In her introductory essay to the seminal exhibition The Body and the East, Zdenka Badovinac writes that ‘the presence of body is not a guarantee of truth, nor a reflection of the self, and it does not offer itself to the viewer as a one-way relationship … body art is counter-formalist, its meaning is not comprised within the limits of an autonomous and fixed object. Instead of a finished self-sufficient artefact we face the process of creation and, equally important, the process of perception.’1 It is perhaps this ambiguity in our encounter with the body in space which Badovinac describes that has produced such varied interpretations of Tibor Hajas’ performance Dark Flash (1978, Fig. 1). Read both as a means of social critique in the viewers’ initial passive response to Hajas’ unconscious body and as an individual pursuit of spiritual transcendence under Hungarian Communism, the work reveals the limit of bodily representation.2 Through Elaine Scarry’s idea of pain and the unmaking of material reality, this article explores Hajas’ use of masochism as a conduit of transcendence in Dark Flash, employing ideas from Béla Hamvas’ writings on Tibetan Buddhism and Hajas’ own literary explorations. I additionally consider the performance’s ephemeral nature and Hajas’ use of photography, both as a conceptual tool in his practice, and as a lasting document of what Kathy O’Dell sees as a contract between the audience and the artist.

Tibor Hajas’ radical corporeal explorations became a conduit for the artist to explore his interest in attaining an otherworldly spiritual experience. He was guided by ideas of Tibetan Buddhism presented in the books of Béla Hamvas, which circulated in the underground scene of the Hungarian avant-garde in the 1960s. Hajas used performance to control his body in ascetic enactments, stretching his endurance to its limits in events that sometimes—as is the case with Dark Flash—resulted in the artist falling into unconsciousness from self-inflicted pain and exhaustion. Beyond the use of pain for spiritual purposes, Hajas’ use of masochism also involves viewers in the action, as their response to the pain (or lack thereof) has ethical consequences. As such, masochistic pain demands the audience’s agency and challenges the relationship between the performer and the audience into forming a dynamic contract that may ‘remind viewers of their relation to real violence in the everyday world.’3

While little documentation remains from the performance of Dark Flash in 1978, a typed account is present in the De Appel archive in Amsterdam. My paper relies greatly on Michalina Sablik’s reading of this transcript in ‘Flash, Torture and Punk – Reconstruction of Performances by Tibor Hajas at Festivals in Poland in 1978.’4Sablik attempted to reconstruct Hajas’ performances Dark Flash and Hiroshima, both from 1978, through the remaining archival material of the events at De Appel and Galeria Labirynt.5 In my contextualisation of Hajas’ work, László Beke’s many essays on the artist have proven illuminating. Beke, being both an art historian and friend of Hajas, who himself witnessed many of the artist’s performances in action, has significantly contributed to understanding Hajas’ impact on Hungarian performance and the artist’s legacy following his early death in 1980.6

AUDIENCE CONTRACT

Dark Flash (Fig. 1) was enacted in 1978 at the International Art Meeting (IAM) in Warsaw, organised by the Polish Students’ Socialist Union (SZSP) and Henryk Gajewski, at the time director of the SZSP student club and art gallery.7 Sablik writes that Hajas was invited to participate in the meeting on the recommendation of the Polish artist duo Kwiekulik, who described Hajas’ work in sum as ‘a very good, shocking, precise performance’ that made ‘a great impression.’8 The event took place at Galerija Remont in Warsaw and featured a range of international performance artists, including Alison Knowles, Tomas Sikorsky, and Petr Štembera.9 Around-the-clock acts occurred at the meeting both inside and outside the gallery, such as Peter Bartoš’s Zoomedium, which involved the release of pigeons he brought with him from Czechoslovakia; a lecture on mail art held by the Mexican artist Ulisses Carrión; and a music gig by the British punk band The Raincoats.10 Hajas’ performance must have made an impact at the event, given that he was subsequently invited to the following year’s Works and Words exhibition at De Appel, Amsterdam, which showed work by Dutch and Eastern European performance artists. Many of the participants of the exhibition had originally met through “the IAM”. The event was initially planned to be open to anyone with the aim of ‘[giving] the public an impression of what “performance” is actually about.’11 However, when Polish authorities restricted public access to the meeting, the festival changed course.12 Instead, the emerging theme of the event came to be ‘And who are you?’, suggesting a shift to ideas about identity and points of interaction.13

