Anglo-Dutch artist Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912) first visited Pompeii in 1863 while on honeymoon with his second wife. Alma-Tadema’s lifetime corresponded with a period of renewed interest in the history and archaeology of the Italy’s ancient past. In the 1860s, excavation of Pompeii took off and was carefully organized and documented with scientific rigour by project director Giuseppe Fiorelli, a marked change of strategy from the haphazard exploration of previous generations. It was Fiorelli who realised that the bodies of Pompeii’s residents had created cavities in the hardened lava, and that these could be filled with plaster to create the memorable casts that are so haunting to any visitor of that ruined city. The discovery injected a real sense of humanity into the site, and set up a unique space in which to discuss the immediacy of history and memory. Alma-Tadema was fascinated with Pompeii, returning several times. While in Italy, he observed digs, measured buildings, and sketched objects to produce extensive documentation of his own, and many of these drawings can now be found among his papers at the University of Birmingham.

The artist’s Pompeian pictures form a large part of his body of work until about 1880. An earlier generation of scholars characterised Alma-Tadema’s works as mere images of ‘Victorians in togas’, in line with a ‘mirror of history’ reading of the interaction between the nineteenth-century viewer and the past. This interpretation sees the Victorian notion of history as a sort of stage set on which to act out contemporary problems.[1] Though made more nuanced since, the understanding of the classics as ‘the furniture of the mind’ for an educated Victorian – a sort of presentist toolbox of received values – remains a dominant thread in reception studies.[2] This phrase is Simon Goldhill’s, and his work goes some way to destabilising the understanding of the relationship between antiquity and the nineteenth century as a monolithic, usually imperial one, incorporating instead multiple classicisms, both conservative and radical. Nonetheless, the idea of the past as a toolbox used by Victorians to either make judgements or justify these decisions remains a dominant thread that can be further unpicked.

This paper argues that the artist had a unique way of engaging with the ancient world; in Alma-Tadema’s paintings, the past is populated by living bodies and its construction is more indebted to contemporary studies of memory and recollection than has previously been acknowledged. Crucially, while the ‘mirror of history’ model is based on the idea that the past is passive, remote and dead, merely propped up as the setting for nineteenth-century cultural debates, Alma-Tadema restores nearness and resurrects the everyday life of the ancients. While indebted to secondary scholarship for the careful attention to the facts and figures of Alma-Tadema’s life, this paper consciously turns away from many of the previous attempts to identify an ideology for the artist’s work, focusing instead primarily on nineteenth-century source material, including letters, interviews, reviews, and the archival material owned by Alma-Tadema to inform the discussion.[3] Both the mental and physical remains of the ancient world had an impact on Alma-Tadema’s work. The idea that Alma-Tadema presented a revitalized image of a previous era is not a new one, and was recognized by the first critics to discuss his works, and many of these appear in this essay. Building on this proposition of immediacy, this paper argues that Alma-Tadema communicates to the viewer his idea of the past as though recounting his own memories. Alma-Tadema’s focus on the ancient world in general, and Pompeii specifically, is evaluated in terms of Victorian scientific and philosophical theories of memory and imagination; his technique sheds light on how the artist engaged with these three concepts while creating a painting. Together, these elements work to highlight the artist’s capacity to resuscitate ancient life while suggesting a relationship between the body of the ancient Pompeian, the artist, and the viewer. For Alma-Tadema, the past was experienced not only through the visual, but also through visceral impressions of body and mind which were crucial to his participation in an aesthetic project that was meant to transcend time.

Memory and Imagination

The attempt to explain the mechanism of memory has roots in the philosophy of Aristotle, who recognized a distinction between memoria and anamensis, which are commonly both referred to as ‘remembering’. The first term relates to how information is stored, while the second is reserved for the act of recovering that knowledge at a later time.[4] As with many disciplines, the Victorian era applied scientific principles to the study of memory, with scientists such as Henry Maudsley, William Carpenter, and Herbert Spencer all considering the issue as part of larger projects to explain psychology and the work of the mind.[5] Though this article is primarily interested in memory as a tool of reception in the nineteenth-century understanding of the classical past, it is worth briefly acknowledging the rich academic field of memory studies as well. In particular, Maurice Halbwachs alerts us to the fact that any act of remembering exists in the present rather than in the past, and that there is no ‘true’ recollection of the past but rather one that is constructed out of the pressures of the present. This might lead to a conclusion that Alma-Tadema’s use of the ancient world as a subject is little different from other Victorian conceptions of the past, but this article argues it is the way in which this engagement occurs, informed by mind and body rather than text or politics, that sets the artist apart.[6]

The Sculpture Gallery, an oil on canvas work painted in 1874, provides a point of entry into the discussion of memory and history.[7] It was exhibited at the Paris Salon in the same year, and at the Royal Academy in London in 1875. As the body and mind had a particular impact on Alma-Tadema’s perception of history, the human figures in The Sculpture Gallery are of particular interest. Nineteenth-century observers noted that five of them, including the two seated on a bench to the left and the standing group of a woman with two children, appear to be portraits of the artist and his family.[8] While elements such as this may have attracted the reductive categorisation of Alma-Tadema’s works as scenes of ‘Victorians in Togas’, the painting has little in common with more conventional Victorian or Grand Manner history painting. It is far more specific in reference to place, and vague in reference to subject. Here, the famous faces of myth, literature, and history situated in an idealised landscape have been replaced by ordinary citizens in an archaeologically informed space. Other than the northern European physical type, the figures do nothing to make themselves seem out of place in the scene, and interact with the environment in a way that suggests it is their own normal, everyday life. In fact, the painting is not about the figures of Alma-Tadema and his family as such, they are merely part of a larger project of reconstructing the quotidian past.

