On the morning of 1 November 1755, All Saints Day, the inhabitants of Lisbon, Portugal experienced one of the most significant seismic events in recorded history. Three separate shocks hit the city, raising an enormous cloud of dust and triggering massive waves which swept up the mouth of the River Tagus, washing away many initial survivors.1 The city then caught fire, partially due to the multitude of candles which had filled Lisbon’s now-ruined churches for All Saints Day services.2 In the ensuing months, reports of this disaster circulated globally in letters, pamphlets, and newsprint as people sought to make sense of the calamity. In the process, the Lisbon earthquake became a defining event in Enlightenment thought, provoking responses from the likes of Voltaire and Rousseau that grappled with human mortality and the concept of divine will.3 To this day, scholars and scientists from a myriad of disciplines continue to study this moment in history to better understand its extensive impact across the Atlantic world.

In her discussion of John Singleton Copley’s trans-Atlantic career of the 1760s, Jennifer Roberts argues for the importance of putting the distance back into historical analysis of the circum-Atlantic sphere. Although we now possess ‘the historian’s twin powers of hindsight and overview,’ we must remember that ‘objects should not leave one side of the Atlantic and bob up immediately on the other as if beamed there by satellite.’4 In studies of material and intellectual exchange across the eighteenth-century Atlantic, this caveat undoubtedly holds true. However, an event like the Lisbon earthquake complicates Roberts’ analysis. In the months and years following the quake, locations across the Atlantic world reported a variety of unusual phenomena that took place on 1 November 1755. Sites as far-ranging as the Caribbean island of Antigua and Newfoundland, Canada recorded abnormal waves and other strange movements of the ocean.5 At the time, people would have taken these for mysterious, isolated incidents. However, modern science allows us to explain these events in their greater context. In 2021, researchers at the Institut de Ciències del Mar in Barcelona recreated the Lisbon earthquake via digital seismic modelling, demonstrating that the earthquake’s shock reverberated across the entire Atlantic Ocean.6 The resulting waves, measuring up to five metres in height in some places, would have reached the Atlantic coasts of North and South America between six and ten hours after the earthquake.7 In an age when any communication one wanted to send across the Atlantic took weeks to arrive, the idea that a tangible phenomenon emanating directly from one side of the ocean could reach the other in a matter of hours was an astonishing concept. However, the delay in receiving the information necessary to situate that phenomenon within broader knowledge and lived experience remained firmly defined by eighteenth-century maritime technology’s limits. It is remarkable that the Lisbon earthquake’s seismic waves managed, if only for a few hours, to exceed the otherwise-insurmountable temporal and physical limitations of the eighteenth-century Atlantic Ocean.

This article deals with printed images of three earthquakes originating from different corners of the Atlantic world, progressing from Jamaica to New England and finally to Lisbon itself. In no ways an exhaustive list, these examples illustrate the challenges that people faced, the techniques they utilised, and the stories they prioritised while attempting to replicate seismic events on paper. Though this subject has certainly been rendered in media beyond print, here I limit my inquiry to print sources due to their mobility and relevance to circum-Atlantic exchange.

RESISTING THE VISUAL

Regarding the history of earthquakes, the textual record by far outweighs the visual. Because of earthquake studies’ historical reliance on oral accounts and their subsequent transcriptions, people conceived of earthquakes and sought explanations for them via the study of ancient philosophical texts, as will be discussed below.8 Another reason for this imbalance is intuitive: earthquakes fundamentally resist visual format. As Susanne Keller writes:

Earthquakes (unlike volcanoes) are phenomena that largely evade pictorial representation. Their principal characteristics are their sudden occurrence and their unpredictability. Because they usually pass in a few minutes, they cannot actually be observed, let alone recorded in drawings or studies on the spot. The natural force itself remains invisible.9

Though early modern artworks certainly dealt with natural disaster, from scenes of biblical deluge to volcanoes, these subgenres each had accompanying, clearly prescribed elemental actors: fire and water. Conversely, as durational events caused by unseen forces, earthquakes are not easily captured within the bounds of a static image. Keller references a quote by Oxford scientist Charles Daubeny (1795-1867) which provides insight into the state of earthquake studies in the early nineteenth century. In 1826, Daubeny voiced his frustrations about the field, writing that ‘the processes [of earthquakes] … are placed beyond the scope of actual observation, and can be conjectured solely from certain of their remote consequences.’10 As Daubney describes, man’s inability to peel back the earth’s surface and directly observe the machinations below meant that seismic phenomena could only be observed via their symptoms. However, even these ‘remote consequences’ (disturbances in bodies of water, strange odours, et cetera) required observation to verify. This emphasis on the observer’s role in the creation of seismic activity echoes a phrase published in the Derby Mercury in January of 1756. At a remove of several months from the Lisbon earthquake, the Mercury took stock of the information that had circulated since. Considering the variety of reported phenomena, the paper’s editors wrote that ‘probably other Lakes or large Pieces of Water in this Kingdom were agitated as well … but wanted an Observer.’11 Without a human witness who could accurately describe their experiences to others, seismic phenomena were rendered non-existent. After all, in a time in which the surface of the earth formed an impenetrable veil obscuring the natural workings within, observation was reality. While severe seismic events might leave behind physical traces for people to discover later, it was entirely possible for weaker events to come and go without notice if they lacked an audience.

CIRCUM-ATLANTIC EARTHQUAKES

Methodologically, I propose the consideration of earthquakes as a connective phenomenon within the circum-Atlantic sphere, one which both prompted and required people to communicate as they sought answers to their fears of the unknown. Conceptions of the ocean as a causal factor in seismic activity had existed for thousands of years since Aristotle and philosophers after him identified that coastal areas, mountainous regions, and islands close to shore experienced earthquakes at a higher rate than other terrains.12 Believing that earthquakes occurred due to the rushing of air within subterranean cavities, these early thinkers recognised that littoral zones facilitated the necessary meetings of earth, wind, and water that produced such a reaction. Though the Lisbon earthquake is often cited as the impetus for modern seismology, earthquake studies would feel the influence of these ancient sources well into the nineteenth century. In 1760, John Michell (1724-1793), today regarded as a seminal figure in the study of earthquakes, asserted that ‘the most extensive earthquakes frequently take their rise from the sea.’13 This is not to say that the field of earthquake studies had remained static since Aristotelian times; in fact, by the eighteenth century, Aristotle’s concept of underground winds had given way to ideas about combustible vapours within the earth.14 However, coastal zones continued to experience frequent earthquakes, demonstrating that, at least in some respects, the ancients must have been on the right track. Proximity to the ocean, the very thing that advantaged Atlantic societies through the trade and connection it brought, could also expose them to mutual seismic peril. Though not every earthquake made literal or metaphorical waves on the scale of Lisbon, earthquakes as a concept remained a looming, unexplained threat which the ocean had the power to amplify.

