If a painting is regarded primarily as an attempt to present surface as embrasure or, in the words of Leon Battista Alberti, ‘an open window through which the subject to be painted is seen,’ then the pictorial edge poses a problem.1 Such an illusion is most vulnerable at the site of transition between artifice and reality, so that true instances of trompe l’oeil either depict objects in their entirety or visually excuse their edges as a niche or aperture. Reflecting on the problematic status of the parergon, Jacques Derrida argued that the proper characteristic of the frame is ‘not that it stands out but that it disappears, buries itself, effaces itself, melts away…’2

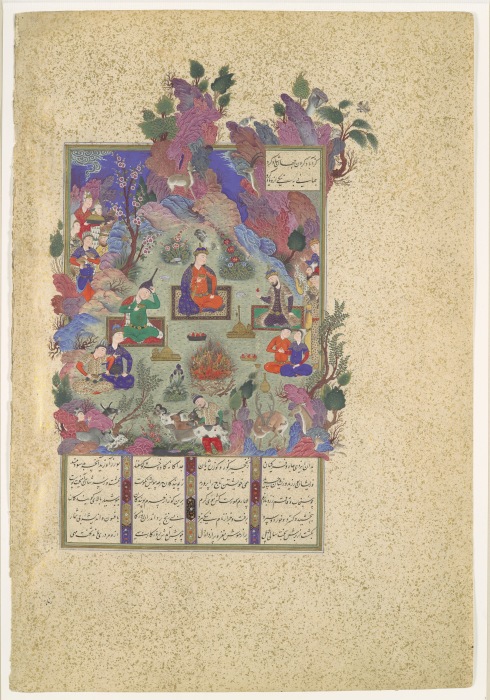

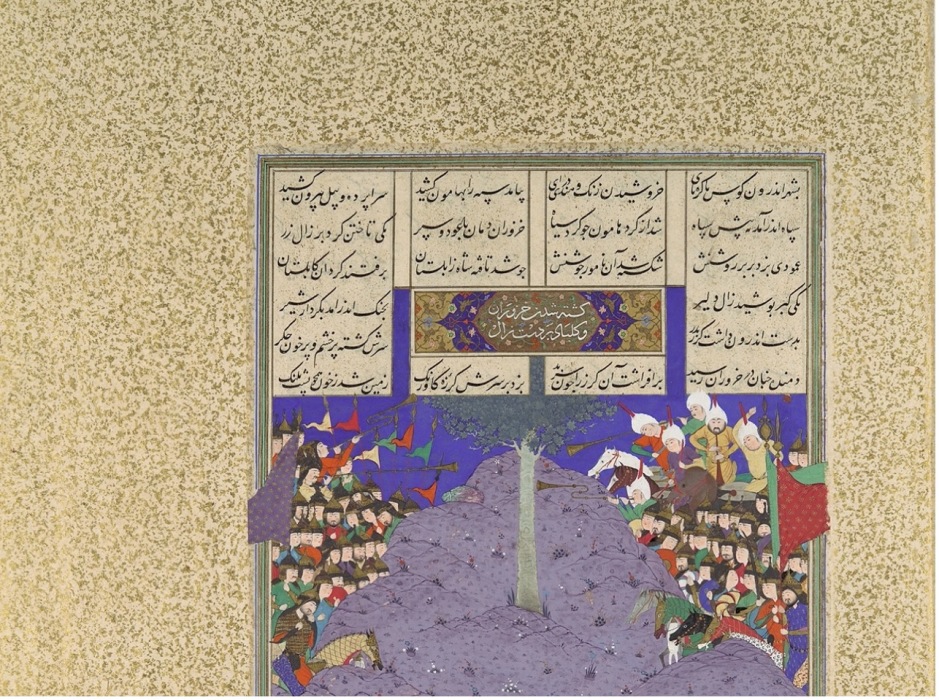

By contrast, the painting of ‘The Feast of Sadeh’ (Fig. 1) is neither a negation of surface, nor does it remotely try to efface the picture’s edge.3 The image depicts a feast to celebrate Hushang’s discovery of fire and is taken from the magisterial manuscript of Ferdowsi’s Shāhnāmeh dedicated to the second Safavid ruler, Shah Tahmāsp (1524-1576). Despite the serious tenor of Iran’s national epic, written at the turn of the eleventh century CE, the artist, Soltān Mohammad, has lavished attention on a wealth of lively cameos that surround the primary narrative scene and animate the edges of the painting. From the bottom left, two bulky cows and a comically braying donkey emerge implausibly from a small collection of polychromatic rocks, while nearby a shepherd man-handles an alarmed goat across a stream. At the bottom right, two gazelles attempt to escape the picture, while above quail and gazelles cavort among pink and purple rocks, which tease the viewer with hidden faces and figures. The real troublemaker, however, is the grey bear, top right, who is about to cast a large rock onto the crouching leopard below. The leopard in turn eyes a pair of songbirds, one of which flies completely free of the image amidst the golden flecks.

While these cameos emphasise both the edge and the artifice of the work by self-consciously ‘playing up’ to the audience, a more subtle interrogation of the picture’s edge is at work. Why is it, for example, that the group of figures in the top left of the painting are decisively cut off by the picture frame, while the pink and maroon rocks beneath them freely break the picture’s rulings? Similarly, the clouds are contained by the picture frame, while large sections of the rocky outcrop erupt out of the pictorial field. Indeed, the rocks around the text panel are even more inconsistent, with some extending behind the gold and green frame, while others are permitted in front of it. Most subtly of all, to the right of the text panel, a reddish sliver of rock emerges from behind the gold rulings, but in front of the outermost blue line (Fig. 1).

This paper will explore the variety and significance of devices like these, which problematise the status of the image via the pictorial edge. Although some of these strategies were long-standing, they were deployed with particular intensity in the Shāhnāmeh of Shah Tahmāsp, the focus of this study. This manuscript, now regrettably dismembered and dispersed, may have been initiated by the founder of the dynasty, Shah Esmāʿil, but was almost entirely overseen by his son, from the start of his reign in 1524 to the addition of two final miniatures in 1540.4 The pictorial density of the commission, amounting to 258 paintings in a manuscript of 759 folios, meant that it consumed almost all the resources of the royal workshop in Tabriz for over a decade, making it an enormously significant document for early Safavid artistic production. Existing scholarship has focused on precisely this aspect, treating the manuscript as a narrative of stylistic development towards the so-called ‘mature height’ of the Safavid style in Shah Tahmāsp’s second great commission, a Khamseh of Nezāmi, now at the British Library (Or. 2265).5 Although it is correct to describe the later Khamseh as more uniform in style, such a narrative has presented the Tahmāsp Shāhnāmeh as a flawed artistic waypoint, rather than a profound and multifaceted masterpiece in its own right. More recent scholarship on the manuscript has been surprisingly thin on the ground, though Robert Hillenbrand has usefully contextualised this extraordinary project in relation to other royal Shāhnāmehs and situated it in a broadly threatening historical context, in which it no doubt stood as a patriotic, optimistic statement of dynastic ambition.6

This paper focuses, instead, on apparently marginal aspects of these paintings, arguing that the wafer-thin design and playful violations of the pictorial edge in the Shāhnāmeh of Shah Tahmāsp represent a self-conscious and sophisticated interrogation of the nature and limits of the painted image. In this way, the pervasive inconsistency of style in this manuscript—previously censured in Western scholarship—is repositioned as a central, purposeful element, which celebrates the painted page as both surface and fictive arena. Whether this artistic approach extended to other genres of manuscript painting is beyond the scope of this study, but perhaps the imaginative vigour of the poetic epic was particularly conducive to pushing at the limits of depiction.

