This article argues that the photographs of sadomasochistic play taken by surrealist artist Man Ray (1890–1976) between 1929 and 1932 reject heteropatriarchal conceptions of gender and sexuality by promoting the dissolution of the active/passive and male/female binaries. First, I introduce Man Ray’s relationship with American author and practicing sadomasochist William Seabrook and examine the potential of sadomasochistic experiences to unlock the unconscious mind. Next, I consider the ways in which Man Ray’s use of collaborative artistic practices and his focus on the subjective experience of the masochist contribute to the fluidity and mutuality of sadomasochistic power dynamics. I also discuss the role that women played in the creation and staging of these images, including American photographer Lee Miller, who was also Man Ray’s photographic assistant during this period. Finally, I examine a lesser-known series by Man Ray entitled Fetishistic Mise-en-scène for William Seabrook and consider the function of simulation in scenes of erotic violence as well as the economic and political implications of depicting non-reproductive sexual behaviours in interwar France.

Man Ray’s 1930 Homage to D.A.F. de Sade seems, at first glance, to epitomize the surrealist fascination with Sadean sexuality as well as the group’s apparent misogyny. Published in the second issue of the periodical Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution, the photograph depicts what amounts to a macabre still life: an apparently disembodied female head is perched on a book and covered by a clear bell jar. A thin piece of fabric rests over the woman’s closed eyes, and her face is tilted upwards with her lips parted slightly to reveal her two front teeth. The unconscious – or even lifeless – expression, the apparent decapitation of the female body, and the title’s reference to the controversial Marquis de Sade have been read by some scholars as exemplifying the surrealist fascination with the aestheticisation of violence toward women.[1]

Yet, this same symbolism was appropriated by Lee Miller, Man Ray’s photographic assistant at the time, in her 1930 Tanja Ramm with Bell Jar, Variant on Homage to D.A.F de Sade. Almost identical in subject matter to Man Ray’s Homage to D.A.F. de Sade, Miller’s photograph features the same pale woman – this time identified in the work’s title as Tanja Ramm, Miller’s roommate and a frequent photographic subject of Man Ray – with her head once again apparently decapitated and placed under a glass bell jar like a scientific specimen. In contrast to Man Ray’s version, Miller’s photograph depicts Ramm facing the viewer directly, and there is no band of material covering her eyes. Ramm’s frontal positioning and the inclusion of the subject’s name in the title counter the tendency in Man Ray’s image toward objectification and has, therefore, been read by Katherine Conley as a proto-feminist interpretation of the sadistic symbolism.[2]

Aside from these small changes, however, the image’s overall subject matter remains identical to Man Ray’s Homage to D.A.F. de Sade. Miller’s photograph celebrates the same sadistic impulse that, for some art historians and critics, colours much of Man Ray’s work with misogynistic undertones.[3] This fascination with the relationship between eroticism and violence – and, more specifically, with sadomasochism – permeated both the Bretonian and the Batalliean factions of Parisian surrealism.[4] The artists and writers involved in such groups attempted to examine the relationship between eroticism and violence through creative processes, such as automatic writing and dream analysis, that revealed the desires and thoughts of the unconscious mind. This fascination with unconscious desire was realized, at least in part, through the creation of erotic imagery, much of which had a pronounced interest in depicting non-normative sexualities and sexual behaviours.

The visualization of these so-called perversions was intended to both shock the public (ideally into reconsidering their bourgeois conceptions of morality and social norms) and serve as a means of capturing the unbridled sexual energy – what Freud called the libido – of the unconscious mind.[5] The surrealists recognized that, in order to critique bourgeois conceptions of sexual behaviours and sexuality, it was necessary to undermine their foundations, whether the primacy of sexual reproduction over sexual pleasure or traditional, binary gender roles.[6] The surrealists, therefore, advocated for the development of a radical new sexual discourse that held pleasure, rather than reproductive, economic, or political concerns, to be the ultimate goal of sexual practices.

The practice of sadomasochism is defined by the sexualization of pain and humiliation – both in terms of inflicting pain and humiliation upon others, or sadism, and having pain and humiliation inflicted upon oneself, or masochism. Some scholars have attempted to separate sadomasochism into its two component parts, sadism and masochism, transforming it into a binary that superimposes neatly upon heteropatriarchal conceptions of sex, in which sadism aligns with the active, male role and masochism with that of the passive, female counterpart.[7] From this perspective, Man Ray’s interest in photographing women in the role of the masochist can appear to be additional evidence of surrealist misogyny. Instead, I argue that Man Ray’s fascination with sadomasochism must be understood in much more nuanced terms.

The gendered separation, evoked above, of sadism and masochism was in fact widely questioned by popular sexology theories and texts from the period. For Freud, whose theories on the unconscious mind had a considerable influence on the surrealist movement, ‘…the most remarkable feature of this perversion [sadomasochism] is that its active and passive forms are habitually found to occur together in the same individual’.[8] This suggests the potential for an inversion of position – and, therefore, of power – revealing the highly complementary and mutualistic nature of sadomasochistic relationships. Through their ability to change roles sadomasochists put traditional conceptions of gender and sexuality – which view power imbalances as highly gendered and inflexible – into question.

Man Ray’s work serves as an ideal point of entry into the surrealist fascination with perverse forms of erotic desire and their potential to radically subvert bourgeois norms. His photographs span both the subtly erotic and the overtly pornographic categories of surrealist art, and his tendency to involve women he knew personally in his work, both as models and as photographic assistants, allows for a fuller understanding of the surrealist interest in the erotic from both male and female perspectives. In this article, I will counter the traditional feminist view that images of masochistic women must reflect the inherent misogyny of their creators, as well as the internalized misogyny of the women who choose to participate in such activities.

The article is divided into three main sections. The first introduces American author and practicing sadomasochist William ‘Willie’ Seabrook and discusses his involvement in the production of Man Ray’s sadomasochistic imagery. I then discuss the ways such imagery can be read as a continuation of the surrealist desire to delve into the unconscious mind. The second section considers the function that the subjective experience of the masochist and collaboration play in Man Ray’s images of bondage. I discuss the crucial role that women played in the creation of these images, focusing on the involvement of Miller, Marjorie Worthington, and the semi-anonymous Justine. The third section of this article deals with a set of images that have received little critical attention since they were first released in 1994: the Fetishistic Mise-en-scène for Willian Seabrook series. I consider how simulation and same-sex desire function to destabilize traditional power structures within these scenes of lesbian sadomasochistic play.