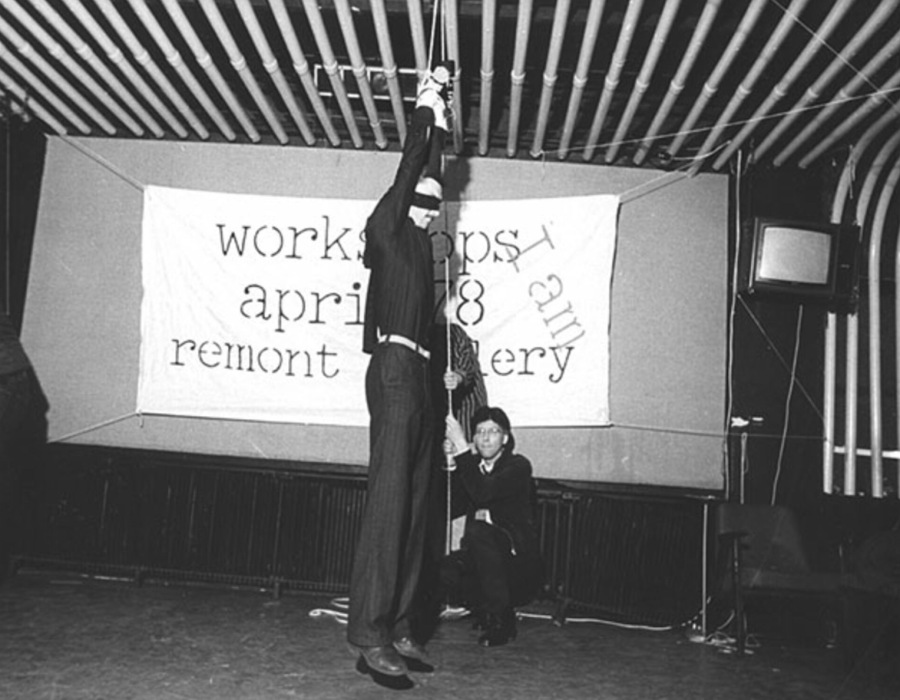

The performance of Dark Flash (Fig. 1) at the IAM took place in a dark room and opened with an audio statement pre-recorded by Hajas that played throughout the dim space. Sablik describes the recited text as ‘a stream of consciousness’ that gradually moved into darker themes including the description of fantastical beings; and, finally, the claim that Hajas ‘is a murderer’ (‘jest mordercą’).14 This opening audio set out an ominous narrative of power whose sinister content was emphasised further by the audience being cloaked in opaque darkness, as lack of sight gave way to sound and imagination. What followed was a sudden interruption of the dark by the sharp light of a magnesium flash, and, presumably, the sound of Hajas setting off a camera shutter. Here, as the audience discovered, the artist hung suspended from the ceiling, tied by his wrists with a camera in his hands. The song Oh Bondage by the short-lived British punk band X-Ray Spex now replaced the ominous audio. As the magnesium flash repeatedly went off, Hajas tried to time the intermittent bursts of light in an effort to capture the appearance of the audience in response to his performance with his shutter. Simultaneously, another camera was set up across the room to document the performance itself. Situated in intermittent darkness and light, the visual scene set up by Hajas was rhythmically made visible to the audience through the repeated flash. Finally, Hajas fainted from the drop in blood pressure caused by the physical restriction of his tied hands and suspended body. Although visibly unresponsive, it was not until members of the audience helped him down that the performance took its final step. While this audience interaction was not planned, such unofficial interventions and interactivity formed a central tool in the activities of the Hungarian neo-avant-garde, in which Hajas played a crucial part. Other notable activities of this period were Gábor Altorjay and Tamás Szentjóby’s action The Lunch, 1966, as well as experimental poetry the movement produced where, frequently, the ‘legibility of a text [needed] to be restored by the viewer’s intervention,’ its meaning dependent on active participation.15

Figure 1, held by De Appel in Amsterdam, remains the only known surviving image of Dark Flash from 1978, and shows Hajas hanging suspended from the ceiling in front of a festival banner reading ‘workshops / I am / april 1978 / remont gallery.’ Flash illuminates the dark space, creating a sharp contrast in tone and exposing all corners of the room. The black and white colours of the image emphasise the graphic forms of the composition, such as the repeated white lines of rods in the ceiling, which leads the eye to Hajas’ stretched body occupying the centre. The artist’s corporeal impassivity is stressed further by the two figures working in the back, crouching and bent in the action of either preparing the performance to start or moving Hajas’ unconscious body down from his ensnarement, consequently having made the conscious decision to end the performance. The destabilising slant of the photograph and the unsettling sense of looking up from below suggests the latter. Such an unnerving vantage point conveys an air of disarray which is further amplified through the many diagonals present in the image. What remains beyond the frames of the photograph and invisible to us contemporary viewers of the static image is the audience’s emotional reaction to the performance.

By performing an act of self-inflicted violence in front of an audience, Hajas entered what Kathy O’Dell argues to be a social contract between the artist and the viewers.16 According to O’Dell, this contract explores how our reactions to dangerous or unethical acts in the performance may reflect broader systems of power beyond the action itself.17 At the time of Hajas’ performance, Hungary had been in a state of what was coined ‘Goulash Communism’ for the past 20 years.18 Following the violent repression of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, the new government, run by former party secretary János Kádár, put a more liberal communism into action. Although eased market policies gave the illusion of freedom through economic reform, political and cultural censorship continued under the surface, as illustrated by cultural policy of the ‘three Ts: tiltott (forbidden), tűrt (tolerated) and támogatott (supported).’19 While many avant-garde artists did not make art that actively criticised the Hungarian state, their use of actionism and performance was regarded as anti-regime by the government because it strayed from the state-accepted definition of art, which adhered to realist painting and sculpture.20 The eccentric nature of mediums like performance and actionism, which could take any possible shape and be enacted anywhere at any time, was an ongoing issue for the state as their spontaneous nature could not be controlled or contained.

Hajas’ apolitical explorations through his ascetic performances and the artist’s focus on the individual experience rather than politics reflects the core ideas of Béla Hap’s ‘Silent Hungarian Underground Manifesto’ and the idea of the Hungarian underground as a cultural movement which neither accepts nor attacks the establishment.21 Members of the movement located themselves as an independent entity instead of an oppositional force to the regime, as they believed that directly criticising the state would only serve to legitimise its power.22 Klara Kemp-Welch situates Hap’s position within a larger framework of self-monitoring by dissidents in Central Europe at the time, stressing Győrgy Konrád’s influential notion of antipolitics: Kemp-Welch argues that the actions and performances as social spaces of ‘artistic encounters’ served as an answer to ‘Konrád’s question of, “How can we strengthen the horizontal human relationships of civil society against the vertical human relationships of military society?”’23 While Kemp-Welch emphasises art as means of forming civil relationships through the underground by bringing people together, I am interested in considering Konrád’s question in regards to O’Dell’s notion of the contract in performance art.24 I propose to examine the contract formed during Hajas’s enactment of Dark Flash as a bond between the audience and the artist, which challenges civil passivity in a militarised society.

