Courtauld MA Conservation of Easel Paintings students helped to conserve five 17th and 18th century portrait paintings from the collection at English Heritage’s Audley End House from 2020 – 23.

The paintings, by the Dutch artists Maria Verelst (1680–1744), Willem Wissing (1656–87) and an unknown 17th-century artist working in the manner of Sir Anthony Van Dyck (1599–1641), were in varying condition. Their conservation history meant each painting posed a unique challenge for the students.

Read more about the challenges of cleaning and retouching these works, and how our students addressed them. You will find a gallery images at the bottom of this page.

The Conservation project

The conservation studio at English Heritage has collaborated with the Courtauld Institute of Art in London for many years, supplying paintings from historic house collections for their students to work on. This gives the students high-quality works on which to develop their skills, while English Heritage benefits from their world-class technical analysis facilities.

In 2020, five of Lady Jane’s family portraits were transported to the Courtauld and worked on by students Kyoko Takemura, India Ferguson, Saffie Patel, Jack Chauncy and Lily Spencer.

All the paintings had different conservation needs: some of the cleaning was more complex than others and in some cases, the canvases needed to be repaired. The students looked closely at the materials and techniques of the paintings to learn more about the artists’ processes and help determine the best way forward for the treatment.

Charles Cornwallis

Charles, 4th Baron Cornwallis (1675–1722), was Lady Jane’s great-great-grandfather. He lived at Brome Hall in Suffolk and was the MP for the local town of Eye. The portrait of Charles by Maria Verelst was in largely untouched condition and had never been taken off the strainer (the original wooden frame over which the canvas is stretched). This was very unusual for a painting of this date and may help to explain its remarkably good condition.

However, the canvas was not securely attached to the strainer, its edges were degraded and the original strainer required replacement. The canvas was therefore reinforced by adding strips of fabric to the edges (a ‘strip lining’) which allowed it to be stretched onto the new custom-made stretcher.

Courtauld student Jack Chauncy, who treated the painting, explains:

“A strip-lining is a more minimal approach to full lining, where the entire back of the canvas is adhered to another fabric. I used a polyester textile, normally used to make sails, to make the strips.”

This type of fabric reduces how the painting reacts to changes in moisture in old buildings.

Charlotte Cornwallis

Another portrait by Maria Verelst depicts Lady Charlotte Cornwallis (1679–1725), who was Lady Jane’s great-great-grandmother and the wife of Charles Cornwallis.

Courtauld student Lily Spencer used x-ray and infrared imaging to reveal that it had suffered from significant cracking and flaking in the past due to moisture damage. Unfortunately, previous restorers had simply retouched over the areas that had flaked away instead of addressing the root of the issue. Over time this caused more flaking, and more of the original paint was covered up by further retouching. Luckily, in the mid-1980s the canvas was lined onto a new piece of canvas, which solved the flaking problem. However, the old layers of discoloured retouching were still evident and Lily was faced with a challenging retouching process.

Conservation ethics had to be considered at every stage of the process. Lily explains:

“In modern conservation practice we have to maintain the principle of ‘reversibility’; anything that we add to the painting must be reversible. So, for our retouching paints, we now use powdered pigments ground in synthetic varnish. This can easily be removed with solvents which won’t affect the original paint. When the painting was restored in the 19th century the restorer used oil paint, which had become hard and difficult to remove. The primary aim of our treatment was to remove as much of this non-original paint as possible, to restore the original composition.”

Elizabeth Ashburnham

Elizabeth Ashburnham, Lady Cornwallis (1610–43), was Lady Jane’s great-great-great-great-great-grandmother. She was the wife of Frederick, 1st Baron Cornwallis, and lived at Brome Hall. Her portrait, treated by Courtauld student Kyoko Takemura, was painted by a follower of Sir Anthony Van Dyck.