In considering the roles that collaborative creative processes, the subjective experience of the masochist, simulation, and same-sex sexual activity play in these images, this article offers an alternative means of engaging with Man Ray’s images of bondage; an engagement that centres on the experience of the women depicted in these images – rather than an engagement that focuses on the experience of the photographer/viewer. The traditional feminist focus on the implications of erotic or pornographic photographs or films on women in general should be replaced with a consideration of the impact of the creation of such imagery on the specific women involved in its production. The radical views of anti-pornography feminists such as Angela Dworkin should be acknowledged, but to claim that all erotic imagery is harmful to all women (especially works that depict sexual violence, that most abhorrent of erotic categories) completely disregards the sexual and artistic agency of the women who choose to be involved in the production of such works.[9]

Mysticism and the Unconscious

Seabrook was a key collaborator on many of Man Ray’s images of bondage and the creator of his own sadomasochistic photographs, some of which were published and widely circulated in periodicals and shared among the surrealist group’s members. Attributed to Seabrook and dated to 1930, a set of three images of masked and collared subjects appeared in the fifteenth issue of Georges Bataille’s journal Documents.[10] The figures depicted in the Documents series are cropped just under the shoulders, fragmenting their bodies and making their faces the focal point of the photographs. This focal point then becomes the site of the images’ erotic charge, as well as the site of the dissolution of the conscious self through the ecstatic experience of sadomasochistic play. The images’ foregrounding of an eroticized, masked subject (which was reinforced by an accompanying text entitled ‘The “Capuut Mortem” or the Alchemist’s Wife’ by Michel Leiris) suggests a crucial aspect of sadomasochism’s allure: the potential to invoke mystical experiences.[11]

In two of the images – Seabrook, Justine in Mask (1930, Fig. 1) and Leather Mask and Collar – the subjects’ heads and faces are tilted back and upward in a position that recalls images of individuals experiencing sexual – or religious – ecstasy.[12] The mystical or religious potential of sadomasochistic play was central to Seabrook’s interest in such practices.[13] In Seabrook’s 1940 book Witchcraft: Its Power in the World Today, he discussed his sadomasochistic experiments with a woman he calls Justine – after the novel by the Marquis de Sade.[14] This woman, the same woman depicted in the Documents series, participated in a number of sensory deprivation activities intended to enhance her extra-sensory perception.[15] She helped Seabrook to design a leather mask that would dull her senses in order to increase her chances of achieving a mystical state of precognition. According to Seabrook, the mask:

…covered Justine’s entire head, following all the contours of her face and, when laced tight in the back, fitted smoothly and tightly as her own skin. The only opening was a slit for the mouth, which followed the lines of her lips, and through which she soon learned to breathe, deeply and steadily.[16]

The mask was designed to dull not only her senses of sight and hearing, but also her sense of smell and her ability to detect movement in the space around her, creating the ideal condition for Justine to experience mystical visions. It was not just Seabrook who gained pleasure from the act of masking; Justine herself advocated for the creation of such a mask and helped Seabrook to design it in order to optimize her chances of achieving this highly desired state of extrasensory perception.[17]

The erotic and mystical potential of ‘…the simple fact of masking – or negating – a face’ was further explored in Leiris’s accompanying text.[18] Leiris compares the erotic potential of the act of masking to the religious fetishization of relic objects.[19] For Leiris, the erotic fetish of the mask and the religious fetish of the cult object rely on the ‘…same mode of magic thought, such that the part is taken for the whole, the accessory for the person, so that the part is not only equal to the whole, but even stronger than the whole…’.[20] Through this substitution of a part (the mask) for a whole (Justine’s body and identity), the masked individual undergoes the dual processes of fetishisation and depersonalisation, processes that transform the previously identifiable person into a foreign object of desire.[21] This act of masking, through its promotion of sensory deprivation, also transforms the masked figure’s reality from a comprehensible arrangement of sensory inputs into the total absence of all sensation.

This interest in pushing the boundaries of human perception through extreme psychological and/or physiological experiences can be linked directly to surrealism’s celebration and prioritisation of the desires and thoughts of the unconscious mind over those of the conscious self.[22] This conception of the unconscious was rooted in late nineteenth century dynamic psychiatry, as developed by Jean-Martin Charcot and Pierre Janet.[23] These images of masked figures, therefore, can be read in terms of the surrealist interest in freeing the subconscious from the constraints of normal sensory perception, allowing abilities, thoughts, and desires that were usually repressed by the conscious mind to rise to the surface.[24] Given their relevance to these surrealist preoccupations, it is not surprising that Seabrook’s images attracted the attention of a number of surrealists, including Man Ray.[25]

Man Ray’s 1930 Gloved Figure exemplifies the relationship between sadomasochism and mysticism (Fig. 2). The photograph features a figure clad in a polished silver collar, suede elbow-length gloves, and a matching suede mask. The mask and gloves have been carefully constructed out of the same light-coloured suede material and appear to fit snugly over the model’s face and hands, suggesting that they were made specifically for this shoot based on the model’s exact measurements. The model’s hands are pulled above their head and are attached to a metal chain hanging from the ceiling with a pair of handcuffs. The model is clearly in the masochistic position, their sense of sight and hearing deprived by the mask and their ability to move severely, if not completely, hindered by the handcuffs and chain, which leaves them seemingly suspended from the ceiling.

The image is cropped, revealing only the top part of the model’s body. This fragmentation of the body is typical of surrealist depictions of the human figure – as demonstrated by the masked figures in the Documents series. This fracturing of the human body has been read by some art historians as evidence of the movement’s desire to inflict physical and psychological violence upon others, especially female others.[26] I propose that the cropping should be read not as evidence of Man Ray’s rather literal desire to chop his model up, but as a means of inserting gender ambiguity into the photograph. According to Tirza True Latimer, ‘for Man Ray, dada/surrealism’s unofficial court photographer, gender ambiguity was an important focus of visual investigation’.[27] Any stereotypically gendered characteristics have been purposefully removed from the image, either through the process of cropping or the act of masking the model.