However, given that Dark Flash took place in Warsaw in front of a small but international audience from both sides of the bloc divide and the Non-Aligned Movement, it is important to expand the analysis to reflect the performance’s international context. In Poland, the situation for artists was radically different to that in Hungary. This is evidenced by the fact that Galeria Remont, where the IAM festival took place, was state funded and operated as a student gallery inside the Warsaw Polytechnic; and many of the artists present, including Kwiekulik, relied on state funding and commissions to sustain themselves on the condition that their art remained uncritical of the state.25 Despite increased dissatisfaction due to rationing and government crackdowns on protests, ‘the possibility of working in the public sphere and having access to state subsidies was simply too significant a privilege to be jeopardised by the production of “undesirable” art,’ as Piotr Piotrowski suggests.26 In Czechoslovakia, the Warsaw Pact’s invasion in 1968 had increased public censorship on art in fear of another Soviet invasion, although some Czechoslovakian artists found spaces and contexts to exhibit and perform in Poland and abroad.27 While the 1975 Helsinki Accords promoted human rights and collaboration across the Eastern Bloc, the mid-1970s shift to neoliberalism, driven by the oil crisis and recession, reshaped global economies and societies, deepening inequalities by prioritising corporate power, privatisation, and reducing social protections.28 Such a multitude of socio-political settings suggests that the interpretations of Hajas’ work could vary widely among viewers. Yet the unified response by the audience to step in and react collectively not only demonstrated a moment of solidarity across nation-state borders but also embodied Konrád’s notion of fostering horizontal relationships as a counter to the global authoritarian structures of the Cold War era, employing Kemp-Welch’s rhetoric. While temporary, like the festival itself, this collaborative act and similar artist encounters formed ways to transcend national boundaries and establish networks of mutual support and resistance grounded in friendship and solidarity. The intimacy of such an act, given the small size of the audience, stresses both the individual’s responsibility against civil passivity and the necessity to act collectively with others in this aim.

Thus, while any autonomy or transcendence gained through Hajas’ act was fleeting, framed by the temporal confines of the performance, the momentary gesture was ‘burnt into [the audience’s] eyes,’ such that its lasting impact lay in its imprint on the viewers’ memory.29 This visceral display of collective civil resistance holds the potential to gain further, lasting meaning through the audience’s own encounters with militarised society across the Cold War divide.

PAIN AND TRANSCENDENCE

Dark Flash was Hajas’ lifelong exploration of ascetic spirituality inspired by Tibetan Buddhism, where pain and constraints on one’s self serve as a means of personal transcendence. In the book On the Other Side of the Intermediate State: The Art of Tibor Hajas and the Tibetan Mysteries, Béla Kelényi writes that Hajas repeatedly referenced and made use of the writings of Béla Hamvas, a twentieth-century Hungarian writer and scholar of metaphysics, modern art, and Eastern philosophy.30 Hamvas’ work had been banned in Hungary since 1948, when he was forced to retire from his position as senior librarian at the Budapest Public Library after being criticised by the Marxist philosopher Győrgy Lukács in his article ‘Hungarian Theories of Abstract Art,’ published in 1948.31 In his text, Lukács—at the time also a prominent member of the Hungarian Communist Party and the Academy of Sciences—claimed that ‘the support Hamvas gave to modern art resulted in an “objective” support of fascism,’ which contrasted with Lukács’ own aesthetic politics propagating Socialist Realism. Péter György and Gábor Pataki describe Lukács’ argument as ‘a prime example of the direct politicisation and instrumentalisation of aesthetic thought’ in his closed-minded judgment of Hamvas and other writers. Lukács, meanwhile, dismissed their work ‘as advocat[ing] … for petty bourgeois and decadent art’ and their ‘aesthetic considerations as ahistorical.’32 Despite his exile from the public sphere of publishing, Hamvas’ ideas subsequently found ground in the post-war Hungarian avant-garde, where they were distributed through informal systems. Maja Fowkes notes the appeal of Hamvas’ theories despite their public suppression:

‘Hamvas’ writings in samizdat editions circulated among the artists during the 1960s, finding fruitful ground in the younger generation, who were eager to learn more about myths and cosmic existence at a time when the countercultural craze for Eastern philosophies was as synchronous as the urge to stage happenings.’33

His writings on Tibetan Buddhism proved particularly influential, perhaps offering a spiritual escape from life under the Hungarian state apparatus in the aftermath of the violent repression of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Emese Kürti notes that the claim in Hamvas’ translation of The Tibetan Book of the Dead that ‘total freedom can be reached through the path leading to death and the state of death, which resists ingrained habits and is therefore the only state that can allow learning the true nature of the human being’ was especially impactful to the artist.34 As Béla Kelényi observes, however, the idea of Tibetan Buddhism presented in Hamvas’ collection, Tibetan Mysteries, was not only ‘in itself several times removed … from the original Tibetan text, but also from its English translation [by Walter Yeeling Evans-Wentz].’35 The practice of Milarepa, a Tibetan Siddha, whose ideas were made accessible to Hajas through Hamvas book, was a particular inspiration for the artist. Milarepa used performance in the form of song and dance as a spiritual enactment of self-inquisition and elimination of the ego.36 Milarepa was also known to practice chöd, a Buddhist meditative ritual, meaning ‘cut’ or ‘severance.’37 Aiming to ‘separate consciousness from the body’ to release the ego and achieve a temporary emptiness as a state of vigilance, Hajas repeatedly pursued chöd through his performances and writings.38