By placing himself in this scene of the ancient world, Alma-Tadema invites the idea that the space represented on the canvas is his personal, first-hand vision of the past. Though initially the concept may sound farfetched, it is one corroborated by the artist himself and linked closely with scientific thought of the day. William Carpenter, writing in the same year the picture was painted, explained how repeated processing of external information could come to seem as vivid as a memory. He described a situation in which a person is told of his actions at a moment in time that he can no longer remember. As the information is repeated many times, the individual comes to regard the anecdote as his own memory.[9] Carpenter immediately linked this idea to the creation of a work of fiction and we might also assume it applied to the completion of a painting. He declared:

In like manner, when the Imagination has been exercised in a sustained and determinate manner – as in the composition of a work of fiction – its ideal creations may be reproduced with the force of actual experiences; and the sense of personal identity may be projected backwards (so to speak) into the characters which the Author has evolved out of the depths of his own consciousness.[10]

In other words, characters share awareness with their creator. Something similar occurs in Alma-Tadema’s painting, though in this case the figures are not entirely fictional, and it is not only the creator who imposes consciousness on the subjects, but the converse as well.

Memory and imagination are both critical to the artistic process; at the same time, the former is engaged to fashion works that connect with a universal aesthetic, while the latter allows for the creation of artworks that are unique. Alma-Tadema’s in-depth study of archaeological photographs can be regarded as a mental process similar to the creation of personal memories. Alma-Tadema described his artistic process as possessing a strong mental element, which allowed him to bridge the temporal gap between himself and the past. In one interview, he explained that his revival of ancient life was achieved in part ‘by transporting my mind into far off ages’, driven by the motivation that, ‘I must not only create a mise-en-scene that is possible, but probable.’[11] In another interview, he acknowledged his familiarity with the world he painted, saying, ‘I know Pompeii by heart.’[12] The language of both of these quotes situates the artist in the ancient world, if not physically, as in A Sculpture Gallery itself, than certainly in terms of psychological state. In fact, it might be possible to view Alma-Tadema’s creation of two home-studios in historical styles at least in part as an attempt to remedy this physical and mental discrepancy.[13]

Alma-Tadema was so dependent on these constructed memories that he avoided travelling; he feared that impressions of the modern world would cloud his vision of the past. He explained:

I have never been to Greece or the Orient from the fear that I should not be able to see the ancient life there for the crowds of living people and things of to-day. Even Rome is becoming hopelessly modern in that sense—on my last visit in 1866 I was much less able to discover for myself the life of the ancient city.[14]

This danger of present overwhelming past did not exist in Pompeii, which explains why it was one of the few sites that Alma-Tadema did continue to visit. In other ancient places, even Rome itself, there is more evidence for how the past flows into the present, with Christian churches built on top of pagan places of worship, for example. Pompeii however, was frozen in a singular moment, and provides an encounter with the remains of individual residents in their original dwelling places, challenging the capacity of the passage of time to render people anonymous.

While the creation of memory is one element of the artistic process with a scientific corollary, imagination also plays a significant role, and is the key to the originality of Alma-Tadema’s works. By painting figures that both resemble nineteenth-century figures and yet are seamlessly integrated in the antique environment, and by creating domestic spaces inspired by the ancient world, Alma-Tadema makes the case that the bodies on the canvas and the bodies in his home-studio occupy a common temporality in which past and present are not distinct. His reviewers and biographers often declared that his goal was to demonstrate a universal human nature, which can be proposed as a possible motivation for the blurred sense of time. Georg Ebers stated, ‘The figures he shows us usually wear the garb of ancient times, yet they are neither old nor new, but purely human, and when he makes the child laugh or the widow weep, it is not only a little Roman or a Frank princess who laughs or mourns, but the careless child or the woman who has lost her husband, as they must have laughed or wept in any age of the world.’[15]

In terms of both mind and body, Alma-Tadema situated himself simultaneously in the past and present, and implored his viewers to join him in this temporally ambiguous space. To build a believable world in which this is possible, he used imagination to reassemble the city of his memory. Alma-Tadema’s use of archaeological source material is well documented. In addition to trips to Italy and studies in institutions such as the British Museum, between 1850 and 1910 the artist collected 5,300 photographs of ancient sites and artefacts, which he arranged in 168 albums, now housed in the archives of the University of Birmingham.[16] Elizabeth Prettejohn has matched many of the items in The Sculpture Gallery to photographs in his collection, and mentions that the silver bowl, the central carved tazza, as well as much of the architecture and sculpture are based on, though often not exact copies of, items that were readily available to Alma-Tadema.[17] Mimicking the photographic albums themselves, which were arranged according to theme rather than age or specific place of origin, Alma-Tadema combines these elements in a fictional scene. As has been noted before, the quality of reality evident in this and other paintings is largely due to the lavish materiality of the artefacts. Much has been said in Prettejohn’s assessment about the virtuosic handling of marble in the artist’s work, which here make the environment seem indestructible. Although Alma-Tadema’s real memories of such spaces were based entirely on looking at fragments and ruins, he possessed an ability to imagine a believably intact and inhabited space. In this case, memory and imagination enhance tangibility, rather than the ephemeral.