This bodily ambiguity is also present in the model’s positioning, as the cropping leaves the viewer unsure of whether the figure is resting comfortably on the ground or if they have been forced into a more uncomfortable position by the same sadist who masked and bound them. Man Ray’s use of cropping enhances the photograph’s performative depiction of sadomasochism, framing the model in a way that prevents the viewer from seeing the full scene and, therefore, the full impact such play has on the model’s body. The fact that the model’s shoulders are relaxed and resting below their chin makes it highly unlikely that they are actually suspended from the ceiling. Instead, they appear to be simply standing, their feet firmly planted on the ground. The figure’s neck is long, their head positioning regal and upright, and their face confronts the viewer directly from behind the mask. The cuffs are loose around their wrists and their hands lightly grasp the chain to which they are supposedly bound. The ambiguity of the figure’s position functions as a depersonalizing force in the photograph, further removing the viewer’s ability to identify the model, their gender, and their position in the active/passive binary. The contrast between the initial impression of a faceless woman, bound and helpless before the sadistic photographer/viewer, and the reality of the ambiguously gendered figure, comfortably standing on the ground and confidently looking out at (or perhaps through) the photographer/viewer from behind the mask as they attempt to reach a mystical state of precognition, disrupts the traditional binaries on which heteropatriarchal sexual norms rest – that of the weak and passive female succumbing to the advances of the strong and active male.

As discussed above in reference to the Documents series, the process of masking can be read as a means of detaching the subjective self from the body – and, therefore, one’s assigned gender – in order to transform a person into a fetish object that could then be used as a channel for mystical experiences. This same fascination with extreme physiological and psychological experiences is illustrated in Gloved Figure, both through the previously discussed act of masking and through the mystical technique of ‘dervish dangling.’[28] This technique, discussed by Seabrook in his Witchcraft in the World Today, involved hanging a person by one or both of their wrists as a means of pushing their body to physiological extremes in order to bring on a state of extrasensory perception.[29] Leiris also discusses the associations between dervish rituals and mystical visions in his essay ‘“The Caput Mortuum” or the Alchemist’s Wife’. This interest in stimulating mystical experiences through acts of psychological or physiological discomfort is central to the photographs discussed in this section. Without the promise of precognition and the hope of freeing the unconscious mind from the constraints of consciousness, these photographs of sadomasochistic play would not exist.

Creative Collaboration and the Subjective Experience of the Masochist

One of the series Seabrook and Man Ray collaborated on – and the only one in which Seabrook actually modelled – is Man Ray’s Lee Miller in Collar, dated to between 1929 and 1932 (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4).[30] In this series, Miller models one of the collars Seabrook designed for his and Man Ray’s photographic collaborations. Miller’s identification with the masochist, through her donning of the collar and her visual relegation to the photographs’ bottom register, seems to exemplify patriarchal violence toward women. However, on further examination, this apparently blatant display of misogyny is undermined by the series’ focus on Miller’s subjective experience and her role in staging the scenes.

Miller is the central subject of the series, her face the focal point of each photograph. While Seabrook’s hunched pose and somewhat dour expression change only minimally from one image to the next, Miller’s expression and pose differ dramatically in each photograph. It is thus Miller who determines whether the photograph will be read as a humorous game of dress-up or as an erotically charged depiction of sadomasochistic play, and it is her subjective experience that is the photographer’s – and the viewer’s – focus. While Seabrook fades into the background in his nondescript sweater, Miller’s elegant features are accentuated by both the collar and the careful backlighting. A halo of light encircles her face, while her carefully controlled poses mimic those of her early days as a fashion model – as well as the many less controversial portraits Man Ray took of her.[31] What seems, at first glance, to be evidence of Seabrook’s dominance of Miller – the collar and his firm grasp upon it – is what pulls the viewer’s attention toward Miller’s face, emphasizing her expression and identity and, subsequently, her subjective experience.

Man Ray’s fascination with the subjective experience of the masochist in his photographs parallels Sade’s tendency to focus on the experience of the masochistic victims in his writings. Sade, along with masochism’s namesake, Austrian author Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, utilized erotic power structures in his novels to explore non-normative means of liberation, desire, and pleasure – concerns shared by much of Man Ray’s interwar photography.[32] Scholars such as Neil Cox and David Bate have written at length on the surrealist preoccupation with Sadean conceptions of sexuality.[33] For the surrealists, Sade was the embodiment of the idea of liberating sexual desire from the constraints imposed by society, and they looked to Sade’s novels and philosophical texts for insight into their own conceptions of desire.[34]

Sade’s focus on the subjective experience of the victim – and not that of the victimizer – in his works is central to my reading of Sadean sexuality as capable of destabilizing existing power structures. According to Bataille, ‘in complete contrast to the torturer’s hypocritical utterances, de Sade’s language is that of a victim.’[35] The torturer, the pure sadist, relies on the ‘language of the authority’ in order to provide a justification for his actions, while the victim, the masochist, speaks out against such authority by describing the violence enacted on him.[36] This paradox reveals the ambiguity inherent in Sade’s writings. Though they seem, at first glance, to fetishize misogyny and violence toward women, on further examination their political message – and literary value – derives from the fact that they present a more complicated power dynamic. Like Sade’s writing, Man Ray’s images of female masochists do not simply reinforce patriarchal norms of violence and misogyny. Instead, they complicate such norms through consensual – or contractual – simulation that rejects the active male/passive female binaries.

In one of the photographs, Seabrook is captured as he yanks the collar back, pulling Miller’s head back with it (Fig. 3). Seabrook’s face is slightly blurred, emphasizing his movement and, subsequently, his identity as the sadist. This blurring also softens his expression, drawing the viewer’s eye away from his face and toward Miller’s sharp, light-drenched features. Miller retains her sexual agency in the scene, making direct eye contact with Seabrook and maintaining a relaxed pose. Her mouth is closed, and a hint of a smile plays around the edges of her lips. She does not resist Seabrook’s movement, her chest and shoulders are squared and upright, while her arms rest calmly at her side. She is depicted as an active participant in the scene, a scene that (as both a photographer herself and as Man Ray’s photographic assistant) she had a role in staging.

In another image from the series, Miller is depicted in a relaxed pose with her eyes closed and her mouth open in an expression of erotic enjoyment (Fig. 4). Seabrook is once again looking down at Miller, but, in this image, she does not look back. She remains upright, but her body positioning is relaxed. Though she is no longer the alert and controlled figure she was in the previous photograph, Miller continues to retain her agency as an active participant in the scene, this time as someone who is receiving pleasure from playing the role of the masochist. In playing the role of the masochist while simultaneously retaining her sexual – and personal – agency, Miller echoes and subverts, rather than reproduces, the structural patriarchal power imbalances that produce disempowered female subjects.