Hajas’ frequent use of painful ascetic practices in work and the incorporation of scriptures from Hamvas as well as his own writings evokes an idea of the performance as ritual. Here, the body and its environment are continuously used throughout planned events to produce sensory deprivation and liberation from one’s material existence. Márió Z. Nemes argues that what differentiates Hajas’ violent body art from the radical performances of the Viennese Actionists was the artist’s ‘monomaniacal interest in sacredness and transcendence’ as an artistic and spiritual pursuit of the work.39 There is an obsessive aspect to Hajas’ practice made visible in the corporeal expansions the artist seeks out to achieve transcendence, which are repeatedly enacted and explored through his work both as a poet and a performer. Considering the artist’s literary practice, Beke calls attention to the writer Istvan Őrkeny’s description of Hajas’ formal use of absence in his poetry in Don’t Give Up Anything (Ne Mondo le Semmiről), an anthology of poems published in 1974. Beke, quoting Őrkeny, writes that ‘when Hajas skips over something, he jolts the poem, indicating that a redundant, unknown, or perhaps even non-existent thing has been left out.’40 This attention to concept beyond words themselves—something left unsaid—was a method frequently employed by the Hungarian neo-avant-garde at the time: linguistic deconstructions through bodily and visual interventions sought to evade state censorship. Using absence as a mechanism of expression, artists worked across the realms of literature and art through scripts, actions, visual poems, and optical wordplay to make physical and conceptual space for language.41 Exploring the movement’s employment of language as a means of performance, Kürti suggests that the practice of the ‘Hungarian actionism can be described as expanded poetry, a linguistic performative transpiring in time and space, in which—in the spirit of Jacques Derrida’s interpretation—“gesture and speech have not yet been separated by the logic of representation.”’42 This relationship between ‘gesture and speech,’ body and script, and the immaterial concepts that remain unverbalised and abstracted in what is felt allowed an experience of reality unframed by the limits of language.43 Hajas’ use of writing and bodily actions also recalls the relationship between scripture and performances in religious practices where rituals are often pursued in relation to a text. Beyond Tibetan Buddhism, performances such as Vigil (1980) draw clear inspiration from Christian rituals and reinforce the concept of performance as a space for spiritual transcendence in Hajas’ practice, akin to how religious events may serve a similar purpose of enlightenment.44During this performance, Hajas was injected with sedatives by his assistant, János Vető, under alternating periods of light and darkness, thus sharing a pursuit of unconsciousness similar to Dark Flash. After the sedatives took effect, Hajas’ body was supposed to be electrocuted by Vető through a cord from the lights running through the puddle surrounding the artist’s body. However, Vető ultimately chose to disobey Hajas by disconnecting the power, much like how the audience of Dark Flash intervened to stop the performance after the artist fell unconscious. In the text accompanying the performance, Hajas explored the relationship between consciousness and matter, referencing Hamvas’ book, Tibetan Mysteries, and employing the motif of sleep.45He states that ‘my invulnerability is due to the total awareness of my fragility. It has come to such an extent that I am able to fall silent; I dare to fall asleep. I dare to grow dark, alone, amidst the lights going up-and I am able to endure the world that remains … without a scratch, untouched, without a master.’46 Here, sleep—a state of sensory deprivation akin to unconsciousness—presents a way to realise an experience of reality beyond the material constraints of everyday life, but also one that enhances that everyday reality once awake.

Furthermore, Hajas ascetically employs pain in his practice to transcend the material world and enter into another realm, to evoke a more authentic experience of reality and the self. As mentioned earlier, the artist’s engagement with Tibetan Buddhism involved a particular fascination with chöd—a practice producing a form of ego-death in ‘the enactment of separating the consciousness from the body.’47 On Chöd, Hajas’ performance of the same name (1979, Fig. 2), Fowkes writes that the ritual referenced functions as an exercise of ‘overcoming the illusion of the material world or maya that is represented through the skin of a body, which needs to be exposed to torment to get beyond the surface reality.’48 Similarly, Hajas’ interest in ascetic practices can also be seen in his employment of ego-death, a practice in Zen Buddhism that refers to a state of enlightenment achieved by dissolving the self, often produced through meditation, psychedelic substances, or rituals involving pain.49 In his text ‘Performance: The Sex- Appeal of Death (The Aesthetics of Damnation),’ Hajas outlines his interest in performance as a means of ego-death, where ‘the artist forces himself to be the object of his own art through performance, so that by becoming a work of art through the experience of death in the force field of sexuality, he gets excluded from the contingency of life, namely the hell of body and personality.’50

Thus, Hajas’ exploration and fascination with death emerges from the idea of its metaphorical transformative function as a separation and liberation from the self, much like his interest in sleep. As such, the motif of murder raised by Hajas in the audio of Dark Flash, where the artist says that ‘he is a murderer,’ verbally narrates the transformation that is completed through ego-death in the performance.51 Moreover, the idea of death is heightened through the element of public execution and the way that Hajas’ hands are tied with rope hanging from the ceiling, reminiscent of a noose. A method used to suffocate a victim until they lose consciousness and die, this violent allusion further amplifies the apparent danger in which the artist placed himself in front of the audience to reach such a state of transcendence.