Replicated historical detail and creative enterprise may seem at odds with each other. Vern Swanson challenges this idea, noting of the artist’s method, ‘It was less an emotional than a constructive imagination, less vehement and romantic than analytic and realistic. But if imagination is the power of realising that which is unknown, then Alma-Tadema possessed it in abundance.’[18] Unwittingly, Swanson references some of the central tenants of the Victorian study of the imagination. Alma-Tadema’s originality is further defended by a contemporary critic, who said:

It is the imagination that really does the work of reconstruction. The result is too concrete to have been reached by abstract intellectual methods. The artist has brooded over his knowledge till it lived in visible form before him. To see at all what is unfamiliar, what cannot be seen by its reflection in the eyes of many, demands real imagination.[19]

This explanation returns to the idea that the past existed as a form of memory for the artist himself, and links it with the idea that imagination was the tool that made the paintings similarly viable for the viewer. The newspaper review’s reference to the past living before Alma-Tadema’s eyes emerge as one of the defining features of his unique construction of the past.

The Victorians conceived of memory and imagination as part of the same mental phenomenon, and this became a dominant part of the Victorian understanding of the mind. Maudsley observed succinctly:

How much of what we call memory is in reality imagination! When we think to recall the actual, the concrete, it is often the ideal, the general, that we produce; and when we believe that we are remembering, we are influenced by the feelings of the moment, and not able to reproduce the feelings of the past, misremembering. The faculty by which we recall a scene of the past, and represent it vividly to the mind, is at bottom, the same faculty as that by which we represent to the imagination a scene which we have not witnessed.[20]

In the same section, Maudsley links art and science closely, using fine art as an example to explain the bond between reality and imagination. He wrote, ‘When the artist embodies in ideal form the result of his faithful observation, he has, by virtue of that mental process through which general ideas are formed, abstracted the essential from the concrete, and then by the shaping power of imagination given to it a new embodiment.’[21] Thus, the translation from personal observation, or ‘memory’, into work that can be widely appreciated by use of imagination was the chief creative strength of any artist.

For Alma-Tadema, past and present did not have a strictly linear interaction. This perception was also explored in depth by many of Europe’s great nineteenth-century thinkers. Thomas Carlyle, for one, stressed that knowing more about the past always brought the present in closer to it. He stated, ‘For the whole Past, as I keep repeating, is the possession of the Present; the Past had always something true, and is a precious possession. In a different time, in a different place, it is always some other side of our common Human Nature that has been developing itself.’[22] For Carlyle the past is not entirely separate from what is current, but continues to exist and shape human actions in the present. Similarly, for Nietzsche, writing at about the same time Alma-Tadema was painting, linear time was even more irrelevant. He theorised that the present and future were always simply an eternal repetition of the same events that had already occurred, as time was infinite and the number of possible occurrences finite.[23] This observation led to a crisis for the philosopher, who believed that if past, present and future were all the same, no action taken by an individual really mattered, as any individual moment was infinitesimal in the infinity of existence. For Alma-Tadema, however, the close relationship of past and present meant that both became more relevant, rather than less. From the two, a universal aesthetic emerged, a sense of beauty that existed outside of time.

In an age of rapid technological and political change, a conception of the world in which fundamental humanity remained unchanged by the swift river of time was no doubt reassuring. For Alma-Tadema, who seems to have few strict moral or ideological motivations, the project was instead inspired more by a desire to engage with a universal, timeless aesthetic. His works repeatedly reference artworks of an earlier era, and often the subject of his pictures is an artist, artisan or art gallery. This intentional link with the bygone reinforces Alma-Tadema’s statements that true art was based on collaboration across time and space. He said:

Art is not so much the outcome of an individual brain as it is the continuity of experiences which, concentrated in one specially gifted brain, produces those incomparable artists which are the crowning features of their time and county. Art is, with literature and music, the flower of civilisation. Like civilisation, it is a development of what was done before.[24]

Alma-Tadema used memories and the physical remains of Pompeii to demonstrate that he was one of these gifted brains and that he was capable of preserving a universal aesthetic that existed outside of time.