Joseph Roach’s ideas about circum-Atlantic performance and memory offer additional insight into the transmission of earthquake imagery during this era, particularly his concept of surrogation. Surrogation, or ‘the doomed search for originals by continuously auditioning stand-ins,’ refers to the way that circum-Atlantic societies sought to fill gaps in their social fabric owing to the impossibility of simultaneous presence on both sides of the ocean. This persistence in the face of futility echoes how people continued to render earthquakes in visual media despite the subject’s fundamental pictorial resistance.15 In an age before film and photography, oral accounts, textual transcriptions, and artistic interpretations remained the only formats through which people could perceive and record seismic activity (save for personally living through an earthquake). Although these second-hand records encapsulated neither the visceral sensation of earthquakes nor the knowledge of what caused them, people continued to produce them, desperate to gain some insight or feeling of commonality that might assuage their seismic fears. Often, these documents use workarounds such as moral and religious metaphors, substituting more easily comprehensible narratives about good and evil, harmony and discord to approximate people’s unsettling seismic experiences. In the eighteenth-century Atlantic world, visualising seismic events meant combatting both the pictorial resistance of earthquakes and the unavoidable barrier of Atlantic distance and delay, often simultaneously.

The examples that follow lie at uneven chronological intervals because the two influencing factors this article considers—Atlantic distance and delay and the pictorial resistance of earthquakes—did not change significantly during this period. Lacking a comprehensive explanation for seismic activity and still generations away from technology that would significantly reduce the duration of Atlantic transit, inhabitants of the Atlantic sphere dealt with these issues over the entirety of the long eighteenth century.

THE PORT ROYAL EARTHQUAKE (1692)

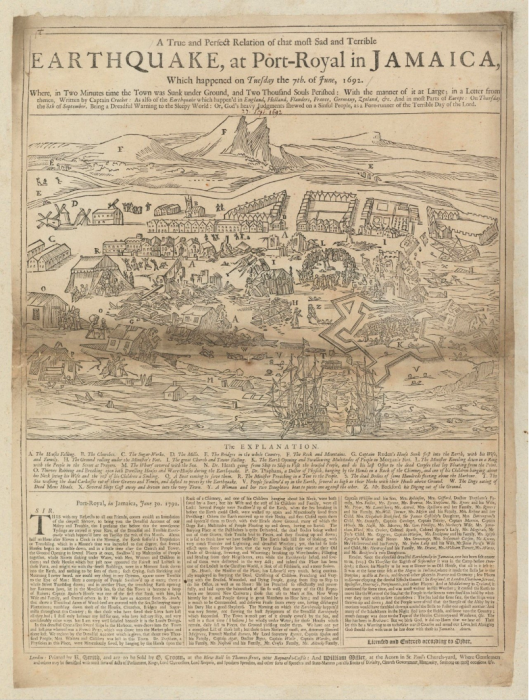

Published over sixty years prior to Lisbon’s devastation, the first visualisation of an Atlantic earthquake this article considers appeared on a London broadside in September 1692: ‘A True and Perfect Relation of that most Sad and Terrible Earthquake, at Port-Royal in Jamaica’ (1692, Fig. 1). A few months earlier on the morning of 7 June, an earthquake destroyed the majority of Port Royal, rendering it uninhabitable. Located at the entrance to a deep-water harbour, Port Royal historically functioned as a critical Atlantic port within both English and Spanish colonial networks.16 Situated at the end of a long, spit-like peninsula, it remained under Spanish rule from the late fifteenth century until the British took it over in the 1650s. By the time of the earthquake, it had grown into one of British America’s most important and populous settlements, in the process developing a reputation for piracy, crime, and otherwise-immoral behaviour.17 Indeed, the broadside describes Port Royal as ‘one of the Ludest [places] in the Christian World, a Sink of all Filthiness, and a meer Sodom.’18

The broadside woodcut presents a bird’s-eye view of Port Royal, much of it in ruins. The foreground shows the city’s harbour overflowing its bounds, partially submerged buildings and human bodies swirling in the powerful current. Two ships in the centre of the composition reference the city’s status as a port. Onboard one of these vessels, a man stands at the same height as the ship’s hull, demonstrating the broadside’s manipulation of scale. The middle ground shows the city in chaos, activity occurring in every corner. The document’s alphabetised legend helps viewers identify moments such as ‘The Earth Opening and Swallowing Multitudes of People in Morgan’s Fort’ or ‘Thieves Robbing and Breaking open both Dwelling Houses and Ware-Houses during the Earthquake.’19 Along the image’s right-hand border, boundaries between land and sea dissolve as waves overtake the city. Behind Port Royal, an almost diagrammatic landscape references the damage inflicted on other parts of Jamaica. Amongst a few mountains and hills, empty roads and bridges connect Port Royal to other, unseen locations.

The broadside’s textual content comes from letters sent by an unknown author named ‘Captain Crocket’ and from the publisher’s commentary about another recent earthquake felt throughout England and continental Europe.20 This comparative approach features often in early modern earthquake texts as people sought to consolidate narrative accounts and identify their similarities.21 In this way, the common plight of seismic disaster could unite even the most disparate of regions. However, the compilation of two or more earthquake narratives could also highlight discrepancies between events, in the process reflecting narrators’ biases. For instance, the Port Royal broadside concludes with the admonishment ‘let this be a Warning to us to forsake our ill Courses and mend our Lives, lest Almighty God should deal with us as he has done with those inJamaica.’22 To those in London gazing back across the Atlantic at their colonial counterparts, the Port Royal earthquake presented an opportunity to define metropolitan British morality against the depravity of known sinners who had clearly suffered the consequences of their actions.

Within the woodcut, every stage of the earthquake occurs simultaneously, townspeople attempting to dig each other out of the ground while shattered buildings still hang frozen in mid-air above them. This use of continuous narrative becomes increasingly noticeable when tracing the movements of one of this story’s protagonists, Reverend Emmanuel Heath (fl. 1692). Heath, Port Royal’s Anglican minister (and the aforementioned oversized figure aboard a ship), makes no fewer than four simultaneous appearances within the broadside: ‘H. The Ground rolling under the Minister’s Feet;’ ‘L. The Minister Kneeling down in a Ring with the People in the Street at Prayers;’ ‘N. Dr. Heath going from Ship to Ship to Visit the bruised People…;’ and, ‘R. The Minister Preaching in a Tent to the People.’23 The broadside paints a flattering picture of Heath, describing how he ‘has Labour’d very much’ in tending to the city’s population. He also ‘has Preached so effectually and powerfully, and laid open the hainousness of Sin so well, that many of the Old Reprobates are become New Converts’ in the earthquake’s aftermath.’24 By this account, Heath not only combats the community’s suffering inflicted by the earthquake, but also the pervasive debauchery of Port Royal’s populace.

In a word, the Port Royal broadside is crowded, obliging all relevant visual information to fit within the picture plane. In this context, the image’s symbolic elements take precedence over naturalism, resulting in the distortion of physical scale and the abbreviation of space and time. These stylistic qualities derive at least in part from the way woodcut broadsides were consumed by the public. Margaret J. M. Ezell has helped to draw attention to the fact that ‘the early modern world was an oral and acoustic one.’25 In the late seventeenth century, the majority of London’s population was illiterate or semi-literate, meaning that illustrated broadsides such as this one needed to cater to ‘multiple levels of literacy through the employment of multiple modes of reading.’26 Depending on their literacy levels or preferences, broadside consumers could take in information via image, text, or a combination of the two. Furthermore, the reading aloud of broadsides in public spaces could add another modality to these documents.