After cleaning the painting, Kyoko faced a big retouching challenge:

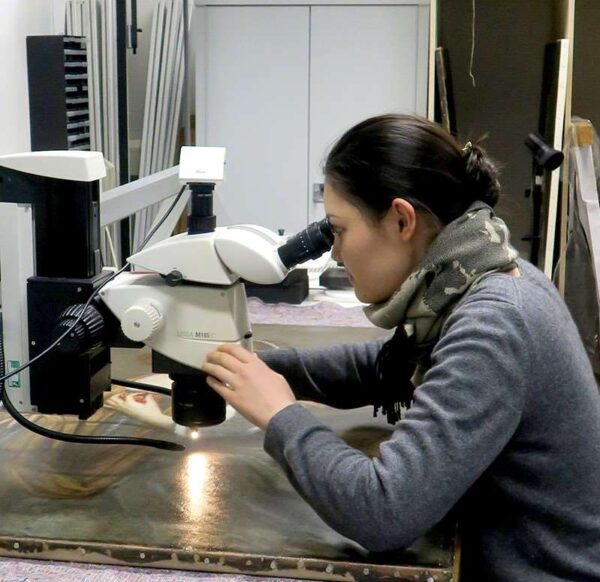

“The dress had lost most of its modelling, leaving light grey and dark blue streaks which was hard to read. The grey paint had formed a strange globule like texture, leaving the brown underlayer exposed…A tiny paint sample from the skirt was examined under the microscope to find a layer of smalt paint over a dark-coloured paint. Smalt is made from ground up tinted blue glass and it tends to lose the blue hue and become translucent as it ages, which is why the dress now appears grey. The globules formed because the smalt paint dried too quickly due to its glass content which accelerates the drying process.”

The change in colour balance meant it was difficult to visualise how the painting would have looked originally. There were also multiple pentimenti (compositional alterations made by the artist as they worked) which became visible due to degradation. Together, conservators and curators decided to tone down the light grey streaks, reinforce abraded paint, and suppress the traces of pentimenti. This has improved the coherence of the drapery while the viewers are still able to see hints of the history of the painting.

Isabella Scott

Lady Isabella Scott (1690–1748), depicted in another portrait by Maria Verelst, was Lady Jane’s great-great-aunt. She was also the half-sister of Charles Cornwallis (above) whose mother died at a young age. Their father, the 3rd Baron Cornwallis, remarried, and Isabella was born to his second wife.

The conservation of this painting aimed to address aesthetic issues caused by previous restorations. Courtauld student Saffie Patel, who worked on the painting, explains the challenge:

“A natural resin varnish had been applied during a previous historic treatment and had since discoloured to obscure and muddy the bright colour palette that the artist intended. Retouching had been liberally applied in oil paint, which had also discoloured. These were both successfully cleaned away over many hours, with small swabs and carefully designed solvent mixtures, to reveal undamaged original paint.”

The painting had previously been attacked by woodworm, a pest which burrows tiny holes in wood, and had weakened the stretcher. These holes were consolidated and filled. Finally, the damaged areas were retouched with reversible pigments on top of a new protective varnish layer, ensuring their safe and easy removal in the future if necessary. The blue drapery was retouched with a minimalist approach to retain a sense of the painting’s age and history within the larger group of portraits.

Dorothy Butler

Dorothy Butler (1650–1716), Countess of Arran, was Lady Jane’s great-great-great-grandmother. Her only surviving child, Charlotte, married Charles, 4th Baron Cornwallis (both pictured in portraits by Maria Verelst above).

Dorothy Butler’s portrait by Willem Wissing was aesthetically in relatively good condition with few signs of damage and minimal overpaint. Courtauld student India Ferguson surface cleaned the painting using cotton swab sticks moistened with saliva to remove any surface dirt and dust. Saliva is a great cleaning agent for most historic paintings. The varnish was also removed and small amounts of retouching done.

Structurally the painting was in a less stable condition with prominent cracks and an undulating surface. India describes her process:

“The painting had been lined onto another canvas previously, but this had detached over time as the glue failed and was no longer serving its purpose. Therefore, the original canvas was taken off the lining canvas – a big intervention as it involved removing the painting from its fixed strainer. The painting was then ‘strip lined’ (where strips of canvas are used to reinforce the edges of the painting) which allowed it to be re-stretched. This reintroduced good tension to the painting and means that the edges are now better supported.”

Original article posted on English Heritage website.

Gallery

Expand the images below to see the students in progress, and the paintings after treatment.

All photographs are courtesy of The Courtauld, Department of Conservation.