The Sculpture Gallery was commissioned in 1874 along with a second work, The Picture Gallery (Fig. 1), by Alma-Tadema’s dealer Ernest Gambart for his own collection, rather than for sale.[25] It may seem that the originality of the artist’s work is particularly called into question here since it is extremely similar to the 1867 painting The Collector of Pictures in the Time of Augustus (Fig. 2), and an 1873 version also titled A Picture Gallery (Fig. 3). The artist himself acknowledged the difficulty in continuing to be original when the public had come to expect a certain type of work from him and was initially reluctant to complete three such similar versions of this painting, but the fact that he did allows the opportunity to better understand his creative process.[26]

These pictures are part of a core of early works dealing with the theme of the artist in Pompeii. The paintings on the wall are often copies of ancient works, many of which survived to the nineteenth century not as free-standing works of art, but as mosaics or wall paintings in the archaeological site itself.[27] The selection of works on the walls remains relatively unchanged throughout the three versions. For example, the central canvas on the rear wall of the room is drawn from a wall painting in the House of the Tragic Poet. Alma-Tadema drew inspiration for almost all the minutiae of his works from known artefacts, having built up an extensive memory of the ancient world through study. He said of the sources of such details, ‘As to the costume, mainly from sculpture and antique paintings; as to general details of architecture, furnishing, etc. mainly from museums and collections.’[28] We must then envision him in the studio, surrounded by his photographic albums and sketches from trips to Pompeii, as reported by Dolman, who once interviewed the artist in his studio.[29] Surrounded by these fragments, and at times a hired model or member of his family, Alma-Tadema harnessed these incomplete memories to imagine a complete, living world on the canvas. By pursuing the theme of the painter’s gallery, he associated himself with the body and memory of the Roman artist whose gallery was presented in the painting. Indeed, from a Victorian point of view, we might suppose that in a way, his study of archaeological materials combined his own memories with the cultural ones passed down through time, so that Alma-Tadema was the embodied revival of his Pompeian predecessor. Paralleling the physical link, this creates an aesthetic bridge between the Victorian artist and his ancient counterpart.

Almost uniquely among Alma-Tadema’s works, a small oil study on board for the later two paintings did exist, reportedly with part of the background scene of each, and was exhibited in the memorial exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1913 alongside the paintings.[30] Alma-Tadema rarely made sketches in pencil or oils for his works, and he had a reputation for conducting most of the planning and revision on the canvas itself. Helen Zimmern, one of his contemporaneous biographers, reported the following:

It is one of Tadema’s rare and precious gifts that he can see his picture finished before he has put brush to canvas. It is this gift which makes it unnecessary for him to execute the usual amount of sketching, indeed, Tadema may be said not to sketch at all; it is this that lends to his hand his rare security, and this that helps towards his precision of execution.[31]

Ethel McKenna noted the same, but did acknowledge that a great deal of overpainting was part of his working process. She wrote, ‘He never makes sketches, and could we but peel the paint in layers off each completed painting, we should find many a change of scene.’[32]

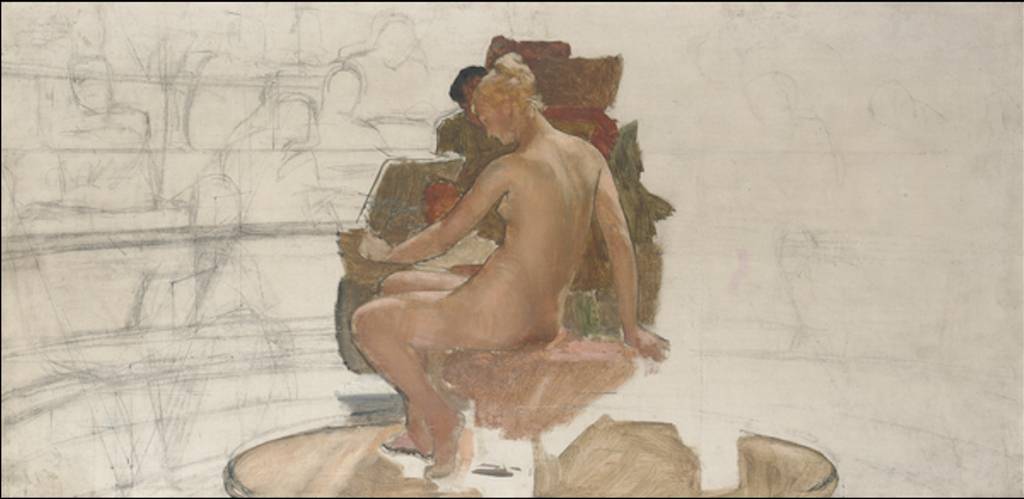

This description is enhanced by the evidence of one unfinished oil painting from 1877, The Roman Art Class (Fig. 4), which gives some indication of his working process. In the background, the architecture and placement of the figures is roughly sketched out. In the foreground, the figure of the model is the most complete, with shading detailing her shape, while the area immediately surrounding her has received a rougher treatment with some colour. Rather than the result of many independent preparatory sketches, the picture evolves on a single surface, one that is itself like the archaeological field referenced by the subject of the complete work. McKenna’s idea of peeling off layers of paint evokes ideas of excavation, gradually removing top layers to reveal a more complete picture of earlier stages of work. On this single surface, armed with knowledge of the material past, Alma-Tadema reverses the archaeological process. Out of the old and dead that had been uncovered from layers of the ground, he builds layers of paint to create something vibrant and new.