The series’ focus on Miller also points to the crucial role she played in Man Ray’s life, as model, muse, lover, and photographic assistant.[37] Man Ray’s emphasis on Miller’s subjective experience demonstrates not only his own immense fascination with her and the intense nature of their tumultuous relationship, but also her autonomy and agency within that relationship. In addition to the important role Miller played in Man Ray’s photographic production, she was an established photographer and artist in her own right: Miller opened a studio at 12 rue Victor Considérant in 1930 seven months after beginning her initial apprenticeship with Man Ray as assistant and model.[38] Miller rejected the identity of muse, as well as the traditional constraints of heterosexual monogamy, insisting on maintaining multiple romantic and sexual relationships and continually travelling throughout her and Man Ray’s four-year romance – much to Man Ray’s chagrin. Miller should, therefore, not be viewed as a passive bystander in the production of this series, but as an important artistic collaborator and close friend of both Man Ray and Seabrook.[39]

The use of custom-made props also emphasizes the collaborative nature of these images. The photographs from this series are likely documentation of Miller testing the fit and comfort of the collar, specifically in terms of the prop’s ability to be used in sadomasochistic play. Man Ray’s tendency to commission custom-made props for his photographs is well documented in both his own autobiographical writings and in letters sent between him and Seabrook. In his autobiography, Man Ray describes in detail the conception and execution of a silver collar designed by Seabrook for Worthington, a collar Man Ray used in later photographs. The collar was designed to limit the wearer’s movement by restraining the ability to turn one’s head or swallow. According to Man Ray, the collar was fabricated by a silversmith based on Worthington’s exact measurements, and consisted of ‘…two hinged pieces of dull silver studded with shiny knobs, that snapped into place, giving the wearer a very regal appearance’.[40] This comment suggests the power that Man Ray attributed to the collar’s masochistic wearer.

In an undated letter from Seabrook to Man Ray, Seabrook described in detail a number of props he wanted Man Ray to commission, presumably as part of a photographic project the two were working on together. The props mentioned in the letter include

[a] black priest’s robe…, [a] priest’s shovel hat…, [a] wasp-waist hour-glass corset finished either in some glittering fabric that looks likes polished steel, or in black leather-like material to match the mask…, boots or slippers with fantastically high heels….[41]

Such texts reveal the extent to which the costumes seen in Man Ray’s photographs of sadomasochistic play were designed and constructed with an immense attention to detail, enhancing both the performative quality of the images and the sense of intimacy between model and photographer. In order for these custom-made props to be fabricated, the models must have been willing to meet with both Man Ray and Seabrook on numerous occasions, allowing the men to take their measurements and then trying on the finished costumes to ensure that they were wearable. The intimate nature of the fabrication process is enhanced by Man Ray’s and Seabrook’s tendency to involve models they knew personally in their work.

The Lee Miller in Collar series’ focus on the masochist’s subjective experience and reliance upon highly collaborative creative processes complicate the traditional feminist narrative that images of female bondage are inherently misogynistic and fetishize violence against women. All three of the women discussed above – Justine, Miller, and Worthington – maintained long-term professional and personal relationships with either Man Ray or Seabrook. Furthermore, Miller, as Man Ray’s photographic assistant from 1929 to 1932, was involved in the production of all of his photographs depicting sadomasochistic play.[42] The central role these women played in the creation of these images – as models, assistants, and collaborators – exemplifies the highly reciprocal nature of sadomasochistic relationships, and, more specifically, Man Ray’s photographs of sadomasochistic play.