This argument begins with a brief overview of the interpretation and theory of pictorial frames, in which a comparison with European manuscripts is used to emphasise the ontological implications of different forms of visual framing. We then examine the design of the pictorial rulings or jadval, and manipulations of this frame, before considering the developments and meanings of margin design during the sixteenth century. These artistic edges were the product of several collaborating artists, and each element reflects differently upon the nature and ontology of the image within. Thus, the slow-moving traditions of jadval and margin design imply more consistent, enduring conceptions of the image, while individual breaks or pictorial extensions could reflect the tone of the text, the patron’s preferences, or the tendencies of an individual artist. The article concludes by surveying the contextual factors which may have encouraged early Safavid painters to take an experimental and stylistically self-conscious approach to their images.

IMPLICATIONS OF THE EDGE

There are several aspects of the so-called ‘classical’ style of early Safavid painting, many of them long-standing, that indicate an understanding of the image as a flat, fabricated surface, from the use of un-contoured patterns and flat planes of colour to compositions that create a planar design rather than the effect of recession.7 However, this study focuses on the pictorial edge because of its potency as a site for making implicit statements about the painted image as both an object and visual illusion. In the first place, this is because any fiction, be it literary or visual, is felt most keenly at its limits, which perform an ‘ontological cut.’8 While interpretative frames can be intimated in many ways, physical borders are places where ‘preconditions of interpretation’ can be established with ‘particular density or saliency.’9 The contrasting material preconditions of manuscript paintings and panel paintings are also most evident at their edges. In the context of a panel or easel painting, physical disjunction usually occurs both between the support and the frame, and between the frame and the wall. Yet, in a manuscript painting, the nature of the frame is inherently arbitrary, since the surface of the folio, in principle, continues uninterrupted by the transition from picture to margin. Indeed, being itself pictorial, there is every reason to treat the frame, not as a mere ‘adjunct’ (to use Kant’s word) to the picture proper, but as an integral part of the composition.10 More radically, the fictionality of the painting’s boundary makes it susceptible to a multitude of transgressions, putting it entirely at the mercy of the artist.

The way in which the pictorial frame can alter the ontological status of the image it contains can be further illuminated by briefly setting Persian manipulations of the artistic edge against the theoretical and visual framing of European manuscript painting. Such a comparison makes it clear that foregrounding the fabricated nature of the manuscript miniature was by no means inevitable. Fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Flemish manuscripts, for instance, witnessed an integration of margin and miniature, effectively erasing the ontological disjunction between image and edge.11 Similarly, in his seminal work The Self-Aware Image, Victor Stoichiță discusses the pictorial structure in Christ in the House of Mary and Martha by Pieter Aertsen, noting that the effect of depicting a biblical scene as viewed through an embrasure was to ‘transform what for centuries had been regarded as painting par excellence into a “framed reality.”’12 While seeming only to defer the placement of the pictorial edge, this strategy fundamentally alters the fictionality of the framed image and liminal status of the margin. Another profound difference in the conceptual framing of the painted field is evident in the use of trompe l’oeil effects in the newly integrated margins of Flemish manuscripts, whether to conjure architectural frames or to create the illusion of so-called strewn borders. As Otto Pacht observed, in his study of the Master of Mary of Burgundy, the increased impression of depth in the main miniature and the protruding three-dimensionality of the border ‘enacted two kinds of illusion,’ one of recession and one of projection.13 Though opposite in direction, these illusions share in denying the presence of the picture surface.

The European tendency to construe a painted page as a single, continuous spatial reality is also significant because it may have contributed to the preference among early scholars of Persian art for pictorial unity and plausibility over stylistic and spatial inconsistencies. Such latent attitudes are evident in the foundational scholarly work on the Shāhnāmeh of Shah Tahmāsp by Antony Welch and Martin Dickson, who described a late fifteenth-century precursor to these paintings as full of delightful ‘errors,’ since certain figures were ‘arbitrarily flat’ and space was treated ‘unrealistically and inconsistently.’14 Many of these same ‘errors’ can be found in the Shāhnāmeh itself, described by the same authors as ‘the Shah’s groping search for a mode of expression,’ showing ‘the steps, including a few stumbles’ towards the mature, unified style of his Khamseh (though recent research has revealed that this manuscript was actually an amalgamation of two others).15 In fact, close analysis of this Shāhnāmeh does not suggest an aspiration towards the stylistic synthesis that is usually thought to characterise early Safavid painting.16 Instead, stylistic variety, visual ambiguities and a purposefully surface-led style emphasise the playful and artificial ontology of the painted surface.

More easily overlooked in this manuscript, but involving all of these artistic issues, is the treatment of the ruled border or jadval. As manuscript paintings expanded to occupy more of the textual field (or matn), the jadvalcame to be the primary and ubiquitous border of Persian manuscript paintings until the development of more complex framing practices for the arrangement of album folios.17 The format of these rulings is powerfully suggestive of both the painting within and the context without. Yet, perhaps because of their universal presence, they have thus far attracted limited scholarly attention.18

MAKING AND BREAKING THE JADVAL

The jadval, meaning a small stream or rivulet, refers primarily to the external rulings that surround the matn. Its dimensions were determined by the mastar, a template that was imprinted on every single folio and served to demarcate columns, line height, and the matn dimensions. While some of the internal rulings would be invisible in the final manuscript, or indicated by minimal lines, the outer jadval was delineated by multiple parallel lines of varying thicknesses and colours. In this way, the jadval reflected and revealed a continuity of organisational design that underpinned the entire manuscript. In the context of later, composite album pages, the main purpose of the jadval became ‘to hide the seams between separate pieces of paper,’19 but prior to this it was primarily a pictorial, conceptual boundary, rather than a mark of physical disjuncture. The jadvaldesign was generally consistent throughout a manuscript and so would probably have been determined by the supervisor of the ketābkhāneh (scriptorium or atelier), though individual artists presumably decided how and when a painting would exceed its boundaries. The actual rulings, however, would have been added later, often by a specialist known as a jadvalkesh.

