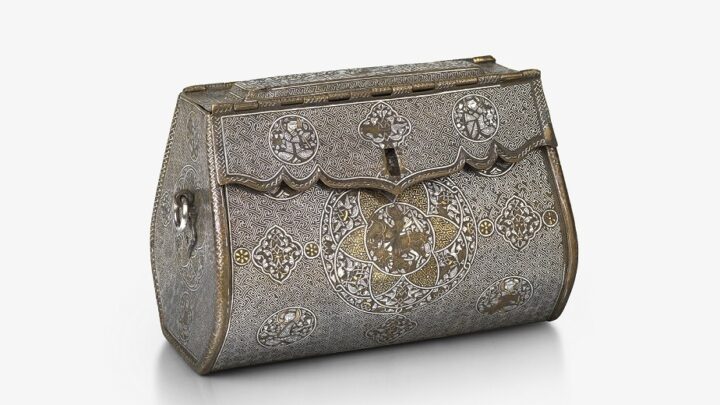

Tile with sunburst, a device of the Gonzaga family of Mantua

The workshop of Antonio dei Fedeli, Pesaro

By Dr Guido Rebecchini, Associate Dean for Students (2019-2021) and Reader in Sixteenth-Century Southern European Art at The Courtauld

In the 15th century, floor tiles of tin-glazed earthenware (called maiolica) were rare luxury furnishings, made according to the clients’ designs.

This tile is one of a larger set commissioned by the Marquis of Mantua Francesco II Gonzaga (1466-1519, ruled from 1484) from the workshop of Antonio dei Fedeli in Pesaro in 1493. They were ordered for a room in Marquis Francesco’s residence, Marmirolo, outside Mantua.

A number of spare tiles, however, remained in Mantua and were given to his wife Isabella d’Este (1474-1539), who used them in a small studiolo, which she would eventually adorn with paintings by Andrea Mantegna, Pietro Perugino and others, ancient and modern sculptures, including a lost Sleeping Cupid by Michelangelo, and small reproductions in bronze of ancient statues.

Amusingly, a letter of 1494 reports that the installation of the new floor helped eradicate an infestation of rats which had made nests under the floorboards. The tiles, many of which survive, feature Marquis Francesco’s family imprese. Composed of a body (the image) and a soul (the text), imprese were popular expressions of a symbolic language which celebrated the virtues of their patron.

This tile shows an enigmatic impresa with a radiant sun and the text “per un dixir” (“for a desire”). The impresa was devised for Marquis Ludovico II Gonzaga (1412-1478) in 1448, and although its meaning remains elusive to this day, it became ubiquitous in Mantua. The combination of desire and the sun seems to allude to the aspiration to ascend to a divine sphere, perhaps similarly to the Latin dictum “per aspera ad astra”, meaning “through hardships to the stars”. Interestingly, imprese could be passed on through generations like coats of arms. They could also be assigned to people outside the family to create bonds of loyalty and allegiance. In the case of this impresa, Marquis Ludovico bestowed it upon his court artist, the great painter Andrea Mantegna, in whose house it can still be seen today.

See this object in The Courtauld Gallery

See more collection highlights

Explore The Courtauld’s remarkable collection of paintings, prints and drawings, sculpture and decorative arts.