Pain also provided a conduit for Hajas to temporarily distance himself from the world in its capacity as an intense sensation that isolates the subject from their immediate environment. Literary theorist Elaine Scarry writes on the disassociating power of pain: ‘Either it remains inarticulate or else the moment it first becomes articulate it silences all else: the moment language bodies forth the reality of pain, it makes all further statements and interpretations seem ludicrous and inappropriate, as hollow as the world content that disappears in the head of the person suffering.’52 Here, Scarry recounts how pain has the power to alienate the person experiencing it from reality, as pain ‘[silences] all else’ in its overwhelming dissociative sensation. Pain produces a deconstruction of material reality, partly because pain has ‘no object.’53 It is a feeling distinctly separate from ‘every other bodily and psychic event, by not having an object in the external world.’ Scarry further notes that this ‘“objectlessness” of pain, the complete absence of referential content, almost prevents it from being rendered in language: objectless, [pain] cannot be objectified in any form, material or verbal.’54This deconstruction may have produced a state of chöd as a separation from the immediate material reality, but one where one can return to later with greater insight. As such, it presents a means to achieve a temporary sensory emptiness as a state of vigilance about the world the artist inhabits. While the ritual of pain enacts a separation into the metaphysical, it simultaneously functions as a reminder of our corporeality, the vulnerability of our bodies, and our fleeting time on earth. The fitting choice of song, Oh Bondage by X-Ray Spex, highlights this objective. In a 2008 interview, the singer Poly Styrene explained that, despite the sexual implications of the lyrics, the song was really ‘about breaking free from the bondage of the material world.’55 Dark Flash reaches a climax of sensory deprivation when Hajas is interrupted by the audience, bringing him back to the material world.56 Such spontaneous intervention undermines the authoritarian power of the artist as the singular producer of the work, instead provoking the audience to act as dynamic participants in the performance.

FLASH AND PHOTOGRAPHY

Through the dramatic use of magnesium flash in producing a dichotomous state of light and darkness, the sensory deprivation that aids in attaining transcendence is heightened. We may note that the word ‘flash gun’ for camera flashes emerged from the forceful explosion produced by photographic flash powders with magnesium. It is a term that seemingly indicates the violence of photography and how light can enact a ‘temporary blindness,’ momentarily killing or removing human vision with its luminous force.57 Moreover, flash has the power to illuminate everything in a space, the unavoidable exposure produced by such an event itself being a form of violence.58 In a split second, the light unveiled not only Hajas, but also the audience, who became complicit in the artist’s pain as passive observers of the performance. When faced with bright light like the magnesium flash, the human eye creates a photogene, a retinal impression that remains in the vision for seconds after the light has ceased. The photogene becomes a form of corporeal memory of the performance that further emphasises the violence the audience has just witnessed, now resting in the uneasy realm of their mental recollection.59 There is a sense of duality in light as a mediator of sight and maker of images yet also a form of violence or erasure. It provides the means of vision while simultaneously producing an effect that blinds and obliterates information, an erasure similar in effect to the cover of darkness.60 Moreover, semantically, the word ‘enlightenment’—a term associated with the element of transcendence which stems from the word light—suggests a state of heightened knowledge, while darkness is often correlated to an oppressive ignorance, as is clear in phrases such as ‘being in the dark.’61 Hajas’ interest in the analogous and disparate effect of light and dark in their capacity to both reveal and conceal thus reflects a relationship between visible physical reality and a metaphysical state of transcendence. Further, the contradictory title of the work, Dark Flash, emphasises the duality between light and dark as a critical element of the work and implies darkness, likewise, as a source of light. Beke observes that ‘Hajas’ performances were as charged with darkness as death, sexuality, and suffering, and a momentarily illuminated image was, among other things, a metaphor for the fragility of life.’62 Life and death, creation and destruction, luminosity, and obscurity, all became interwoven concepts in the artist’s ascetic performances as concurrent means and hinderances to transcendence.63

Photography also presents a means of making and unmaking of the world, as is revealed through Hajas’ own writings on the medium. In the text ‘Photography as a Medium of Fine Art,’ the artist writes that ‘the one who makes himself in the image of the medium enters into more direct contact with reality.’64 To Hajas, photography served as a form of temporary suspension and a conduit of transcendence by shaping one’s relationships with the real.65 Continuing, he elaborates on the formation of identity through photography where one ‘is no longer determined by birth, name, or sex … biology has lost its unappealable right to divide; the dream invented about the totality of the personality gives way to the invention of the dream about the totality of existence. The new man can freely choose from the possible forms of existence, human skin, for the time being.’66 It is a statement reiterated by Amy Bryzgel, who argues that the photograph allowed Hajas ‘the possibility of constructing a different reality’: the image served as a ‘site of freedom’ beyond the repressive Hungarian regime, whose violence the artist had experienced first-hand following his imprisonment at nineteen years of age after publishing the political poem ‘Fascist Comrade’ in 1965.67 In works by Hajas such as Surface Torture (1978) and Flesh Painting (1978), both made in the same year as Dark Flash, the idea of self-transformation through the image is further manifested. Surface Torture demonstrates a literal manipulation of the surface of the image in order to disrupt the reading and construction of identity in the photograph. Meanwhile, the flattening effect of the black and white tones in Flesh Painting visually produces an illusion of the artist rubbing his own skin onto the wall, absorbing the black paint present on the surface. Through the image, Flesh Painting stages an act of the self in the process of escaping the confines of the body and merging with the environment, a visual transformation only made possible through the photographic documentation generated from the performance. Like Dark Flash, both works present a process of momentarily unmaking physical reality mediated by the photographic image and the camera as a ‘part of the act,’ like Bryzgel argues—not simply a means of documentation.68 Ultimately, however, the very presence of the photograph binds the metaphysical act to the material world, cementing the transient rays of light in physical form.