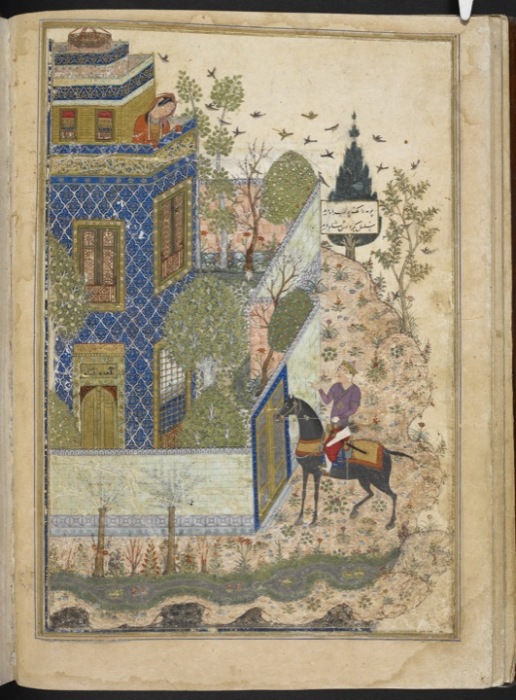

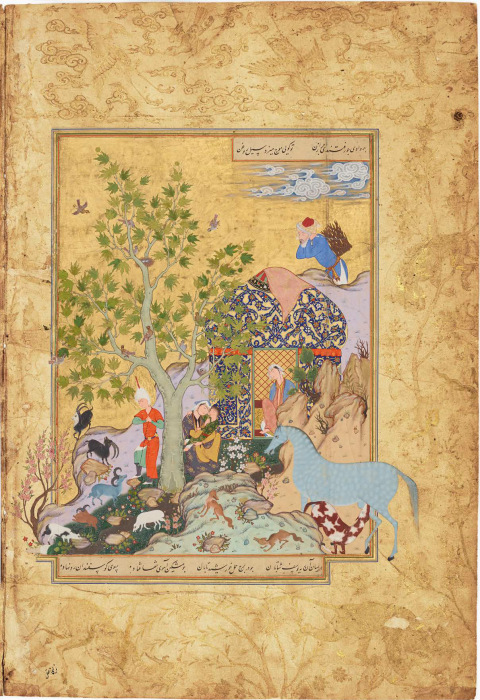

Tracing the development of jadval design is difficult, since the parallel rulings formed an obvious boundary to which margins could be added, either for refurbishment or for the contemporaneous addition of decorated margins, thereby obscuring any divide between older and later rulings. Despite this complication, it appears that by the fourteenth century, Ilkhanid rulings were mostly red and composed of only two thin lines, though Blair notes that the paintings themselves were sometimes framed in lines of blue or gold.20 By comparison, from the late fourteenth century, Jalayirid and Timurid designs favoured gold bands, outlined in black, usually with an outer ruling of blue, a little more distant from the matn (Fig. 2). Although ruling design related not only to period but to the status and perhaps even genre of the commission (the minimal rulings of Ebrāhim Soltān’s Shāhnāmeh, for example, echo the austere aesthetic of the epic-style paintings), it seems that the jadval did become more complex over time.21 Safavid illuminators certainly experimented more with the addition of colour, such as the bright green band in the rulings of the Shāhnāmeh of Shah Tahmāsp (Figs 1, 5, and 7), orange-red and blue bands in a Khamseh dated to 1524-1525 at the Metropolitan Museum (13.228.7) and a varied, complex and colourful programme of rulings in Ebrāhim Mirzā’s Haft Owrang (Fig. 3).22

This development is discernible in a Khamseh at the British Library, Add. 25900, which helpfully includes one painting that is contemporaneous with the text (1442-1443) as well as later additions from two further artistic campaigns: one in late Timurid Herat and another in the early Safavid period. It is therefore possible to compare artistic practices within the format of a single codex. The contemporaneous painting (‘Shirin Contemplates the Third Portrait of Khosrow,’ f. 41a) features rulings with two gold bands (thin inner, thick outer), both outlined in black, followed by a thin black line and a final outer ruling in blue, though on most folios this outer ruling has been redrawn in a darker, heavier hand.23 The late Timurid paintings are almost identical except for the painting of ‘Bahrām Gur in the Black Pavillion’ (f. 173a), which features wide blue and green bands, as well as other idiosyncrasies. The Safavid rulings, however, consistently add in a band of bright orange-red, and sometimes another band of blue or green (Fig. 4). It seems that the principle of consistent jadval design was less compelling by the Safavid period, and this is borne out in the Tahmāsp Shāhnāmeh. While a ruling pattern of gold-green-gold, with an outer blue line, was most common, the thickness of each ruling could vary and extra bands of gold, red, light blue and sometimes even black could be added (for instance, Fig. 6 and Fig. 8).

For an art form that supposedly emphasised the edges of the image, the essence of jadval design may seem strikingly unobtrusive, although the razor-thin parallel lines and careful arrangement of colour and width required great skill and a specialised tool (qalam-e jadval) to be executed flawlessly. Indeed, it is notable that in his treatise on the arts of the book (ca 1606), Qāzi Ahmad describes his own teacher, Mowlānā Muḥammad Amin, as first and foremost a jadvalkesh, and then devotes a long section to the jadval, in which he describes three types of marginal line.24 The detail of his instructions is somewhat obtuse, in terms of line order and the directions to ‘draw a contour’ (an outline?) around each line.25 This is indicative of the author’s aim to give elite Safavid readers a taste of the complexities involved while preserving the aura of virtuosic artistry. Qāzi Ahmad’s comments thereby also indicate salient and valued aesthetic features, such as the fineness of the jadval rulings, stipulating that the space between two lines ‘should be less than the back of the knife.’26

However, their diminutive and incisive form are precisely the point. If the edge is read as a material and philosophical reflection of its object, then the fineness and flatness of the jadval rulings implies the insubstantial thinness of the image, rather than creating the impression either of recession or of the image as three-dimensional object. Meanwhile, their incisive, definitive boundary achieves the shock of an absolute, uncompromising cut—the antithesis of a blurred vignette or an illusionistic, architectural frame. At the same time, the stacking of parallel rulings also facilitated a great deal of subtlety in the most tentative excursions from the picture frame, since an object could break the frame by degrees, rather than all at once.

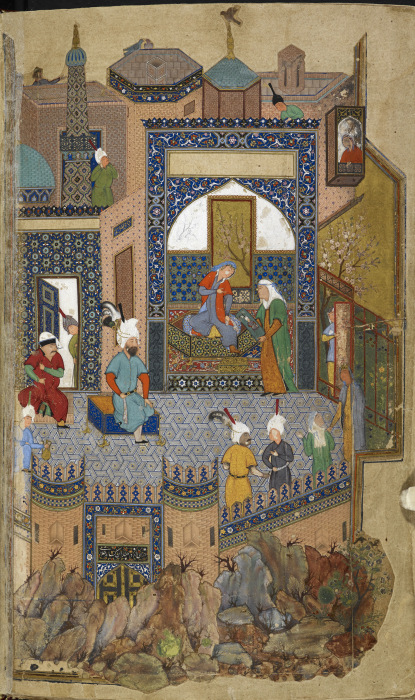

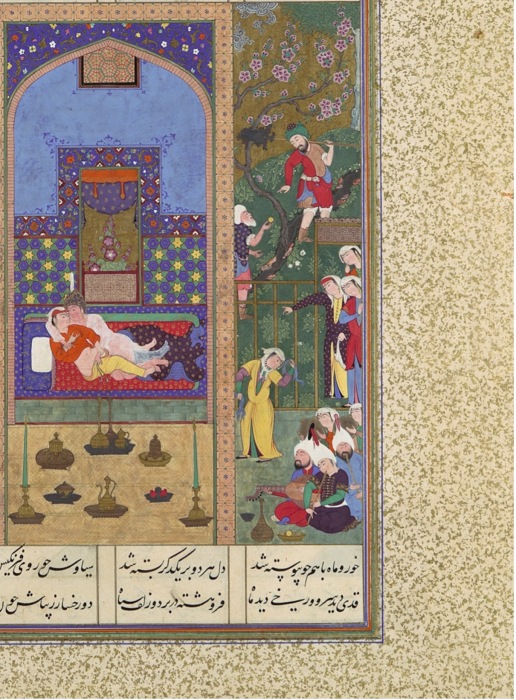

The implied (im)materiality of the razor-fine edge is also demonstrated within the manuscript paintings of the Timurid and Safavid periods, particularly in the depiction of architecture. The practice is evident even in Jalayirid paintings, such as the painting of Homāy and Homāyun from the Khvāju Kermāni manuscript at the British Library (Fig. 2). In this image, the palace walls are depicted as having no girth or substance, a fact evident only at their upper edges. These immaterial, flat planes seem at odds with the painting’s sense of spatial and architectural recession, as if everything in the painted world ultimately refers back to and depends upon the wafer-thin materiality of its paper support. This visual tradition proved remarkably resilient, though in Timurid paintings the flimsy built environment is often allied with more surface-led designs that do not portray the same depth of field as the Jalayrid painting above. Meanwhile, in Safavid paintings, such as the illustration of Nushābeh’s palace (Fig. 4), the papery materiality of the buildings becomes part of a more playful, puzzle-like structure, alongside contrasts of scale (the miniaturised curtain wall in the foreground) and illogical architectural appendages, such as the unsupported upper right chamber.

If the razor-thin rulings pointed to the two-dimensional nature of the painted image, its artificiality was also emphasised, from very early in the history of manuscript painting, by pictorial elements which escaped from its confines. Hillenbrand and Blair have already contributed partial surveys of the progressive breaking of the jadval.27 Both address the origins of the technique, which Hillenbrand traces to thirteenth-century Arab paintings, before analysing the more ‘serious exploration of the device’ that occurred in the late Jalayirid and Timurid periods.28 Blair, meanwhile, notes that significant experiments with marginal incursions were made as early as the late fourteenth century, for example in the Kalileh u Demneh manuscript at Istanbul University Library.29 However, since Blair’s investigation conflates the expansion of the pictorial field with pictorial projections beyond the picture frame, she claims that ‘[b]y the end of the fifteenth century the process of marginal expansion was complete,’ citing the full-page paintings in the Khvāju Kermāni manuscript at the British Library.30 In fact, these are intriguing and unusual examples of framing, with some paintings featuring two sets of rulings: a dark blue band apparently demarcating the matn, and an outer frame, possibly added later, that encapsulates the entire ‘spilled’ landscape (Fig. 2).