Applied to the Port Royal document, Ezell’s ideas about the semiotics of early modern broadsides suggest that it was Crocket’s text, and not a map or visual diagram, that served as the basis for the woodcut. For example, the image contains a structure labelled as ‘Morgan’s Fort,’ a polygonal form widely understood to represent a defensive construction. However, historical plans of Port Royal more often refer to this structure as Morgan’s Line, which as its name suggests was not an enclosed fortification, but a fortified wall.27 The angular outline of a fort, while inaccurate in the context of Port Royal, does conveniently function as a graphic sign easily comprehensible to early modern Londoners. Its simplicity and semiotic legibility help activate the document’s multimodality, giving viewers an easier alternative than searching for the tiny ‘K’ labelling pertinent explanatory text. A similar divergence appears in the woodcut’s landscape background. Though Port Royal sat at the end of a peninsula, a considerable stretch of water separating it from mainland Jamaica, the broadside reduces this substantial harbour into a miniscule river. In both cases, the semiotic requirements of broadside imagery render the reality of Port Royal irrelevant. Even if those who produced the woodcut did possess knowledge of Port Royal’s geography, the need to provide a diagrammatic visual aid for the broadside’s text outweighed any impulse towards faithful reproduction of the city.

By 1690, the population of Port Royal numbered 6,500 individuals, just over half of which—around 3,900—were white. The rest constituted mostly enslaved Africans and their descendants, a few free people of colour, and even fewer Indigenous Americans brought to the island from elsewhere.28 However, the broadside decidedly focuses on how the earthquake has affected Port Royal’s ruling elite. When reporting the earthquake’s casualties, Crocket clarifies that, while not yet complete, his list contains the names of ‘those taken Notice of most.’29 What follows are the names of government officials, bureaucrats, and military officers, all people who held prominent positions in the community. One can only infer the disaster’s impact on Port Royal’s enslaved population via a sentence describing the destruction of buildings. These included ‘many Plantations’ and ‘most of the Houses, Churches, Bridges and Sugar-mills throughout this Country.’ As a result, ‘those who have saved their Lives have lost all they had.’30 In all, between one and two thousand people died during the Port Royal earthquake.31 However, we can assume that Port Royal’s enslavers would have counted their supposed human property as lost assets rather than human casualties.

Though this article discusses the transmission of printed images—and by extension the printed word—within the Atlantic sphere, Julius S. Scott has rightly pointed out that ‘books, newspapers, and letters which arrived with the ships were not the only avenues for the flow of information and news in Afro-America.’32 Oral networks of communication created and sustained essential connections, particularly within enslaved communities whose members were actively barred from achieving literacy. However, these networks and their participants were rarely valued or ‘taken Notice of’ by colonial authorities, resulting in their absence from the dominant historical record.33 Though documents like the Port Royal broadside certainly helped make goings-on in the larger Atlantic world visible to a European audience, viewers must also consider the perspectives these images may omit.

THE CAPE ANN EARTHQUAKE (1755)

The next earthquake image this article considers and the circumstances surrounding it demonstrate the Atlantic Ocean’s function as, in Jennifer Roberts’ words, ‘a temporal scrambling agent.’34 On the morning of 18 November 1755, residents of Boston and surrounding areas awoke before dawn to the sensation of the earth shaking. Retroactively named due to its estimated epicentre off Cape Ann to the northeast of Boston, the Cape Ann earthquake remains one of the largest seismic events recorded in the north-eastern United States.35 In its wake, the people of Boston witnessed a prodigious output of sermons, pamphlets, and broadsides, all offering interpretations of the earthquake.36 Then, only a few weeks later, reports of what had befallen Lisbon on 1 November appeared in American newspapers on 8 December 1755.37 Immediately after the Cape Ann event, Bostonians had found themselves at the centre of a story with potentially immense theological consequences. However, the news from Lisbon displaced Boston within this narrative, forcing all those who had put forth their opinions to accommodate new information. In this case, the Atlantic Ocean’s temporally scrambling properties reversed the chronology of Lisbon and Cape Ann in the minds of New Englanders, adding further confusion to an already chaotic sequence of events.

A broadside sold by Boston printer John Green (1731-1787) titled ‘Earthquakes improved: or Solemn warning to the world’ features a woodcut image inset above a forty-stanza poem (1755, Fig. 2).38 Because it focuses solely on the Cape Ann event, it seems that ‘Earthquakes improved’ was published in the twenty days between 18 November and 8 December 1755. In contrast, the overwhelming majority of sources produced after 8 December compare the two earthquakes. Whitney Barlow Robles has discussed how these slightly later comparative sources ‘begged New Englanders to heed God’s warning while also recasting the Cape Ann earthquake as less of a disaster than initially thought.’39 One stanza of ‘Earthquakes improved’ reads ‘Love not this World where Nothing fixt / But all Things tott’ring are: / You and your Idols shall be burnt / In one devouring Fire.’40 These lines exemplify tendencies in Christian earthquake commentaries to employ metaphorical language evoking the physical effects of earthquakes (‘tott’ring’). The fact that ‘Earthquakes improved’ draws on this kind of language without explicitly mentioning Lisbon also seems a clear indicator that its producers remained ignorant of the larger earthquake. After all, Vermij points out that, in the eyes of Protestant ministers, ‘Interpretations that appeared to support their own view of the world or the position of the church were hard to reject.’41 The mention of idols devoured by fire creates a chilling, almost prophetic parallel to the Lisbon disaster, during which the city’s (Catholic) churches burned to the ground. Though perhaps not meant as a specific reference to Lisbon, this excerpt suggests how the people of New England may have framed the events of 1 November once they did hear the news, mindful of the divisions between Protestant New England and Catholic Iberia.

While the Cape Ann broadside does address broader theological implications of the earthquake, it also speaks to the specific lived experiences of New Englanders. It shows not a conceptual earthquake which could happen anywhere, but an earthquake centred on Boston and its population. The image’s open foreground contains several people reacting to the earthquake, some falling on their knees with hands clasped in prayer or extended in supplication. Others gesture upwards towards the sky, equally astounded. Around them, ridges in the earth suggest cracks forming, or else movement underfoot. In the middle ground, clusters of buildings overlap in an almost abstracted collage, their angled walls and tilted roofs implying the earth’s upheaval. Right of centre, a church with its conic steeple knocked askew has lost its weathervane, a double-pointed swallowtail that hurtles towards the ground. Overhead, a glowing moon shines down through a dark, partially cloudy sky punctuated by stars. Juxtaposed against this celestial backdrop, the falling weathervane takes on the appearance of a heavenly body in motion.

‘Earthquakes improved’ stands out from other printed material created in response to the Cape Ann event and from the visual archive of earthquakes as a whole. Often, historical earthquake images possess geographic or temporal separation from the events they describe. In large part, this is because following a devastating earthquake, communities understandably deprioritised artistic expression to fulfil more basic needs. However, the Cape Ann event, significant enough to merit recording but minor enough to avoid largescale destruction, allowed Boston and surrounding areas to retain the capacity for creative response. Thus, ‘Earthquakes improved’ employs visual communication at a pace which begins to approach that of textual exchanges around earthquakes in the eighteenth century.