The quality of light and colour in these works was crucial to the way the artist made his paintings have an immediate connection to real, present space. The earliest of the works has the most enclosed interior view. The room is fairly dark, and while some light does seem to come in from above, there is no indication of the series of windows that appears in the later works. The doorway to the left offers little to open up the space, for although there is the suggestion of a room beyond, the path is dark and uninviting, and the succeeding room poorly lit. The light falls flat on the figures, with little shadow or contouring, and the minimal illumination on the central figures happens only through some lightening of pigment.

The treatment of light evolves significantly through the three works. In the 1873 version, a series of windows has been added, though all but one is shielded by a dark curtain. Here a warmer, glowing light emanates from the adjoining gallery. A more considered contrast can be observed, with portions of the left wall illuminated by the window above. Highlights present on the shoulder and arm of the blond woman, the raised shoulder and knee of the seated dark haired figure, and the crossed hands and gleaming scalp of the obscured older man to the far left. The most sophisticated use of light and shadow occurs in the 1874 work, with crisp light streaming in from the windows above, lending three-dimensionality to the figures and objects below. The work was particularly praised for this quality, and the artist’s contemporaries considered it one of his finest works.[33] The evolving natural quality of the light makes a case for the individuality of these three works. They are not merely copies; each is rethought by the artist. The third has the most impact on the viewer’s perception of the tangibility of history because of the vividness of the light which conveys space, warmth and life.

The three works also provide the opportunity to scrutinise how Alma-Tadema’s studio environment influenced his paintings. There is ample evidence regarding the appearance of his studios, and many reporters who covered the art world were eager to be invited into his lavish homes. His studio and paintings possessed a reciprocal relationship. One reporter noted, ‘He himself speaks of his house as a series of backgrounds to his pictures, and it is naturally in his studio especially that he has provided himself with suitable surroundings.’[34] Though the terms background and setting have different implications, this observation seems to imply is that Alma-Tadema viewed his studio as an extension of the pictorial space on the canvas. A friend of the painter mentioned that this effect was carried through the entire house, with each room apparently a reconstruction of one of his paintings.[35] While this characteristic would have been more prominent after the renovation of Townsend House in 1875 and in his later Grove End House, both of which were completed exactly to his specifications, even the earlier residences were noted for the presence of antiquities and feeling reminiscent of Pompeii.[36]

Alma-Tadema’s studio was a lively one. Rather than work in isolation, he thrived on frequent visits of fellow artists and other guests. By the time he was well established in the 1870s, Alma-Tadema and his wife were welcoming visitors twice a week, on Mondays the great and the good of society, and later in the week a circle of his more intimate friends.[37] The company of others did not spoil his ability to work, and he was happy for people to see his works as they progressed.[38] These characteristics helped blur the distinction between past and present. Never firmly located in either, both the canvas surface of the painting and the studio space itself contained features both ancient and modern. The people in the studio and the people in paint might be thought to exist between the two. The lively atmosphere of the studio had a direct impact on the canvas; it was widely thought, for example, that the figures in the later two versions of The Picture Gallery were modelled directly on Gambart and other dealers Alma-Tadema knew.[39] Thus, these living bodies in the studio become the living bodies on the canvas, echoing the roles and habits of the dead.

‘The Living Picture’: Bodies and Ruins

Bridging the mental world of memory and imagination with the physical world of space and archaeology, is that of the body, both conscious and corporeal. Modern scholars have given little attention to human figures in Alma-Tadema’s work in comparison to their lavish surroundings. When people are discussed, the tendency has been to consider them collectively, examining each figure in relation to the others as part of a project to demonstrate Alma-Tadema’s alleged preoccupation with class hierarchy or social critique. This interpretation seems to have originated with Ruskin, who criticised Alma-Tadema’s decadent vision of the past, branding him ‘The modern Republican’.[40] While talking specifically about The Sculpture Gallery, Ruskin voiced a concern that the artist’s tendency to put objects or architectural elements in the normally privileged central space of the canvas, pushing the figures to the sides, somehow challenged the normal order of society. Even Prettejohn, who takes time to challenge the idea that Alma-Tadema’s works have a particular political implication, engages with the idea of using the artist’s works as a framework for probing urban social life, both ancient and modern.[41]

Rather than mapping contemporary issues onto these images of the past, this study takes at face value, at least momentarily, that these are Romans at home in their own time and space. A focus on Alma-Tadema’s exploration of memory privileges the resuscitation or preservation of the past, rather than relocating the current age in bygone dress. Though Alma-Tadema experienced Pompeii as it was in the nineteenth century, it is significant that his elaborately imagined buildings of the past are not empty ruins, but inhabited reassemblies of a living world. This set him apart from the history painters of the eighteenth century, who were interested in the picturesque nostalgia of crumbling walls and idyllic imagined landscapes. Such works, though filled with symbolism for the viewer, had little in common with the lived experience of the past. Furthermore, unlike his own contemporaries, including Frederic Leighton, the artist’s paintings are always based on daily life, rather than on myth. Alma-Tadema’s paintings are often compared with those of the French school of néo-Grecs, particularly Jean-Léon Gérôme, but the Dutch painter took the archaeological specificity of detail and anonymity of the figures even further than his Gallic counterparts.[42] While a few of Alma-Tadema’s works have ancient textual sources, especially from the very beginning of his career, almost all can be characterised more as genre scenes than as history paintings in the traditional sense.[43]