The present study builds on Hillenbrand and Blair’s findings by analysing the developments of the broken frame onwards, into the Safavid period, and by focusing on the unusually self-reflexive example of theShāhnāmeh of Shah Tahmāsp. However, Hillenbrand’s underlying premise—that these devices were intended to create a ‘three-dimensional effect’—does not chime with the instructive examples he provides.31 For instance, Hillenbrand is surprised that the Great Mongol Shāhnāmeh, which he describes as intensely concerned with the ‘concept of the framed picture as … a window on a much bigger world,’ does not deploy the device of the broken frame.32 However, it is the very impression of spatial depth which would be dispelled by pictorial elements floating in front of the surface-based jadval. Similarly, Blair’s assertion that marginal incursions aimed to smooth ‘the sharp division between margin and text block’ should be queried.33 Instead, the jadval remained a crucial pictorial element, consistently preventing the unification of painting and margin, and providing a meaningful inside-outside dialectic, even where the painting extended beyond the dimensions of the matn.34

While a comprehensive analysis of Safavid jadval disruptions is beyond the scope of this essay, an early shift in the intensity and character of jadval breaks is discernible. In the fifteenth century, paintings with frame breaks are usually in the minority, and these breaks tend to fall either into the category of minor, conventional breaks (the top of a dome or a tree) or larger breaks which serve to enlarge the arena for narrative action. While Bāysonghor’s Shāhnāmeh, for instance, features a few major extensions into the picture frame, this is achieved simply by eradicating one side of the jadval.35 Where protrusions into the margin go beyond conventional motifs or space-making functions, they seem to serve clear narrative purposes, rather than being self-reflexive in nature. By positioning a figure across the jadval ruling, for example, a painter could dramatise the entry or departure of that character, or suggest their liminal status.36 Meanwhile, the upper edge of a painting was often punctured by a tall tower or dome, which could express the elevated social or spiritual position of the building’s owner, or even function as a visual manifestation of traditional architectural inscriptions that praised the height and grandeur of a royal edifice in hyperbolic terms.37 One such inscription appears on a tower in Bāysonghor’s Golestān of Saʿdi: ‘If the guardian of your castle released a stone, it would [only] reach the roof of Jupiter after a thousand years.’38 The spilling of the picture into the margin could also connote the dynamism of the narrative action or, as Adle comments, the force and momentum of riders in battle.39

More meaningful deployments of the device, however, depend upon the margin being construed as a separate ontological plane. The example of Behzād’s depiction of a funeral procession from the 1487 manuscript of ʿAttār’s Manteq al-Teyr (f. 35r, Metropolitan Museum, 63.210.35), in which a bare-branched, symbol-laden tree emerges from the frame, has been much discussed as a gesture towards life beyond death.40 However, another Timurid Manteq al-Teyr manuscript (British Library, Add. 7735) makes more innovative use of this embedded divide, not by breaking the jadval but by locating the protagonists of the tale—a pair of foxes—in the margin and painting them in ghostly gold, thereby communicating their impending death at the hands of the hunting king, who occupies the main painting and the land of the living (f. 84r). More optimistically, Brend notes that during the fifteenth century, the margin could introduce miraculous elements into a painting, most often angels of inspiration.41

In the sixteenth century, jadval disruptions continue to play a narrative role, but are also explored for their own sake. In addition, a greater bifurcation develops between epic manuscripts, which play freely with extensions into the margin, and romance manuscripts, which may deploy expanded and well-developed compositions but largely stay within their pictorial confines. The didactic Haft Owrang of Ebrāhim Mirzā is an exception, given that only one of its twenty-eight paintings declines to break out of its frame. This perhaps indicates a close alignment in artistic taste between this princely patron and his uncle, Shah Tahmāsp. Towards the end of the sixteenth century, the large-scale luxury manuscripts produced in Shiraz often deployed a much more substantial jadval, with multiple rulings and wider bands of gold, as seen in the Peck Shāhnāmeh, with a colophon date of 1589-1590.42 While the thicker jadval made the artistic edge more prominent, it seems to have presented more of a barrier to the kind of subtle pictorial protrusions that characterise the Shāhnāmeh of Shah Tahmāsp. Nevertheless, it seems that the Tahmāsp manuscript instituted an enduring tradition of breaking the jadval in courtly manuscripts of the Shāhnāmeh, with a few striking experiments still being made in a mid-seventeenth century manuscript illustrated by Moʿin Mosavver.43

A more quantitative indication of the amplified Safavid tendency towards jadval breaks can be achieved by returning to the Khamseh Add. 25900. In this manuscript, the only early Timurid painting deploys no breaks in the jadval, while of the twelve paintings added in late Timurid Herat, nine involve minor breaks, one has none, and the remaining two feature moderate extensions to enlarge the landscape area. By contrast, all of the paintings added in the Safavid period break the jadval, and four out of five involve considerable disruptions on two or more sides, presenting considering difficulty when trimming the paintings (see Fig. 4).

In the Shāhnāmeh of Shah Tahmāsp, however, we find not only an increased quantity of jadval breaks, but a restless and theoretically minded exploration of the edge. The rule is inconsistency. About half the paintings still involve no break at all, but of the paintings which do, around a third feature minor or minute marginal intrusions, while the rest are fairly evenly divided between major breaks into the margins (on two or more sides) and medium protrusions (significant, but limited to a single side). Dickson and Welch attribute this kind of stylistic unevenness to ‘rapid changes’ in pictorial trends, while another explanation could be variation between individual artists.44 However, closer inspection shows that individual painters displayed great variation in their use of pictorial extensions and jadval breaks. It may be the case that the younger generation of painters generally deploy smaller excursions into the margin, though the size of the jadval break was not always commensurate with the ingenuity of the gesture (see Figs 5, 6, and 7).

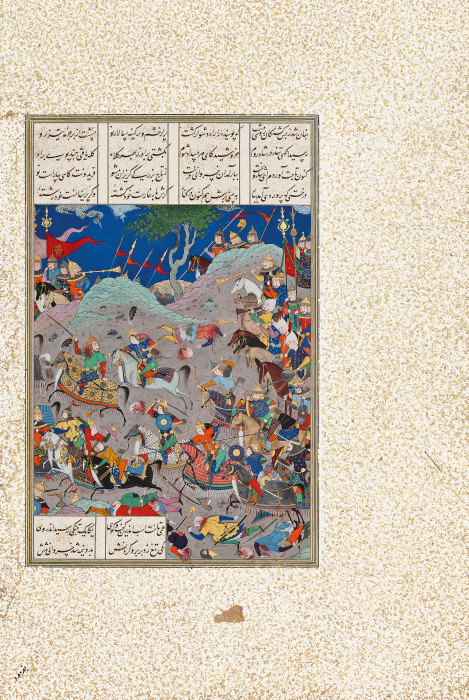

Many pictorial projections simply continued the long tradition of jadval breaks surveyed above, yet even well-established protrusions were given, at times, a new lease of self-conscious subtlety. For example, while flags were long-standing transgressors of the jadval, this manuscript takes an unprecedentedly analytical approach to the motif. In an otherwise unadventurous painting depicting a fight between Zāl and a Turanian commander, the painter has made the curious decision to allow three large flags to pass in front of the jadval, only to cut them off at an invisible edge beyond the outer limit of the ruling (Fig. 5). Additionally, while one is cut cleanly, the flags to the right show a jagged edge. Later on, an otherwise rather archaic sequence of paintings depicting the ‘Joust of the Rooks’ explores this motif in greater detail.45 In most of the paintings, two flags are pitched in the ground and seem explicitly to avoid the rulings by illogically waving inwards. In the sixth joust, though, both flags fly to the left, with one being cut off by the full width of the frame.46 This seems unexceptional, though somewhat unfair given that the small trees at the top of the composition are permitted to grow over the text panel area. In the depiction of the first joust, however, the lefthand flag is given extraordinary attention, as it manages to pass in front of the inner rulings of the jadval, before being inexplicably swallowed up by the meagre outer ruling.47