The text of ‘Earthquakes improved’ echoes the geographical specificity of its image. One stanza reads ‘Say, Travellers through Scituate, / What Breaches fright your Eye! / Where the new Fountain bubbles up, / And Loads of Ashes lye!’42 This coincides with the first-hand account of Harvard mathematician John Winthrop (1714-1779) published in 1757 by the Royal Society in London. Winthrop states that at Scituate, Massachusetts, to the south of Boston Harbor, ‘there were several chasms or openings made in the earth, from some of which water has issued, and many cart-loads of a fine whitish sort of sand.’43 Another stanza of ‘Earthquakes improved’ situates the Cape Ann event within the history of Atlantic earthquakes. Recounting past seismic disasters, the poem describes how ‘Sometimes Men have been buried whole, / Sometimes been sunk half Way, / Where they have been devour’d by Dogs, / And Birds and Beasts of Prey.’44 This episode stems directly from the Port Royal earthquake over sixty years prior, as a tiny vignette of ‘The Dogs eating of Dead Mens Heads’ appears near the central fold of the Port Royal broadside (Fig. 1).45 The concept of dogs turning on humankind, an image so at odds with traditional ideas of canine fidelity, mirrors sentiments in other stanzas where the world falls into disorder, a narrative and pictorial trope used to underscore the unsettling effects of earthquakes. From the general agitation of nature (‘The Birds flew flutt’ring through the Air, / The Cows and Oxen low’d’) to the erasure of manmade delineations of space (‘the Stone-Fence the Country round, / Lies scatt’red o’er the Road’), the Cape Ann broadside depicts turbulence on multiple levels.46

The prominence of weathervanes in the Cape Ann woodcut reinforces the image’s focus on Boston. The undisputed maritime commercial centre of the north-eastern American colonies, Boston relied on the winds to keep its economy running. Because of this, Boston’s weathervanes and the lore which surround them remain to this day a pillar of the city’s popular history. In particular, the golden grasshopper weathervane of Faneuil Hall, considered by some to be ‘the most famous of all American weathervanes,’ features prominently in urban legends of the region.47 In 1742, Boston metalsmith Shem Drowne (1683-1774) installed this weathervane atop Faneuil Hall, Boston’s public market. Over time, the insect’s renown grew, bolstered by various instances of damage and theft. It is well recorded that one such episode occurred during the Cape Ann earthquake—John Winthrop describes how the ‘vane upon the public market-house … was thrown down,’ its spindle snapped in two.48 According to folklore historians, at one point in time, a person’s knowledge of Drowne’s grasshopper—or lack thereof—could determine if someone who claimed to be from Boston was telling the truth.49 In this way, the Faneuil Hall vane historically functioned as a shibboleth, an insider code so specific to the city of Boston that knowledge of it equated to membership within its citizenry. Even if this anecdote is more a tall tale than historical reality, it points to the longevity of weathervanes’ impact on Bostonian identity.

Additionally, the inclusion of weathervanes in the Cape Ann woodcut evokes several larger, overlapping frameworks for understanding seismic events. The prominence of the moon and stars taken together with the falling weathervane’s positioning creates a visual association with celestial portents, speaking simultaneously to Christian and Aristotelian conceptions of seismic activity. The woodcut’s careful shading suggests bright light shining down onto the people of Boston, laying bare the city’s sinful ways in the sight of God. Conversely, it may also allude to ancient understandings of comets and other meteoric phenomena, as Aristotle and philosophers of the Middle Ages had identified meteors and specific types of clouds as seismic harbingers.50Crucially, the image ties into weathervanes’ function as instruments that monitor and grant visibility to the wind, another invisible natural force. Still, this ability to demystify the natural world is exceeded by the persistently confounding and frightening nature of earthquakes. Winthrop describes how the toppled weathervane ‘had stood the most violent gusts of wind’ before the Cape Ann quake brought it down.51 Boston’s weathervanes allowed people to bring the wind, if not within their control, at least within their comprehension. However, the ultimate failure of these man-made instruments to withstand earthquakes demonstrates the futility of human attempts to grasp nature’s mysteries in their entirety.

Though all accounts confirm that Faneuil Hall’s grasshopper was the weathervane knocked to the ground in this instance, the Cape Ann woodcut clearly shows a church losing its weathervane. It is possible that its creators made an error in trying to keep up with the rapid pace of publication, however, due to the heavy-handed religious messaging that permeated discourse around the earthquake, it seems more likely that facts were manipulated to reinforce a theological interpretation of the event. Within a Christian frame of reference, an ecclesiastical building represents infinitely more than a mere physical structure.52 Therefore, a church’s broken weathervane not only signifies the literal physical destruction caused by the Cape Ann earthquake, but the symbolic damage it inflicted upon Boston’s societal and spiritual fabric. In this case, the Cape Ann woodcut seems to manipulate this symbolism to better align the earthquake’s narrative with a religious point of view.