In both The Sculpture Gallery and The Picture Gallery from the same year, the figures and how they relate to each other and the space is of particular interest. Much has been made of the domestic character of Alma-Tadema’s relationship with the ancient world, particularly in contrast with that of Leighton, who shared an interest in the classical but whose works maintain a sense of remoteness which emphasises a break between past and present. The theme of the 2017 exhibition Lawrence Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity (Leighton House Museum) was organised around this domestic emphasis, and the contrast with Leighton is highlighted specifically by Daniel Robbins. On the whole however, this continues to focus on the nature of space rather than the nature of bodies in their respective pictures.[44]

Though Alma-Tadema’s groupings of figures and theatricality of gesture belie a completely natural and spontaneous arrangement, in general his figures are not the regularlised, decorative bodies seen in the work of Albert Moore, nor the epic, heroicised bodies in Leighton, but instead are humanised in scale, posture, and relationship with each other. This is observed in The Sculpture Gallery in how the woman to the left slouches to make herself comfortable in a seated position, in how the central female figure gently rests a hand on the child’s head, and in the way the man to the right stretches forward, almost unbalanced, to reposition the large sculpture in the centre. The cool marble is still instantly suggestive of the classical world, but even this element is removed in The Picture Gallery, with only the clothes of the figures and the style of the paintings they are viewing serving as real clues to the antiquity of the subject. Here too there is an emphasis on the body of the painted figure as a natural, human one. Two central figures lean forward, straining to look more closely at the work in front of them, while behind one figure puts his hand on his companion’s shoulder, perhaps absentmindedly, as they gaze at a picture together, oblivious to the presence of a viewer gazing in turn at them. The living nature of these bodies suggests that their physicality and the emotive relationships between them create a sense of corporeal empathy between subject, artist, and viewer, indicating an understanding of the past that is not remote, but rather intimate, experienced through a shared physicality that transcends time and place.

This affective relationship with his subjects was an explicit part of Alma-Tadema’s creative process. Many of the secondary sources about Alma-Tadema frame his interest in archaeology in general and Pompeii specifically as part of an intellectual impulse to know and correctly reproduce the past. His own writing, on the other hand, reveals an emotional element as well, closing the distance created by time and scholarly study with sympathy and shared loss. A particularly revelatory letter was written to F.G. Stephens during Alma-Tadema’s visit to the site in 1878:

It is so sad to walk through the streets in which you see the ruts of the earth which passed them [Pompeii’s inhabitants] busily some 2000 years ago…Really one cannot by feel sorry for the poor people who at once lost all they cared for and of whom so many were buried alive trying to run after the first shower of pumice stone…to save themselves through the shower of ashes which [erupted?] then and in which they are found moulded from nature. They cast in one of those found last year a poor dog which died in the greatest agony to judge from the contorted position in which it was found. It was the dog belonging to the artistic friend of the house of Orpheus. Morelli the great painter has told me that once being present at the excavations they found in a cellar a skeleton of a woman and two of children. The woman was still in the position in which she tried to protect her children, leaning over them against the wall.[45]

Several elements of the letter stand out. First, that Alma-Tadema sees a close connection between the remaining walls and physical structure of the city, and the once living presence of those who built them. This reinforces the concept of the lived past that separates his work from other paintings of the ancient world, in which a ruin is empty and picturesque and history exists only on the grand scale of named events. Alma-Tadema’s artistic imagination worked to make the world present on his canvases concrete and to resurrect the lives of these people whose remains he walked among. Additionally, he was quick to insert the figure of the artist into his recollection of Pompeii, mentioning that the owner of the dog was allegedly the man who had painted the walls of the house in which he was found. This could only heighten the emotional connection, again working to bring Alma-Tadema in close proximity with the apparently distant past.

The language used by contemporary reviewers and biographers repeatedly emphasised Alma-Tadema’s ability to return life to what was previously dead. His friend Georg Ebers, remarked of the artist’s Egyptian works, ‘This is a resurrection of Egyptian life!’[46] This was high praise indeed from the famed Egyptologist, who was in a position to comment intelligently on the life of those ancient people. Another biographer, Helen Zimmern, also noted that his art succeeded at ‘resuscitating a remote historical time.’[47] She repeated the word in a comparison with the French historical painter David, remaking of Alma-Tadema, ‘He has made his ancients more living, he has resuscitated them with less visible effort; he seems to have an instinctive comprehension of antiquity.’[48] The word was used again and again by reviewers as well, with one comparing two phases of the artist’s work, noting, ‘The Egyptians resuscitations are hardly so satisfactory as the Romans’,[49] while another commented that The Picture Gallery was a ‘remarkable resuscitation of Roman times’.[50] Another said something similar when writing about the differences between some of the Victorian painters of the ancient world, noting, ‘Sir Frederic Leighton aims at presenting ideal beauty; Mr. Tadema is content to infuse life and spirit into the scenes and events of long ago.’[51] Despite the plethora of such language in nineteenth-century commentary, it has been rarely discussed in more current scholarship on Alma-Tadema. Elizabeth Prettejohn mentions the frequency of words with the prefix ‘re-‘, but only briefly touches on the significance of this observation before addressing the overall reception of the artist’s works. [52]