These examples display a self-conscious attempt to challenge previous norms and to assert that no pictorial convention is sacred. Major incursions into the margin could allow the inclusion of raucous cameos and playful inconsistences, as in the ‘The Feast of Sadeh’ (Fig. 1). The magnificent, multi-level painting of ‘The Nightmare of Zahhāk’ (f. 28v), by contrast, demonstrates how major disruptions to the jadval could be used in a primarily architectural composition, and one with a serious bent, showing the reverberating effect of the evil king’s portentous dream as news of it passes from chamber to chamber within the palace and to the rooftops and gardens beyond.48 Most famously of all, the effervescent, ethereal impression of the ‘Court of Kayumars’ (f. 20v) is in part due to the way that the composition grows organically from the lower edge of the picture frame and rises upwards with trees and rocks spilling from the sides.49 While conveying the paradisical bounty of the scene, the amorphous edge also makes the image appear vulnerable and exposed to the coming evil of Ahriman; this world is unprotected by the safety of the frame and even the rocks dissolve into nothingness.

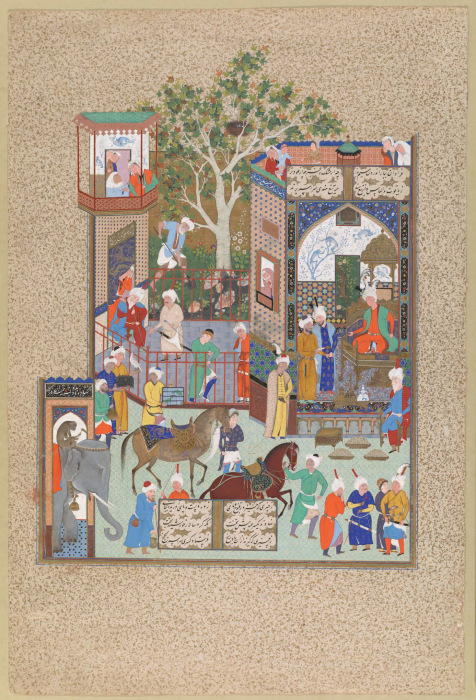

However, it is often the most minute breaks which are most compelling, both because they require the greatest attention from the viewer and because they involve not merely the disruption of the jadval but the interaction of the painting with its own frame. In at least two instances (‘The Wedding of Siyāvosh and Farangis,’ Fig. 6; and ‘Fereydun Receives the Head of Tur,’ f. 56v), a subsidiary figure actually holds onto the rulings as if they were a door frame, thereby interacting with the construct of the page and the world of the viewer. In Figure 6, this wonderful detail both conveys the intimacy of the scene and creates a subtle confusion in terms of space, since the figure holding the frame seems to appear in the image ex nihilo, while other elements of the painting imply a scene that extends beyond the depicted field.

An even more experimental approach is taken in a few battle scenes (ff. 58v, 121v, and 138r), where vigorous fighting is contained within the pictorial field and sometimes dead and wounded figures appear almost to lie on the frame itself. What does escape the picture frame, however, is a spattering of translucent blood, which does not break the jadval but physically stains it, as in the painting of Manuchehr killing Salm (Fig. 7). In this frenzied image, Manuchehr is exacting vengeance for the murder of his grandfather, Iraj, who had been killed by his own brothers, Salm and Tur. The ramifications of this bitter, internecine conflict spill over into the rest of the Shāhnāmeh, fuelling the ongoing feud between Iran and the neighbouring territory of Turan. As such, the blood stain can be seen as both a deeply metaphorical, portentous gesture, and an intellectual artistic device, whereby the jadval is drawn into the fictional plane of the image, while the blood transgresses the ontological caesura and taints the world of the reader.50

Finally, the Shāhnāmeh of Shah Tahmāsp accentuates the pictorial edge, not only in the breech, but in the hyperbolic observance of its ontological cut. Persian painters had long piled up figures at the sides of a battle scene, which would be ostentatiously cut off by the frame. This technique is used frequently in the Shah Tahmāsp Shāhnāmeh in order to suggest a multitudinous army extending beyond the pictorial frame (Fig. 5 being a relatively modest example). However, there are other, more unexpected and humorous deployments of this technique, such as in ‘Nushirvān Receives an Embassy from the Raja of Hind,’ where an elephant enters the painting from a doorway at the bottom left of the picture plane (Fig. 8).51 Given that both painting and folio end with the left side of the doorframe, the space which should accommodate this large and convincingly modelled elephant is amusingly obliterated by the pictorial edge. Numerous other witty manipulations of the picture edge could be mentioned, designed to reward the attentive viewer and to highlight the potential for arbitrary caprice inherent in the fictive arena of the page.

A final element of this dynamic that deserves attention is the role of humour, a topic that demands its own study in relation to Persian painting. The presence of humour has immediate implications for a self-conscious image because it is a ‘social phenomenon,’ requiring the presence of an audience.52 While the kind of burlesque humour found in Figure 1 is by no means a universal principle of the manuscript, humour operates at a more pervasive and fundamental level, whereby ‘an idea, image, text, or event … is in some sense incongruous, odd, unusual, unexpected, surprising or out of the ordinary.’53 In this way, the surprising inconsistency of these paintings both entertains the viewer and draws attention to the mechanisms of depiction.

MEANINGFUL MARGINS

An intensified interest in the folio’s edge can also be deduced from the emergence of various kinds of marginal decoration. Charting the development of the margin (or hāshiyeh) is a significant art-historical challenge, since tactile interaction with the folio edge meant that manuscripts were frequently trimmed and re-margined. This sometimes has important art-historical implications. It is hard, for instance, to determine whether the gold-flecked borders of a Jalayirid Khosrow u Shirin manuscript are the earliest example of this technique by some distance or (more likely) a symptom of Safavid refurbishment.54

In addition, there are several cases where older manuscripts were refurbished and completed, usually through the contribution of missing paintings. Rather than paint directly onto the existing folio, new illustrations were usually executed on a separate piece of paper before being trimmed and pasted into place, often sacrificing the finesse and subtlety with which the painting interacted with the page (see Fig. 4). At other times, the refurbishment of a manuscript went beyond necessary repairs or the insertion of missing components. A well-known example is the 1487 Manteq al-Teyr, which was completely renovated at the instigation of Shah ʿAbbās at the turn of the seventeenth century, with the addition of a sumptuous, contemporary-style frontispiece, fifteen replacement text folios, four illustrations, and new margins throughout in coloured, gold-flecked or marbled paper. Such dramatic reframing suggests that spatially peripheral elements, such as margins and illuminated frontmatter, had come to be seen as powerful visual tools in re-presenting existing paintings, either in a refurbished manuscript or in the context of an album.

However, apart from some fascinating and well-studied exceptions (the miscellanies of Eskandar Soltān and marginal drawings in the Divān of Soltān Ahmad Jalāyir), the borders of Ilkhanid, Jalayirid, and early Timurid paintings were left unadorned.55 Though certain techniques, such as marbling and stencilling, were later innovations, paper dyeing and painted borders were available options if patrons or artists had wished to highlight the marginal field. The blank margin, therefore, can be interpreted as an artistic choice, implying that the matn was understood as the sole visual arena. This makes pictorial eruptions into the margin appear not only to depart from the painted area but to enter an existential void, conveying a greater impression that the image has entered the world of the viewer.