LISBON AFTER THE FACT

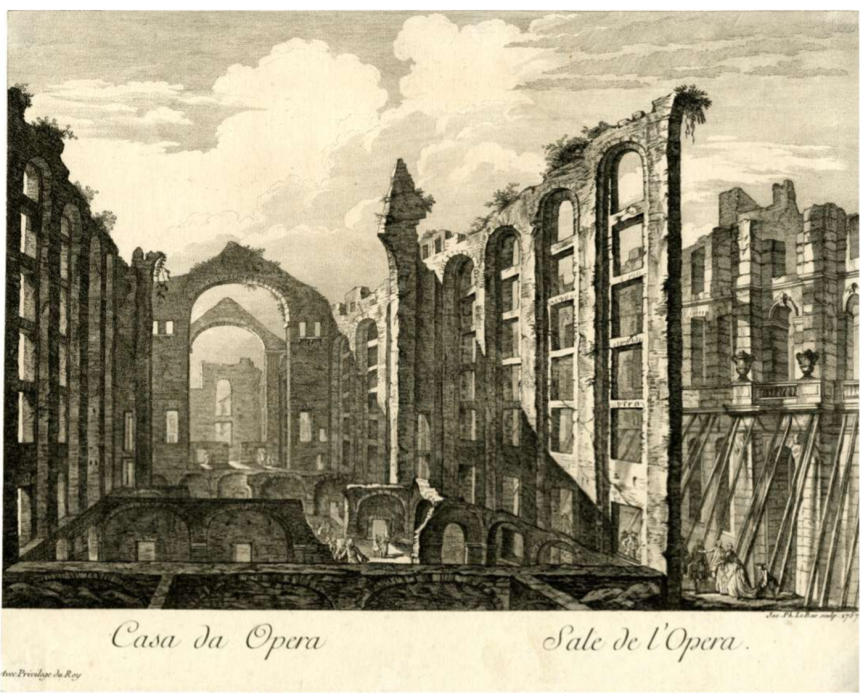

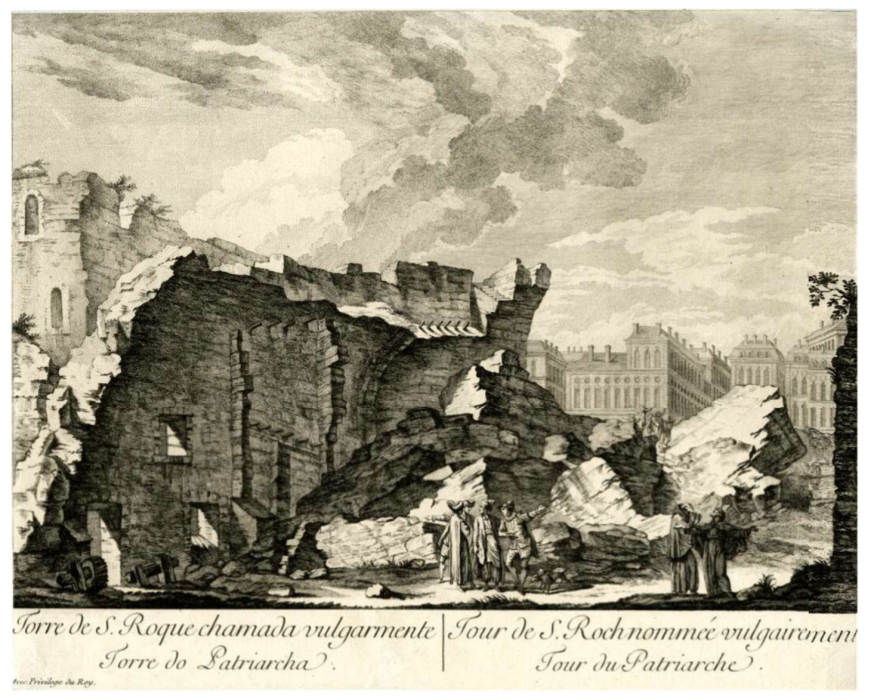

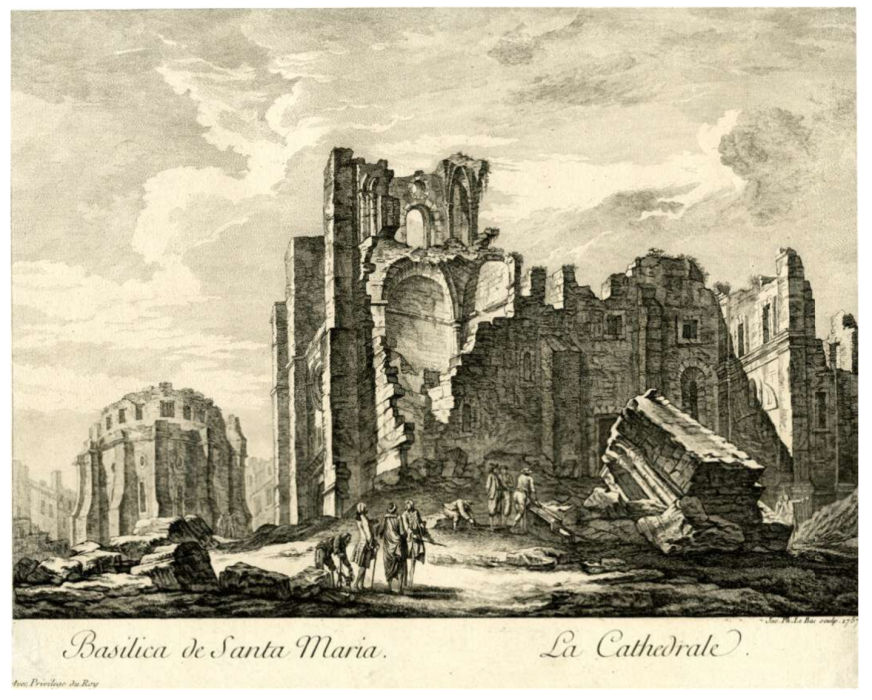

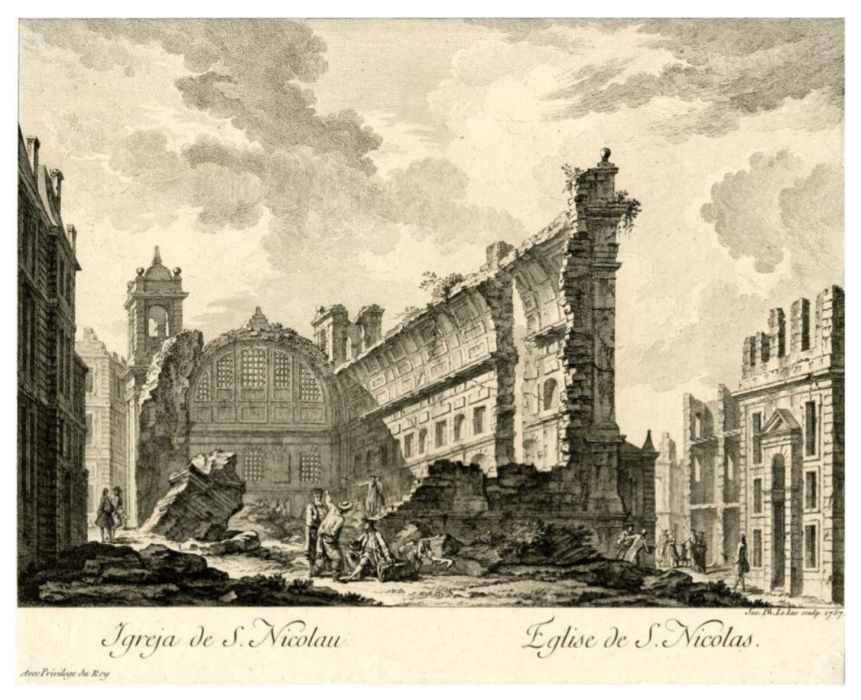

The final visualisation this article considers differs from the previous examples in several respects. In 1757, prominent French engraver Jacques- Philippe Le Bas (1707-1783) produced a series of prints showing the city of Lisbon after the earthquake of 1755. This sequence of six engravings features various ruined structures such as the city’s cathedral, opera house, and civic plaza (1757, Figs 3-6). While the Port Royal and Cape Ann images (Fig. 1, Fig. 2) depict earthquakes in progress and rely on accompanying texts to convey their narratives, Le Bas’ engravings leave viewers to contemplate an earthquake’s effects, featuring no textual information save for the engravings’ titles. These qualities manifest in the images’ respective print media. For example, the Port Royal and Cape Ann images, rendered in woodcut, could be set alongside type within a press and printed simultaneously, a quality which aided in the rapid dissemination of breaking news.53Conversely, Le Bas’ images, produced via a combination of engraving and etching, took significantly more time, effort, and skill to create.54 Therefore, the required delay in their production made them appropriate for expressing a delayed response to the Lisbon event. Offering a less didactic presentation of earthquake imagery, Le Bas leans into a naturalism that privileges the visual over the textual, a significant divergence from the bulk of seismic historiography.

Yet, while the choice to turn his attention to the earthquake’s aftermath allows Le Bas to sidestep many of the problems related to visualising an earthquake in progress, it also creates new challenges for him. Le Bas engraved other images of ruins throughout his career, drawing from source compositions of serene landscapes and calm pastoral scenes.55 However, the tone of his other views seems at odds with the violence implied by the ruins of Lisbon. I believe that this dissonance arises from Le Bas’ tapping into two visually similar but fundamentally different modes of viewing: the seismic and (what would later be codified as) the picturesque. Le Bas’ Lisbon resembles the work of Italian engraver Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778), who gained renown for his engravings of Italian architectural structures both real and imagined. Piranesi first found success with his ‘Antichità Romane de’ Tempi della Repubblica, e de’ primi imperatori’ (‘Roman Antiquities of the Time of the Republic and the First Emperors’) in 1748.56 In 1756, he published his most famous series, ‘Antichità Romane’ (‘Roman Antiquities’), an ambitious and expensive publication in four volumes. Piranesi’s popularity and professional accolades cemented the commercial viability of ruins as printed subject matter during this period: in 1757, the same year as Le Bas’ publication, the Society of Antiquaries in London elected Piranesi an honorary fellow.57 As Europeans flocked to Italy at the height of the Grand Tour’s popularity in the mid-eighteenth century, interest in Piranesi’s work no doubt caught Le Bas’ attention.58 By using Lisbon’s ruins as his subject, Le Bas could cater to a wider market, harnessing popular fascination with ruins conceptually and Lisbon specifically.