EPHEMERALITY

The ephemeral quality of performance art emphasises the fleeting nature of transcendence in Dark Flash. As Sablik notes, the ‘reconstruction [of a performance] always assumes incompleteness due to limited access to historical and factual knowledge.’69 This is also what has made it so hard to reconstruct this performance retrospectively, as the material (or lack thereof) presents a drastically different experience from seeing the original performance in the flesh. Taken from the perspective of the audience, the surviving photograph leaves us to speculate about what Hajas’ own images could have shown us—although it is equally possible that no photographs were made, given the difficult physical circumstances Hajas was in, tied up and perhaps unable to complete such an action. Frozen and framed by the confines of the image, the documentation of Hajas’ performance locks it into a single moment, a fraction of a second. Yet the existence of the photograph at De Appel emphasises both the temporary nature of the performance (as this fragmentary evidence is all we have left) and its occurrence at a specific time and place (its physical presence as an index of a historical event). Thus, the photograph also functions, O’Dell argues, as ‘a pseudolegal form of “proof” (a term relating photography to law) that an agreement took place,’ a document of the temporary contract enacted between Hajas and the audience.70 Like Bryzgel writes, describing the special relationship between photography and performance art in Central and Eastern Europe, ‘in the particular socio-political circumstances in which these artists were working … photography was a necessity for these ephemeral acts to both exist and survive’ beyond the moment itself.71 Jonah Westerman outlines performance’s paradoxical life between impermanence and perpetuation in the photograph through his text ‘Between Action and Image: Performance as “inframedium.”’72 Here, Westerman points out that photographs intensify the fleeting nature of performance by their ability to repeatedly ‘[present] it again and again to new audiences.’73 For Hajas, the image allows the artist’s moments of transcendence to escape the event’s confines and take on materiality as a tangible object capable of entering other rooms and contexts. This presence is itself a form of political resistance in making space for the individual pursuit of personal liberation and transcendence under the conditions of Hungarian communism that allowed no such expression.

In Hajas’s performance, masochistic pain became a personal pursuit while directly impacting the audience of Dark Flash, now faced with the ethical dilemma of remaining silent or responding to the danger in which the artist had put himself. The work did not aim to produce radical political change. Rather, like Hajas’s temporary transcendence, it sought to make the power structure between the viewer and militarised society visible through a momentary action and its inherent contract, revealing the individual’s potential to resist civil passivity. Describing the rise of performance art in Czechoslovakia following the Prague Spring and the protest-suicide of Jan Palach, Lara Weibgen writes that ‘to perform was not to change the universe, but to scar it with one’s body, to be an outpost of humanity in the midst of dehumanising forces—quite simply, to leave a mark.’74Hajas’ contract of pain formed such a mark, embedded in the memory of its audience and its lasting presence as a photographic document.

Citations

[1] Zdenka Badovinac, The Body and the East: From 1960s to the Present (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999), 10.

[2] Amelia Jones, ‘“Presence” in Absentia: Experiencing Performance as Documentation,’ Art Journal56, 4 (1997): 12.

[3] Kathy O’Dell, Contract with the Skin: Masochism, Performance Art, and the 1970s (Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1998), 5.

[4] Email correspondence with De Appel’s archival staff, October 2023.

[5] Michalina Sablik, ‘Błysk, Tortura i Punk: Rekonstrukcja Performance Tibora Hajasa Wykonanych na Festiwalach w Polsce w 1978 Roku,’ Sztuka i Dokumentacja 24 (2021): 81-82. In her text, Sablik also acknowledges the complications of conducting archival research on Hajas’ performances, as little material has survived, resulting in his practice remaining ‘terra incognita in art history.’ Yet, to exclude such works from scholarly attention for their fragmentary nature risks pushing them further into obscurity when they are already resting precariously ‘at the edge’ of art history for this very reason.

[6] László Beke, ‘The Hungarian Performance – after Tibor Hajas,’ in The Body and the East: From 1960s to the Present, ed. Zdenka Badovinac (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999), 103.

[7] Klara Kemp-Welch, ‘International Artists Meetings,’ in Networking the Bloc: Experimental Art in Eastern Europe 1965–1981, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2018), 358; De Appel, ‘I Am— Archive—de Appel Amsterdam,’ accessed 6 November 2023.

[8] Sablik, ‘Błysk, Tortura i Punk,’ 82.

[9] Kemp-Welch, ‘International Artists Meetings,’ 358; Marga van Mechelen, ‘Works and Words (1979) in the Shadow of IAM (1978),’ in L’Internationale: Post-War Avant-Gardes between 1957 and 1986, ed. Christian Höller (Zurich: JRP-Ringier, 2012), 317.

[10] Kemp-Welch, ‘International Artists Meetings,’ 360; De Appel, ‘I Am—Archive— de Appel Amsterdam.’

