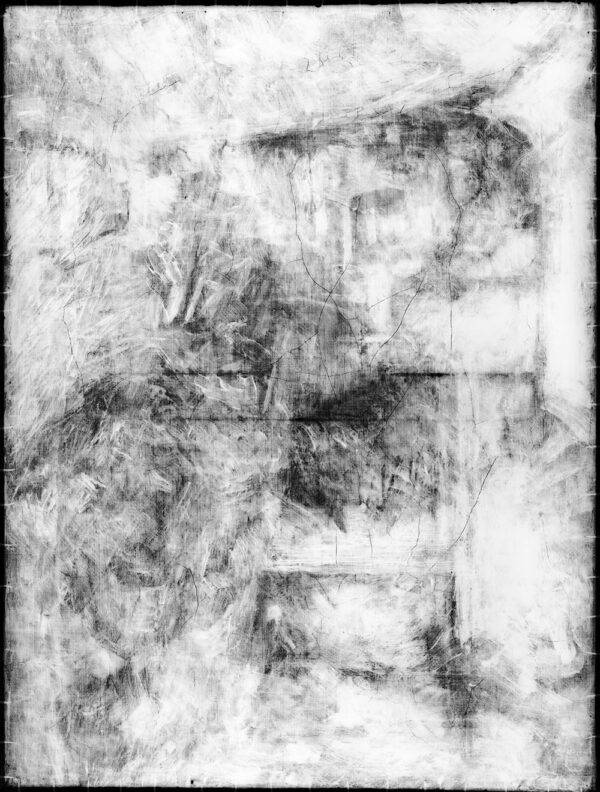

An undiscovered painting by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) of a mystery woman, hidden for more than a century beneath one of the very first paintings from the artist’s famous Blue Period, has been revealed by conservators at The Courtauld Institute of Art using specialist imaging technology to examine the work for the first time.

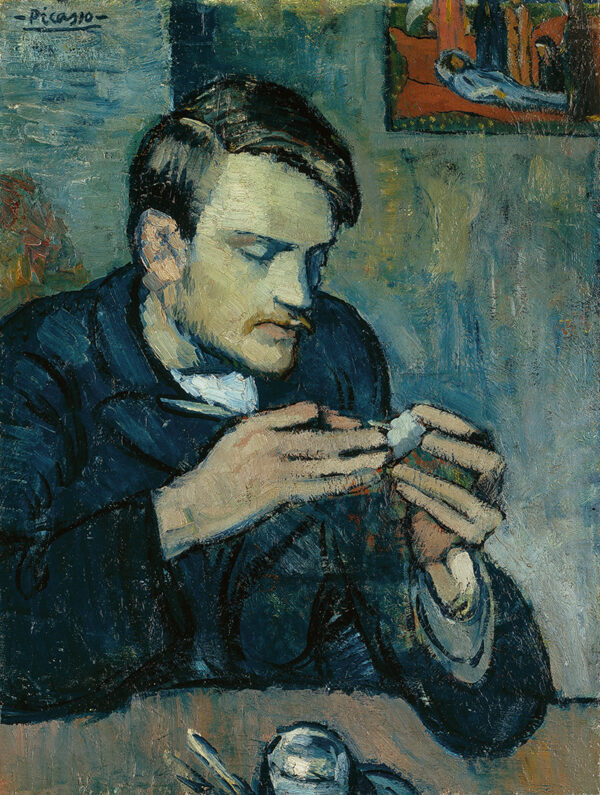

Conducted in collaboration with the Oskar Reinhart Collection, ‘Am Römerholz’, Switzerland, the unknown artwork was discovered when The Courtauld took x-ray and infrared images of Portrait of Mateu Fernández de Soto – a portrait depicting Picasso’s sculptor friend painted in 1901 and one of the earliest examples of the artist’s Blue Period – ahead of its display as part of the upcoming The Griffin Catalyst Exhibition: Goya to Impressionism. Masterpieces from the Oskar Reinhart Collection, opening 14 February.

The Courtauld’s analysis of the painting reveals it played an important role at a crucial stage in the young Picasso’s stylistic development, at a time when he was moving away from colourful, Impressionistic paintings towards a distinctly more melancholy artistic style which became the defining phase of his career known as his Blue Period.

Portrait of Mateau Fernández de Soto and Picasso’s Blue Period

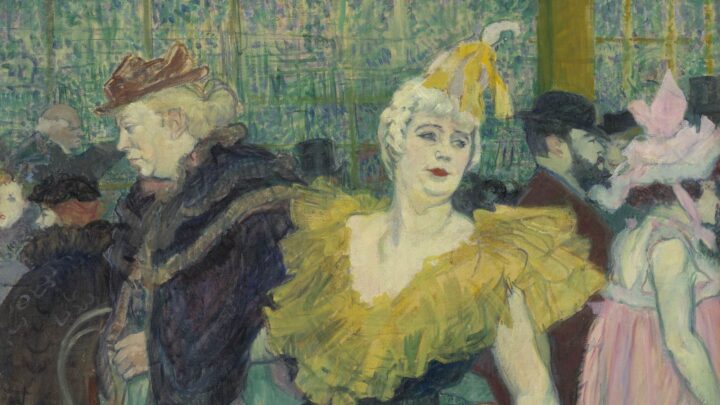

Portrait of Mateu Fernández de Soto is emblematic of Picasso’s sombre Blue Period, hailed as a defining moment in his career. Nineteen-year-old Picasso had arrived in Paris from Spain in May 1901 for his first exhibition in the city, which opened at the gallery of the modern art dealer Amboise Vollard the following month. Picasso made a range of paintings for that show in an Impressionistic style, with lively brushwork and bright colour. However, by the Autumn of 1901, when he painted Portrait of Mateu Fernández de Soto, Picasso began to change his artistic style to an approach that was more contemplative and sombre, painted in tones of blue.