Le Bas’ prints rely on the same visual logic as Piranesi’s, using linear perspective to guide viewers through each image. Where the Port Royal and Cape Ann woodcuts compress entire narratives within their rectangular bounds, Le Bas’ compositional elements pull viewers through and beyond his images, implying that more lies over the horizon. In particular, Le Bas’ view of Lisbon’s opera house contains a diagonal wall leading towards a series of concentric arches, a device that draws viewers further into the ruins (1757, Fig. 3). This image, with its elevated, highly mediated vantage point, encourages a mode of viewing that English cleric, author, and artist William Gilpin (1724-1804) would begin to develop in the late 1760s as the picturesque. Gilpin writes that ‘Picturesque composition consists in uniting in one whole a variety of parts.’59 These parts (mountainous vistas, curving rivers, fallen trees) might naturally appear within a landscape, however, it was the artist’s role to select the best of these and combine them into an ideal image. As with the verification of a seismic event’s occurrence during this era, the picturesque was predicated on the act of human observation. At times, this piecemeal approach manifests in Piranesi’s work as well. Barbara Maria Stafford has remarked that, when certain aspects of a depicted structure remained obscured or unknown, ‘Piranesi responsibly sutured the certain to the conjectural, thereby allowing the seamed nature of his vision of the whole to show.’60 Thus, Le Bas and Piranesi both made use of a summative technique that over the following decades would become a core element of picturesque composition.

However, despite their shared subject matter and similar compositional approach, Piranesi and Le Bas’ ruins exist in fundamentally different contexts. Piranesi’s ruins bear centuries of overgrown foliage that soften the impact of whatever destructive forces they once experienced. Indeed, these structures had stood for millennia as the Roman people lived and worked amongst them, becoming integrated into everyday life (1757, Fig. 7). Though ruins served as a bittersweet reminder of human life’s transience, they also provided a natural and, in some ways, comforting conclusion to the life cycle of civilisations, showing the reabsorption of societal remnants into the natural world. Conversely, the relative lack of overgrowth in Le Bas’ Lisbon emphasises the recency of the city’s destruction—though, small tufts of vegetation atop broken walls do what they can to widen the gap between the earthquake and the present moment. Rather than offering the opportunity to reflect on the golden past, these images instead forced viewers to consider what the events of Lisbon meant for the future.

Further tonal discord appears within the images’ staffage. These stock figures, mostly well-dressed Europeans who gesture placidly at the sights before them, seem out of place given the horror Lisbon had endured. There are exceptions to this line of blandly curious characters, namely a group of monks looking to the heavens in despair, a distant band of panicked men and women coming over the horizon, (1757, Fig. 4) and a beggar hunched over a cane (1757, Fig. 5). The beggar could reference the hardships faced by survivors, while the monks might represent the spiritual anguish people felt towards the disaster.61 However, these are singular pictures of distress within scenes full of curiously indifferent onlookers. Read against the massive archive of material that documents not only the intensity but the specificity of people’s reactions to Lisbon, most of the inhabitants of Le Bas’ ruins come off as wooden, and indeed almost uncanny, as they fail to display the expected emotional response.

For the most part, Gilpin believed that the manmade stood as antithetical to the picturesque. Ruins were the exception to this rule, principally in the way they showed the manmade giving over to nature.62 Gilpin wrote that, to achieve picturesque beauty, ‘we must use the mallet, instead of the chisel: we must beat down one half of it, deface the other, and throw the mutilated members around in heaps. In short, from a smooth building we must turn it into a rough ruin.’63 Clearly, certain aspects of the picturesque required a surprising amount of violence to achieve. Of course, for Gilpin, this violent defacing remained completely theoretical, his interest in ruins relating solely to their appearance rather than the manner in which they came to be. Meanwhile, the harsh reality of Lisbon’s destruction makes the application of that same aesthetic exercise feel uneasy—though, David Marshall suggests that this kind of unease is already embedded into the premise of picturesque viewing. Marshall writes that ‘The picturesque represents a point of view that frames the world and turns nature into a series of living tableaux. It begins as an appreciation of natural beauty, but it ends by turning people into figures in a landscape or figures in a painting.’64 By calling upon the same visual mode that writers and artists invoked to package landscapes for clamouring tourists and art patrons to consume, Le Bas engenders conflicting sentiments in his viewers.

To make sense of these discrepancies, I turn to analysis relating to the ruination of another European capital, Paris. Between 1870 and 1871, Paris endured multiple violent conflicts that left much of the city in rubble. After a gruelling Prussian siege came the rise and subsequent brutal suppression of a popular governmental regime known as the Commune.65 Yet, even in the aftermath of events which cost tens of thousands their lives, eager spectators could not help but admire the city’s ruined aesthetic. Daryl Lee relates how ‘a minor culture industry sprang up on the smoldering ruins of the Commune and thrived as throngs of Parisians, provincials, and foreigners consumed the image of the ruined city.’66 The public desire to view and possess images of Paris in its fallen state helped distract from and dilute the radical, agitating politics of the Commune. The same type of morbid aestheticism comes through in the French title of Le Bas’ Lisbon images: ‘Recueil des plus belles ruines de Lisbonne’ (‘Collection of the most beautiful ruins of Lisbon’). Much in the same way that ‘the picturesque tenuously depoliticizes the ruins’ of post-Commune Paris, the picturesque mediations of Le Bas attempt to strip the ruins of Lisbon of their frightening theological and philosophical implications.67 Though the destruction of these two cities came about through different means, one via a natural disaster and the other via military and civil conflict, both cases saw major European cities reduced to rubble by violent forces. However, unlike the ruins of classical antiquity, people witnessed the destruction of these cities first-hand. Within a paradigm of modernity that placed Europe at the apex of Western progress, a mantle inherited from Ancient Greece and Rome, it was natural for Europeans to view classical ruins as a reinforcement of this timeline, tangible reminders that Greece and Rome are the past while Europe is the present.68 To have a modern Western city take on the appearance of ancient ruins in the blink of an eye completely disrupted this narrative, collapsing the progression that anchored Europe at the peak of modernity.

With his images of Lisbon, Le Bas offers his interpretation of an event which overnight shook the foundations of Western society. However, to reframe the Lisbon earthquake in a way that cushions the blow of its devastation, Le Bas’ engravings adopt a visual mode similar to William Gilpin’s concept of the picturesque. Rather than providing objective reportage, these engravings rely on tropes and tonalities associated with the leisurely consumption of landscape imagery. Yet, due to the inescapable violence and terror at the heart of the Lisbon narrative, these attempts backfire. In fact, Le Bas awakens contrasting visualities that exacerbate the unnatural qualities already embedded in picturesque viewing. Despite the visual similarities between his work and that of an artist like Piranesi, Le Bas’ ruins cannot escape their seismic context.