[11] Kemp-Welch, ‘International Artists Meetings,’ 361.

[12] van Mechelen, ‘Works and Words (1979) in the Shadow of IAM (1978),’317; De Appel, ‘I Am—Archive —de Appel Amsterdam.’

[13] van Mechelen, ‘Works and Words (1979) in the Shadow of IAM (1978),’ 317.

[14] Sablik, ‘Błysk, Tortura i Punk,’ 83. This and all translations are the author’s unless otherwise noted.

[15] Emese Kürti, ‘Poetry in Action: Language as a Performative Medium in the Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde,’ in Art in Hungary, 1956– 1980: Doublespeak and Beyond, ed. Edit Sasvári, Sándor Hornyik, and Hedvig Turai (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018), 293. In the happening, participants descended into a dark cellar where chaotic actions took place, including a pair of mice set free from a handbag, the artists vomiting, and various objects thrown between the artists and the audience. Ultimately, the participants could leave the event only after clearing the entrance blocked with even more objects. For more information, see ‘The Lunch (In Memoriam Batu Khan) (1968),’ in Parallel Chronologies, ed. Dóra Hegyi, Sándor Hornyik, and Zsuzsa László (Budapest: tranzit.hu, 2011), last accessed 11 November 2024.

[16] O’Dell, Contract with the Skin, 2.

[17] O’Dell, Contract with the Skin, 13.

[18] István Benczes, ‘From Goulash Communism to Goulash Populism: The Unwanted Legacy of Hungarian Reform Socialism,’ Post-Communist Economies 28, 2 (February 26, 2016): 146-166.

[19] Éva Forgács, ‘1956 in Hungary and the Concept of East European Art,’ Third Text 20, 2 (March 2006): 177–87; Bálint András Varga, ‘Two Essays on Contemporary Music,’ Music & Musical Performance: An International Journal 3, 3 (February 2023): 11.

[20] Magdalena Radomska, ‘Working in the Twice-mined Semantic Minefield,’ in Art in Hungary, 1956-1980: Doublespeak and Beyond, ed.Edit Sasvári, Sándor Hornyik, and Hedvig Turai (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018), 316.

[21] Klara Kemp-Welch, ‘Soft-Spoken Encounters: International Exchanges and the Hungarian “Underground,”’ in Art in Hungary, 1956-1980: Doublespeak and Beyond, ed.Edit Sasvári, Sándor Hornyik, and Hedvig Turai (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018), 273.

[22] Kemp-Welch, ‘Soft-Spoken Encounters,’ 273.

[23] Kemp-Welch, ‘Soft-Spoken Encounters,’ 273.

[24] Kemp-Welch, ‘Soft-Spoken Encounters,’ 273; O’Dell, Contract with the Skin, 13.

[25] Kemp-Welch, ‘The Students’ Club Circuit,’ in Networking the Bloc: Experimental Art in Eastern Europe 1965–1981, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2018), 315; Kwiekulik was censored after one of their images depicting the state’s coat of arms was paired next to an unfinished phallic shaped sculpture titled ‘Man-Dick’ in the exhibition catalogue, Seven Young Poles, in Malmö, Sweden, in 1975. Although the pair had no input in this publishing decision, it resulted in Kwiekulik being stripped of their passports and denied further financial support by the Polish authorities. For more information, see Kemp-Welch, ‘International Artists Meetings,’ 351.

[26] Piotr Piotrkowski, ‘The Neo-Avant-Garde and “Real Socialism” in the 1970s,’ in In the Shadow of Yalta: Art and the Avant-garde in Eastern Europe, 1945-1989, trans. Anna Brzyski (London: Reaktion Books, 2009), 286.

[27] Kemp-Welch, ‘The Students’ Club Circuit,’ 335.

[28] David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 12.

[29] Beke, ‘The Hungarian Performance – after Tibor Hajas,’ 105.

[30] Béla Kelényi, ‘“Do not let yourself be misguided, sir!” The Intermediate State: This Side and Beyond,’ in On the Other Side of the Intermediate State: The Art of Tibor Hajas and the Tibetan Mysteries, trans. Steven Kane, ed. Béla Kelényi and József Végh (Budapest: Ferenc Hopp Museum of Asiatic Arts, 2019), 10.

[31] György E. Szönyi, ‘The Philosophy of Wine: A Peculiar Chapter in the Esoteric Philosophy of Béla Hamvas (1897‒1968),’ in Studies on Western Esotericism in Central and Eastern Europe, ed. Nemanja Radulović and Karolina M. Hess (Szeged: JATE Press, 2019), 149; Arpad Szakolczai, ‘Moving beyond the Sophists,’ European Journal of Social Theory 8, 4 (November 2005): 417–433; Péter György and Gábor Pataki, ‘The European School and the Group of Abstract Artists,’ in A Reader in East-Central-European Modernism 1918-1956 (London: Courtauld Books Online, 2019), 404.

[32] György and Pataki, ‘The European School and the Group of Abstract Artists,’ 404.

[33] Maja Fowkes, ‘Off the Record: Performative Practices in the Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde and Their Resonances in Contemporary Art,’ Centropa: A Journal of Central European Architecture and Related Arts 14, 1 (January 2014), 56.

[34] Csaba Bekes, ‘The 1956 Hungarian Revolution and the Great Powers,’ Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 13, 2 (June 1997): 54-55; Kürti, ‘Poetry in Action: Language as a Performative Medium in the Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde,’ 307.

[35] Kelényi, ‘“Do not let yourself be misguided, sir!”,’ 12-13.