This Blue Period was inspired in part by the suicide earlier that year of Picasso’s good friend Carlos Casagemas. Picasso took over the rooms where Casagemas had lived in Paris and set up his studio there. Another friend, the young Spanish sculptor Mateu Fernández de Soto, arrived in the city in the Autumn of 1901 and was staying in this studio with Picasso where this portrait was made. The painting on the wall in the background of Portrait of Mateu Fernández de Soto is one of Picasso’s memorial paintings depicting the burial of Casamegas.

Analysis and discoveries

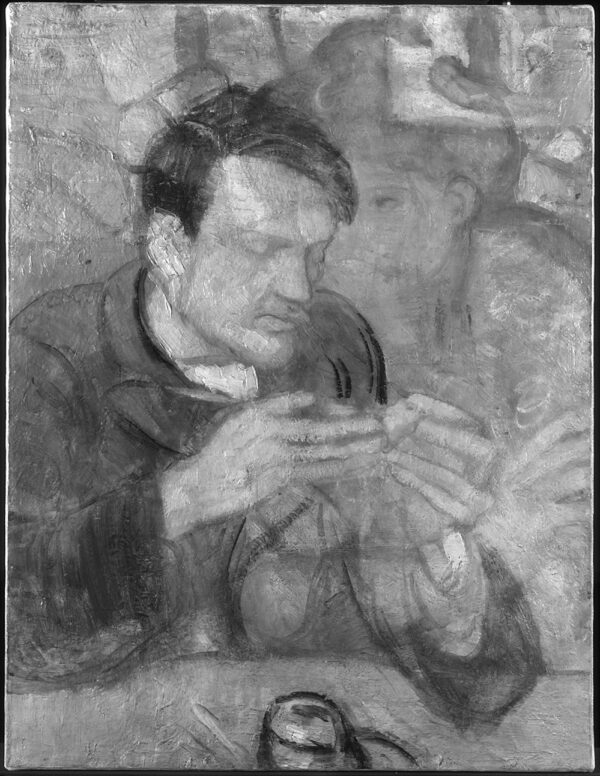

Infrared and x-ray images beneath the contemplative portrait of de Soto have revealed another figure, a painting of a woman, likely created just a few months earlier. The form of her head, curved shoulders and the fingers can clearly be seen. Wearing a distinctive chignon hairstyle, fashionable in Paris at the time, she bears a resemblance to several paintings of seated women that Picasso made that year, such as Absinthe Dinker (Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg) and Woman with Crossed Arms (Kunstmuseum, Basel). There is also evidence of a further head at an even lower level in the painting, suggesting it was a much-reworked canvas. She might have been a figure painted in his earlier Impressionistic style, akin to the painting of a woman in shimmering colours called Waiting (Picasso Museum, Barcelona).

Further research into the painting and detailed analysis could reveal more about the mystery woman, but it is not certain her identity will be established. She may have been a model, a friend or even a lover posing for one of Picasso’s colourful Impressionistic images of Parisian nightlife, or a melancholic woman seated in a bar.

Picasso often reused his canvases at this time because he did not have much money. However, he also embraced the process of painting one work over another, resisting whitewashing old images in favour of beginning a new figure directly on top of an earlier one. It is as if the portrait of de Soto grew out of the figure of the woman below as one style gave way to another.

“This is truly a picture of great complexity, revealing its secrets over the years. When Oskar Reinhart acquired it in 1935, it was simply considered to be a portrait of an unknown woodcarver. Now we not only know the personality depicted, his significance in Picasso's life after the death of his closest friend, but we can also visualise the artistic development process of the young painter layer by layer.”Kerstin Richter, Director of the Oskar Reinhart Collection

“We have long suspected another painting lay behind the portrait of de Soto because the surface of the work has tell-tale marks and textures of something below. Now we know that this is the figure of a woman. You can even start to make out her shape just by looking at the painting with the naked eye. Picasso’s way of working to transform one image into another and to be a stylistic shapeshifter would become a defining feature of his art, which helped to make him one of the giant figures of art history. All that begins with a painting like this.”Barnaby Wright, Deputy Head of The Courtauld Gallery

“Specialist imaging technology such as that used by conservators at The Courtauld may allow us to see the hand of an artist to understand their creative process. In revealing this previously hidden figure we can shed light on a pivotal moment in Picasso’s career.”Aviva Burnstock, Professor of Conservation at The Courtauld

See this artwork on display in The Griffin Catalyst Exhibition: Goya to Impressionism. Masterpieces from the Oskar Reinhart Collection, from 14 February – 26 May 2025.