Simulation and Same-Sex Desire

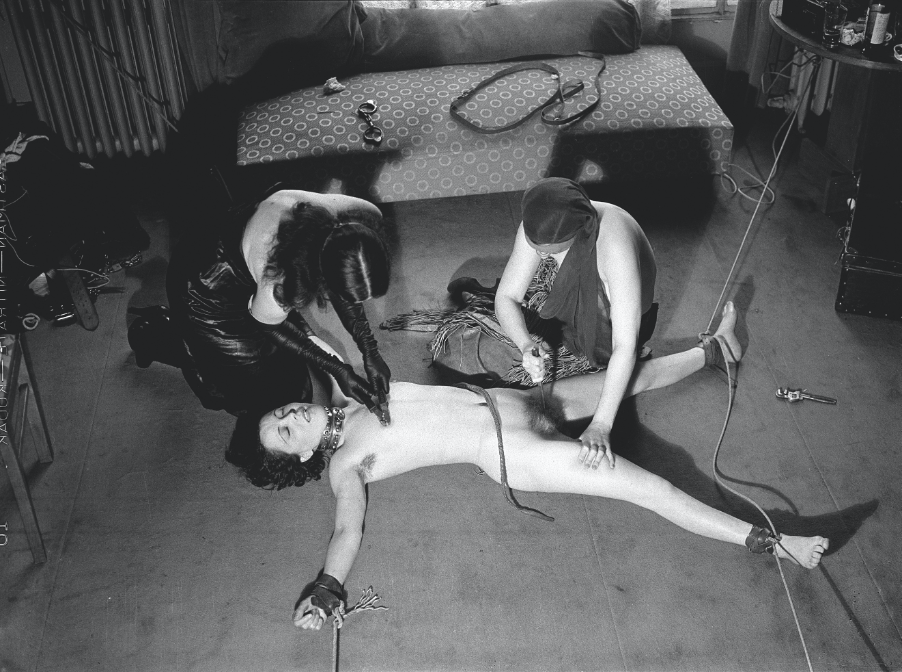

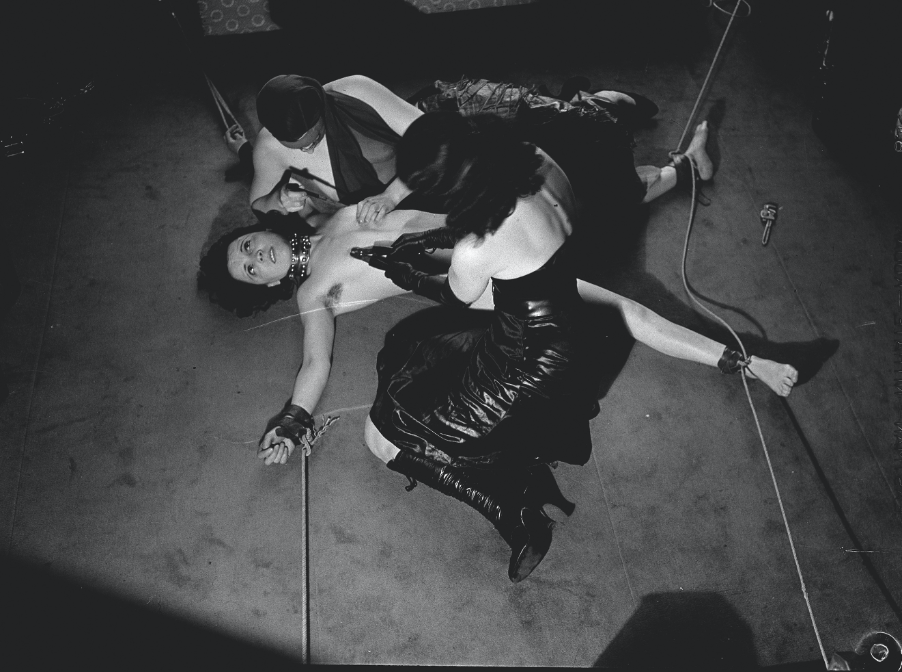

Created in 1930, the Fetishistic Mise-en-scène for William Seabrook series was considered so perverse it was only widely released to the public in 1994 (Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7 and Fig. 8).[43] As the title suggests, the series was created by Man Ray at the request of Seabrook.[44] The fact that these images were not released to the public when they were taken, coupled with the fact that the majority of the images exist only as negatives, has resulted in little scholarly attention on this series. Additionally, the Musée national d’art moderne holds little information in terms of the series’ provenance and does not keep object files for photographic negatives.[45] While the actual nature of such patronage is unclear from the current scholarship available on the negatives, Seabrook’s involvement in the images’ staging and creation is evident and – coupled with Man Ray’s identity as the photographer – brings issues of male voyeurism and the fetishization of lesbianism for male pleasure to the fore. While these issues certainly problematize this series – in the same way that issues of male voyeurism and the fetishization of lesbianism for male pleasure problematizes the larger tradition of pornography – I argue that these images can still be read against the grain as destabilizing heteropatriarchal norms through their reliance on simulation and their depiction of same-sex sadomasochistic activity.[46]

In the images that exist as pairs – six of the nine negatives make up these pairs – the scenes’ reliance on simulation becomes evident to the viewer. These pairs are variations on the same scene, with similar costuming, posing, and staging (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6; Fig. 7 and Fig. 8). The primary difference between these paired scenes is the masochist’s facial expression and pose. These paired images from the Fetishistic Mise-en-scène for William Seabrook series reveal the extent to which sadomasochistic play – whether real or staged – is always a simulation.[47] The very language of sadomasochistic communities – play, scene, role, actor – references the world of theatre and indicates the highly performative character of sadomasochism.[48] It is the simulation of patriarchal (or dominant) power structures for the purpose of sexual pleasure that defines sadomasochistic relationships. In temporarily taking up the role of a sadist or masochist, individuals who participate in sadomasochistic play put into question the usually involuntary assignation of such power roles based on gender identity.

The first pair of negatives features the sadist clamping one of the masochist’s nipples as she bends over the masochist. The masochist wears the black collar and bondage device as she lies on the ground in a foetal position. In both versions of the scene, the sadist and the masochist remain in the exact same pose. In one version, though, the masochist’s eyes are open, and she is staring directly ahead at something just outside the edge of the photograph. Her expression is completely indifferent, there is no acknowledgement of pain nor pleasure in her face. The contrast between the masochist’s face in the first version of this scene – an expression of sexual gratification – and her expression in the second version of this scene – an expression of complete indifference – demonstrates the crucial function that performance plays in both pornography and sadomasochistic play. Without an emotive expression on the face of the masochist, the sadomasochistic allure of the images evaporates. With her eyes open and her face expressionless the implication that the submissive figure is actually serving as the willing victim of the sadists is lost, and the sense of eroticism that the images are designed to impart on the viewer disappears.

The second set of negatives features three women: two sadists and one masochist (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6). The first version of the scene is perhaps the most unsettling image in the series (Fig. 5). The masochist lies in a spread-eagle position, her arms and legs bound in leather cuffs and tied to the furniture with pieces of rope. The sadists bend over her, the dominatrix figure – the sadist dressed entirely in black leather – clamping the masochist’s nipple with what appears to be a pair of pliers, while the other sadist grasps the masochist’s right leg with one hand and positions a knife over her mons pubis, as if ready to plunge it into her flesh. The extreme violence of the sadists’ acts is contrasted with the masochist’s relaxed pose and expression of apparent sexual pleasure. Her eyes are closed and her mouth is open. She does not strain against the ropes that hold her down.

The second version of the scene depicts the masochist in the same pose, with the dominatrix on the opposite side of the masochist, still with the pliers in hand, while the other sadist leans back, the same knife now pressed against the masochist’s left breast (Fig. 6). This shift in the positions and actions of the sadists are matched by a shift in the expression of the masochist. Her eyes are wide open and her mouth is slightly ajar as she gazes up at an invisible presence outside the frame of the photograph. Her previous expression of sexual enjoyment has morphed into one of concentration. She does not struggle against her restraints, but this physical acceptance of her situation is juxtaposed with an expression of mental concentration, her eyebrows raised as if she is listening to off-stage directions.

The third pair of negatives features only the masochist (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8). She is nude except for the silver collar, and her hands are cuffed behind her and attached to a rope that is strung over a curtain rod to create a makeshift pulley-system. In the first image, the rope is pulled taught (Fig. 7). The masochist’s heels are pulled off the ground and there is tension in her shoulders and stomach. Her face and hair are slightly blurred, emphasizing the sense of movement in the photograph and the tenuous nature of her position. Her face is partly shrouded by her hair, but her expression appears to be concentrated on the scene. She is vulnerable, both to the desires of the sadists and the gaze of the photographer and viewer.