The margin becomes a potential field of artistry from the late fifteenth century. Gold-sprinkled (zarafshāni) margins start to appear in elite, poetic manuscripts from this time, while the sixteenth century saw the introduction of borders painted in gold with floral designs or fantastical forests complete with fighting animals (Fig. 3).56 By the mid-sixteenth century, marbled papers and stencilling (ʿaks) start to appear, still executed in gold on plain or coloured grounds.57 These developments have been described in detail elsewhere, but if the edge of an artwork is taken to comment upon the work within, the effects and interpretation of these borders warrant further consideration.58

Across the diverse techniques and designs already mentioned, it is notable that the margins of Persian manuscripts were always clearly differentiated from the formal qualities of the narrative painting. In Mughal ateliers, by contrast, the margin acquired a much more competitive figural status, filled with illusionistic flowers, animals and even portraits.59 This is, in itself, significant, as Safavid designs positioned the margin not as a competing paratext (or a problematising gloss, as in Camille’s assessment of Gothic marginalia), but as a situating element, an aesthetic context that defines the centre by opposing it.60 The random radiance of a gold-flecked margin, for example, emphasises the intentionality, order, and colour of the narrative painting, while the use of rigid stencils highlighted the miniature’s animation and idiosyncrasies. In the case of manuscripts containing mystical, poetic texts, the gold-flecked borders also imparted a metaphysical atmosphere, like gilded representations of dust—a particularly redolent metaphor in the mystical poetry of ʿAttār.61 By the 1520s, gold-sprinkled paper may have been associated with the admired mystical and didactic manuscripts of Soltān Hoseyn Bāyqarā’s atelier, thereby lending Tahmāsp’s Shāhnāmeh a heightened, supernatural aura, whether in the depiction of mythical divs or legendary battles.

In the case of borders painted with flora and fauna, the visual distinction depends more on their pattern-like arrangement, the open, line-based principle of their designs and their largely monotone palette. These marginal paintings seldom present close thematic links to the paintings they surround, though there are exceptions. In Figure 3, for example, the wild landscape in the margin provides a deliberate contrast with the pastoral scene of Yusof as a herdsman. In the same manuscript, two paintings with stencilled margins both depict themes of discipleship, the follower perhaps aspiring to be the wise man’s ʿaks (reflection).62 More generally, these verdant borders may suggest imaginative richness in the manner of Saʿdi’s metaphor of an orchard (bostān), or evoke the ideal princely landscape for bazm u razm, feasting and fighting. Less often noted is the contrasting, inflated scale of these marginal paintings, which intimates that a miniaturised aesthetic was a valued characteristic of narrative painting.63 Indeed, the often-generous width of the margin also serves to accentuate the concentrated, microcosmic properties of the narrative painting (the full expanse of the gold-flecked margins in the Shāhnāmeh of Shah Tahmāsp is shown in Figure 7).

The margin, then, could speak about the valued aspects of the narrative painting by counterpoint and differentiation, whereas the jadval partook more in the implied superficial materiality of the image. Having focused upon the inward-facing aspects of the edge of Persian painting, however, it is time to consider how an emphasis on the edge speaks to the Safavid world beyond the frame, and to identify some factors that encouraged Tahmāsp’s artists to experiment with the limits and norms of depiction.

IMAGE AS ARTIFICE

In his memoirs, the poet and historian Zayn-al-Din Mahmud Wāsefi relates an incident that occurred at one of the cultural majlises or assemblies of Soltān Hoseyn Bāyqarā, at which the author was a noted riddle-writer and solver.64 The celebrated painter, Behzād, had presented the host, Mir ʿAli Shir Navāyi, with his portrait, surrounded by a beautiful garden. When Mir ʿAli asked his companions to respond to the painting, one replied, ‘when I saw those blossoming flowers, I wanted to stretch out my hand, pick one and stick it in my turban,’ and the next responded in kind, ‘I too had the same desire, but it occurred to me that if I stretched out my hand, all the birds would fly off the trees.’65 This anecdote has caused much art-historical debate over the value and meaning of verisimilitude in Persian art.66 However, it is clear at least that the ontology of the image and the separation between art and reality was an issue that stimulated witty repartee.

The status of painted images was also an essential subject of Safavid album prefaces and other theoretical texts on art that together mark out this cultural moment as particularly analytical and self-reflexive.67 Such texts vociferously celebrate the wonder and power of painting, but also point to an undercurrent of suspicion against images. References to the legendary skill of the prophet-painter Māni, for instance, range from reverent to condemnatory, while the famous hadith of Aisha’s cushion, in which the Prophet Muhammad condemns an image hung on a wall but accepts it in the form of a cushion, could have implied that images on the surfaces of objects were preferred to wall paintings.68

Written sources also present the image as a cerebral construct formulated in ‘the tablet of the heart’ of the painter.69 While the cerebral image is sometimes imagined as being miraculously conferred onto the painted page, at other times it seems to be transferred directly to the mind of the viewer (usually conceived as a receptive mirror), thereby eliding the role of the actual material image. For example, in the preface to the album of Amir Gheyb Beg, Mir Sayyed-Ahmad warns that ‘the beauty that unveils her face in the tablet of the painter’s mind is not reflected in everyone’s imagination.’70 Similarly, in his preface to the Bahrām Mirzā album, Dust Moḥammad describes how the director of Tahmāsp’s ketābkhāneh, Soltān Moḥammad, painted ‘with the pen of his fingertips,’ not on a physical sheet of paper but on the immaterial ‘tablet [lowh] of vision.’71 In this vein, Margaret Graves has recently highlighted the ‘dematerialisation’ of images in the Safavid period and explained the phenomenon in terms of convergent conceptions of optical, cognitive and material images.72 Paradoxically, I would argue that the materiality of the page and the surface-bound nature of the image was paramount in this insubstantial conception of the image. Nevertheless, the manipulation of the pictorial edge expressed the imaginative nature of the image, which submitted to ‘almost no physical constraints.’73

The erudite young Shah would have been familiar with these issues, having grown up in the cultivated centre of Herat. Indeed, on his return to Tabriz, he proceeded to study painting with Soltān Moḥammad and to hold his own majlises.74 In addition, since Tahmāsp’s ketābkhāneh was an amalgamation of Esmāʿil’s Turkman-rooted workshop and artists imported from the Herat school, one can imagine that many subconscious artistic techniques and styles suddenly came into question: the construction of space, the sense of scale, the use of gesture and ornament, the stylisation of landscape elements. Rather than a fumbling attempt to arrive at a unified style, this manuscript should be seen as symptomatic of stylistic self-awareness and a spirit of competitive experimentation with diverse strategies of depiction.

At the centre of this paradigm was a playful interest in the border that divided reality from artifice. Indeed, returning to ‘The Feast of Sadeh’ (Fig. 1), we find that the apparently extraneous and marginal cameos refer, in fact, to the next section of the narrative, in which the king, Hushang, ‘used his God-given royal authority to separate animals into those that are wild and can be hunted, like onager and deer, and those suitable for domestic use, like cows, sheep and donkeys.’75 Looking again, we see that the golden frame is enacting Hushang’s division between the domain of human control and creativity within, and the wilderness without. The golden rulings embody the god-like powers of the artist, and his ability to define both the scope and limits of the painted image. Framing the image was a fundamental aspect of Persian pictorial practice, and while the treatment of the pictorial boundary in Persian paintings could often be conventional and standardised, this analysis of the Shah Tahmāsp Shāhnāmeh shows that imaginative and meaningful manipulations of the edge were hallmarks of an intellectualised form of artistic prowess, and reveals a nuanced Safavid understanding of the image as both material surface and imaginative artifice.

Citations

[1] Leon Battista Alberti, On Painting, ed. Martin Kemp, trans. Cecil Grayson (London: Penguin Books, 1991), 54.

[2] Jacques Derrida, The Truth in Painting, trans. Geoffrey Bennington and Ian MacLeod (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 61.