CONCLUSION

The images discussed in this article shed light on how inhabitants of the eighteenth-century Atlantic sphere visualised earthquakes in print media. For all that these documents fail to convey about the lived experience of earthquakes, they reveal a great deal about how people have historically grappled with mysteries earthly and spiritual that lay beyond their comprehension. In addition to documenting people’s responses to a historical event, these images provide a window into the epistemologies and thought processes that generated those responses. Working against the Atlantic Ocean’s temporal and spatial constraints, people strove to visualise the invisible phenomenon of earthquakes and in the process make sense of their world.

The study of earthquakes has historically remained confined within the bounds of distinct academic disciplines, resulting in parallel records which do not often overlap. This has caused information to fall through the cracks, as earthquakes pay no heed to the concept of manmade geographical boundaries, let alone disciplinary differentiations. As the field of Atlantic studies continues to rapidly develop, interdisciplinary collaboration presents the opportunity to remedy these oversights. One such collaborative opportunity can be found in the 2021 report issued by the Institut de Ciències del Mar. The map it provides, detailing the reach of the 1755 Lisbon tsunami, marks in red the locations from which there are no historical reports of oceanic disturbances on 1 November 1755 (2021, Fig. 8).69 However, the study’s seismic modelling indicates that these places, many of which line the Atlantic coast of North America, would have experienced tsunami events of varying intensity. This points to further avenues for archival research, for just as modern science can confirm historic eye-witness reports, it might also direct us towards yet-undiscovered historical records, artifacts, and even images. While these potentially unseen seismic events may have wanted for an observer in the past, by utilising an interdisciplinary lens, we might recover that which lies at the limits of vision.

![A Tsunami simulation for the Horseshoe Abyssal plain Thrust (HAT) over a regional bathymetric map showing maximum wave heights and tsunami travel time (30 min intervals), and illustrating the effects of bathymetric roughness in tsunami energy propagation. b. Close-up of the HAT tsunami simulation showing maximum wave heights and tsunami travel times (10 min intervals) highlighting the most affected areas along the SW Iberian and NW Moroccan margins… [Points in yellow indicate locations which reported oceanic disturbances on 1 November, 1755. Points in red do not possess correlating first-hand accounts of oceanic phenomena.] Diagram from Martínez-Loriente, Sara, Valentí Sallarès, & Eulàlia Gràcia, ‘The Horseshoe Abyssal plain Thrust could be the source of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and tsunami.’](https://courtauld.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/AC-image-8.png)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to Esther Chadwick, Lucy Chambers, Felix Jäger, Jonny Yarker, the Immediations editorial staff and external reviewers, and the Boston Public Library Special Collections for their assistance with this project.

Citations

[1] Malcolm Jack, ‘Destruction and Regeneration: Lisbon, 1755’ in The Lisbon Earthquake of 1755: Representations and Reactions, eds Theodore E. D. Braun and John B. Radner (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2005), 8-9.

[2] Alvaro S. Pereira, ‘The Opportunity of a Disaster: The Economic Impact of the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake,’ The Journal of Economic History 69, no. 2 (2009): 466-67.

[3] See Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Lettre de J.J. Rousseau citoyen de Genève, a Monsieur de Voltaire, concernant le poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne (Geneva: 1764); Voltaire, Poèmes sur le désastre de Lisbonne, et sur la loi naturelle, avec des préfaces, des notes, etc. (Geneva: Cramer, 1756).

[4] Jennifer L. Roberts, Transporting Visions: The Movement of Images in Early America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), 16.

[5] See Charles Gray, ‘An Account of the Agitation of the Sea at Antigua, Nov. 1, 1755. By Capt. Affleck of the Advice Man of War. Communicated by Charles Gray, Esq; F. R. S. in a Letter to William Watson, F. R. S,’ Philosophical Transactions (1683-1775) 49 (1755): 668–70; and Philip Tocque, Wandering Thoughts, Or Solitary Hours (London: Thomas Richardson and Son, 1846), 120-121.

[6] This is one of countless scientific studies which have examined historical seismic activity. For further studies on the 1755 Lisbon earthquake in particular, see the work of geophysicist Dr Maria Ana Baptista.

[7] Sara Martínez-Loriente, Valentí Sallarès, and Eulàlia Gràcia, ‘The Horseshoe Abyssal plain Thrust could be the source of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and tsunami,’ Communications Earth & Environment 2, no. 145 (2021): unpaginated.

[8] Rienk Vermij, Thinking on earthquakes in early modern Europe: firm beliefs on shaky ground(London: Routledge, 2021), 21.

[9] Susanne B. Keller, ‘Sections and Views: Visual Representation in Eighteenth-Century Earthquake Studies,’ The British Journal for the History of Science 31, no. 2 (1998): 130.

[10] Charles Daubeny, A Description of Active and Extinct Volcanos (London: W. Phillips, 1826), 356, quoted in Keller, ‘Sections and Views,’ 130.

[11] Derby Mercury XXIV, no. 44, 16 January – 23 January 1756, British Newspaper Archive, accessed January 23, 2024.

[12] Vermij, Thinking on earthquakes, 29.

[13] Charles D. James and Jan T. Kozak, ‘Representations of the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake,’ in The Lisbon Earthquake of 1755: Representations and Reactions, eds Theodore E. D. Braun and John B. Radner, (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2005), 28; John Michell, ‘LV. Conjectures concerning the cause, and observations upon the phænomena of earthquakes; particularly of that great earthquake of the first November, 1755, which proved so fatal to the city of Lisbon, and whose effects were felt as far as Africa and more or less throughout almost all Europe; by the Reverend John Michell, M. A. Fellow of Queen’s College, Cambridge,’ Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 51 (1759): 615.

[14] Kerrewin van Blanken, ‘Earthquake Observations in The Age Before Lisbon: Eyewitness Observation and Earthquake Philosophy in the Royal Society, 1665–1755,’ Notes and Records: The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science 76, no. 1 (22 July 2020): 32.

[15] Joseph Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), 3.

[16] Matthew Mulcahy, ‘The Port Royal Earthquake and the World of Wonders in Seventeenth-Century Jamaica,’ Early American Studies 6, no. 2 (2008) 397.

[17] Mulcahy, ‘Port Royal Earthquake,’ 401.

[18] ‘A true and perfect relation of that most sad and terrible earthquake, at Port-Royal in Jamaica, which happened on Tuesday the 7th. of June, 1692,’ woodcut broadside, [1692], Houghton Library, Harvard University, EB65 A100 B675b v.4. Emphasis in original.

[19] ‘A true and perfect relation.’ Emphasis in original.

[20] The broadside states: ‘Reader, Since the aforesaid dreadful Earthquake in Jamaica, one has been felt nearer to us.’ On 8 September of 1692, this nearer earthquake shook London and surrounding areas. Shocks were also felt in Dunkirk, the Hague, Paris, other locations in France, Germany, and the Netherlands, and by ships at sea. The broadside describes the effects of this later European quake, stating that ‘it caused the Earth to move like the Waves of the Sea,’ a simile that echoes the broadside’s pictorial elision between land and water.