In the second image of this scene, this sense of vulnerability is transformed as the carefully constructed simulation is revealed to the viewer (Fig. 8). The tension in the rope has been reduced. The masochist’s feet are firmly planted on the ground, and there is no longer any visible strain in her shoulders and stomach. She remains handcuffed and tied to the rope, but the discomfort imparted by the previous photograph has been reduced through the releasing of the rope and the planting of the masochist’s feet on the ground. The masochist’s face also undergoes a dramatic transformation. The serious expression of concentration has transformed into a wide smile as the figure lifts her face up. She appears to be laughing, both at the absurdity of the situation in which she has found herself and at the seriousness of the previous scene(s). The change in positioning and facial expression from the first negative to the second imparts a sense of subjective individuality onto the masochistic figure that brings the simulation to the forefront of the viewer’s experience of the image.

The crucial function of the theatrical – or simulative – aspects of sadomasochistic play is exemplified by contemporary critiques of both sadomasochism and pornography. According to Linda Williams, ‘…a problem arises when we consider the difference between actual abusive sexual practices and their representation in pornographic fantasy’.[49] Equating fantasies of sexual violence – and their consensual acting out in the form of sadomasochistic play – with non-consensual acts of violence ignores the crucial function of simulation and mutuality in such fantasies. For Williams, ‘the trouble is that existing power relations between the sexes are inextricably tied both to our fantasies and to expressions and enactments of sexual pleasure’.[50] The idea that those being oppressed can gain pleasure from acts that simulate the most violent and visceral forms of such oppression – through the participation in a fantasy in which such power structures are deconstructed – renders bourgeois conceptions of pleasure and power ineffective. By condemning individuals who engage in the simulation of power structures for sexual pleasure, traditional analyses of such images ignore the subversive potential of such stagings, as well as the potential of such experiences to help heal the trauma inflicted by the same power imbalances such play simulates.[51]

In depicting explicit scenes of sadomasochistic play, often involving two or three participants (as opposed to foregrounding a single masochist, which leaves the photographer or viewer to take on the implied role of the sadist), these negatives go beyond the erotic to address sexuality more directly. This interest in sexuality is also exemplified in the images’ focus on non-reproductive sexualities and sexual practices. None of the images in the Fetishistic Mise-en-scène for William Seabrook series depict procreative sexual acts. Instead, the series features sexual acts whose only function is pleasure – whether it be the pleasure of the sadists, the masochist, or simply Seabrook himself. Additionally, in depicting sexual behaviours – sadomasochism and lesbianism – which are non-reproductive in nature, the practices promoted in these images are unable to serve a capitalist system-sustaining function. According to Foucault, the West’s interest in regulating sexuality is ‘motivated by one basic concern: to ensure population, to reproduce labour capacity, to perpetuate the form of social relations: in short, to constitute a sexuality that is economically useful and politically conservative…’.[52] By promoting sexual activities that reject the capitalist desire for an ever-increasing population and, subsequently, workforce, these images actively disrupt bourgeois conceptions of sexuality and sexual behaviours.

This interest in non-reproductive sexuality is found throughout surrealist discourse on sexuality, most famously in the twelve research sessions on sexuality recorded, transcribed, and later published in the eleventh issue of La révolution surréaliste.[53] In these sessions, members of the group discussed frankly and in great detail their sexual experiences, preferences, and viewpoints – many of which advocated for sexual acts, such as sodomy, that rejected the pronatalist viewpoint espoused by the French church and state. The decision, then, to depict both lesbianism and sadomasochism in this series rejects both the sexual norms imposed by mainstream French society at the time and the norms imposed by the more conservative members of the surrealist group, including those of André Breton, the movement’s self-proclaimed patriarch.[54]

Both male and female homosexuality were discussed in the research sessions, although the participants’ views on such matters were polarized.[55] Female homosexuality was more acceptable to the session participants than male homosexuality, exemplifying the (predominantly male) tendency toward the fetishization of lesbianism and the societal fear of ‘lesbians who want to play a male role’.[56] This distinction between ‘lesbians who remain women’ and lesbians who ‘play a male role’ serves as an alternative conception of the active male/passive female binary, in which the male (or active) lesbian is viewed as more perverse, an instigator and a sexual aggressor, while the female (or passive) lesbian is viewed as continuing to conform to heteropatriarchal expectations of femininity.[57] In contrast to the more acceptable passive, feminine lesbianism fetishized in the research sessions, the Fetishistic Mise-en-scène for William Seabrook series depicts same-sex desire as simultaneously feminine and active.

Though a woman still takes on the role of the masochist (whose perceived victimhood has already been put into question), she is at the mercy of not one but two active female instigators. The central female sadist is clad entirely in black with her breasts exposed and presents a visual antithesis to the naked and bound masochistic figure (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6). Her knee-high lace-up boots, elbow-length gloves, headscarf, mask, and wasp-waist corset – all made entirely of shiny, black leather – give her the appearance of a dominatrix and follow the conventional aesthetics of sadomasochistic play (an aesthetic that has not changed much in the ninety years since these photographs were taken). Except for the three images in which the masochist is depicted alone, this dominatrix figure stands or sits above the submissive female. Her placement puts her physically above the masochist, suggesting her physical prowess and giving her the power – both physically and psychologically – to enforce her will on the masochist.

The second female figure – who appears only in one scene – is dressed in a much more delicate fashion (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6). She wears a light-coloured headscarf and long, billowing skirt. The headscarf serves as a sign of modesty, covering the woman’s hair and breasts. The only sartorial indication of her engagement with sexually deviant behaviour is her bare back. The woman’s overt femininity is also visible in the positioning of her body. In one of the negatives, she lies back, resting on her right forearm, her ankles daintily crossed in a way that accentuates her simple black heels (Fig. 6). Her position recalls that of traditional Venus figures, the epitome of feminine beauty and grace. Her inclusion in the series seems to advocate for feminine participation in transgressive sexual acts that ignore the precepts of bourgeois morality. The juxtaposition between the woman’s hyperfeminine costuming and posing and her sadistic behaviour rejects the equation of femininity with passivity; a juxtaposition that is even more striking given that it is this delicate, feminine sadist who perpetuates what is perhaps the most grotesquely violent act in the series, the apparent plunging of a knife into the mons pubis of the masochist.