[3] This article follows the Iranian Studies transliteration scheme for Persian words, except for familiar terms such as ‘Shah.’ The transliteration of quoted scholarship or academic book titles, however, has not been altered.

[4] Martin Bernard Dickson and Stuart Cary Welch, The Houghton Shāhnāmeh (Cambridge, Mass.: Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, 1981), 4. For a summary of the manuscript’s tragic dismemberment by Arthur Houghton Jnr, see Burzine Waghmar, ‘An Annotated Micro-history and Bibliography of the Houghton Shahnama,’ in Firdawsi Millennium Indicum: Proceedings of the Shahnama Millenary Seminar, eds S. Sharma and B. Waghmar (Mumbai: K. R. Cama Oriental Institute, 2016), 144-180.

[5] Dickson and Welch, The Houghton Shāhnāmeh, 45.

[6] Robert Hillenbrand, ‘The Iconography of the Shah-Namah-Yi Shahi,’ in Safavid Persia: The History and Politics of an Islamic Society, Pembroke Papers 4, ed. C. P. Melville (London: I.B. Tauris, 1996), 53-78. Prior to the Dickson and Welch two-volume facsimile, Welch edited a condensed version and an exhibition catalogue for the newly dispersed folios: Stuart Cary Welch, A King’s Book of Kings: The Shah-Nameh of Shah Tahmasp (New York: The Metropolitan Museum, 1972); Stuart Cary Welch, Wonders of the Age: Masterpieces of Early Safavid Painting, 1501-1576 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Art Museums, 1979), 14-27. Since then, Sheila Canby has written most frequently on the manuscript, in both surveys of Safavid art and in the 2014, reduced-size facsimile. Canby generally recapitulates the Welch and Dickson narrative, though adding more historical context, and exploring how the paintings depict the rich material world of Shah Tahmāsp: Sheila Canby, The Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp, (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014); Sheila Canby, The Golden Age of Persian Art, 1501-1722(London: British Museum Press, 1999), 34, 50-54; Sheila Canby, ‘Safavid Painting,’ in Hunt for Paradise: Court Arts of Safavid Iran, 1501-1576, eds J. Thompson and S. Canby (Milan: Skira, 2003), 73, 82-84. Eleanor Sims also comments on the manuscript’s ‘wildly uneven pictorial quality’: Eleanor Sims, Peerless Images: Persian Painting and its Sources (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 63-64. Although individual paintings are discussed more frequently, this limited bibliography shows that this astonishing monument of Safavid painting is ripe for more focused interpretative and theoretical analysis.

[7] The description of a ‘classical’ style of Persian painting is problematic, but acknowledges the canonical status of Shah Tahmāsp’s atelier; for a critique see Christiane J. Gruber, ‘Questioning the ‘Classical’ in Persian Painting: Models and Problems of Definition,’ Journal of Art Historiography 6 (2012): 1–25.

[8] Victor Ieronim Stoichiță, The Self-Aware Image: An Insight into Early Modern Meta-Painting, Cambridge Studies in New Art History and Criticism (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 30.

[9] Werner Wolf and Walter Bernhart, eds, Framing Borders in Literature and Other Media (Leiden: Brill, 2006), 5, 7.

[10] Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgement, ed. Nicholas Walker, trans. James Creed Meredith, reissued, Oxford World’s Classics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 57.

[11] Michael Camille, Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992), 154.

[12] Stoichiță, Self-Aware Image, 4.

[13] Otto Pacht, The Master of Mary of Burgundy (London: Faber and Faber, 1947), 25.

[14] Dickson and Welch, The Houghton Shāhnāmeh, 25.

[15] Dickson and Welch, 45; Priscilla Soucek and Muhammad Isa Waley, ‘The Nizāmi Manuscript of Shāh Tahmāsp: A Reconstructed History,’ in A Key to the Treasure of the Hakīm: Artistic and Humanistic Aspects of Nizāmī Ganjavī’s Khamsa, eds J. C. Bürgel and C. van Ruymbeke (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2011), 195-210.

[16] Sheila Canby, for instance, follows Dickson and Welch’s theory of a ‘Safavid synthesis’ in Sheila R. Canby, Persian Painting (London: British Museum Press, 1993), 76, 82.

[17] Elaine Wright, Muraqqaʿ: Imperial Mughal Albums from the Chester Beatty Library (Alexandria, Va: Art Services International, 2008).

[18] Exceptions being: (i) Chahryar Adle, who makes the width of the jadval the basis of his ‘modular’ analysis of late sixteenth century painting, though this approach does not transfer neatly to earlier, thinner jadval design: Chahryar Adle, ‘Recherche sur le Module et le Tracé Correcteur,’ Le Monde Iranien et l’Islam 3 (1975): 81–105; (ii) Yves Porter, Painters, Paintings and Books: An Essay on Indo-Persian Technical Literature, 12-19th Centuries, trans. S Butani (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2021), 59–61, (iii) Sheila S. Blair, ‘Color and Gold: The Decorated Papers Used in Manuscripts in Later Islamic Times,’ Muqarnas 17 (2000): 28–29.

[19] Wright, Muraqqaʿ, 40.

[20] Blair, ‘Color and Gold,’ 28.

[21] Dated ca 1430-1435, MS. Ouseley Add. 176, Bodleian Library, Oxford.

[22] Marianna Shreve Simpson, Sultan Ibrahim Mirza’s ‘Haft Awrang’: A Princely Manuscript from Sixteenth-Century Iran (New Haven: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Yale University Press, 1997), 63.

[23] Paintings from Add. 25900 that are not illustrated are available both on the British Library website and in Barbara Brend, Treasures of Herat: Two Manuscripts of the Khamsah of Nizami in the British Library (London: Gingko, 2022).

[24] Qāzi Ahmad, Calligraphers and Painters: A Treatise by Qadi Ahmad, Son of Mir-Munshi, trans. V. Minorsky, Freer Gallery of Art Occasional Papers (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1959), 189.

[25] Qāzi Ahmad, 195–96.

[26] Qāzi Ahmad, 195.

[27] Robert Hillenbrand, ‘The Uses of Space in Timurid Painting,’ in Timurid Art and Culture: Iran and Central Asia in the Fifteenth Century, eds L. Golombek and M. Subtelny (Leiden: Brill, 1992), 84–92; Blair, ‘Color and Gold,’ 28–29.

[28] Hillenbrand, ‘Uses of Space in Timurid Painting,’ 84.

[29] Blair, ‘Color and Gold,’ 28–29.

[30] Blair, 29.

[31] Hillenbrand, ‘Uses of Space in Timurid Painting,’ 78.

[32] Hillenbrand, 84.

[33] Blair, ‘Color and Gold,’ 29.

[34] Rachel Milstein, ‘Persian Painting: The Page and the Text as Determinants in the Construction of Pictorial Space,’ Studies in Honour of Ella Landau-Tasseron, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 49 (2020): 313-356.

[35] MS. 716, Gulistan Palace Museum, Tehran. High quality images from this manuscript are hard to access, but relevant paintings are ‘Jamshid Teaches the Crafts’ (f. 31), ‘Fereydun Nails Zahhāk on Mount Damāvand’ (f. 40) and ‘Rostam and the White Div’ (f. 101).

[36] O’Kane has explored the notable pictorial margins of the famous 1370 Kalileh va Demneh fragments: Bernard O’Kane, Early Persian Painting: Kalila and Dimna Manuscripts of the Late Fourteenth Century (London: I.B. Tauris, 2003) 238-239. Brend provides a general survey of narrative uses of the margin up to the Safavid period: Barbara Brend, ‘Beyond the Pale: Meaning in the Margin,’ in Persian painting: from the Mongols to the Qajars, ed. R. Hillenbrand (London: I. B. Tauris, 2000), 39-53.

[37] Julie Scott Meisami, ‘Palaces and Paradises: Palace Description in Medieval Persian Poetry,’ in Islamic Art and Literature, eds O. Grabar and C. Robinson (Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2001), 21-24.