If we read into these words, several observations can be made. First, they further emphasise the figure’s relationship with real people who were once living.[53] By harnessing memory and imagination, Alma-Tadema has reversed a temporary death. Crucially, neither word refers to the burial that was of course a reality for the people of Pompeii; resuscitation with its medical implications and resurrection with religious ones, implying the preservation of the body, free of decay. Resuscitation in particular implies that the lapse of time between these figures’ living past and current presence in the painting is not a long one, and provides the modern viewer the opportunity to see them at a time not so distant from their own. This then, is Alma-Tadema’s role: he worked to reverse the process from flesh to stone. Even when turning back to the paintings which are more closely linked with quotidian Roman life, it is possible to see evidence of this revitalisation. The once living Romans—physically preserved only as bones and the terrible casts made from the impression of their bodies in lava—are remembered and re-humanised on the canvas.

Although he was not able to physically reverse the state of death, Alma-Tadema was able to revive the aesthetic language established by the dead Pompeiians. He made a further case for the proximity of these ancient people because by existing in a sort of symbiotic relationship with them. They provided the source material for the paintings that brought him wealth and success, while he ensured that their daily life resurfaced, making the case that they existed in reality, rather than simply in myth and literary fragments. Even reviewers who did not think Alma-Tadema’s human figures were entirely successful nonetheless often acknowledged their close bonds with modern living people. One, commenting on the men and women on the canvas, wrote that they are:

…for the most part unmistakably animals, the mere physical basis of life, which most painters suppress in order to paint either […] or passions or costumes, is almost always prominent. It is not emphasised or insisted upon, but while M. Alma Tadema’s pictures often leave us uncertain as to what the figures are thinking or feeling, they never leave us uncertain as to what they are.[54]

Reversing the usual critique that Alma-Tadema was more taken with artefacts than people, here the quality of being alive is singled out as a feature of his work. Particularly interesting in this observation is the direct reference to Thomas Huxley’s 1869 essay ‘On the Physical Basis of Life’.[55] Though the reviewer suggested that the ancient Romans were perhaps not as developmentally advanced as modern humans, what was obvious to him was that the figures on Alma-Tadema’s canvas share with contemporary man the same protoplasm, the same organic structure, that makes them alive.

It is this intervention between ruin and restoration, corpse and living body that makes Alma-Tadema’s Pompeian works particularly poignant. The artist accessed the ruins of Greece and ancient Rome largely through books, museums and photographs of artefacts. The presence of former human residents was more reassuringly distant, and it could be assumed that they died more or less in the normal passage of time. Even the tombs of Egypt, which may be considered to be inhabited, were populated only by those already dead at the time of their construction. What makes Pompeii so grotesquely compelling is that its residents, whose lives were tragically arrested, were still physically in situ, visible to visitors, including Alma-Tadema, in eerie bodily form. Alma-Tadema’s photographic collection included a picture of a skeleton, curled in agony as the person tried to escape a suffocating fate (Fig. 5). Furthermore, by the time of Alma-Tadema’s visits in the 1860s and 1870s, Fiorelli’s plaster casts were plentiful and widely known, the most chilling reminder of the humanity and suffering of Pompeii’s inhabitants.

For the artist, the relationship between past and present was reciprocal and emotionally immediate. This ability to transcend time is the ultimate motivation for Alma-Tadema’s interest in the body and mind. His study of the bodies and artefacts of Pompeii, which established his own memories of the place, culminated in paintings that blurred past and present. By suggesting that the figures in his own life and the figures in history are fundamentally the same, Alma-Tadema ensures that neither will be forgotten. It is not that the people that the artist paints are Victorians in togas, but that they are humans in togas. Ultimately, an assessment of the physiological and psychological aspects of Alma-Tadema’s work lead to the comforting assertion that while body and mind may inevitably crumble, true art can preserve beauty from the diminishing power of time.

Citations

[1]Victorians in Togas was the title for a 1973 exhibition of Alma-Tadema’s paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The idea of the ‘Victorian mirror of history’ was elaborated by A. Dwight Culler, The Victorian Mirror of History (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1985), 3–4.

[2] Simon Goldhill, Victorian Culture and Classical Antiquity (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2011). See also Norman Vance, The Victorians and Ancient Rome, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997) and Victoria G. Coates, Kenneth Lapatin, and Jon Seydl eds. The Last Days of Pompeii (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2012).

[3] See Vern G. Swanson, The biography and catalogue raisonné of the paintings of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (London: Garton & Co, 1990); Elizabeth Prettejohn and Peter Trippi, eds. Lawrence Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity (Munich, Prestel, 2016).

[4] Geoffrey Cubitt, History and Memory (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), 75.

[5] Henry Maudsley, The Physiology and Pathology of the Mind (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1872); William Carpenter, Principles of Mental Physiology (London: Henry S. King, 1874); Herbert Spencer, The Principles of Psychology (London: Longman, 1855).