[36] József Végh, ‘From Milarepa to Buddhist Performance Art,’ in On the Other Side of the Intermediate State: The Art of Tibor Hajas and the Tibetan Mysteries, trans. Steven Kane, ed. Béla Kelényiand József Végh (Budapest: Ferenc Hopp Museum of Asiatic Arts, 2019), 43; Rachel Berghash and Katherine Jillson, ‘Milarepa and Demons: Aids to Spiritual and Psychological Growth,’ Journal of Religion and Health 40, 3 (2001): 380.

[37] Sarah Harding, ‘Chöd: A Tibetan Buddhist Practice,’ Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion, last accessed 25 March 2024.

[38] Harding, ‘Chöd: A Tibetan Buddhist Practice.’

[39] ‘Hajast a szakralitás és a transzcendencia iránti monomániás érdeklődése.’ Márió Z. Nemes, ‘Tűzhalál Magnéziumfénynél, Hajas Tibor: Kényszerleszállás,’ Balkon, 2005.

[40] László Beke, ‘Epilogue,’ in Hajas Tibor (1946-1980): Emlékkiállítás, trans. Steven Kane, ed. Béla Kelényi and József Végh (Budapest: Ernst Múzeum, 1997), 18.

[41] Beke, ‘Epilogue,’ 292.

[42] Beke, ‘Epilogue,’ 292.

[43] Beke, ‘Epilogue,’ 292.

[44] Tibor Hajas, ‘Vigil,’ in Hajas Tibor (1946- 1980): Emlékkiállítás, trans. Steven Kane, ed. Béla Kelényi and József Végh (Budapest: Ernst Múzeum, 1997), 14-16.

[45] Kelényi, ‘“Do not let yourself be misguided, sir!”,’ 14.

[46] Hajas, ‘Vigil,’ 16.

[47] Márió Z. Nemes, ‘Extended Directness: The Medial Strategies of Tibor Hajas in the Context of Chöd,’ in On the Other Side of the Intermediate State: The Art of Tibor Hajas and the Tibetan Mysteries, trans. Steven Kane, ed. Béla Kelényi and József Végh (Budapest: Ferenc Hopp Museum of Asiatic Arts, 2019), 26; Harding, ‘Chöd: A Tibetan Buddhist Practice.’

[48] Fowkes, ‘Off the Record: Performative Practices in the Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde and Their Resonances in Contemporary Art,’ 69.

[49] Roland Martin, ‘Ego death,’ Encyclopedia Britannica, last accessed 26 September 2023.

[50] István Erőss, ‘Eastern Europe: Artists in the Shadow of Politics: Hungary,’ in Body in the Landscape(Budapest: MAMŰ Society Cultural Association, 2022), 71.

[51] Sablik, ‘Błysk, Tortura i Punk,’ 83.

[52] Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 60.

[53] Scarry, The Body in Pain, 161.

[54] Scarry, The Body in Pain, 162.

[55] Poly Styrene, ‘Looking Back: ‘“Oh Bondage! Up Yours”’ and the Power of Poly Styrene,’ interview by Jessie Smith, Totally Wired Magazine, 4 February 2022.

[56] Beke, ‘The Hungarian Performance – after Tibor Hajas,’ 103.

[57] Kate Flint, ‘Blinded by the Light: The Violence of Flash Photography,’ Aeon, ed. Nigel Warbuton, 26 February 2018.

[58] Flint, ‘Blinded by the Light: The Violence of Flash Photography.’

[59] ‘Photogene,’ Oxford English Dictionary, July 2023.

[60] Flint, ‘Blinded by the Light: The Violence of Flash Photography.’

[61] Brian Duignan, ‘Enlightenment,’ Encyclopedia Britannica, last accessed 4 September 2023.

[62] László Beke and Luis Camnitzer, Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin (New York: Queens Museum of Art, 1999), 47.

[63] Beke, ‘The Hungarian Performance after Tibor Hajas,’ 105.

[64] Tibor Hajas, ‘Photography as a Medium of Fine Art,’ in Hajas Tibor (1946-1980): Emlékkiállítás, ed. Júlia Szabó (Budapest: Ernst Múzeum, 1997), 4-6.

[65] Hajas, ‘Photography as a Medium of Fine Art,’ 4.

[66] Hajas, ‘Photography as a Medium of Fine Art,’ 6.

[67] Amy Bryzgel, ‘Against Ephemerality: Performing for the Camera in Central and Eastern Europe,’ Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 27, 12 (2019): 12; Fowkes, ‘Off the Record: Performative Practices in the Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde and Their Resonances in Contemporary Art,’ 68.

[68] Bryzgel, ‘Against Ephemerality: Performing for the Camera in Central and Eastern Europe,’ 12.

[69] ‘Rekonstrukcja zawsze zakłada niekompletność ze względu na ograniczony dostęp do wiedzy historycznej i faktograficznej.’ Sablik, ‘Błysk, Tortura i Punk,’ 81.

[70] O’Dell, Contract with the Skin, 14.

[71] Bryzgel, ‘Against Ephemerality: Performing for the Camera in Central and Eastern Europe,’ 13.

[72] Westerman, ‘Between Action and Image: Performance as “Inframedium,”’ (Tate, 2015).

[73] Westerman, ‘Between Action and Image: Performance as “Inframedium.”’

[74] Lara Weibgen, ‘Performance as “Ethical Memento”: Art and Self‐Sacrifice in Communist Czechoslovakia,’ Third Text 23, 1 (January 2009),64.