[21] A 1694 London publication takes such an approach, evaluating the Port Royal earthquake alongside several earthquakes that had occurred in the Mediterranean. The volume features a version of the Port Royal broadside illustration as its frontispiece. However, its composition is flipped, likely because printing matrices will produce their images in reverse. Presumably, it was easier carve a block matching the broadside as it appeared rather than carve the image backwards. See R.B., The General History of Earthquakes being an Account of the most Remarkable and Tremendous Earthquakes that have Happened in Divers Parts of the World, from the Creation to this Time, as they are Recorded by Sacred and Common Authors, and Perticularly those Lately in Naples, Smyrna, Jamaica and Sicily : With a Description of the Famous Burning Mount, Ætna, in that Island, and Relation of the several Dreadful Conflagrations and Fiery Irruptions Thereof for Many Ages : Likewise the Natural and Material Causes of Earthquakes, with the Usual Signs and Prognosticks of their Approach, and the Consequents and Effects that have Followed several of them (London: Nath. Crouch, 1694).

[22] ‘A true and perfect relation.’ Emphasis in original.

[23] ‘A true and perfect relation.’ Emphasis in original.

[24] ‘A true and perfect relation.’

[25] Margaret J. M. Ezell, ‘Multimodal Literacies, Late Seventeenth-Century English Illustrated Broadsheets, and Graphic Narratives,’ Eighteenth-Century Studies 51, no. 3 (Spring, 2018): 358. For more on the acoustic qualities of the early modern world, see the work of Bruce R. Smith, Adam Fox, and Paula McDowell.

[26] Ezell, ‘Multimodal Literacies,’ 359.

[27] ‘Earthquake at Port Royal in Jamaica in 1692,’ The Gentleman’s Magazine vol. 55, no. 5 (November 1785): 880-81.

[28] Ben Hughes, Apocalypse 1692: Empire, Slavery, and the Great Port Royal Earthquake (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2017), 39.

[29] ‘A true and perfect relation.’

[30] ‘A true and perfect relation.’

[31] Hughes, Apocalypse 1692, 188.

[32] Julius S. Scott, The Common Wind (London and New York: Verso, 2018), 76.

[33] ‘A true and perfect relation.’

[34] Roberts, Transporting Visions, 21.

[35] John E. Ebel, ‘The Cape Ann, Massachusetts Earthquake of 1755: A 250th Anniversary Perspective,’ Seismological Research Letters 77, no. 1 (January/February 2006): 74.

[36] For a list of published responses to the Cape Ann earthquake, see Charles Edwin Clark, ‘The Literature of the New England Earthquake of 1755,’ The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 59, no. 3 (Third Quarter 1965): 295-305.

[37] Marguerite Carozzi, ‘Reaction of British Colonies in America to the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake: A Comparison to the European Response,’ Earth Sciences History 2, no. 1 (1983): 20.

[38] ‘Earthquakes improved: or Solemn warning to the world: by the tremendous earthquake which happen’d on Tuesday morning the 18th of November 1755, Between Four and Five O’clock’, woodcut broadside, [1755], Boston Public Library, pb.H.90.77.

[39] Whitney Barlow Robles, ‘Atlantic Disaster: Boston Responds to the Cape Ann Earthquake of 1755,’ The New England Quarterly 90, no. 1 (2017): 32.

[40] ‘Earthquakes improved.’

[41] Vermij, Thinking on earthquakes, 134.

[42] ‘Earthquakes improved.’ Emphasis in original.

[43] John Winthrop, ‘An Account of the Earthquake Felt in New England, and the Neighbouring Parts of America, on the 18th of November 1755. In a Letter to Tho. Birch, D.D. Secret. R. S. by Mr. Professor Winthrop, of Cambridge in New England,’ Philosophical Transactions (1683-1775) 50 (1757) 12.

[44] ‘Earthquakes improved.’

[45] ‘A true and perfect relation.’ Whether due to the passage of time or the author’s desire for dramatic effect, between 1692 and 1755 this story evolved from dogs eating the bodies of dead men to dogs eating men alive. Whatever the reason for this shift, this urban legend had obviously become established within the canon of Atlantic earthquake narratives.

[46] ‘Earthquakes improved.’

[47] Robert Bishop and Patricia Coblentz, A Gallery of American Weathervanes and Whirligigs (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1981), 14.

[48] Robles, Atlantic Disaster, 7; Winthrop, ‘Account of the Earthquake,’ 11.

[49] George F. Weston, Jr, ‘The Vanes of Boston,’ New York Folklore Quarterly vol. 13, Issue 4 (Winter 1957): 301.

[50] Vermij, Thinking on earthquakes, 167.

[51] Winthrop, ‘Account of the Earthquake,’ 11.

[52] Vermij, Thinking on earthquakes, 134.

[53] Bamber Gascoigne, How to Identify Prints, 2nd ed. (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004), 5a.

[54] Gascoigne, How to Identify Prints, 12b.

[55] For examples of other images of ruins engraved by Le Bas, see Julien-David Le Roy, Les ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce: Ouvrage divisé en deux parties, où l’on considere, dans la premiere, ces monuments du côté de l’ histoire; et dans la seconde, du côté de l’Architecture. Par M. Le Roy, Architecte, ancien Pensionnaire du Roi à Rome, & de l’Institut de Bologne (Paris: Chez H. L. Guerin & L. F. Delatour, rue Saint Jacques and Jean-Luc Nyon, Libraire, quai des Augustins; Amsterdam: Jean Neaulme, Libraire, 1758).

[56] Sarah Vowles, Piranesi drawings: visions of antiquity (London: Thames & Hudson and the British Museum, 2020), 12.

[57] Vowles, Piranesi drawings, 13.

[58] For more on the phenomenon of the Grand Tour, see Jeremy Black, Italy and the Grand Tour (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003); Andrew Wilton and Ilaria Bignamini eds, Grand Tour: The Lure of Italy in the Eighteenth Century (London: Tate Gallery, 1996).

[59] William Gilpin, Three Essays: on Picturesque Beauty; on Picturesque Travel; and on Sketching Landscape: to which is added a Poem, on Landscape Painting (London: R. Blamire, 1792), 19.

[60] Barbara Maria Stafford, Body Criticism: Imaging the Unseen in Enlightenment Art and Medicine (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991), 69.

[61] The panicked throng approaching in the distance remains a mystery, as the danger of the earthquake has long passed. From what could they be running?

[62] David S. Miall, ‘Representing the Picturesque: William Gilpin and the Laws of Nature,’ Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 12, no. 2 (Summer 2005): 82.

[63] Gilpin, Three Essays, 2: 5-8. Quoted in David Marshall, ‘The Problem of the Picturesque,’ Eighteenth-Century Studies 35, no. 3 (Spring 2002): 414.

[64] Marshall, ‘The Problem of the Picturesque,’ 415.

[65] For more on the history of the Paris Commune, see Peter Starr, Commemorating Trauma: The Paris Commune and Its Cultural Aftermath (New York: Fordham University Press, 2006).

[66] Daryl Lee, ‘The ambivalent picturesque of the Paris Commune ruins,’ Nineteenth-Century Prose 29, no. 2 (Fall 2002): 138.

[67] Lee, ‘The ambivalent picturesque.’

[68] David Irwin, Neoclassicism (London: Phaidon, 1997), 5.

[69] Martínez-Loriente et al, ‘Horseshoe Abyssal plain Thrust.’