[6] Maurice Halbwachs, On Collective Memory, Lewis Coser trans. and ed. (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1992; originally published as The Social Frameworks of Memory, 1952)

[7] Now in The Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, P.961.125.

[8] “The works of Laurence Alma-Tadema, R.A.”, Art Journal, March (1883), 65–68. Becker, et. al. eds., Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (New York: Rizzoli, 1997), 186, cat. 35.

[9] William Carpenter, Principles of Mental Physiology, 2nd edition (London: Henry S. King, 1875), 436–437. See also Jenny B. Taylor and Sally Shuttleworth eds., Embodied Selves: An Anthology of Psychological Texts 1830–1890 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998), 156.

[10] Carpenter, 156.

[11] Lawrence Alma-Tadema quoted in Vern G. Swanson, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema: The Painter of the Victorian Vision of the Ancient World (London: Ash & Grant, 1977), 44.

[12] Frederick Dolman, ‘Illustrated Interviews: LXVIII – Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, R.A.’, Strand Magazine, xviii, 108 (December 1899), 606.

[13] For descriptions of Alma-Tadema’s homes, Julian Treuherz, “Alma-Tadema, aesthete, architect and interior designer”, in Becker, 45–56.

[14] Dolman, 607.

[15] George Ebers, Lorenz Alma Tadema: his life and works, Mary J. Safford, trans. (New York: William S. Gottsberger, 1886), 41.

[16] Ulrich Pohlmann, ‘Alma-Tadema and photography’, in Becker, 112.

[17] Becker, 182–186, cat. 35.

[18] Swanson (1977), 47.

[19] G. A. Simcox, ‘M. Alma Tadema’, Portfolio, 5 (January 1874), 109.

[20] Henry Maudsley, The Physiology and Pathology of the Mind, (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1872), 165. First published in London: Macmillan, 1867.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Thomas Carlyle, ‘The Hero as Divinity’, in Thomas Carlyle’s Collected Works, vol. 12 (London: Chapman and Hall, 1869), 47–48. Originally published as On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History (London: Chapman and Hall, 1840).

[23] Joan Stambaugh, The Problem of Time in Nietzsche, John Humphrey, trans. (London: Associated University Press, 1987), 156.

[24] Lawrence Alma-Tadema, ‘Knowledge in Art’, British Architect (2 August 1895), 78.

[25] Becker, 186, cat. 36.

[26] Dolman, 603.

[27] Becker, 187, cat. 36.

[28] Dolman, 606.

[29] ibid, 613.

[30] Swanson, 1990, 185.

[31] Helen Zimmern, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (London: George Bell & Sons, 1902), 35.

[32] Ethel Mackenzie McKenna, ‘Alma-Tadema and his home and pictures’, McClure’s Magazine (November 1896), 39.

[33] Mentioned in ‘The works of Lawrence Alma-Tadema, R.A.’, Art Journal, March 1883, 66.

[34] McKenna, 36.

[35] Zimmern, 14.

[36] Ebers, 53–56.

[37] Frederic George Stephens, ed., Laurence Alma Tadema, R.A.: A Sketch of his life and work (London: Berlin Photographic Company, 1895), 15.

[38] McKenna, 42.

[39] Swanson (1990), 175.

[40] John Ruskin, Notes on some of the principle pictures Exhibited in the Rooms of the Royal Academy: 1875 (London: Ellis & White, 1875), 272.

[41] Elizabeth Prettejohn, ‘Lawrence Alma-Tadema and the Modern City of Ancient Rome’, The Art Bulletin, 84, 1 (March 2002) 118.

[42] John Whiteley, ‘Alma-Tadema and the néo-Grecs’ in Becker, 69–76.

[43] William R. Johnston, ‘Antiquitas Aperta: The Past Revealed’, in William R. Johnston and Jennifer Gordon Lovett, eds., Empires restored, Elysium revisited: The art of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Institute, 1991), 33.

[44] Daniel Robbins, ‘Picturing Places: Frederic Leighton and Lawrence Alma-Tadema’ in Prettejohn and Trippi, 152–3.

[45] Lawrence Alma-Tadema to F.G. Stephens, 18 April 1878, Bodleian Library, Oxford.

[46] Ebers, 65.

[47] Zimmern, 22.

[48] ibid, 39.

[49] ‘Contemporary Art—Poetic and Positive: Rossetti and Tadema, Linnell and Lawson’, Blackwoods Edinburgh Magazine, 133 (March 1883), 392.

[50] ‘The Royal Academy’, Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art, no. 37, (May 9, 1874), 592.

[51] ‘Some Charater Sketches’, Review of Reviews (May 1894), 461.

[52] Elizabeth Prettejohn, ‘”Art and “Materialism”: English critical responses to Alma-Tadema 1865–1913’ in Becker, 102.

[53] ‘M. Alma Tadema’s Picture of “Vintage”’, The Pall Mall Gazette (24 April 1871), 12.

[54] Simcox, 110–111.

[55] Thomas Huxley, ‘On the Physical Basis of life’, Fortnightly Review (February 1869) 129–145.