva nos quis omnibus deus ut intredente pro nobis beata et gloriosa semper quiz virgine dei genitre maria … |

| Penitential Psalms | *140r | [Pss. 6, 37, 50, 101, 129, 142]

*147r (Pss. 50) *157v |

| Gradual Psalms | 158r | [Pss. 119, 120, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133]

*168v (Pss. 130) |

| Office of the Dead | 188r | [Pss. 114, 119, 120, 129, 137, 5, 6, 7, 22, 24, 26, 34, 39, 41, 40, 64, 62, 66, 148, 149, 150, 145]

Antiphona Dominus custodiat; Si iniquitates; Capitulum Canticum Luke 1 Antiphona Dirige Domine Deus; Convertere Domine; Nequando rapiat ut leo Capitulum Job 7; Job 10; Job 13; Job 14 Antiphona Delicta inventutis meae; Credo videre bona R. Absolve, Domine animas Capitulum Job 17 Antiphona Complaceat tibi Domine; Sitivit anima mea ad Capitulum 1 Cor 15:20-31; 1 Cor 15:32-38; 1 Cor 15: 51-57 Capitulum Isaiah 38 Hymnus Luc 1, Song of Zachariah Oratio (non-standard, summary here in English for ease) Prayer for a dead woman; Prayer forgiving servant; Prayer for parents; Prayer for brothers and sisters of our congregation; Prayer for servants of god for forgiveness; Prayer for forgiveness |

| Marian Poems | *256r | “Ave qui ainz ne comenchas …”

“Ave Rose Florie …” *271r |

Citations

[1] Roger S. Wieck, Painted Prayers: The Book of Hours in Medieval and Renaissance Art (New York: George Braziller, 1997), 9.

[2] Colin Richmond, ‘The English Gentry and Religion, c. 1500,’ in Religious Beliefs and Ecclesiastical Careers in Late Medieval England, Christopher Harper-Bill, ed., (Woodbridge: Boydell Press 1991), 121–150; Virginia Reinburg, ‘Prayers and Books of Hours’, in Time Sanctified: The Book of Hours in Medieval Art and Life, Roger S. Wieck ed. (New York: Geroge Brazilier, 1997), 39–45; Virginia Reinburg, French Books of Hours: Making an Archive of Prayer, C. 1400–1600 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 6.

[3] Hereafter referred to as Stowe 17.

[4] ‘Stowe MS 17,’ British Library Digitised Manuscripts, (Published n.d., Accessed 30/3/16 http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Stowe_MS_17).

[5] ‘Stowe MS 17,’ British Library Digitised Manuscripts.

[6] ‘Stowe MS 17,’ British Library Digitised Manuscripts.

[7] Lilian M. C. Randall, Images in the Margins of Gothic Manuscripts (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966), 37, pls V.14-15, CVI.509, CXXXIV.638; Horst Woldemar Janson, Apes and Ape Lore in the Middle Ages and Renaissance (London: Warburg Institute, 1952), 67, n. 104, 158 n. 5, 173, 188–94 n. 14, n. 25, n. 32, n. 49, n. 51, n. 60, n. 62, n. 67, 197 n. 98, n. 101, n. 135.

[8] Judith Oliver, Gothic Manuscript Illumination in the Diocese of Liège (c. 1250–c. 1330), vol. 2. (Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters, 1988), 32–29; 86–90; 173–193; 204–205; 269.

[9] Oliver (1988), 19.

[10] Oliver (1988), 20.

[11] ‘Stowe MS 17,’ British Library Digitised Manuscripts; Judith Oliver, ‘Reconstruction of a Liège Psalter-Hours,’ in The British Library Journal, 5, 2, (Autumn 1979), 107–128; Oliver (1988), 190.

[12]Oliver (1988), 189.

[13] ‘The Hours of Jeanne D’Evreux,’ The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (Published n.d., Accessed 10/5/2016, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/54.1.2/).

[14] Erik Drigsdahl, ‘CHD Tutorial on Books of Hours,’ CHD Institute for Studies of Illuminated Manuscripts in Denmark (Published 1997, Accessed 5/5/16, http://manuscripts.org.uk/chd.dk/tutor/index.html). See also: Gregory Clark and John H. Plummer, ‘Beyond Use: A Digital Database of Variant Readings in Late Medieval Books of Hours’ (Published 2013, Accessed 16/7/2017, http://arthur.sewanee.edu/BeyondUse/index.php).

[15] Drigsdahl, CHD.

[16] Nigel Morgan, ‘Texts and Images of Marian Devotion in Fourteenth Century England’, in England in the Fourteenth Century: Proceedings of the 1991 Harlaxton Symposium, Nicholas Rogers, ed. (Stamford: P. Watkins, 1993), 30–53, 35; Adelaide Bennett, ‘Making Literate Lay Women Visible: Text and Image in French and Flemish Books of Hours, 1220–1320,’ Thresholds of Medieval Visual Culture: Liminal Spaces, Elina Gertsman, Jill Stevens, eds. (Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2012), 125–158, 128.