The difference in costuming between the two female sadists reads as a visual representation of the range of possible female sexual identities and preferences. In depicting only women in the role of the sadist, the Fetishistic Mise-en-scène for William Seabrook series provides an alternative conception of female sexuality that is not confined to the traditional active male/passive female binaries. Forced to choose between either the castrative seductress or the passive victim, the women in this series refuse to embody either. Donning the visual attributes of such archetypes while simultaneously engaging in not one but two perversions, the sadists evoke but ultimately destabilize the dominant heteropatriarchal narrative of female sexuality as inherently passive and masochistic.

Conclusion

Man Ray’s images of bondage destabilize the traditional active male/passive female binary through their reliance on collaborative creative processes, their focus on the subjective experience of the masochist, their foregrounding of simulation, and their depiction of same-sex sexual activity. By offering a more nuanced perspective on an often-overlooked aspect of Man Ray’s œuvre, this article provides an alternative to the traditional condemnation of sadomasochism – and surrealist depictions of it – as inherently misogynistic. The concerns addressed in this article resonate in contemporary debates about sadomasochism and patriarchal power dynamics, as well as the role that heteropatriarchal norms play in the formation of societal expectations of female sexuality. The correlation of violent sexual desires with actual acts of misogynistic violence ignores the subversive potential of sadomasochistic fantasies, fantasies that rely upon the performative staging – and, therefore, disruption – of patriarchal power roles and gender norms.

Appendix A

Fonds Man Ray, MANR6, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France.

Michel Leiris has my best mask negatives, in Paris – including the one about which you enquire and some better ones – with exclusive permission to publish a choice of them in Documents. He has written that they, or some of them, will appear in an early issue. If Surréaliste magazines are like most magazines Aragon will doubtless regard the matter as consequently ‘out’ for his projected publication. If, however, he is still interested, I hereby authorize Aragon to publish any mask pictures which Leiris may be willing to release to him. But the release, you understand, depends entirely on Leiris. This authorizes you to treat directly with him. If Aragon should publish, please ask him to credit both the mask and the photograph to me, as Documents has agreed to do with those it publishes’.

Correspondence from William Seabrook to Man Ray, 22 August 1930, MANR6, Fonds Man Ray, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France.

‘Flying to Timbuctoo – and very much want to see you before leaving. Forgive short notice. But could you either lunch with me just now, Restaurant de l’Odéon, Place de l’Odéon – will be there from 1 o’clock to 2? Or could you come to my place 5 Place de l’Odéon (entresol) around 5 to 7 this afternoon? In either case bring Miss Miller is she is with you and cares to come – In haste, Seabrook’.

Appendix B

Correspondence from William Seabrook to Man Ray, Undated, MANR6, Fonds Man Ray, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France.

‘I’ve got some additional tentative ideas, to go along with the black mask: A black priest’s robe and priest’s shovel hat – straight line such as one sees priest’s wear in the street. Concealed beneath it a wasp-waist hour-glass corset finished either in some glittering fabric that looks likes polished steel, or in black leather-like material to match the mask. Also boots or slippers with fantastically high heels. So if you will be thinking of where you might send me to order these various things, in addition to the two we spoke of yesterday, I will be much obliged. Unless I hear from you to the contrary, I’ll bring the young woman by your studio for a little while around five thirty this afternoon’. Correspondence from William Seabrook to Man Ray, Undated, MANR6, Fonds Man Ray, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France.

Acknowledgments

For the patient and helpful guidance they provided with an earlier version of this article, I thank Katherine Brion and Gavin Parkinson. I would also like to thank Damarice Amao and Julie Jones of the Musée national d’art moderne for providing me with the invaluable opportunity to view these works in person, as well as the staff of the Bibliothèque Kandinsky and the Getty Research Institute for allowing me access to the Man Ray Archives.

Audrey Warne is the 2020-2021 Getty Graduate Intern in Digital and Print Publications. She graduated from The Courtauld Institute of Art in 2020 and studied under Prof Gavin Parkinson’s Modernism After Postmodernism: Twentieth Century Art and Its Interpretation MA Special Option.

Citations

[1] See, for example, Robert James Belton, The Beribboned Bomb: The Image of Woman in Male Surrealist Art (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 1995).

[2] Katharine Conley, Surrealist Ghostliness (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2013), 93.

[3] See, for example, Mary Ann Caws, Rudolf E. Kuenzli, and Gwen Raaberg, eds., Surrealism and Women (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995).

[4] David Bate, Photography and Surrealism: Sexuality, Colonialism and Social Dissent (London: Tauris, 2011), 162.

[5] Amy Lyford, Surrealist Masculinities: Gender Anxiety and the Aesthetics of Post-World War I Reconstruction in France (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 2007), 116.

[6] David Hopkins et al., A Companion to Dada and Surrealism (Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2016), 357.

[7] See, for example, Sigmund Freud and James Strachey (transl.), Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (Mansfield Centre: Martino Publishing, 2011).

[8] Freud and Strachey, 38.

[9] See, for example, Angela Dworkin, ‘Pornography and Grief’, in Feminism and Pornography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 39-44.

[10] Georges Bataille and Michel Leiris, Documents : Doctrines, Archéologie, Beaux-Arts, Ethnographie (Paris: Jean-Michel Place, 1991), 461-466.

[11] The original title of the piece was ‘Le ‘Capuut Mortem’ ou la femme de l’alchimiste’. (Unless cited, all translations are by the author.)

[12] I have been unable to locate a high-quality reproduction of the 3rd image included in Documents, and I am, therefore, unable to make claims about its content.

[13] For more contemporary scholarship on sadomasochistic play’s ability to promote altered states of consciousness see James K. Ambler et al., ‘Consensual BDSM Facilitates Role-Specific Altered States of Consciousness: A Preliminary Study,’ Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice 4.1 (March 2017), 75-91.

[14] See William Seabrook, Witchcraft: It’s Power in the World Today (London: White Lion Publishers Limited, 1972).

[15] In his autobiography, Seabrook describes a photograph taken of Justine wearing the mask that was published in conjunction with an article by Leiris on the psycho-erotic aspects of masking which indicates to me that the images published in Documents are same images mentioned by Seabrook and, therefore, feature Justine as the model. Seabrook, 246.

[16] Seabrook, 246-247.

[17] Seabrook, 247.

[18] ‘On peut tirer une jouissance profonde (en même temps érotique and mystique, comme tout ce qui est sous le signe de la complète exaltation) du simple fait de masque – ou de nier un visage’. Leiris, 463.