[38] Translation by Leili Vatani and the author of the architectural inscription in ‘The Wrestling Match’ from Prince Bāysonghor’s Golestān of Saʿdi, 1427, Per 119.14, Chester Beatty Library, Dublin.

[39] Adle, ‘Recherche sur le Module et le Tracé Correcteur,’ 91.

[40] Hillenbrand, ‘Uses of Space in Timurid Painting,’ 91; Chad Kia, ‘Is the Bearded Man Drowning? Picturing the Figurative in a Late- Fifteenth-Century Painting from Herat,’ Muqarnas 23 (2006): 87-90; Rachel Milstein, ‘Sufi Elements in the Late Fifteenth-Century Painting of Herat,’ in Studies in Memory of Gaston Wiet, ed. M. Rosen-Ayalon (Jerusalem: Institute of Asian and African Studies, Hebrew University, 1977), 363.

[41] Brend, ‘Beyond the Pale,’ 47.

[42] Marianna Shreve Simpson, Princeton’s Great Persian Book of Kings: the Peck Shahnama (Princeton: Princeton University Art Museum, 2015).

[43] Per 270, Chester Beatty Library, Dublin.

[44] Dickson and Welch, The Houghton Shāhnāmeh, 43.

[45] This dense sequence of illustrations includes seven paintings, from f. 341v to f. 346r, all of which belong to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (1970.301.43-46) except for the painting of the first joust, see Note 47.

[46] ‘The Sixth Joust of the Rooks: Bizhan Versus Ruyyin,’ f. 343r. 1970.301.44, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

[47] ‘The First Joust of the Rooks: Fariburz Versus Kalbad,’ AKM497, The Aga Khan Museum, Toronto.

[48] MS 41.2007, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha.

[49] AKM165, The Aga Khan Museum, Toronto.

[50] I am grateful for being pointed to the blood spatter in the painting ‘Bahrām Gur Fights the Horned Wolf’ from the Great Mongol Shāhnāmeh, (Harvard Art Museums) which also shows a blood spatter escaping the pictorial field. Very close observation, however, shows that the jadval lines around this painting have been ruled on top of this detail and so this instance seems less indicative of a self-conscious experimentation with the pictorial edge.

[51] Attrib. Mirza Ali, ‘Nushirvān Receives an Embassy from the Raja of Hind,’ f. 638a from theShāhnāmeh of Shah Tahmāsp, ca 1525 – 1530. Ebrahimi Family Collection on loan to the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

[52] Rod A. Martin, The Psychology of Humor: An Integrative Approach (Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press, 2007), 5.

[53] Martin, 6.

[54] F1931.29-37, National Museum of Asian Art, Washington.

[55] On Eskandar Soltān anthologies: David J. Roxburgh, ‘The Aesthetics of Aggregation: Persian Anthologies of the Fifteenth Century,’ in Islamic Art and Literature, eds O. Grabar and C. Robinson (Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2001); Priscilla Soucek, ‘The Manuscripts of Iskandar Sultan: Structure and Content,’ in Timurid Art and Culture: Iran and Central Asia in the Fifteenth Century, eds L. Golombek and M. Subtelny (Leiden: Brill, 1992), 122-124. On the Soltān Aḥmad’s Divān, see Ilse Sturkenboom, ‘The Paintings of the Freer Divan of Sultan Ahmad b. Shaykh Uvays and a New Taste for Decorative Design,’ Iran 56, no. 2 (2018): 184–214; Robert Hillenbrand, ‘The Uses of Space in Timurid Painting,’ 77–102.

[56] Blair, ‘Color and Gold,’ 30–31. Norah M. Titley, Persian Miniature Painting and Its Influence on the Arts of Turkey and India: The British Library Collections (London: British Library, 1983), 223–26; O. F. Akimushin and Anatol Ivanov, ‘The Art of Illumination,’ in The Arts of the Book in Central Asia, 14th-16th Centuries, eds O. F. Akimushin and Basil Gray (London: Serindia Publications, 1979), 48–49.

[57] The term ʿaks is given in Porter, Painters, Paintings and Books, 51-52.

[58] Primarily in Porter, Painters, Paintings and Books, 36-53 and Titley, Persian Miniature Painting, 224-228.

[59] Marie Lukens Swietochowski, ‘Decorative Borders in Mughal Albums,’ in The Emperors’ Album: Images of Mughal India (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987), 45-78.

[60] Camille, Image on the Edge, 10, 20-22. For the seminal articulation of the paratext, see Gérard Genette, Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

[61] See, for example, beyts 152-158 and 190-193 in the prologue to Manteq al-Teyr, in Farid-od-Din ʿAttār, The Canticle of the Birds, trans. Afkham Darbandi and Dick Davis (Paris: Diane de Selliers, 2013), 66, 68.

[62] On this and other interesting instances of marginal decoration in Ebrāhim Mirzā’s Haft Owrang, see Simpson, Sultan Ibrahim Mirza’s ‘Haft Awrang,’ 64–66, 130.

[63] A question addressed in detail by the author’s PhD research, but also noted by other scholars, primarily Roxburgh’s important article identifying a ‘quest for minuteness’ in Persian painting and the centrality of pictorial complexity: David J. Roxburgh, ‘Micrographia: Toward a Visual Logic of Persianate Painting,’ RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 43 (2003): 27–29.

[64] Keith Hitchins, ‘Wāṣefi, Zayn-al-Din Maḥmud,’ in Encyclopædia Iranica, 2016.

[65] Quoted and discussed in Lamia Balafrej, The Making of the Artist in Late Timurid Painting, Edinburgh Studies in Islamic Art (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019), 99.

[66] Roxburgh, for example, points both to the rhetorical structure of the exchange and the celebration of an image without recourse to ordinary devices of naturalism. See David J. Roxburgh, ‘Kamal al-Din Bihzad and Authorship in Persianate Painting,’ Muqarnas 17 (2000): 122.

[67] David Roxburgh, Prefacing the Image: The Writing of Art History in Sixteenth-Century Iran (Leiden: Brill, 2001). For the primary texts, see Wheeler M. Thackston, ed., Album Prefaces and Other Documents on the History of Calligraphers and Painters (Leiden: Brill, 2014). For Safavid theorizing literature on art, see Yves Porter, ‘From the “Theory of the Two Qalams” to the “Seven Principles of Painting”: Theory, Terminology and Practice in Persian Classical Painting,’ Muqarnas 17, no. 1 (2000): 109–18.

[68] However, the interpretation of this hadith is complex and contentious, see Jamal J. Elias, Aisha’s Cushion: Religious Art, Perception, and Practice in Islam (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2012). For the varied representations of Māni in Persian literature, see Priscilla P. Soucek, ‘Nizami on Painters,’ in Islamic Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, ed. R. Ettinghausen (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1972), 9–10.

[69] Khvandamir, from the preface to ‘An Album made by Kamaluddin Bihzad,’ in Thackston, Album Prefaces and Other Documents on the History of Calligraphers and Painters, 42.

[70] Mir Sayyed-Ahmad, ‘Preface to the Amir Gheyb Beg Album,’ in Thackston, 26.

[71] Dust Mohammad, ‘Preface to the Bahram Mirza Album,’ in Thackston, 16. Soucek has noted the cerebral nature of images as they are presented in Nezāmi’s Khamseh: Soucek, ‘Nizami on Painters,’ 12.

[72] Margaret Graves, ‘Painting of a Painting and a Boy on a Bottle: Thresholds of Image in Early Modern Iran,’ in The Routledge Companion to Global Renaissance Art, eds Stephen J. Campbell and Stephanie Porras (New York: Routledge, 2024), 414.

[73] Graves, 424.

[74] Described as ‘paradisiacal assemblies’ by the calligrapher Mir Sayyed-Ahmad in his album preface to Amir Gheyb Beg Album, in Thackston, 28.

[75] Abul-Qāsem Ferdowsi, Shāhnāmeh: The Persian Book of Kings, trans. Dick Davis (London: Penguin Books, 2006), 4.