[17] Oliver (1988), 38.

[18] Oliver (1988), 38.

[19] Eamon Duffy, Marking the Hours: English People and Their Prayers 1240–1570 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 12.

[20] Oliver (1988), 255 – 56.

[21] Stowe MS 17, 18r, 72r, 99r, 130v, 140r, 147r, 157v, 168v, 256r, 271r.

[22] Sandra Penketh, ‘Women and Books of Hours,’ in Women and the Book: Assessing the Visual Evidence, Smith, Lesley, and Jane H. M. Taylor, ed. (London: British Library, 1997), 266–282, 271.

[23]Adelaide Bennett, ‘Issues of Female Patronage: French Books of Hours, 1220–1320,’ Patronage, Power, and Agency in Medieval Art, Colum Hourihane, ed. (Princeton: Index of Christian Art, 2014), 241.

[24] See Stephen Perkinson, Likeness of a King: A Prehistory of Portraiture in Late Medieval France (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

[25] Colum Hourihane, introduction to Patronage, Power, and Agency, (Princeton: Index of Christian Art, 2014), xix.

[26] Hourihane, xix; Jonathan J. G.Alexander, Medieval Illuminators and Their Methods of Work (Hartford: Yale University Press, 2004).

[27] Hourihane, xix.

[28] Susan Groag Bell, ‘Medieval Women Book Owners: Arbiters of Lay Piety and Ambassadors of Culture,’ Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 7, 4 (1982), 742–68, 758.

[29] Alexa Sand, Vision, Devotion, and Self-representation in Late Medieval Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 11–13.

[30] Sand, 166.

[31] Sand, 6.

[32] See Jeffrey Hamburger, ‘Speculations on Speculation: Vision and Perception in the Theory and Practice in Mystical Devotion’ in Deutsche Mystik im abendländischen Zusammenhang, Walter Haug & Wolfram Schneider-Lastin, ed. (Tübingen: Niemeyer, 2000), 353–408.

[33] Elspeth M. Veale, The English Fur Trade in the Middle Ages (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1966), 228.

[34] See Alison Stones, ‘The Full-Page Miniatures of the Psalter-Hours New York, Morgan Library, L M. 729: Programme and Patron,’ The Illuminated Psalter: Studies in the Content, Purpose and Placement of Its Images, ed. Frank O. Buttner (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004), 281–307.

[35] Louis De Crassier, Quelques Caractéristiques De L’héraldique Liégeoise (Liège: Poncelet, 1909), 7; Alison Stones, ‘Note on Heraldry of a Very Special Gauvain,’ in Li premerains vers: Essays in Honor of Keith Busby, C.M. Jones and L. E. Whalen, ed. (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2011), 301–43.

[36] Oliver (1988), 269.

[37] Bennett (2012), 131.

[38] Psalms 50.1.

[39] David Herlihy, ‘Women’s Work,’ in David Herlihy, Women, Family, and Society in Medieval Europe (Providence, RI: Berghahn Books, 1995), 96.

[40] Psalms 6.6.

[41] Janson, 146.

[42] Psalms 142.7

[43] Smith, 2.

[44] Penketh, 269.

[45] Eustache Deschamps, trans. Duffy, 21; Erik Inglis, The Hours of Mary of Burgundy (Turnhout: Miller, 2000), 60–1.

[46] Reinburg (2012), 112.

[47] Michael Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record: England, 1066–1307 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1st ed., 1979), 285.

[48] Anneke Mulder-Bakker, ‘The Metamorphosis of Women: Transmission of Knowledge and the Problems of Gender,’ in Pauline Stafford and Anneke Mulder-Bakker eds.,Gendering the Middle Ages (Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers, 2001), 112–143 (117).

[49] Reinburg (2012), 142.

[50] Bell, 756; Virginia Reinburg, ‘Prayers and the Book of Hours,’ in Time Sanctified: The Book of Hours in Medieval Art and Life,’ ed. Roger S. Wieck (New York: George Braziller, 1988), 39–45 (40); Adelaide Bennett (2012),135.

[51] William Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word (London: Methuen, 1982), 114.

[52] Ong, Orality, 101.

[53] Duffy, 57.

[54] Fols. 108r, 256r, 271r, 266r, 271v.

[55] Sand, 203.

[56] Oliver, 190.

[57] After Erik Drigsdahl, ‘H-V form for notating Hours of the Virgin’, (Published 1997, Accessed 2/6/16, http://manuscripts.org.uk/chd.dk/tutor/hvform.html).