[19] ‘On touche ici, d’ailleurs, à la source du fétichisme érotique, très proche du fétichisme religieux et du culte de reliques, parce que s’y manifeste un même mode de pensée magique, tel que la partie est prise pour le tout, l’accessoire pour la personne, et que la partie y est non seulement égale au tout, mais même plus forte que le tout, comme un schéma est plus forte que l’objet qu’il représente, partie ou schéma étant des sortes de quintessences, plus émouvantes et expressives que le tout, parce que plus concentrées, et aussi moins réelles, plus extérieures à nous, plus étrangères, assimilables à des déguisements par lesquels la réalité – et, en raison de cette ambiance, l’homme lui-même – est métamorphose’. Leiris, 465.

[20] ‘… un même mode de pensée magique, tel que la partie est prise pour le tout, l’accessoire pour la personne, et que la partie y est non seulement égale au tout, mais même plus forte que le tout…’ Leiris, 465.

[21] See Roy F. Baumeister, ‘Masochism as Escape from Self’, Journal of Sex Research 25.1 (1988), 28-59.

[22] Jerrold E. Siegel, Bohemian Paris: Culture, Politics, and the Boundaries of Bourgeois Life, 1830-1930 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1999), 375-376.

[23] See, for example, Jean-Michel Rabaté, ‘Loving Freud Madly: Surrealism between Hysterical and Paranoid Modernism’ in Journal of Modern Literature 25.3/4 (2002), 58–74.

[24] Lyford, 143.

[25] The same images published in Documents were later requested by Man Ray on behalf of Louis Aragon, presumably for publication in another surrealist magazine. Correspondence from William Seabrook to Man Ray, 22 August 1930, MANR6, Fonds Man Ray, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France. See Appendix B.

[26] See, for example, Hal Foster, ‘L’Amour Faux’, Art in America (January 1986), 117-128; Rudolf Kuenzli, ‘Surrealism and Misogyny’, Dada/Surrealism 18 (1990), 17-26.

[27] Hopkins (2016), 357.

[28] Referring to such practices as ‘dervish dangling’ is unique to Seabrook, indicating that he was perhaps involved in the staging or costuming of Gloved Figure, as the phrase ‘dervish dangling’ is written on the back of the print in pencil.

[29] Seabrook, 232-234.

[30] While 6 prints exist in the collection of the Musée national d’art moderne, there could potentially be more prints associated with this series.

[32] See, for example, D.A.F. Sade, Will McMorran, and Thomas Wynn (transl.), The 120 Days of Sodom (Penguin Classics, 2016); Gilles Deleuze and Leopold Sacher-Masoch, Masochism: Coldness and Cruelty and Venus in Furs (New York: Zone Books, 1991), 143-271.

[33] Neil Cox, ‘Desire Bound: Violence, Body, Machine’, in A Companion to Dada and Surrealism, 334-351; Bate, ‘The Sadean Eye’ in Photography and Surrealism, 145-171.

[34] Past exhibitions on Sade’s influence on surrealism: Quentin Bajc and Chérux Clément, La Subversion Des Images: surréalisme, Photographie, Film [exhib. cat.] (Paris: Éditions du Centre Pompidou, 2009); Tobia Bezzola and Michael Pfister, Sade Surreal: Der Marquis De Sade Und Die Erotische Fantasie Des Surrealismus in Text Und Bild [exhib. cat.] (Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz, 2001); Annie Le Brun, Attaquer Le Soleil [exhib. cat.] (Paris: Musée D’Orsay et de l’Orangerie, 2014); Jennifer Mundy, Surrealism: Desire Unbound [exhib. cat.] (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 2001).

[35] Georges Bataille, Eroticism (London: Penguin Classics, 2012), 190.

[36] Bataille, 187.

[37] See Phillip Prodger, Antony Penrose, and Lynda Roscoe, Man Ray Lee Miller: Partners in Surrealism, (Salem: Peabody Essex Museum, 2011); Whitney Chadwick, Farewell to the Muse: Love, War and the Women of Surrealism, (London: Thames & Hudson, 2017).

[38] Prodger, 31.

[39] Seabrook’s letters to Man Ray explicitly mention Miller, indicating she knew Seabrook well and was a part of many of Man Ray’s interactions with him. Correspondence from William Seabrook to Man Ray, Undated, MANR6, Fonds Man Ray, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France. See Appendix A.

[40] Man Ray, 193.

[41] Correspondence from William Seabrook to Man Ray, Undated, MANR6, Fonds Man Ray, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France. See Appendix B.

[42] Janine A. Mileaf, Please Touch: Dada and Surrealist Objects after the Readymade (Hanover: Dartmouth College Press, 2010), 67.

[43] Hopkins (2016), 336.

[44] While 9 negatives exist in the collection of the Musée national d’art moderne, there could potentially be more negatives associated with this series.

[45] Damarice Amao in conversation with the author (26 February 2020).

[46] See, for example, Allan Sekula, ‘Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation)’, in Photography Against the Grain: Essays and Photo Works 1973-1983 (London: Mack, 2016), 53-76.

[47] See, for example, Patrick D. Hopkins, ‘Rethinking Sadomasochism: Feminism, Interpretation, and Simulation’, Hypatia 9.1 (1994), 116–141.

[48] Hopkins (1994), 123.

[49] Linda Williams, Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and the ‘Frenzy of the Visible’ (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2010), 17.

[50] Williams, 18.

[51] The relationship between BDSM and trauma has been an increasingly studied topic by both psychologists and sociologists. See, for example, Corie Hammers, ‘Corporeality, Sadomasochism and Sexual Trauma’, Body & Society 20.2 (2013), 68–90.

[52] Michel Foucault and Robert Hurley (transl.), The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction (Camberwell, Vic.: Penguin, 2008), 36-37.

[53] See the original transcription of these discussions in: José Pierre, Recherches sur la sexualité, janvier 1928 – août 1932 (Paris: Gallimard, 1993), and an English translation of the transcription in: José Pierre and Malcolm Imrie, Investigating Sex: Surrealist Discussions, 1928-1932 (London: Verso, 1992).

[54] See, for example, André Breton’s homophobic comments in Pierre (1992), 27-28.

[55] Pierre, 130-132.

[56] Pierre, 131.

[57] Pierre, 131.